- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Utah War In Wyoming

The Utah War in Wyoming

Elizabeth Cumming, cultured, observant and intelligent, suffered from a frostbitten foot, which then swelled and burst. It was November 1857; she was on the trail with her politician husband and a company of U.S. cavalry. No one was quite sure what the winter would bring.

|

Cumming and her husband, Alfred, would spend the winter in a tent near Fort Bridger in present southwest Wyoming. Alfred Cumming was the newly appointed governor of Utah Territory, en route with an Army escort to his new position. The couple had traveled from Fort Leavenworth in eastern Kansas Territory with a column of dragoons led by Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke.

Their destination was Salt Lake City. But “we must stop here all winter,” she wrote home, “where there is wood and water. …There was no wood to burn [on the journey]—& the weather intensely cold. … Sometimes had no food at night.”

Cooke’s unit was part of the Utah Expedition, a larger force of U.S. soldiers ordered to Utah Territory by President James Buchanan more than five months earlier. The expedition’s purpose was to escort Gov. Cumming and install and support him in his new position with military force if necessary.

Buchanan, inaugurated on March 4, 1857, was facing a set of serious, interconnected problems, of which Utah was only one. Strong forces were pulling the nation apart.

With the Civil War just four years off, slavery divided the nation more deeply each month, it seemed. A South Carolina congressman attacked a Massachusetts senator on the floor of the Senate and beat him nearly to death with a cane. Conflict between pro- and anti-slavery forces in Kansas led to the establishment of competing territorial legislatures and soon to bloody, armed conflict between the factions.

The Mormons

Farther west, too, a new power was growing and resisting federal authority. The first pioneer parties of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—had reached the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. Utah Territory was organized in 1850. For a time it stretched from California to the Continental Divide, including all of what is now Utah together with large parts of Nevada, Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. Church President Brigham Young was appointed governor of the new territory. By Buchanan’s time, converts were arriving not just from the American frontier but from Britain and Scandinavia as well.

By the time Buchanan was elected in 1856, there may have been 35,000 Mormons in Utah Territory. Though Young’s term as governor had expired in 1854, he was still legally in office because no successor had taken his place.

Buchanan’s predecessors in the White House had failed to act decisively on what had become the Utah problem. Profound suspicion and distrust existed between Mormons and the rest of the nation, due in part to the Mormon practice of polygamy, and to Mormon feelings of persecution in the wake of decades of violent conflict between their members, their Nauvoo Legion militia, and other non-Mormons and state militias.

Several times during the 1850s non-Mormon officials appointed to govern Utah Territory served briefly, resigned their posts and returned to Washington. They reported that Young and his ruling council obstructed them in their duties, sometimes with threats of violence or by ordering actual assaults.

The Mormons maintained that gentile officials—gentile was their term for all non-Mormons—were often rude, often incompetent, tried to fraternize with Mormon women, drank, interfered with the administration of the territory’s laws and thus made themselves unwelcome. A small percentage of U.S. officials, whether civilian or military, had in fact occasionally misbehaved, and this partly substantiated Mormon claims of persecution and interference—and their recurring fear of violence.

A late start for the Army

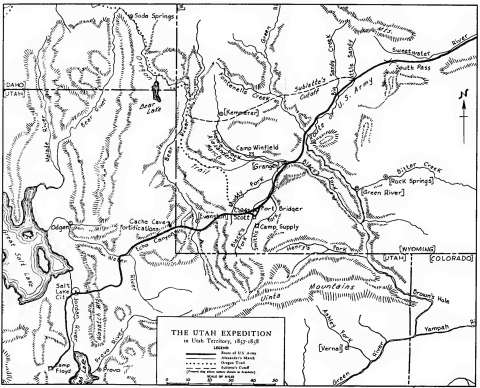

Sometime within the first two months of his presidency, Buchanan decided to send federal troops to Utah to ensure the successful installation of a new governor and a slate of territorial officers, including a chief justice and a superintendent of Indian affairs. Their route would take them on the Oregon-Mormon Trail directly across what is now Wyoming. They started dangerously late, however, and multiple factors complicated their logistics.

Late in May, Winfield Scott, the U.S. Army’s general in chief, announced the expedition to his top officers and outlined the logistics for transport and supply. He informed Brevet Brig. Gen. William S. Harney, a veteran of Indian Wars along the North Platte River, that Harney would probably lead the expedition. Harney also ordered supply wagons from the St. Louis firm of Russell, Majors and Waddell. These slow-moving supply trains, without military escorts, were well on their way by mid-June.

Troops had to be gathered from Minnesota, Kansas and the Florida Everglades. Many spent June and the first half of July recovering from fevers and wounds.

On July 13, Cumming received his new commission, but he and his fellow officials needed still more time to prepare and to convene at Fort Leavenworth before starting out.

Col. Edmund Alexander, an irresolute and unpopular officer, left Fort Leavenworth on July 18 with units of the 10th Infantry Regiment. Other infantry and artillery companies followed, marching separately and without supporting cavalry.

On July 21, Gen. Harney sent Capt. Stewart Van Vliet, an officer the Mormons knew and trusted, to travel at top speed to Salt Lake City. Harney and his superiors hoped that Van Vliet could confer with Brigham Young to learn whether the Mormons would be willing to sell the Army hay, oats, corn or barley for their animals and lumber for their camp.

At the last minute, due in part to pressure from the Kansas governor, who wanted Harney’s help with the difficulties he faced, the secretary of war replaced Harney with Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, then serving in Texas. Johnston rushed from San Antonio to Fort Leavenworth.

Elizabeth Cumming’s first letter about her journey, dated Aug. 25, 1857, “On Missouri River,” reflected some of the expedition’s confusion and uncertainty. She wrote, “We are now on our way to Leavenworth City [about three miles south of Fort Leavenworth], to see if orders have arrived, or if we can make some arrangement there … to enable us to get on.”

Cumming’s party finally left Fort Leavenworth Sept. 17. Col. Johnston’s party was the last to leave, on Sept. 18. He planned to travel rapidly, guided by mountain man Jim Bridger, to reach the head of the immense cavalcade stretching west from Fort Leavenworth. Desertions and sickness had reduced by several hundred the original 2,500 soldiers sent.

Capt. Van Vliet, meanwhile, arrived in Salt Lake City on Sept. 8.

Fear in Utah Territory

In Utah, tensions had been rising all summer as reports, rumors and wild tales trickled in from the East. Late in May, Utah Territory’s delegate to Congress, John M. Bernheisel, a Mormon, had arrived in Salt Lake City, confirming what Young had already heard from his far-flung network of scouts and couriers: Buchanan planned to replace him. A month later, Young learned troops were mobilizing at Fort Leavenworth.

Further, a U.S. Army expedition ordered to the plains that summer to fight the Cheyenne Indians was an additional source of anxiety. Many Mormons were ready to believe these troops would soon attack them.

Panic and fear spread throughout the territory. On Sept. 11 at Mountain Meadows, 300 miles south of Salt Lake, militiamen of the Nauvoo Legion, together with a group of Paiute Indians, slaughtered 120 members of an Arkansas wagon train en route to California.

To Van Vliet, meanwhile, Young was adamant: No Mormon would sell supplies to the U.S. Army. The officer left Salt Lake City on Sept. 14, having heard nothing of the massacre.

The following day, Young issued a proclamation. It began, “We are invaded by a hostile force, who are evidently assailing us to accomplish our overthrow and destruction. … Our opponents have availed themselves of prejudice existing against us, because of our religious faith.” Finally, Young declared martial law in Utah Territory, adding, “no person shall be allowed to pass or repass into, or through, or from this Territory without a permit from the proper officer.”

Utah Territory was more than 600 miles wide and the principal emigration trails crossed it. The proclamation threatened to close off transcontinental travel.

Finally, Young and many of his followers believed that the Army’s imminent attack was an apocalyptic event preceding the second coming of Christ. On Sept. 14 and 21 Young preached fiery sermons. Bishops and teachers went house to house, chastising residents for their behavior and publishing the names, addresses and offenses of those who confessed. Most terrifying of all was the doctrine of “blood atonement,” under which, for certain sins, only the loss of the blood and life of the sinner was sufficient sacrifice to save that person’s soul. Mormons no longer believe in or practice this.

The Army on the march

On the night of Sept. 24-25, Mormon guerillas raided the indecisive Col. Alexander’s infantry company, camped on Pacific Creek about 12 miles southwest of South Pass on the Oregon Trail in what’s now west-central Wyoming. The Mormons tried and failed to stampede the mules because the bell mule, which the others were trained to follow, tangled its picket rope in sagebrush.

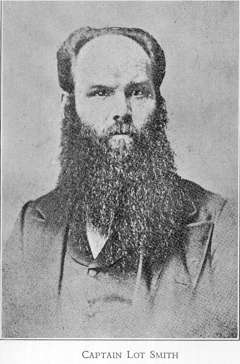

Ten days later, the Mormons struck again. On Oct. 4, a unit led by Nauvoo Legion Maj. Lot Smith attacked three different trains of Russell, Majors and Waddell within 24 hours, burning a total of 76 wagons. The first train was on the Big Sandy River, about 10 miles southwest of present Farson, Wyo., at a place later named Simpson's Hollow for wagon master Capt. Lew Simpson.

The other two trains were camped nearby on Green River, with troops no more than 15 miles west of them. Twenty-five years later Lot Smith recalled, “I inquired of Dawson [one of the wagon masters] what kind of loading he had, as I was much in need of overcoats for my boys [soldiers].” Dawson supplied the overcoats and other clothing, and then had to watch his wagons burn.

Throughout October, Smith’s band and other Mormon parties stampeded cattle intended for the U.S. Army’s winter meat, and burned so much grass that despite supplies of corn the companies carried with them, many draft horses, mules and cattle starved.

About the time Smith burned the wagons, the Cumming party was passing through central Nebraska Territory in a severe rainstorm. When they reached Fort Laramie Oct. 24, word of the attacks near South Pass awaited them. Elizabeth wrote the news to her sister-in-law, adding, “We hear that the snow is already two feet deep in the mountains, & seven inches on the prairies beyond us.”

Col. Alexander, meanwhile, was camped on Ham’s Fork about 30 miles west of Simpson’s Hollow with more supply trains and the regiments that had caught up,

Alexander and Young had exchanged letters in late September. Still writing as governor of Utah Territory, Young informed Alexander that he would permit the troops to remain on Ham’s Fork for the winter, if Alexander consented to depart with his troops in the spring. Young further stipulated that Alexander turn all arms and ammunition over to the Mormon stalwart Lewis Robison, a former ferryman on the Green River, now quartermaster general of the Territory.

Near Ham’s Fork, one of Alexander’s patrols captured Nauvoo Legion Maj. Joseph Taylor and his adjutant. Alexander’s men found that Taylor carried written orders, dated Oct. 4, from Nauvoo Lt. Gen. Daniel H. Wells.

“[P]roceed at once to annoy [the U.S. troops] … in every possible way,” the orders read. “Use every exertion to stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them, and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping by night surprises; blockade the road by felling trees or destroying river fords. … [S]et fire to the grass on their windward so as if possible to envelop their trains. Leave no grass before them that can be burned.” In a postscript Wells added, “Take no life but destroy their trains and stampede or drive away the animals at every opportunity.”

By Oct. 26, Johnston had reached South Pass and was waiting for remaining companies. Via courier, Johnston ordered Alexander to meet him at Black’s Fork, near present Granger, Wyo. By Nov. 3, all the various troops except Cooke’s, escorting the Cumming party, were in one place and under the expedition leader’s command — for the first time in nearly four months.

Johnston knew he must find a place to winter, and decided on Fort Bridger. He planned to enter Salt Lake Valley in the spring, via Echo Canyon, along the route of present Interstate 80.

For their part, Cooke and the Cummings were approaching Three Crossings on the Oregon Trail, a few miles north of present Jeffrey City, Wyo, when a severe storm hit. “The air seemed turned to frozen fog,” Cooke wrote. “[N]othing could be seen. We were struggling in a frozen cloud.”

A hungry winter

In the same blizzard, Johnston’s column began marching southwest along Black’s Fork toward Fort Bridger, 35 miles away. This trek was the major ordeal of the campaign. Draft horses and mules died of starvation and thirst. Wagons had to be abandoned for later retrieval. Sagebrush, sparse and buried in the snow and ice, was the only fuel.

On their Nov. 17 arrival at Fort Bridger—burned and abandoned by the Mormons six weeks earlier—Johnston set up camp nearby, naming it Camp Scott after the general in chief.

Cooke’s party arrived two days later. Near Camp Scott, Eckelsville, named after new chief justice of Utah Territory Delana R. Eckels, was established for the civilians, including the supply trains not burned by the Mormons.

On Nov. 28, Elizabeth Cumming described the last few days of their journey. “Thermometer below Zero in the day—at night not only cold, but wind. We left 200 animals dead; we loosed the harness & they fell on the road.”

On Nov. 30, two men arrived at Camp Scott from Salt Lake Valley with 800 pounds of salt and a letter from Brigham Young, mentioning that he knew the entire company was out of salt. Young assured Johnston that his gift was not poisoned.

Johnston, who indeed had no salt, had ordered some from Fort Laramie about three weeks before. He refused all 800 pounds, because he would “not accept a present from an enemy of my government.”

Life in camp turned out to be much easier than the journey, despite reduced provisions. On Dec. 13, Elizabeth Cumming wrote, “[T]hough the hills around us are very bleak & windy, we are encamped in a basin, so surrounded by hills, that the winds reach us very gently. … A most rigid economy in … [the distribution of provisions] is necessarily observed, to give us some assurance of being fed till Spring.”

The Cummings had additional private food stores, but the common soldiers lived on 10 ounces of flour and 4 ounces of fat pork per day, and coffee once a week. On these rations, they had to cut firewood and haul the loaded wagons, part of their regular camp duties.

Alfred Cumming and the other Buchanan appointees administered the Utah Territorial government as best they could, in a tent 75 miles from its capital, as did Johnston and his staff at Camp Scott.

On Dec. 30, 1857, Judge Eckels convened a grand jury that indicted Brigham Young, Daniel H. Wells, John Taylor and “one thousand [other] persons and more” on four counts of treason. Key documents in the case were Young’s Sept. 15 martial-law proclamation and Wells’s Oct. 4 orders to Taylor. The case later failed on procedural grounds.

Gaining Salt Lake Valley

On April 5, 1858, Alfred Cumming left Fort Bridger for Salt Lake City, escorted by Thomas L. Kane, a longtime friend of the Mormons and self-appointed intermediary between Brigham Young and the federal government. Kane had been in Salt Lake Valley conferring with Young for more than a month.

When Young announced he would welcome Cumming, Kane apparently credited his own influence with Young. However, most sources suggest that news Young received on March 8 was the real deciding factor: In late February, Indians had attacked and taken over Fort Limhi, a Mormon outpost 400 miles north of Salt Lake City near present Salmon, Idaho, in the Salmon River Valley. With the cutting off of this last-ditch northern retreat—or perhaps escape route—Young may have realized he had few options left, and armed resistance to the U.S. Army was not one of them.

Near the end of May, Buchanan offered a pardon to the inhabitants of Utah Territory for their “seditions and treasons” if they agreed to obey the federal government. Brigham Young’s response would determine whether Johnston and his men marched into Salt Lake Valley as occupiers or as helpers and protectors of loyal citizens.

Young capitulated, at least outwardly. On June 26, Johnston and his troops entered Salt Lake City, largely deserted due to a prior order by Young to “move south.” Still suspicious, the Mormons were prepared to burn the city as well as their homes farther south in the valley, and retreat to the mountains.

This did not happen. Johnston established a camp about 40 miles south of Salt Lake City near present Fairfield, Utah. He named it Camp Floyd, in honor of the secretary of war. His men behaved well, and there was no looting, drinking or pursuit of Mormon women.

After the Utah War

Elizabeth Cumming remained in Salt Lake City with her husband until May 1861, when his term expired. The couple traveled to Washington D.C. to settle accounts and prepare to return to Cumming’s family home in Augusta, Ga. The Civil War, however, delayed their return until summer 1864.

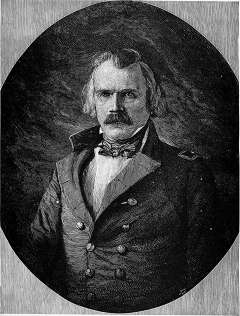

Johnston, promoted to brevet brigadier general in spring 1858, served at Camp Floyd until February 1860. Subsequently Johnston joined the Confederate Army and was commissioned a general. He was killed at the battle of Shiloh in April 1862, the highest-ranking Confederate officer to be killed in the war.

Many sources refer to the Utah conflict as a “bloodless war” because there were no armed clashes between the two sides. However, historian William MacKinnon argues that civilian deaths cannot be ignored. In addition to the 120 defenseless people killed at Mountain Meadows, MacKinnon cites seven other murders in 1857 and 1858, in or near the Salt Lake Valley. Mormons were proven to have committed at least six; one man was beaten to death in his sleep while a prisoner of the Mormons. Systematic, thorough looting accompanied all 127 of these murders.

MacKinnon notes too that the federal government was not without blame as, he writes, the assault on Fort Limhi was federally provoked.

Some writers have dubbed the Utah Expedition “Buchanan’s Blunder,” but historians David Bigler and Will Bagley suggest that conditions forced Buchanan to order the expedition, and he did the best he could under the circumstances in an extremely difficult time.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Canning, Ray R. and Beverly Beeton, eds. The Genteel Gentile: Letters of Elizabeth Cumming, 1857-1858. Utah, the Mormons, and the West Series, no. 8. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Tanner Trust Fund.

- Hafen, LeRoy and Anne W. Hafen, eds. The Utah Expedition 1857-1858: A Documentary Account of the United States Military Movement under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, and The Resistance by Brigham Young and the Mormon Nauvoo Legion. The Far West and the Rockies Historical Series 1820-1875, vol. 8. Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1958.

- Hammond, Otis G. The Utah Expedition 1857-1858: Letters of Capt. Jesse A. Gove, 10th Inf., U.S.A., of Concord, N.H., to Mrs. Gove, and special correspondence of the New York Herald. New Hampshire Historical Society Collections, vol. 12. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1928.

- Johnston, Col. Albert Sidney. “Colonel Johnston to Army Headquarters, Nov. 5, 1857.” In Hafen, LeRoy and Anne W. Hafen, eds. The Utah Expedition 1857-1858: A Documentary Account of the United States Military Movement under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, and The Resistance by Brigham Young and the Mormon Nauvoo Legion. The Far West and the Rockies Historical Series 1820-1875, vol. 8. Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1958, 158-165.

- Library of Congress. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Accessed Oct. 11, 2017, at chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- The New York Herald, May 24, 1858, May 27, 1858, June 9, 1858, July 8, 1858.

- Phelps, Capt. John W. Diary. In MacKinnon, William P., ed. At Sword’s Point, Part I: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858. Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier, vol. 10. Will Bagley, series editor. Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008, 382.

- ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Accessed Oct. 10, 2017, at www.proquest.com:

- The Daily Dispatch [Richmond, Va.], Nov. 12, 1857

- New-York Daily Tribune, Nov. 16, 1857

- The New York Herald, Nov. 18, 1857

- The Sun [Baltimore, Md.], Nov. 17, 1857

- Smith, Lot. “Narrative of Lot Smith.” In Hafen, LeRoy and Anne W. Hafen, eds. The Utah Expedition 1857-1858: A Documentary Account of the United States Military Movement under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, and The Resistance by Brigham Young and the Mormon Nauvoo Legion. The Far West and the Rockies Historical Series 1820-1875, vol. 8. Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1958, 220-246.

- Wells, Daniel H. “Orders to Major Joseph Taylor, Oct. 4, 1857.” In MacKinnon, William P., ed. At Sword’s Point, Part I: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858. Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier, vol. 10. Will Bagley, series editor. Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008, 349-350.

- Young, Brigham. Letter to Colonel Alexander, Sept. 29, 1857. In Hafen, LeRoy and Anne W. Hafen, eds. The Utah Expedition 1857-1858: A Documentary Account of the United States Military Movement under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, and The Resistance by Brigham Young and the Mormon Nauvoo Legion. The Far West and the Rockies Historical Series 1820-1875, vol. 8. Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1958, 61-62.

- _____________. “Proclamation by the Governor.” Sept. 15, 1857. In MacKinnon, William P., ed. At Sword’s Point, Part I: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858. Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier, vol. 10. Will Bagley, series editor. Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008, 286-288.

Secondary Sources

- Bigler, David L., and Will Bagley. The Mormon Rebellion: America’s First Civil War, 1857-1858. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

- “Bleeding Kansas.” Wikipedia. Accessed Nov. 8, 2017 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bleeding_Kansas#cite_ref-9.

- Carroll, Murray L. “The Wyoming Sojourn of the Utah Expedition, 1857-1858.” Annals of Wyoming 72, no.1 (Winter 2000): 6-24. Accessed Sept. 10, 2017, at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom72142000wyom.

- Furniss, Norman F. The Mormon Conflict 1850-1859. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960.

- Gardner, Hamilton, ed. “March of 2d Dragoons: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke on the March of the 2d Dragoons From Fort Leavenworth to Fort Bridger in 1857.” Annals of Wyoming 27, no.1 (April 1955): 43-60. Accessed Sept. 10, 2017, at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom2427wyom.

- MacKinnon, William P., ed. At Sword’s Point, Part I: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858. Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier, vol. 10. Will Bagley, series editor. Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008.

- Rea, Tom. Devil’s Gate: Owning the Land, Owning the Story. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, 78-98.

- Roberts, David. Devil's Gate: Brigham Young and the Great Mormon Handcart Tragedy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008, 86.

Illustrations

- The photo of Elizabeth Cumming is from the Utah State Historical Society. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the trail near Simpson’s Hollow is by Tom Rea.

- The map of the route of the Utah Expedition was first published in Documentary Account of the Utah Expedition, 1857-1858, by Leroy and Ann Hafen, published by the Arthur H. Clark Company, 1962. Used with permission of and thanks to the University of Oklahoma Press.

- The images of Albert Sidney Johnston, Brigham Young, Alfred Cumming and Lot Smith are all from Wikimedia Commons. Used with thanks.