- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Indian Agent Thomas Twiss, Man of Two Worlds

Indian Agent Thomas Twiss, Man of Two Worlds

Thomas S. Twiss had the kind of resume and political connections that made him ideal for appointment to a government position. Born in New York in 1802, he would be past 50 years old before he came to Deer Creek, near present Glenrock, Wyo., about 20 miles east of Casper, to act as government agent to the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota Sioux and other tribes of the upper North Platte River.

At the time, tribal nations were still strong. But White people were flooding into the West along the emigrant trails, the government had so far done a mediocre job meeting its obligations under a treaty with these tribes a few years earlier, tensions were growing in all directions and the threat of war was constant.

Yet Twiss thrived, for a while, in that world; in his job as Indian agent he seems to have been the kind of bureaucrat who would take actions he thought necessary, rather than waiting to ask permission. In the West he had an Oglala Lakota wife and family, while staying in touch with his first wife and family in the East. These and other factors made him friends and enemies on both sides of the ever-growing cultural divide.

Early life

Thomas Twiss graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point second in his class in 1826. Commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, he taught mathematics at West Point and worked on the construction of Fort Adams in Newport, R.I.

Resigning from the military in 1829, he spent the next 17 years teaching and administering at Georgia schools in Sparta and Augusta, and finally at South Carolina College in Charleston. At the latter, he became known as a stern disciplinarian while teaching and supervising building construction on the campus. In his household with his invalid wife and three daughters, he also kept an enslaved woman and he managed other enslaved people while working on campus projects.

Twiss resigned from the college in 1846 to become superintendent of South Carolina iron producer Nesbitt Manufacturing Company. This establishment also operated with slave labor, even though Twiss later emphasized to a daughter that he was strongly opposed to slavery. In 1850 he and his family moved to their farm in Wynantskill, in upstate New York near Troy and Albany, not far from where he grew up. Twiss became the resident and consulting engineer for the Buffalo and New York City Rail Road Company.

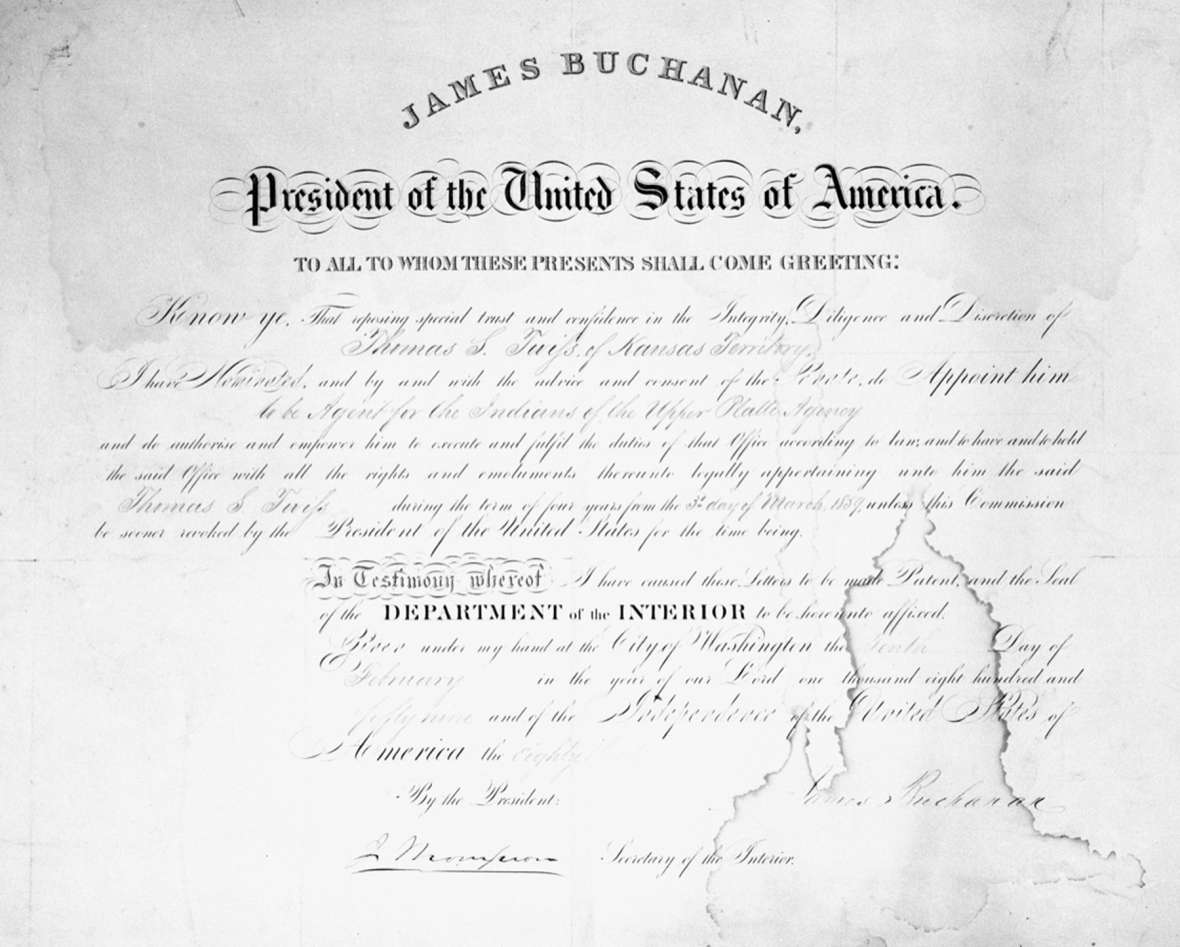

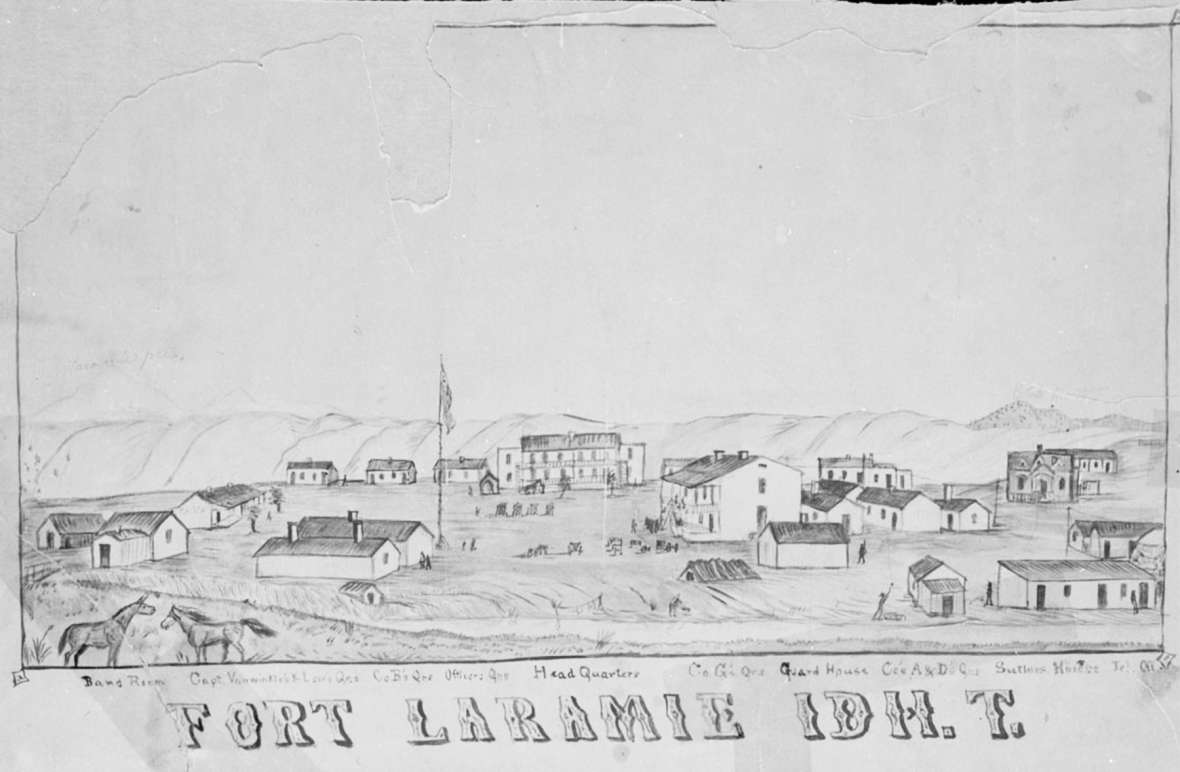

During his time at West Point, Twiss had tutored younger cadets. In 1855, one of them, Jefferson Davis, later to become president of the Confederacy, was serving as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce. In March, these connections led the president to nominate Twiss to serve as agent of the Upper Platte in the Office of Indian Affairs. With the title of major commonly assigned to Indian agents, even though they were civilians, Twiss was sworn in and, on Aug.10, 1855, arrived at Fort Laramie. His life would never be the same.

Friction with the Army and the traders

Soon after taking office, Twiss reported to the secretary of the Interior that he could not find any hostile Indians within the agency. This was despite the fact that General William Harney’s expedition to punish the Sioux for killing Lt. William Grattan and his command on Aug. 19, 1854, created a general state of war. The conflict culminated in destruction of the Brule Lakota village of Little Thunder at Ash Hollow in western Nebraska Territory in early September 1855.

Twiss identified and isolated peaceful villages south of the South Platte and Laramie Rivers, claimed that they desired to have a farmer and a blacksmith assigned to them, held a council with headmen of the Oglala Lakota and by early October was convinced that the Brulés and Oglalas had no part in conflicts during the past year. He thought it important to isolate the tribes away from Fort Laramie, and advised that the establishment of missions and schools be a priority.

Agent Twiss pursued his duties with energy and dedication while forming strong opinions about Fort Laramie’s military and civilian residents including traders and mountaineers—a word that meant former trappers and mountain men, often with Native families. He came into conflict with Fort Laramie commander William Hoffman and with General Harney, who had led the attack at Ash Hollow.

Twiss opposed Harney leading treaty negotiations—normally the job of the Indian Bureau—and Harney ordered him arrested and removed from office. But the general did not have authority over Twiss. The secretary of Interior endorsed him continuing in office and determining actions related to treaties and trade.

Twiss, for his part, quickly concluded that traders, especially Seth Ward at Fort Laramie, were a significant source of corruption in the conduct of Indian affairs. He revoked Ward’s trading permit and established strict rules for trade with the tribes. Before long, the traders began to assault the agent’s integrity.

Twiss traveled east to visit his family and conduct official business in 1856. By June of that year, when he checked into the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., charges had been assembled against him. His accusers charged that he had traded annuity goods to the Indians in exchange for buffalo hides. (Annuity goods were the tribes’ annual payments from the government as part of the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851.) And two interpreters for the Indian agency specifically testified that late in 1855 Twiss had exchanged cloth, blankets, knives, kettles, sugar, coffee and horses for a young Oglala woman.

A new wife—and some proposals

But, apparently satisfied with his defense, the commissioner of Indian affairs cleared Twiss to return to his duties. Despite accusations of impropriety, it is clear that in late 1855, Thomas Twiss had married a member of the Spleen Band of the Oglala Lakota. She was the daughter of Standing Elk, named Wanikiyewin, meaning “Savior of her People.” Generally, she was called Mary. The couple’s first of seven children would soon be born.

Despite political troubles, questions about his honesty, and the opposition of white traders and mountaineers, 1856 and several years afterward were relatively peaceful on the upper North Platte with much credit going to Thomas Twiss. He organized a small akicita police force of Lakota warriors to help keep things in order during the issue of annuity goods, to counter depredations against emigrants and to help curb intertribal warfare.

He made proposals to keep the tribes away from emigrant routes, to set up new agencies with farms and trading posts and to encourage traders who married into the tribes to help teach farming to the Indians. For the Arapaho, Lakota and Cheyenne, he meant to give them the means for subsistence so they would abandon traditions of traveling widely to hunt. He also intended that missionaries should be encouraged to help teach new ways to them.

In short, he believed that the press of emigration and settlement would spell the end for the tribes unless the government made changes. In the decades to come, many of these proposals—Indian police, the teaching of farming, foodstuffs that would replace wild meat, and missionaries—would all, for good or bad, become parts of the Indian reservation systems on the northern plains.

The move to Deer Creek

To bolster his claims about the dangers to the tribes of the growing influx of Euro-Americans, Twiss reported to the commissioner of Indian affairs that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—were developing a large mail station at Deer Creek, 100 miles west of Fort Laramie. It was to be part of a new West-wide shipping and freight network, the Brigham Young Express or BYX . The land surveyed on Deer Creek was meant, Twiss said, to accommodate a population of 500 with 200 acres under the plow to grow produce.

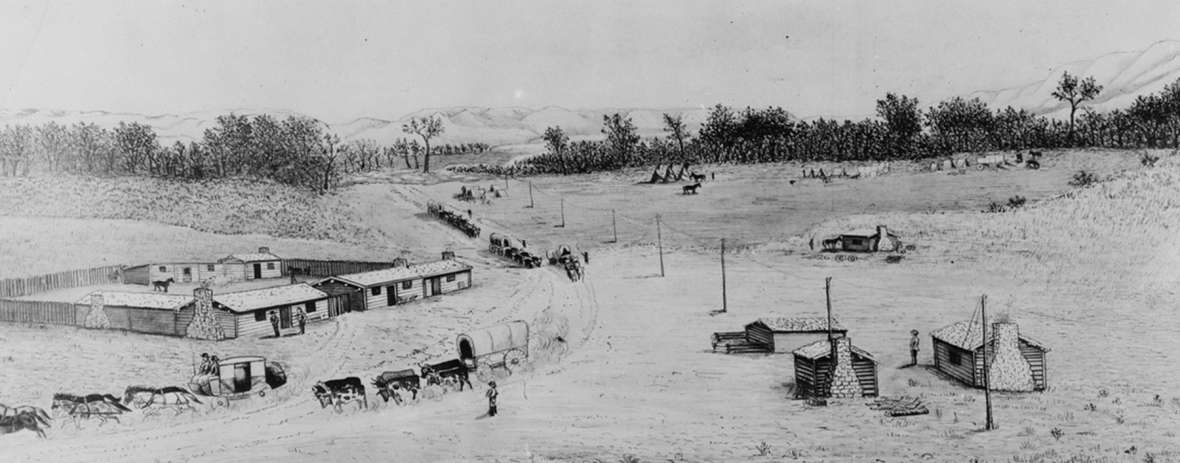

Twiss asked for authority to evict the Mormons. But soon, the so-called war between the United States and the Mormons forced the Mormons to abandon the site with some buildings built and others still under construction. By the late summer of 1857, Thomas Twiss had moved his quarters and the Upper Platte Agency from Fort Laramie to Deer Creek. His interpreter was trader Joseph Bissonette, who also set up trading operations with a store in one of the buildings and ultimately became postmaster and the stage station operator. Bissonette by then had been operating in that country for at least 15 years, The community began to grow with Bissonette’s extended Sioux family and that of another trader, John Richard.

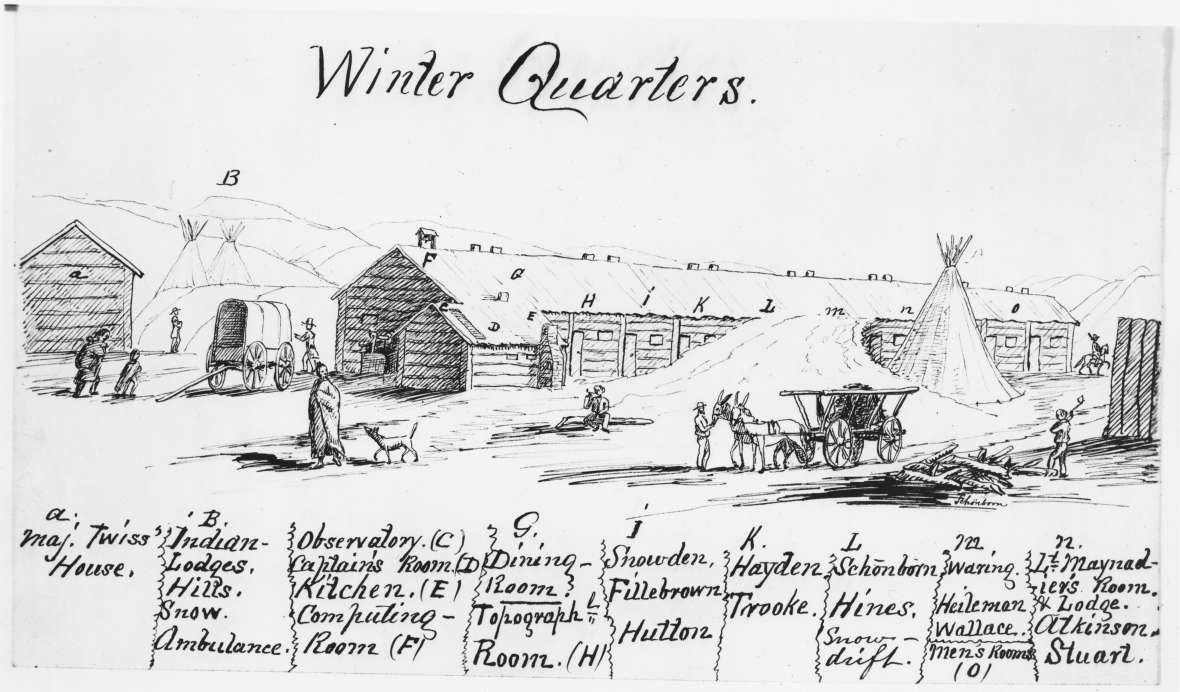

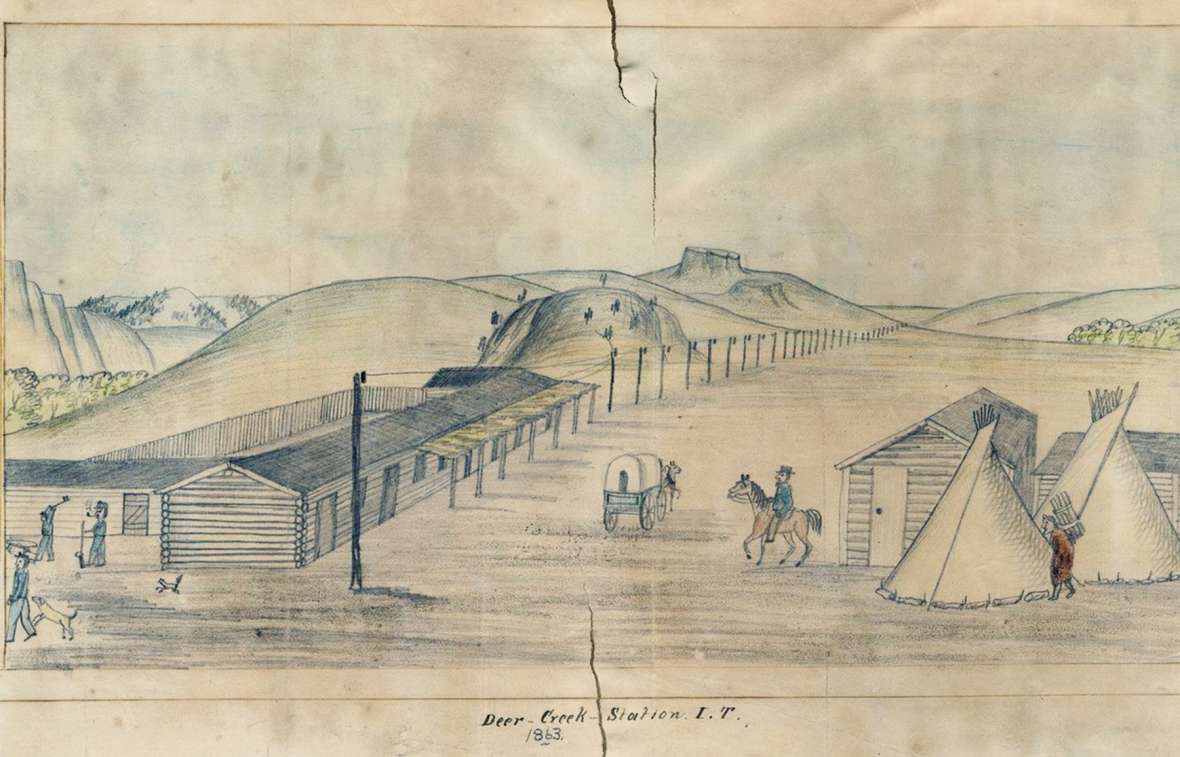

By the fall of 1859, Deer Creek thrived as a crossroads of humanity with emigrants passing through and Cheyenne, Lakota and Arapaho people camping nearby to receive annuity goods. That fall, a small colony of German-speaking Lutheran missionaries took up temporary quarters in one of the buildings. Soon, a government survey expedition led by Captain William F. Raynolds moved in to spend the winter.

Maj. Twiss did much to provide for the needs and comforts of these newcomers, while continuing with his duties as agent. With spring, the survey party departed and the missionaries moved north to set up a mission on the Powder River. It was soon abandoned after a Sioux party killed of one of the missionaries, however. A year later, the Lutherans built a mission of their own at Deer Creek.

The Rev. Karl Krebs provides us with one description of the major at this time. He noted Twiss’s Lakota wife and two children and said that “the major wore long hair and had braided it with two braids just like the Indians. He owned much cattle, horses, and chickens. He also had a number of Indians who hunted for him, and received their board and clothes from him. He also had white people working for him who took care of his herds. He was a kind of government in himself and led a commodious life.” The operation sounds almost feudal, with a lord of the manor at the top, bound to his retainers by networks of mutual protection and support.

Complaints, and a resignation

In 1860, an Overland stagecoach pulled in at Deer Creek and a British travel writer, Sir Richard Burton, stepped down. Burton was on his way to interview Brigham Young in what he called “The Mecca of the Mormons,” Salt Lake City. Burton’s book, The City of the Saints and Across the Rocky Mountains to California, includes an interesting description of Twiss.

Along the way, Burton had met Chief Little Thunder—the same Little Thunder whose Lakota village had been destroyed by Harney’s troops a few years before—headed in the opposite direction toward Fort Laramie. The chief, Burton recorded, intended to present a complaint to military authorities that Twiss took annuity goods intended for the tribe, the flamboyant Burton noting that a pet bear living at Deer Creek received more sugar than the Indians themselves. Official complaints were filed, but Twiss again successfully defended himself against the suggestion that his wife’s tribe received more goods than the Cheyenne did, and that annuity goods often ended up on the shelves of Bissonette’s store.

But it was not because of these complaints that Thomas Twiss resigned his position with the Upper Platte Indian Agency. The administration of President Buchanan had ended. Abraham Lincoln appointed a new agent, who shortly moved the agency back nearer to Fort Laramie. Twiss made his final reports and accounting in early 1861. He remained known as the major and occupied a ranch several miles from the Deer Creek station. He raised stock and more children.

In the fall of 1861, Twiss became acquainted with a young telegraph operator stationed at Bissonette’s store. Oscar Collister observed that Twiss had “adopted the habits of the country,” living the life of a mountaineer, a class of individuals he originally had condemned. Twiss loved to play chess and the two of them became friends, often sharing news about military campaigns on Civil War battlefields to the east. Collister also leaves us with a fascinating account of a Bissonette employee playing the violin while Twiss and the others taught the Indian women to dance “the old fashioned quadrilles, and they became quite efficient.”

Departure

Beginning in 1862, the government pulled regular troops out of the West to fight the Civil War in the East, and the tribes, in that power vacuum, stepped up their raids along the emigrant trails. In 1862, volunteer regiments from Kansas and Ohio were filling the void, but Twiss briefly abandoned his ranch when Indian attacks threatened his security. He returned to find his ranch in disarray, with windows smashed and trunks and boxes broken open, but settled back down to being something of a peacekeeper amid the troubles, as he had so many connections on both sides of the Indian-white divide.

His relationship with the Lutheran missionaries soured, however. They came to distrust him, Rev. Karl Krebs noting that “since old man M. Twiss was so sly, his help did not amount to much.” Conflicts with the Lutherans also arose over the whiskey trade conducted by Bissonette and others. Twiss did little to address this problem. And there was also trouble at home; Mary took their youngest child and left. She returned, but times were clearly stressful.

Finally, in the fall of 1864, serious altercations with emigrants, the military and the Lakotas and Cheyennes caused Twiss to leave Deer Creek for the last time. He appeared at Fort Laramie with his Indian family that year and was described years later, from memory, by Capt. Eugene Fitch Ware. Ware recalled the arrival at the sutler’s store of finely dressed Lakota women “with an old gentleman whose hair, long, white and curly, hung down over his shoulders, and down his back. He had a very venerable white beard and moustache. . . . He was dressed thoroughly as an Indian. He wore nothing on his head, and had on a pair of beaded moccasins. He sat on one of the benches in front of the sutler store, having in his hand a cane, staff fashion, about six feet long.” He then engaged officers in a deep analytical discussion of General Grant’s tactics at Vicksburg, comparing them with Napoleon’s tactics at the Battle of Borodino.

Thomas Twiss visited his New York family almost every year from 1856 at least until 1860. He had conveyed his 80-acre New York farm to his mother-in-law in about 1855. The property then became that of his wife Elizabeth S. Twiss, who had been an educator but for most of her adult life suffered from mental and physical illness. She died in 1866 and willed her farm and estate to her daughter Mary Twiss. Clearly, Thomas Twiss, in his later years, was most devoted to his Indian family.

It is suggested that they were living in Nebraska City in eastern Nebraska Territory in 1865 although others claim the Twisses went north and west into the Powder River country to live among increasingly combative Sioux relatives. In 1870 they were in Rulo, also in eastern Nebraska, where the major intended to plant a fruit orchard. He died in poverty there in January 1871 and a year later was buried next to his first wife near his home in Wynantskill, N.Y.

The Legacies of Thomas Twiss

Twiss was a flawed, complicated man, but an accomplished one. In the decade after his death, crossing cultural divides like the ones he crossed so often became far more difficult for most Americans. But his life reminds us of the time in North America before the Civil War, when crossing those divides, and acting effectively on both sides of them, had been for many people—Indian, white and mixed-race, alike—routine.

Evidence of his life is found in the written record and demonstrated through time by the legacies of what he collected and the continuation of his family to today. All of these legacies demonstrate the persistence of Native cultures and the importance of inter-relationships and extended families formed by Native women and white newcomers.

Important to the Twiss legacy is an exceptional collection of more than 70 Lakota, Cheyenne and other objects now at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. The objects represent the flowering of Plains cultures prior to the destruction they faced in the decades after Twiss collected them in the vicinity of Fort Laramie and Deer Creek between 1855 and about 1865.

A cryptic note accompanies the collection, stating that “these Indian relics were sent by Major Twiss to his wife and daughters.” A woman named Daisy Barnett acquired the collection, presumably from Twiss’s New York family, and in 1918 sold it to the Museum of the American Indian in New York City using funds from a patron. The accompanying photo gallery provides a sampling of the collection that also includes weapons, containers, leggings, horse equipment and headdresses.

The Twiss Family

The Oglala Lakota gave Mary Standing Elk the name Wanikiyewin, meaning “Savior of her People,” and the tribe benefited from her influence upon her husband, Thomas Twiss. When the major died, one of Twiss’s New York relatives visited Nebraska and took young William Twiss back east. He soon returned and readopted Lakota ways with his brothers. Mary Standing Elk moved with her seven Twiss children to Fort Robinson, Neb., and they are listed in the 1875 census record of the Crazy Horse Surrender Ledger. Thereafter they settled with other Oglala Lakotas on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

In 1876 Charles and Bridge (James) Twiss served as scouts in General George Crook’s campaigns against the Sioux. Three years later the youngest son, Frank, was enrolled at the Indian School in Carlisle, Pa. Charles again served as a scout at the time of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre and sadly, his brother William Twiss was among those tasked with burying the Lakota men, women and children killed at Wounded Knee. Despite the fact that Thomas Twiss predicted the extinction of the Lakota, the descendants of Thomas Twiss and Mary Standing Elk are still an important part of the survival and persistence of Oglala life today.

Editors’ note: This article was funded in part by Rocky Mountain Conservancy, a nonprofit Cooperating Association based in Estes Park, Colo., through book store sales at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper, Wyo. We offer our special thanks.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Moldenhauer, Roger, ed., "The Doederlein Diary, 17 May 1859-February 1860," Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly, Fall 1978.

- United States Government Printing Office. Raynolds, Willliam F. Report on the Exploration of the Yellowstone River,1868.

- United States Government Printing Office. Office of Indian Affairs, Annual report of the Commissioner of Indian affairs, for the years 1855-1861.

- United States Congress, 35th Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives. “The Utah Expedition.” Ex. Doc. No. 71. 189-197.

- “A Mormon Usurpation,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) Sept. 23, 1857.

- “The Late Thomas S. Twiss,” Times (Troy, N.Y.) March 9, 1872, accessed Jan. 11, 2022 at https://amertribes.proboards.com/thread/261/agent-thomas-twiss

- “Standing Elk,” accessed May 6, 2022 at https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~mikestevens/genealogy/2010-p/p302.htm.

Secondary Sources

- Bennett, Colin. “Compacts and Compromises: Thomas S. Twiss and West Point Influence in the Antebellum South Carolina College,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 109, no. 1 (January 2008): 7-37.

- Bryans, Bill. Deer Creek: Frontiers Crossroads in Pre-Territorial Wyoming. Glenrock: Glenrock Historical Commission, 1990.

- Burton, Sir Richard F. The City of the Saints: Among the Mormons and Across the Rocky Mountains to California. Santa Barbara, Calif., The Narrative Press, 2003.

- Collister, Oscar. "Life of Oscar Collister." Annals of Wyoming 7, no. 1 (July 1930): 343-361.

- Hill, Burton S. “Thomas S. Twiss, Indian Agent,” Great Plains Journal 6, no. 2, (Spring 1967).

- Hoopes, Alban W. "Thomas S. Twiss, Indian Agent on the Upper Platte, 1855-1861," Mississippi Valley Historical Review 20, no. 3 (December 1933): 353-364.

- Hyde, George E., Spotted Tail’s Folk: A History of the Brule Sioux. 1961, Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Mackinnon, William P. “And the War Came: James Buchanan, The Utah Expedition, and the Decision to Intervene.” Utah Historical Quarterly 76, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 22-37.

- Paul, R. Eli. Blue Water Creek and the First Sioux War, 1854-1856. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

- Shores, Leslie. ”A Look Into the Life of Thomas Twiss, First Indian Agent at Fort Laramie,” Annals of Wyoming 77, no. 1 (Winter 2005): 2-12.

- Unrau, William E. “The Civilian as Indian Agent: Villain or Victim?” Western Historical Quarterly 3, no. 4 (October 1972): 405-420.

- Ware, Eugene F. The Indian War of 1864. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1960, 210-211.

Illustrations

- The image of Caspar Collins’s 1862 watercolor of Deer Creek Station is from the Denver Public Library. Used with permission and thanks.

- The drawing of Fort Laramie, the drawing of winter quarters on Deer Creek, 1859-60, and the other drawings of Deer Creek Station are from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- All the rest of the images are from the collections at the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Used with permission and thanks.