- Home

- Encyclopedia

- A Map of The West In His Head: Jim Bridger, Gui...

A Map of the West in his Head: Jim Bridger, Guide to Plains and Mountains

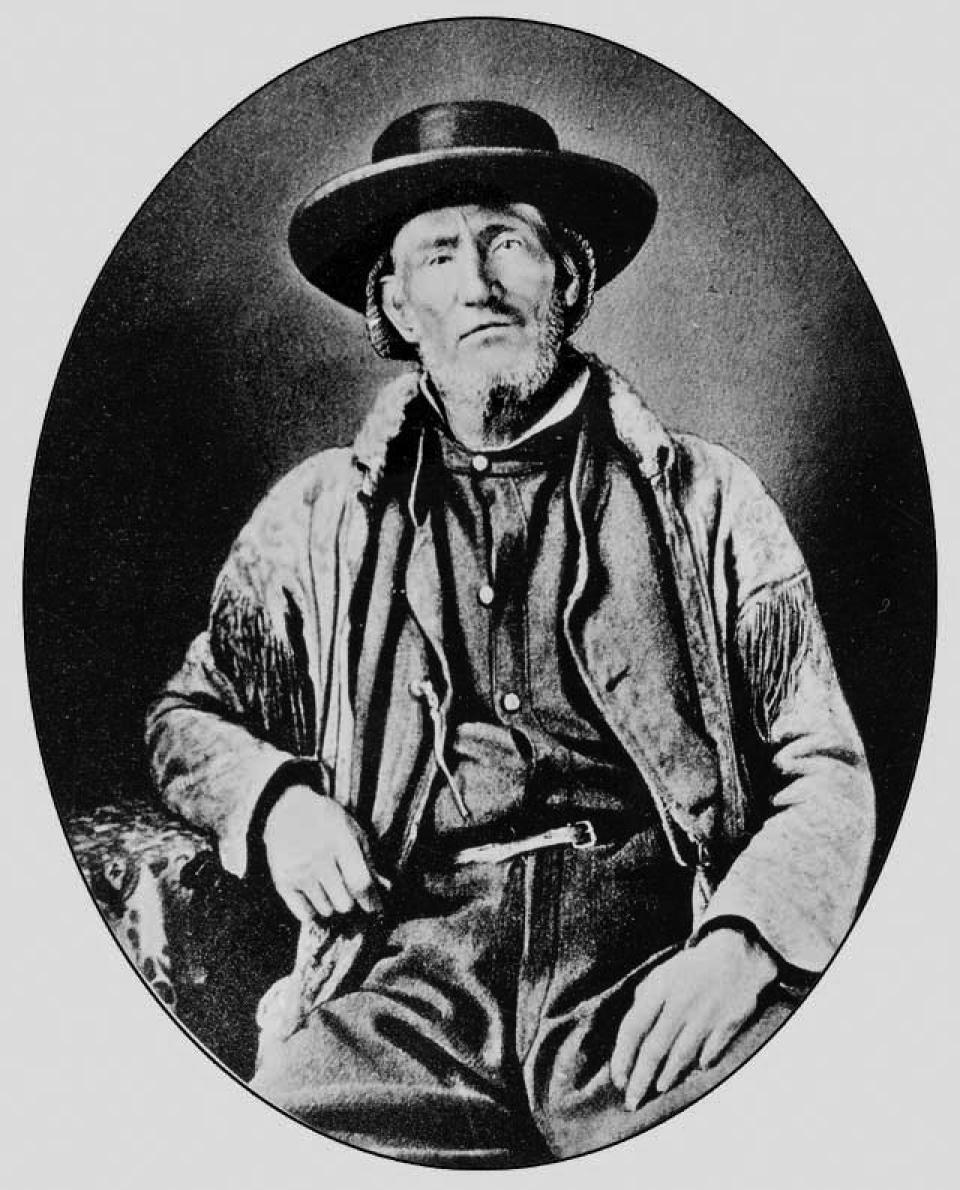

Jim Bridger already had more than 30 years experience in the West as a trapper, mountain man and Indian fighter before he became the premier guide for the U.S. Army in the mid-1850s.

Image

In 1822, at 17, Bridger enlisted in the Ashley-Henry expedition sent from St. Louis to trap beaver in the Rocky Mountains. He worked first as an employee and later became a partner in the famous Rocky Mountain Fur Company. He mastered wilderness lore and accumulated an astounding mental map of western North America when nearly all of it was still unsettled by whites.

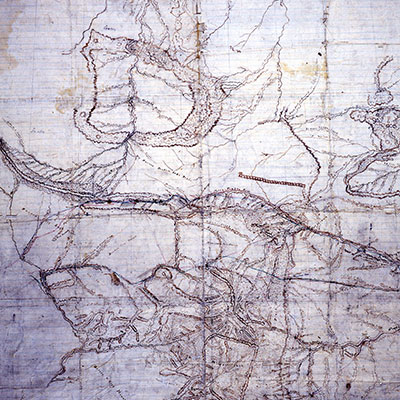

It was this geographical knowledge that aided many U. S. Army Topographical expeditions to successfully complete assignments. Bridger provided from memory accurate maps of the Rocky Mountains to U. S. military commanders leading exploratory expeditions. He possessed an intimate knowledge of western geography and natural transportation routes.

Bridger was also well known among the American Indian tribes of the Rockies, especially the Shoshone. He was a personal friend of Shoshone Chief Washakie and was married three times to native women: a Flathead, a Ute, and Shoshone. As a result of all his experience, Bridger played an integral role in the initial geographical discoveries in the West, which, in turn, helped foster early Euro-American emigration and settlement.

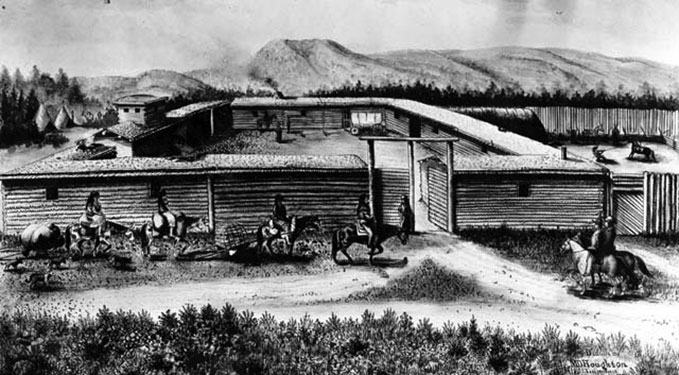

Bridger's experience had few limits. He quit the dying fur trade in 1842 and in 1843, with his partner Louis Vasquez, established a trading post along the Blacks Fork of the Green River in what is now Wyoming and in what then was still a corner of Mexico. Bridger recognized that the overland migration to Oregon was a sign of changing settlement patterns, and that Fort Bridger could not help but become a profitable economic concern. For the next fifteen years, the post was a key supply point for Oregon/Mormon/California Trail emigrants needing provisions, livestock, and wagon repairs.

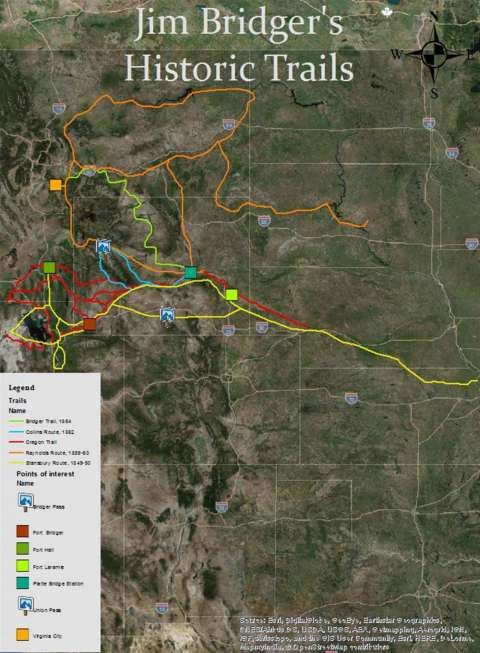

The Stansbury expedition to the Great Salt Lake in 1849-1850 was the first federally funded government exploration guided by Bridger. It was designed to acquire geographical and geological data about the West that would facilitate a future route for a transcontinental railroad and telegraph and to locate coal deposits. On the return, Bridger guided Stansbury's party east along ways that later became familiar as the Overland Trail and Union Pacific Railroad routes.

Bridger's unequaled knowledge of the northern Rocky Mountain region and upper Missouri River Basin aided two expeditions searching for transportation routes between 1856 and 1860. He served as guide for Lt. Gouverneur K. Warren's 1856 expedition to reconnoiter the regions surrounding the Black Hills and the Yellowstone River. He led Warren's party from Fort Union, at the mouth of the Yellowstone on the Missouri near the present Montana-North Dakota border, southwest up the Yellowstone to the mouth of Powder River. Warren's explorations revealed a great deal of geographical information that was still lacking to Euro-Americans. In his reports on the Dakota region, Warren recommended further reconnaissance of the upper Yellowstone and Powder River country, regions that were still classified as terra incognita.

As a result, Captain William Raynolds was ordered to explore the region in 1859. Bridger was the logical choice to guide this important expedition as well. When the Army resumed operations against the Sioux after the Civil War, the Warren and Raynolds reports formed the only existing body of information pertaining to the Dakota-Wyoming region.

Whenever the mission was important, the government's choice was invariably the same: Jim Bridger. Among other expeditions, he spent part of the year 1857 guiding Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, who was sent with 2500 troops to escort the new federal governor and restore the presence of the U.S. government in Utah Territory during the bloodless Utah (Mormon) War.

Bridger served in 1861 as guide for an exploratory party under the command of Capt. E. L. Berthoud searching for a route through the Colorado Rockies, and in 1862 he served under Col. William Collins and his son Lt. Caspar Collins on an expedition west up the Sweetwater, over South Pass, around the west side of the Wind River Mountains and back east over Union Pass.

Bridger achieved the rank of major and was the chief guide (at $10 a day) assigned Fort Laramie through the remainder of the 1860s until his retirement late in 1868. In 1864, however, he spent the season guiding emigrant trains to Montana Territory, after obtaining a leave of absence from the fort on April 30. On May 20, he began guiding the first train of emigrants along the Bridger Trail through the Bighorn Basin to the Montana gold fields near Virginia City. He led a second party along the trail in the fall.

Cheyenne. and Lakota Sioux opposition to emigration and military activity along the Bozeman Trail intensified in 1865 and Bridger's services as guide were needed more than ever. He guided the lead column of the U.S. Army's Powder River Expedition, under the command of Gen. Patrick E. Connor, which was ordered into the Powder River Basin to find and punish the Lakota and their allies. The campaign failed in its attempt to curtail Indian aggression along the Bozeman Trail.

Bridger served his last commission in 1868 following the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty, which closed the Bozeman Trail and the forts built in vain to defend it. He guided the Army to the Powder River Basin to remove the property from the forts. When he returned, he was paid and discharged from the Army at Fort D.A. Russell, near Cheyenne. He retired to his farm in Westport, near Kansas City, Mo., and died on July 17, 1881 at the age of 77.

Gen. Grenville M. Dodge served in the Civil War and later commanded the Department of the Missouri before going to work in 1866 as Chief Engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad. Bridger guided Dodge on railroad surveys and Indian campaigns. “Unquestionably Bridger’s claims to remembrance,” Dodge wrote 40 years later,

rest upon the extraordinary part he bore in the explorations of the West. As a guide he was without equal, and this is the testimony of everyone who ever knew him. He was a born topographer; the whole West was mapped out in his mind, and such was his instinctive sense of locality and direction that it used to be said of him that he could smell his way where he could not see it. He was a complete master of plains and woodcraft, equal to any emergency, full of resources to overcome any obstacles, and I came to learn gradually how it was that for months such men could live without food except what the country afforded in that wild region. … Bridger was not an educated man, still any country that he had ever seen he could fully and intelligently describe, and he could make a very correct estimate of the country surrounding it. He could make a map of any country he had ever traveled over, mark out its streams and mountains and the obstacles in it correctly, so that there was no trouble in following it and fully understanding it. … He understood thoroughly the Indian character, their peculiarities and superstitions. … As a guide I do not think he had his equal upon the plains.

In 1904, on the 100th anniversary of Bridger's birth, Dodge had Bridger’s remains reinterred at a select spot in the Mount Washington Cemetery in Independence, Missouri, with a 7-foot monument depicting Bridger's principal achievements:

"Celebrated as a hunter, trapper, fur trader and guide. Discovered Great Salt Lake 1824, the South Pass [1823]. Visited Yellowstone Lake and Geysers 1830. Founded Fort Bridger 1843. Opened Overland Route by Bridger's Pass to Great Salt Lake. Was a guide for U. S. exploring expeditions, Albert Sidney Johnston's army in 1857, and G. M. Dodge in U. P. surveys and Indian campaigns 1865-66."

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article was published originally at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/btrail/jimbridger.html as part of “The Bridger Trail,” an extensive website on the subject published by the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office with support from Burlington Resources. Used here with permission and thanks.

Resources

- Dodge, Grenville M. Biographical Sketch of Jim Bridger, Mountaineer, Trapper and Guide. New York: Unz and Company, 1905. Accessed 9/17/14 at https://archive.org/stream/biographicalsket00dodg#page/n3/mode/2up.

- Honig, Louis O. James Bridger, The Pathfinder of the West. Kansas City, Mo.: Brown-White-Lowell Press, 1951.

- Lowe, James A. The Bridger Trail: a viable alternative to the gold fields of Montana Territory in 1864, with excerpts from emigrant diaries, letters, and comparative material from Oregon and Bozeman Trail diaries. Spokane, Wash: Arthur H. Clark Co, 1999.

Illustrations

- Col. William Collins’ hand-drawn version of Bridger’s map of large parts of what are now Montana, Wyoming and Colorado is in the collections of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. According to AHC records, Bridger first drew a version in the dirt with a stick, and a second with charcoal on animal skin. Collins drew this copy, gave it to his son Caspar Collins, who gave it to Rawlins-area pioneer and longtime newspaperman John Friend. Friend gave it to Grace Raymond Hebard, librarian, trustee, historian and professor at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks. The AHC offers copies of this map for sale. For more information, contact the reference department at ahcref@uwyo.edu or 307-766-3756.

- The Jim Bridger portrait is also from the AHC, by way of the SHPO website. Used with permission and thanks.