- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Crossing The North Platte River

Crossing the North Platte River

Emigrants bound for Oregon, California and Utah in the mid-1800s faced high tolls and high risks when they crossed the North Platte River near present Casper, Wyo. River crossings were extremely dangerous; operators of commercial ferries and bridges charged steep prices for safety. Many emigrants, unwilling to pay, cobbled together other, more homemade solutions—with varying success. Until bridges were built, nearly all travelers swam their livestock across, and many people and animals drowned in the swift, deep, shockingly cold water of the Platte.

From what’s now central Nebraska to South Pass in west-central Wyoming, travelers to California, Oregon and Utah all took more or less one route. Most came up the south side of the Platte from Fort Kearney, crossed the South Platte where the river forks in western Nebraska and continued west up the south side of the north fork. This meant fording the Laramie River where it joined the North Platte at Fort Laramie, and finally crossing the North Platte itself 150 miles later where the river bent to the south near present Casper. After that, the travelers could continue on to the west.

During fur-trade times in the 1820s and 1830s, many travelers crossed at Red Buttes, west of present Casper. In the early and mid-1840s, wagon-train emigrants began crossing at a variety of places along 25 miles of river from the mouth of Deer Creek, at present-day Glenrock, Wyo., to Casper.

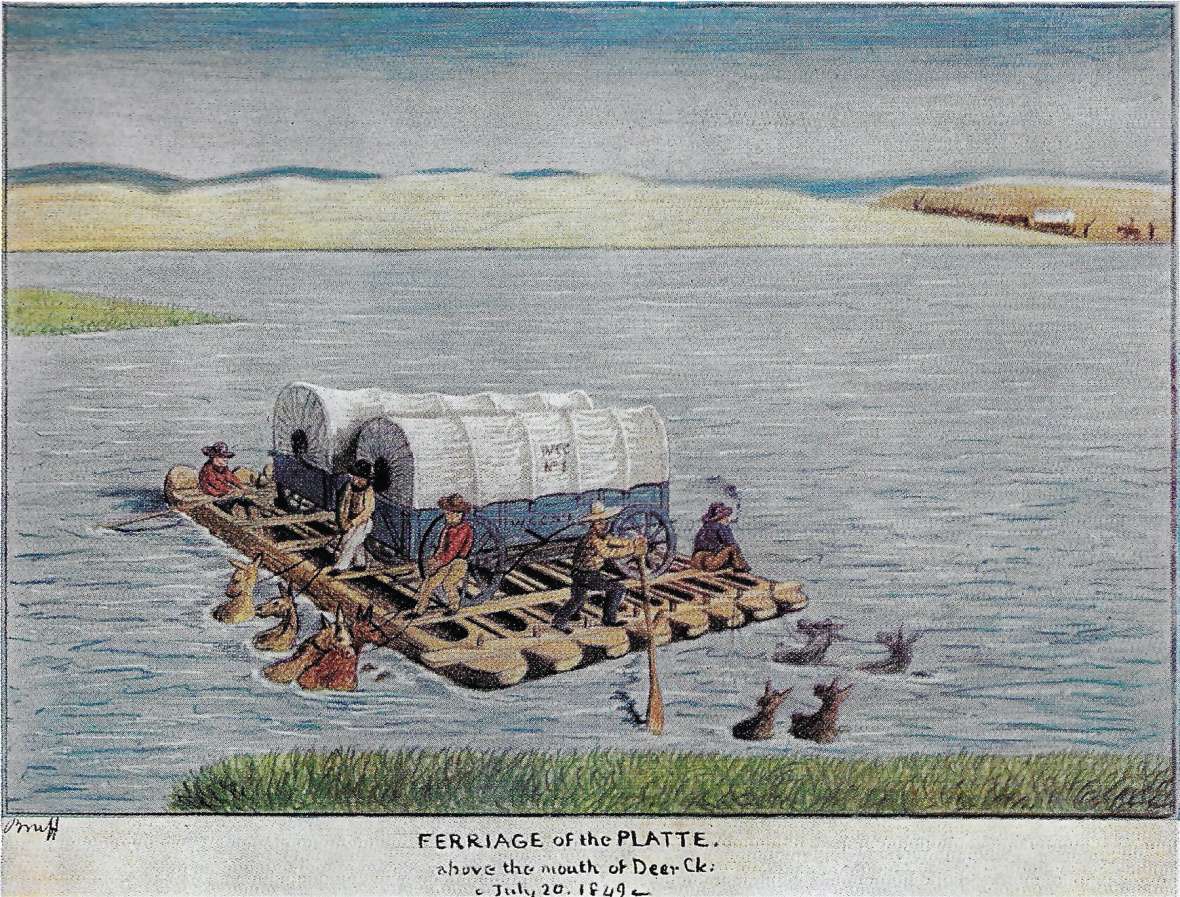

Many made small boats by emptying their wagons, removing the wagon box from the running gear, caulking the boxes water tight with tar, dismantling the running gear into pieces, and then ferrying everything across the water in the wagon boxes, using poles or oars for guidance and often using ox or human power to tow the craft across the water with long ropes. This was a fairly reliable method, but, due to the unloading, dismantling and reloading, very slow.

Big cottonwood trees were plentiful; some of the earliest travelers made simple rafts of cottonwood logs lashed together, which they poled or rowed across. These were unwieldy and dangerous. Soon, emigrants figured out how to hollow out cottonwood logs and make dugout canoes, 20 feet long or more. By lashing three canoes together, or lashing a canoe on either side of a log in the middle, emigrants found they could make a stable boat of the right width so that a wagon’s wheels could rest inside the two outermost canoes.

The Mormon ferry

In mid June 1847, the first Mormon pioneer party, bound for the Salt Lake Valley, experimented with wagon-box boats and rafts before building a stout ferry out of cottonwood dugouts and a pine-pole deck. Even Church President Brigham Young “stript himself and went to work with all his strength,” wrote diarist Thomas Bullock.

As they were finishing up, they found 108 wagons from other parties, stretched over four miles and “all wanting to cross the river,” Mormon diarist Norton Jacob wrote.

A practical solution suggested itself. Ten Mormon men stayed behind to run the ferry for the rest of the emigration season. They were directed to charge non-Mormons $3 cash or $1.50 worth of flour or other provisions at Iowa or Missouri prices to cross a wagon and family. The men were “to keep a Just & accurate account, & make the returns of the proceeds of their labor to the Authoritys of the Church & also to cross the Brethren”—that is, the Mormon emigrants expected to arrive later in the summer—“ & charge such as are able to pay a reasonable price to be determined by the council that shall come with the Camp,” Jacob noted.

This Mormon Ferry, as it came to be known, was the first commercial ferry at the upper crossing of the Platte, operating about where the bridge on Wyoming Boulevard crosses now between Casper and its suburb of Mills, Wyo.

All wagon trains traveled with a large number of animals. Loaded wagons moved best when pulled by three yoke of oxen: Six animals per wagon meant a train of 25 wagons needed daily grass and water for 150 cattle, plus any other mules, saddle horses or milk cows making the trip. Moving the animals across the river proved to be the trickiest part of all.

The Platte at its upper crossings, then and now, was 100 to 200 yards wide and more than 10 feet deep at its deepest point. Transcontinental emigrants who were on schedule crossed in June, when the water, at its height from spring runoff, was moving smooth and fast.

Because ferries charged a fee for each animal as well as for wagons, there was a strong incentive for emigrants to swim their livestock across. Account after account tells of one or two brave men in the party on horse- or muleback leading the herd into the water. At the point where the river gets deep enough that the animal has to swim, the person does as well, often without warning. Time and again travelers in their diaries tell of animals plunging in, trying to cross, losing their footing and being driven half a mile or more downstream only to emerge on the same side. The work exhausted the crossers and drownings were common every June. And stock died by the hundreds.

The gold rush

The Mormons again ran a ferry in 1848. In 1849, the first year of the California gold rush, they set up a blacksmith operation as well. Traffic mushroomed from a few thousand in 1848 to 25,000 in 1849, according to trails historian John Unruh. Diarists reported big crowds in June 1849, with waits of two or three days before they could cross.

Emigrants had to drive their animals miles away to find good grass, and then had to guard them while they grazed. Impatience and indifference is everywhere in the accounts. “[W]e found 150 wagons in ahead of us, about 50 can be crossed in a day,” William Thomas wrote on June 10. “Just before we arrived a young man by the name of Brown from Mo. was drowned attempting to swim his cattle across - This accident appeared not in the least to produce more excitement than if he had been a dog although he was represented to be a young man of fine abilities and esteemed by all who knew him …”

By this time the Mormons had a plank deck on their three-dugout ferryboat, on which they could cross 50 to 75 wagons per day. Finding 200 wagons waiting to cross on June 10, diarist David Pease tells of his company entering their name on the Mormons’ list, but then, impatient, choosing instead to work with two other companies to build a raft.

They had a bad time with it. Finally they persuaded the ferrymen to take one end of a rope across the river in order to tow the raft from the far shore, but “we soon found that the current was so swift and the rope bagged so much in the water that it was a difficult job to do anything and after crossing 2 wagons on [the raft] we gave it up as a bad job and concluded to wait patiently till our turn came on the boat.”

Hickman’s ferry

The following year, 1850, saw another huge jump in traffic to around 50,000 emigrants, and also a big improvement in the ferry. A Missourian, David Hickman, appeared on the scene in May with a better idea. He and a few men anchored stout posts in each river bank, strung a strong rope between them and attached to it with pulleys a pair of shorter ropes, one linked to the bow and one to the stern of the ferryboat. By making the bow rope shorter, the boat crossed the stream at an angle to the current, and the current drove it across, “much better than steam on as rapid a stream as this foaming Platte,” wrote diarist Madison Moorman.

Hickman and his men built three of these boats and seem to have had them running all through June. The Mormons at this time were still running a single boat, but with a rope-and-pulley system similar to Hickman’s. At least one diarist mentions a fifth boat jointly owned by Hickman and the Mormons.

With three boats and a crossing time of only a few minutes, Hickman and his partners could now handle around 300 wagons per day. Emigrants now waited a day or less for their turn.

The price, however, had risen to $5 per wagon. The Missourians “are doing a ‘smashing’ business,” wrote diarist A.C. Morse. “The proprietor told me last night that he could make $20,000 as his own interest”—nearly $600,000 in today’s money—“and return to the States in October.” No need to prospect for gold in California, diarist after diarist noted, when it was possible to make that kind of money right here on the Platte.

Not everyone used the ferries, however. At likely spots all along the 25 miles between the mouth of Deer Creek and the upper ferries, people made boats of their own, sold them to a party following them, who in turn would sell them for the same price to the next party behind them. All seem to have felt they were getting a fair deal.

The great majority of emigrants continued swimming their livestock across the river—and the practice remained dangerous. “[T]wo men were drowned yesterday & it is said 19 have been drowned in the last 11 days,” Francis Hardy noted from the upper ferry June 10, 1850.

Wagon companies would often search a day or even two for the bodies, but felt compelled after that to resume their trek. Emigrants traveling to California with Finley McDiarmid saw the body of a drowned man caught in the branches of a dead tree in the river. “One of the men swam out and towed him in,” McDiarmid wrote. “There was nothing about his person that could give any information where he was from or who he was. They buried him the usual way of burying people upon this road by digging a shallow small hole [italics in original] and rolling him in.”

The bridges

Reports of cholera led to a drastic reduction in trail traffic in 1851, and prices fell accordingly, to $2.50 and $3.00 per wagon at the upper Platte ferries. In 1852, the number of westbound travelers who came over the trail in what’s now Wyoming boomed again, peaking at 70,000 that year. In May, some emigrants built a bridge over the North Platte at the mouth of Deer Creek. High water washed it away after a few weeks, however.

That fall, the enterprising trader John Baptiste Richard and his partners began building a bridge at a well-known crossing site at what is now Evansville, just east of Casper and eight or so miles east of the Mormon ferry. Because of how Richard pronounced his name, English-speaking travelers misunderstood it as Reshaw; the bridge came to be called Reshaw’s Bridge. It was built on log tiers 30 to 40 feet apart, in a diamond shape with the points aimed up and down river, filled with rocks and decked with planks. The bridge was finished in time for the start of emigration in spring 1853.

That fall, the enterprising trader John Baptiste Richard and his partners began building a bridge at a well-known crossing site at what is now Evansville, just east of Casper and eight or so miles east of the Mormon ferry. Because of how Richard pronounced his name, English-speaking travelers misunderstood it as Reshaw; the bridge came to be called Reshaw’s Bridge. It was built on log tiers 30 to 40 feet apart, in a diamond shape with the points aimed up and down river, filled with rocks and decked with planks. The bridge was finished in time for the start of emigration in spring 1853.

Richard established a trading post at the bridge. His prices were high—$8 to cross a wagon at high water, falling to $6 by early July. The U.S. Army established a post at the bridge in 1855, when tension was mounting between emigrants and Native Americans.

As the population in the 1850s grew in the far West and in the Salt Lake Valley, traffic on the Platte River route became more commercial and more two-way, with freighters heading east almost as often as west. A once-a-month stagecoach was established from Missouri to Salt Lake in the late 1850s; gradually the service became weekly and eventually daily.

Richard and his brothers had a prime business spot, and for a few years they prospered.

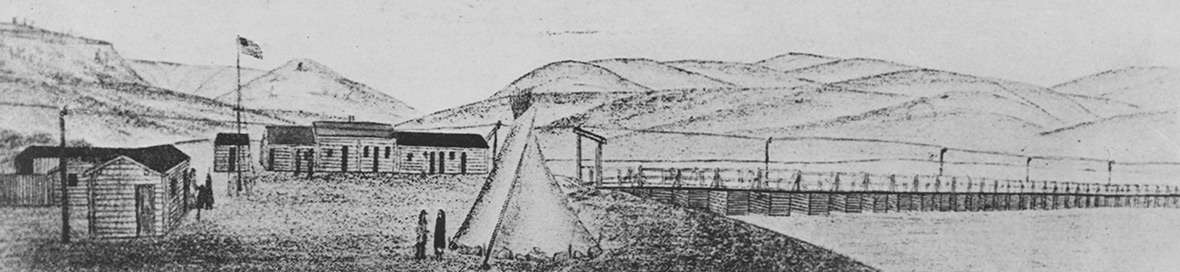

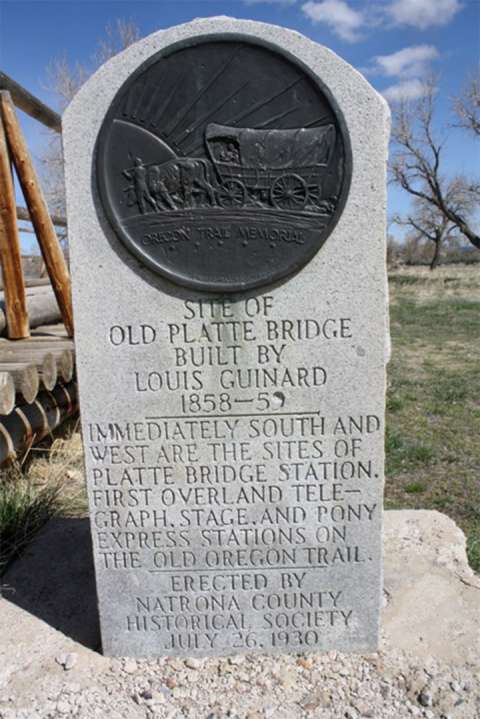

Beginning in the fall of 1859, a former Richard partner, Louis Guinard, built a much larger, stronger bridge—1,000 feet long, on 26 piers—just upstream from the upper ferry crossings. One account says he spent $40,000 on the bridge; another says $60,000. The bridge was finished in time for the 1860 season. One traveler in 1861 reported tolls of $3 per wagon; possibly competition between the two bridges kept prices low.

Guinard also ran a trading post at the bridge. The stages carrying the U.S. Mail used Guinard’s bridge—a blow to Richard’s business—and in 1860 and 1861 the short-lived Pony Express did as well, and established a station there.

In 1862, the Army established a post at Guinard’s Bridge named Platte Bridge Station. After young Lt. Caspar Collins was killed in an Indian fight nearby in 1865—the Battle of Platte Bridge Station—the fort was renamed for him.

Richard, meanwhile, had left the area, though his employees continued to run his bridge. In the winter of 1865-1866, soldiers from the fort upstream dismantled Richard’s bridge and his trading houses for firewood and building materials. In 1867, Fort Fetterman was built near present Douglas, Wyo., 50 miles down the Platte, and Fort Casper was partly dismantled for wood for the new fort. In 1869, the Union Pacific Railroad was completed across what’s now southern Wyoming, and most people stopped using the Platte River road as a transcontinental route.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Berrien, Joseph Waring. “Overland from St. Louis to the California Gold Fields in 1849: The diary of Joseph Waring Berrien.” Ed. by Ted and Caryl Hinckley. Indiana Magazine of History (December 1960): 273-352.

- Bullock, Thomas. The Pioneer Camp of the Saints: The 1846 and 1847 Mormon Trail Journals of Thomas Bullock. Ed. by Will Bagley. Spokane, Wash.: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1997.

- Burton, Richard F. The City of the Saints and across the Rocky Mountains to California [1860]. London,1861. New York,1862. Reprinted as The Look of the West, Overland to California, Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1963.

- Butterfield, Ira H. “Michigan to California in 1861.” Michigan History Magazine 11, no. 40 (July 1927): 392–423.

- Hardy, Francis A. Journal of Francis A. Hardy, 1850. WA MS 242, Beinecke Library. Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Richard L. Rieck transcription.

- Jacob, Norton. The Mormon Vanguard Brigade of 1847: Norton Jacob’s Record. Ed. by Ronald O. Barney. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 2005.

- Judson, Henry M. Diary, 1862. MS 953, Typescript. Nebraska State Historical Society.

- Kelly, William. An Excursion to California over the Prairie, Rocky Mountains, and Great Sierra Nevada. 2 vols. London, UK: Chapman and Hall, 1851.

- May, Richard Martin. A Sketch of a Migrating Family to California in 1848. Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, 1991.

- McDiarmid, Finley. Letters to My Wife [1850]. Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, 1997.

- Pease, David E. Diary, 1849. MS 60, Typescript. Oregon Historical Society Library, Portland, Ore.

- Root, Riley. Journals of Travels from St. Joseph to Oregon. Galesburg, Ill., Gazeteer and Intelligencer, 1850. Reprint, Oakland, Calif.: Biobooks, 1955.

- Thomas, Dr. William L. Diary. MS CB 383:1, Typescript. Bancroft Library, Berkley, Calif.

- Winsor, Alonzo, Diary. Typescript of the original MS, Newberry Library, Chicago. Richard L. Rieck transcription.

Secondary Sources

- Brown, Randy. Oregon-California Trails Association. WyoHistory.org offers special thanks to this historian for providing the diary entries used in this article.

- Glass, Jefferson. “Reshaw’s Bridge.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed April 16, 2016, at /encyclopedia/reshaws-bridge.

- National Park Service. National Historic Trails: Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide Across Wyoming. Salt Lake City: National Park Service, National Trails System, Intermountain Region, 2007, 52. Accessed March 23, 2016, at http://www.nps.gov/cali/planyourvisit/upload/WY_ATRIG%20Web.pdf.

- “Upper Platte (Mormon) Ferry. Church History, website of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Accessed April 21, 2016 at https://history.lds.org/place/pioneer-story-upper-platte-mormon-ferry?lang=eng.

- Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. “Platte River Fords.” Emigrant Trails Throughout Wyoming. Accessed March 23, 2016, at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/trailsdemo/platteriverfords.htm.

- Unruh, John D. The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1860. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1979, 119-120, 185. Accessed March 23, 2016, at http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/ows/seminarsflvs/UnruhTables.pdf.

Illustrations

- The image of the Bruff drawing of the 1849 ferry is from Randy Brown. Used with thanks. Bugler Moellman’s drawing of Platte Bridge Station, 1863, is from the American Heritage Center. Used with permission and thanks. The rest of the photos are by WyoHistory.org Editor Tom Rea.