- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Spreading The Gospel: Lutheran Missionaries At ...

Spreading the Gospel: Lutheran Missionaries at Deer Creek, 1859-1864

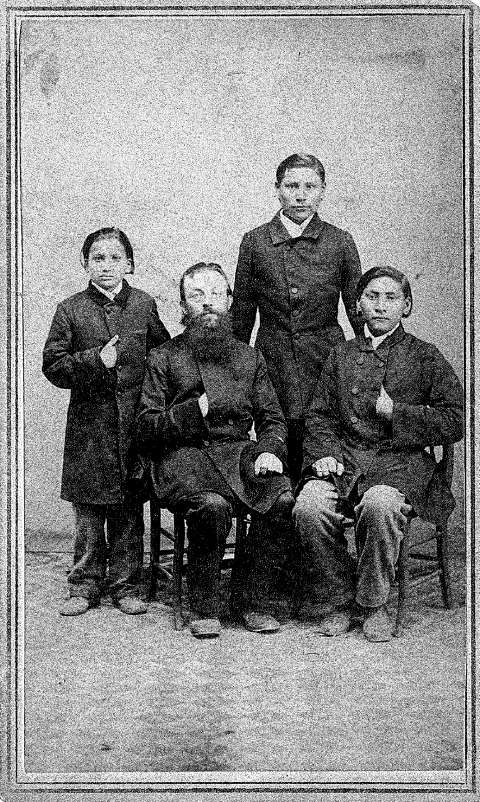

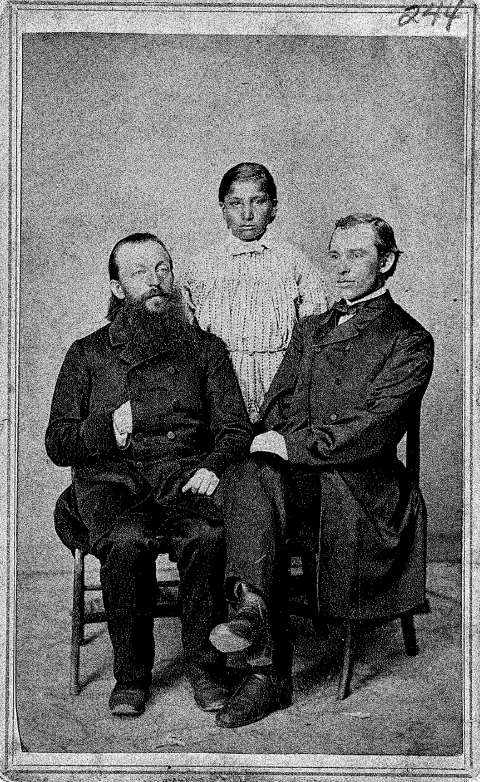

Three young boys arrived at Wartburg Seminary near Dubuque, Iowa, with their Lutheran custodians late in 1864. Known by their baptismal first names of Gottfried, Paulus and Friedrich, their hair was cut short and they dressed in the manner of Lutheran men. In actuality, they were Cheyennes from the Rocky Mountains and their translated names were Brown Moccasin, Little Bone and Owl Head. In a way, they were the only clear evidence of a failed nine-year effort by German Lutherans to convert Native peoples to Christianity.

The Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Iowa, founded in 1854, followed the teachings of Rev. Wilhelm Loehe of Bavaria, a man vitally interested in organizing German immigrants into American congregations and in converting Native peoples to his faith. His goals motivated Rev. Johann Jakob Schmidt, who traveled to Canada in the summer of 1856 and to Lake Superior the year following. Opposition by Jesuits and the Hudson Bay Company stifled his efforts to proselytize among the Indians.

In 1858, Schmidt would not give up, writing that “the territory which appeals to me most of all, is . . . just east of the Rocky Mountains in the head waters of the Missouri River. The people are the Crows and Blackfeet.” With the encouragement of the agent to Indians of the Upper Missouri Agency, Schmidt, along with Rev. Moritz Braeuninger, traveled on the steamboat Twilight up the Missouri River to Fort Union and then up the Yellowstone River to Fort Sarpy, near the mouth of Rosebud Creek. Throughout their journeys and those that followed, they would be handicapped by the fact that they spoke only German and had minimal financial support, most of it from Bavaria and Germany.

At Fort Sarpy, the missionaries were confounded by what they described as the low morals of traders and Indians alike, describing the American Fur Company post as “the sewer of Satan.” Departing with the Crow they began studying their language, traveling for seven weeks through the Tongue and Powder River country. Finally, ending up at Deer Creek and the Upper Platte Indian Agency, the missionaries traveled back east with Maj. Thomas Twiss, Indian agent to tribes on the upper North Platte. At Wartburg Seminary in Iowa they prepared to return to Deer Creek and from there to establish a mission in the Crow country. For the next six years Deer Creek—near present Glenrock, Wyo.—would remain their base of operations.

Setting up on Deer Creek

In the fall of 1859, six men arrived at Deer Creek. They included Missionaries Johann Schmidt, Moritz Braeuninger and Ferdinand Doederlein. To help them were three colonists, Theodore Seyler and men named Beck and Bunge. Funds from Bavaria and Germany supported the cost of travel and supplies, but upon arrival they had with them only $20.00, a half sack of flour and a side of bacon. They met with trader and postmaster Joseph Bissonette and Indian agent Twiss, both of whom contributed clothing and some supplies to the missionary efforts. Bissonette promised store credit until they received more funding.

Shortly, Capt. William F. Raynolds of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical engineers, heading an expedition to explore country drained by the Yellowstone River, also arrived. Raynolds’s men prepared log winter quarters and supported the missionaries by employing Beck and Bunge to help them. This was not enough, so that Schmidt and Doederlein left for Iowa to seek more funds and supplies so that in the spring a mission in the Powder River country could be built.

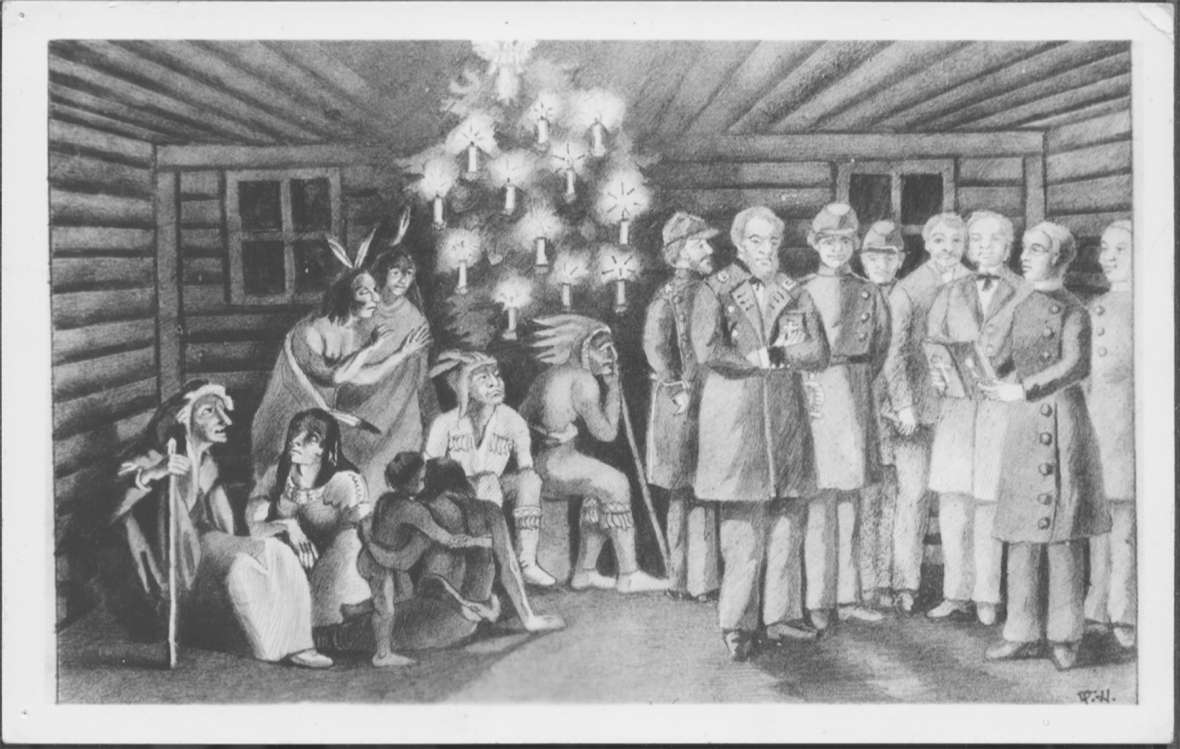

Through the winter the missionaries managed to get by, holding religious services and doing the best they could. Maj. Twiss provided them with housing in buildings abandoned by Mormons during the Utah War in 1857. This is where they celebrated the Christmas of 1859 with Capt. Raynolds reading scriptures in English and Braeuninger giving the gospel in German. They sang hymns, enjoyed a Christmas tree and presented small gifts to Indians in attendance.

Raynolds later reported that the missionaries were “God-fearing and devoted men, but ignorant of the world as well as of our language, and in consequence poorly fitted for the labors they had undertaken.” He felt that he was “instrumental in enabling them to pass a more comfortable winter than would otherwise have been their lot.” In fact, Raynolds, geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden and expedition artist Antoine Schoenborn were among fifteen men in the government party contributing $60.00 to support the missionaries.

A mission on Powder River—briefly

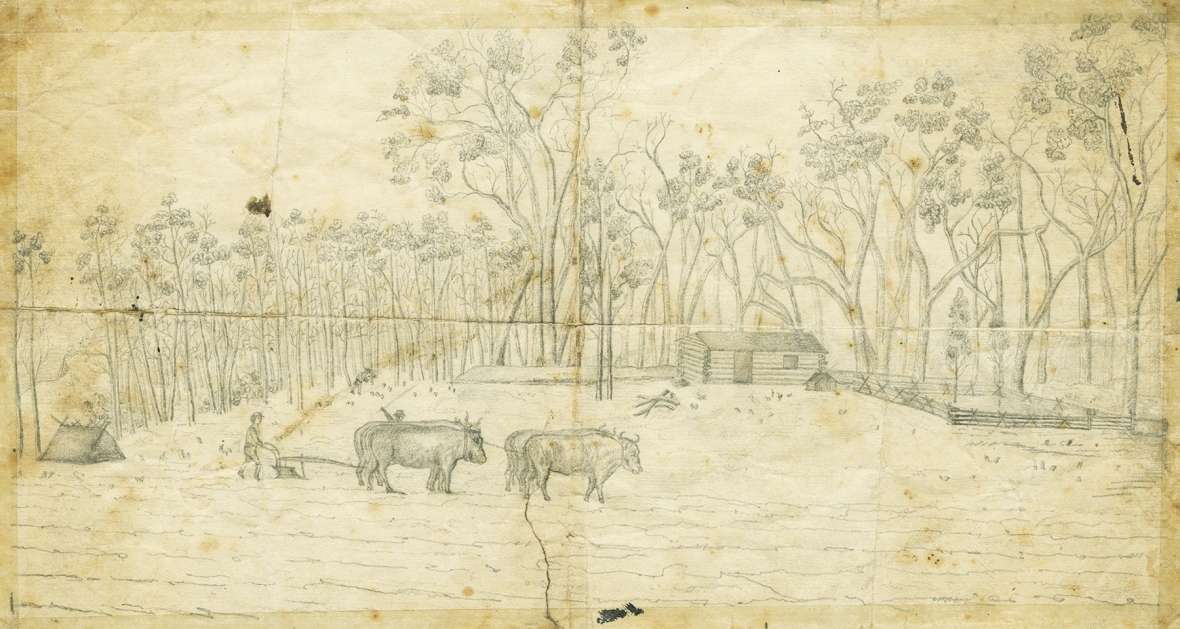

As the Raynolds expedition departed Deer Creek in early 1860, the missionaries embarked on a year that challenged their faith and endurance. In the spring, trader Bissonette extended more credit to them for the purchase of supplies and at long last, under the leadership of Rev. Moritz Braeuninger, an entourage of missionaries and laborers followed a 96-mile route surveyed under Raynolds by J. D. Hutton. Proceeding some distance more, they entered Sioux country, stopping on the northwest side of Powder River opposite to where Dry Fork drains into the main channel. (This places them at a location that would become better known within a few years as the Powder River crossing of the Bozeman Trail.)

Here they built a mission with a house and a small farm from which they could sustain themselves and pursue converting the Crow people to Christianity. Although they were aware of the traditional animosity and open warfare between the Crow and Lakota, they never imagined what they would face.

There were a number of contacts between the missionaries and Lakota warriors. At first seemingly friendly, six Lakota arrived at the Powder River mission on July 22, 1860. During the ensuing events, Rev. Braeuninger was shot and killed, causing deep sorrow within the Lutheran community. The Powder River establishment was abandoned and never reestablished.

More support for the Deer Creek operation

September brought new funds from Germany and new staffing in the persons of Karl Krebs and Christian Flachenecker, who arrived by stagecoach. A decision had been made to build a mission at Deer Creek, leading to new construction four miles from Bissonette’s trading post and two miles west of the Indian agency. It was reported that “the soil is good here. There are three springs on our land and the shores of the creek do not offer any particular difficulties in putting in some irrigation ditches.”

By the spring of 1861, the new establishment was coming along nicely. Timber was cut for a new house, Twiss built a stone chimney for them and contributed a laborer to help. He also donated wooden boxes that had contained Indian annuity goods. These were used to construct cupboards, beds, tables, chairs and flooring. Most importantly, the Rev. Christoph Kessler arrived to take charge of the operation and Krebs and Flachenecker were ordained.

Missionaries witnessed stagecoach operations from Bissonette’s location and in 1860 the Pony Express and in 1861 the transcontinental telegraph operations added to the vitality of the region. As the Civil War flamed in the East, the Lutherans developed their farm. They built a 70-foot-long by 9-foot-wide dam of stone and dirt across Deer Creek. It was not effective; for several seasons, gardens planted with corn, peas, onions, potatoes and other crops failed under the assault of dry weather and the onslaught of mice and grasshoppers.

Cheyenne and Arapaho contacts

After the administration of Abraham Lincoln took office early in 1861, Twiss resigned his position and was replaced by an appointee not friendly toward the Lutherans; the new agent moved the agency east to Fort Laramie. Lutheran efforts to work with the Crow people continued to fail, but efforts to engage with Cheyenne and Arapaho people camped nearby were more successful.

For the next several years, missionaries traveled for months at a time, especially with the Cheyenne, who also attended religious services at the mission. Sometimes months would pass without contact and efforts to entice a Cheyenne family to stay at the mission were only partially successful. Work to record the Cheyenne language progressed, however, and Krebs became proficient at communicating and giving services in the language.

Struggles during 1862 found the missionaries in conflict with traders, especially those selling whiskey to the Indians. Thomas Twiss remained at his ranch nearby but became less supportive of the missionaries. Also in that year, Indian attacks along the stage line led to the temporary abandonment of the mission and a brief residence for the staff at Fort Laramie. That summer, the Overland stage line was moved to a southern route along the Overland Trail to Salt Lake City. The abandoned stage station at Deer Creek remained in use as a telegraph relay station—and became a military post garrisoned by Ohio cavalrymen.

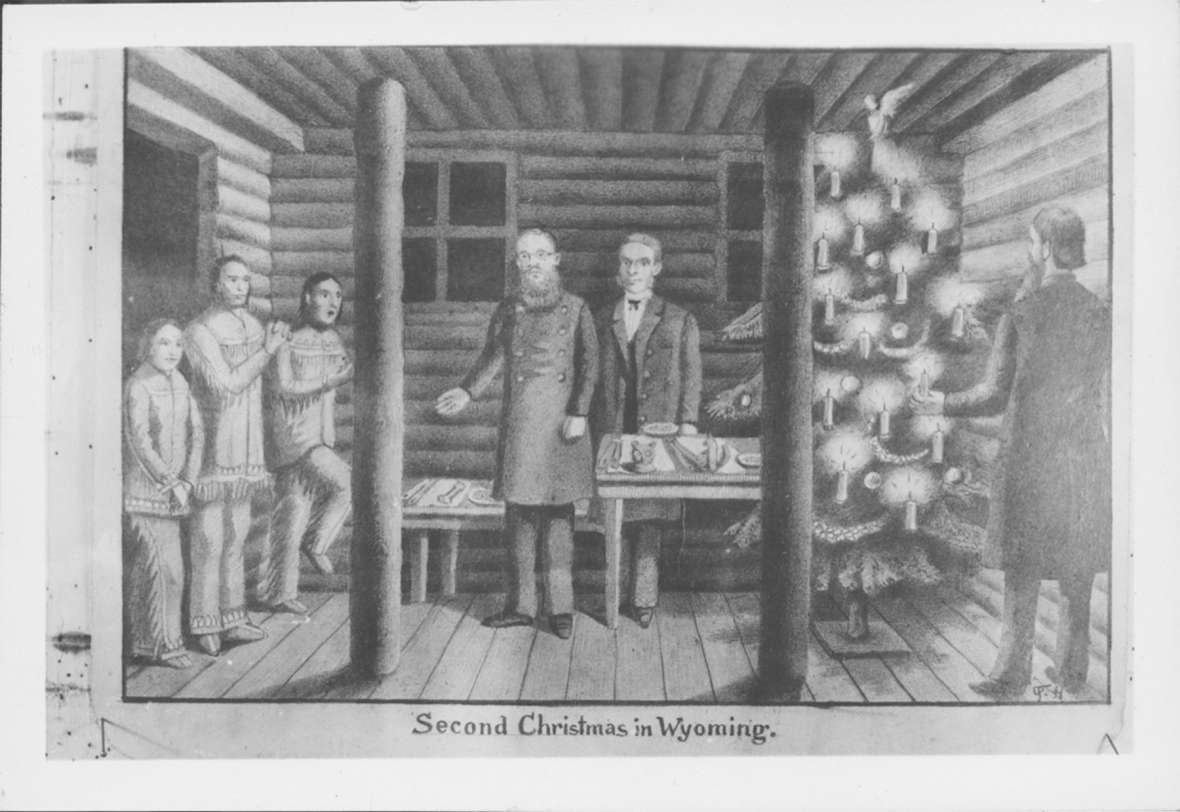

In 1863 the missionaries traveled with the Cheyennes while for a period of time as many as 250 lodges were pitched at Deer Creek. Even with this, there was little success. In the spring, Kessler returned to Iowa and came back with renewed supplies and equipment along with his wife, the fiancé of Mr. Beck and her brother and the Reverend Franz Matter.

Three Cheyenne boys

This same year found the missionaries feeling hopeful as they assumed the care of three Cheyenne boys. Even though some parents and other Cheyenne relatives claimed and visited them, the boys were defined by the missionaries as orphans. They were dressed in suits like the missionaries, but as in the case of Little Bone, were viewed as being “just an Indian in the garments of whites.”

Krebs reported that “we found him to be [a] vivacious, intelligent, clever and cunning lad who had to be watched and trained.” In doing so, the missionaries focused on lessons in religious teachings, language and manners. Failures to obey instructions sometimes resulted in severe punishment. One Cheyenne father promised to shoot a missionary if he punished his son, but nothing came of this. Even so, it was felt that there was a closeness between the boys and the Lutherans.

On Christmas eve 1863, the boys were enthralled by a tree decorated with candles and happily received presents, including harmonicas which they played late into the night. On Christmas day, the youngest boy, Brown Moccasin, was baptized and renamed Frederick B. Sigmund Christopher. Little Bone’s baptism followed the next Easter. He was renamed Paul.

Trouble on the trail

As the summer of 1864 approached, the mission had been much improved. The original cabin became a warehouse and four other buildings served as quarters for the staff. One of these doubled as a church and another as the school and dining room. A separate structure served as the kitchen for the compound. But there were signs of trouble along the Oregon Trail.

In July, Sioux warriors attacked a wagon train, killed the emigrants and captured two children along with Sarah Larimer and Fanny Kelly. The Lutherans withdrew to an abandoned trader’s building at Deer Creek Station. The mission property, left unguarded, suffered damage and goods were stolen.

Missionary Krebs attributed the losses to Ohio troops at Deer Creek. Even though many of the troopers spoke German, relations between soldiers and the Lutherans were generally poor. By September Krebs observed that “two soldiers, one more drunk than the other, behaved like swine. Boys sneaked into the woods out of fear of them.”

The concern for Indian attacks continued to grow. Soon, as more and more miners, merchants and families left the Platte River Road to travel north through tribal lands to the gold fields of Montana, Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors began frequently attacking the travelers. War escalated further after the Sand Creek Massacre late in 1864 when, the following summer, the tribes attacked the Army post at Platte Bridge Station, 25 miles upriver from Deer Creek.

Krebs wrote, “we saw the time when we would have to flee approaching nearer, and the ruin of our work stood before our eyes. In case of an attack we could not expect that the soldiers would protect us, beyond the fact that they would protect themselves. Inwardly depressed by anticipations, outwardly surrounded by constant dangers, we stood there all alone.”

Driven out

The mission council in Iowa now ordered the Deer Creek mission to be abandoned, remaining goods were sold at a loss, Franz Matter and Christian Flachenecker were ordered to stay at Fort Laramie and the rest, including the Indian boys, returned to Iowa. In January 1865, they were followed by Matter and Flachenecker. The Lutheran Synod mission was finished, except for a season spent by Franz Matter, Carl Krebs and Friedrich Sigmund Christoph at Fort Cottonwood in Western Nebraska. There, work focused upon producing a formal Cheyenne grammar and dictionary and the missionaries, with the help of the one Cheyenne boy still living, translated the Gospel according to St. Luke.

Franz Matter reported that they were recalled in April 1867. Matter lamented that “Our Mission among the Indians was buried when we left.” The remaining funds to support the Lutheran mission to the Indians were held until 1888—and finally used to organize a mission to Papua, New Guinea.

What of the Cheyenne boys? Paul—Little Bone—died from tuberculosis in August 1865. Gottfried—Brown Moccasin—after being baptized, fell victim to the same disease in December of that year. Both were buried at the St. Sebald cemetery in Clayton County, Iowa. Frederick—Owl Head—abandoned his teachers and wandered the region, working to support himself and going by the name of Fred Green. He died in 1876 and is buried at Andrew, Iowa. In the late 1950s, Cheyenne historian John Stands In Timber remembered the boys being sent east and that their Cheyenne families never entirely knew what happened to them.

Resources

Special thank you to Tamsen Hert, Librarian, Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections at the University of Wyoming Library and Sue Dodd, archivist at the Wartburg Theological Seminary, Dubuque, Iowa, for making information and images available for this article.

- Bryans, William S. Deer Creek: Frontiers Crossroad in Pre-Territorial Wyoming, Glenrock: Glenrock Historical Commission, 1990.

- Fritschel, Erwin. G. A History of the Indian Mission of the Lutheran Iowa Synod, 1856 to 1866. Doctoral dissertation, Colorado State College of Education, 1939.

- Fritschel, Rev. George J., translator. Rev. Franz Matter In the Service of the Indian Mission, 1863-1866. Dubuque, Iowa, 1938. University of Wyoming Library, Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections.

- Fritschel, Rev. George J., translator from Kirchenblatt der Synode von Iowa. Articles Concerning Indian Missions, 1858-1866, 1937. University of Wyoming Library, Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections.

- Krebs, Karl Gottlieb. RG1146.AM, Diary in German 1864-1865, Deer Creek Mission, translated by Marie Nausler for Nebraska State Historical Society, RG0876, Deer Creek Mission.

- Schmutterer, Gerhard M. Tomahawk and Cross, Lutheran Missionaries among the Northern Plains Tribes, 1858-1866. Sioux Falls, South Dakota, The Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, 1989.

- Stands In Timber, John and Margot Liberty. A Cheyenne Voice: The Complete John Stands In Timber Interviews. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

- Ottersburg, Gerhard Sigmund. The Evangelical Lutheran Synod of Iowa and Other States 1854-1904. Master’s Thesis, University of Nebraska, 1949.

- Moldenhauer, Roger, editor. "The Doederlein Diary, 17 May 1859--February 1860," Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly, fall 1978.

- Raynolds, William F. Report on the Exploration of the Yellowstone River. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1868, accessed April 13, 2022 at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015011349597&view=1up&seq=7&skin=2021.

- Wagner, Oswald. “Lutheran Zealots Among the Crows,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 22 (April 1972), 2-19.

Illustrations

- The two Samuel Root photographs of the missionaries and Cheyenne boys are courtesy of the archives at Wartburg Theological Seminary, Dubuque, Iowa. Used with permission and thanks.

- The drawings of the missionaries on two different Christmases at the Deer Creek mission are from History Nebraska. Used with thanks.

- The sketch of the oxen plowing at the mission on Powder River is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.