- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Yellowstone, The World’s Wonderland

Yellowstone, the World’s Wonderland

Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first national park, was established in 1872 and continues to enthrall visitors who flock to see its striking scenery, topography, plentiful wildlife and amazing thermal features. The name derives from the French Roche Jaune –yellow stone—for the large tributary that joins the Missouri River near the present Montana-North Dakota line.

The Yellowstone name was already in general use among fur traders and trappers when Lewis and Clark encountered them at the Mandan villages in 1804-05, yellow being the color of unknown rock walls somewhere along the lower river—perhaps the rimrock at present Billings, Mont.

The park is located on the river’s headwaters in the northwestern corner of Wyoming (96%), southwestern Montana (3%) and eastern Idaho (1%). In Wyoming, the park is divided between Park and Teton counties. Larger than the combined states of Rhode Island and Delaware, its area covers more than 2.2 million acres, nearly 3,500 square miles. It is 63 miles long north to south and 54 miles wide.

As the center of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the park is surrounded by wilderness areas, two national wildlife refuges, and five national forests. The first national forest in the United States, the Shoshone, set aside in 1891 as part of the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, borders Yellowstone on the east. Other forests include the Gallatin, Caribou-Targhee, Bridger-Teton and Custer. The John D. Rockefeller Memorial Parkway connects Yellowstone with Grand Teton National Park on the south. The headwaters of several major western rivers flow from the mountains in the Greater Yellowstone area including the Yellowstone, Green, Snake, Madison, Firehole, Gallatin, Gardner, Gibbon, Lamar, Lewis and Bechler.

Early inhabitants

Evidence of human occupation of the Yellowstone Plateau dates back approximately 11,000 years. A Clovis projectile point was uncovered near the north entrance during the construction of the Gardiner, Mont. post office. To the south, in the Bridger-Teton National Forest, a Folsom point made of obsidian taken from Yellowstone’s Obsidian Cliff dates to 10,000 years ago. A few miles east of the park, near the Shoshone River, Mummy Cave was excavated in the 1960s. That site shows evidence of continual habitation back to 7280 B.C. and counters an earlier belief that the early inhabitants feared the geysers and stayed away from the area.

Recent ethnographic research by Peter Nabokov and Lawrence Loendorf reveals that most of the tribal groups associated with areas bordering Yellowstone did indeed travel through the area and made use of natural resources found there. The Blue Camas is one of many food sources found in the Yellowstone ecosystem. Fields of this purple-flowering plant with edible root were highly sought after and protected by the tribes who knew of their existence. One such field is located west of Yellowstone Lake.

At least 26 American Indian tribes are associated with Yellowstone National Park, among them Crow, Kiowa, Blackfeet, Nez Perce, Shoshone, Sheep Eater and Bannock. Individuals consulted during the ethnographic study previously mentioned, revealed native place names for geographic features Euroamericans know today as Heart Mountain, Sunlight Basin and the Shoshone River. Such familiarity with the terrain of the region supports the conclusion that these various groups did indeed travel through and reside within the ecosystem.

There are more than 1,600 identified archaeological sites and more than 300 ethnographic resources within its borders. For example, the Nez Perce National Historic Trail passes through Yellowstone and commemorates the 1877 flight of the Nez Perce from their homeland to Canada. As they were pursued by U.S. troops under generals Howard, Sturgis and Miles, their route crossed the northern portion of the park, exiting Wyoming near the Clark’s Fork River.

Exploration and discovery

Rumors of an area in the Rocky Mountains rich in such unbelievable wonders as boiling and spouting springs and mud pools, mountains of glass and petrified forests, and an unusually colored canyon with astonishing waterfalls were shared among early fur trappers and explorers. Assumed to be tall tales, even the exaggerated stories related by Jim Bridger contained elements of truth that were later verified by scientific expeditions.

As part of the exploration of the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark followed the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, but did not trace either to their headwaters and so missed the geyser basins along the Firehole River or the travertine terraces of Mammoth Hot Springs. However, John Colter, a member of the Corps of Discovery who left the group before its return to St. Louis, is credited with discovering the Yellowstone region.

It is impossible to know Colter’s exact route, but it is generally believed he visited the area near present Cody, Wyo., viewing the hot springs there along the banks of the Shoshone or Stinking Water River. Fur-trade and Yellowstone historian Hiram Chittenden explained that upon Colter’s return to St. Louis in 1810, he described his route to William Clark who incorporated it in the map of the expedition and noted it as “Colter’s Route in 1807.”

Daniel Potts, a fur trapper who in 1826 visited the area known today as the West Thumb Geyser Basin on the southwest side of Yellowstone Lake, supplied the earliest documented description of a part of the Yellowstone region. In a letter to his brother published in a Philadelphia newspaper the next year, he described the geysers and hot springs viewed there as well as the Green, Shoshone, Madison and Gallatin Rivers. Other trappers likely to have visited the area include Joe Meek, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger and Osborne Russell.

The first tourist to visit the area of the park, according to Yellowstone historian Aubrey Haines, was Warren Angus Ferris, a clerk for the American Fur Company. Overhearing fur trappers talking about remarkable features along the Firehole River, Ferris decided to see for himself and visited the geyser basins in the spring of 1834. Chittenden stated that Ferris holds the honor of having written the first actual description of the geyser basins. Ferris kept a journal and, on his return from the frontier, published it in the Western Literary Messenger of Buffalo, N.Y.

In April 1859, Capt. W. F. Raynolds, U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers, received orders to explore “the region of country through which flow the principal tributaries of the Yellowstone River, and the mountains in which they, and the Gallatin and Madison Forks of the Missouri, have their source.” The geologist assigned to accompany Raynolds was Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden. Mountain man Jim Bridger, familiar with the region, was employed as guide.

As the first government expedition assigned the responsibility of exploring the heart of the Yellowstone region, it is noted for Hayden’s participation as well as the geographical knowledge shared through Raynolds’ report and the accompanying map. However, deep snow still on the ground in June prevented the party from penetrating any of the country that now makes up the park.

A decade later a group of Montana residents decided to visit the remarkable region. Departing Diamond City on the Missouri River near Helena, Montana Territory on Sept. 6, 1869, David E. Folsom, Charles W. Cook and William Peterson followed the river to the Gallatin Valley and on to Bozeman and Fort Ellis. They reached the park region on Sept. 13, 1869. During a 36-day tour, they saw many of the features that are now landmarks.

Their effort was followed in 1870 by the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition. Henry Dana Washburn was the Surveyor-General for Montana Territory. Folsom, working in the same office, had shared with Washburn the geographical knowledge of his earlier exploration.

The Washburn Expedition followed the approximate route of its predecessor but is credited with naming the famous geyser Old Faithful, for its supposed regularity—though other geysers are more regular. One member of the Washburn party, Truman Everts, became separated from the main group and spent 37 days lost in the Yellowstone.

Observing the natural phenomena about them and keeping records, members of the party produced maps of the areas they visited. Their observations led to increased curiosity among scientists and geographers.

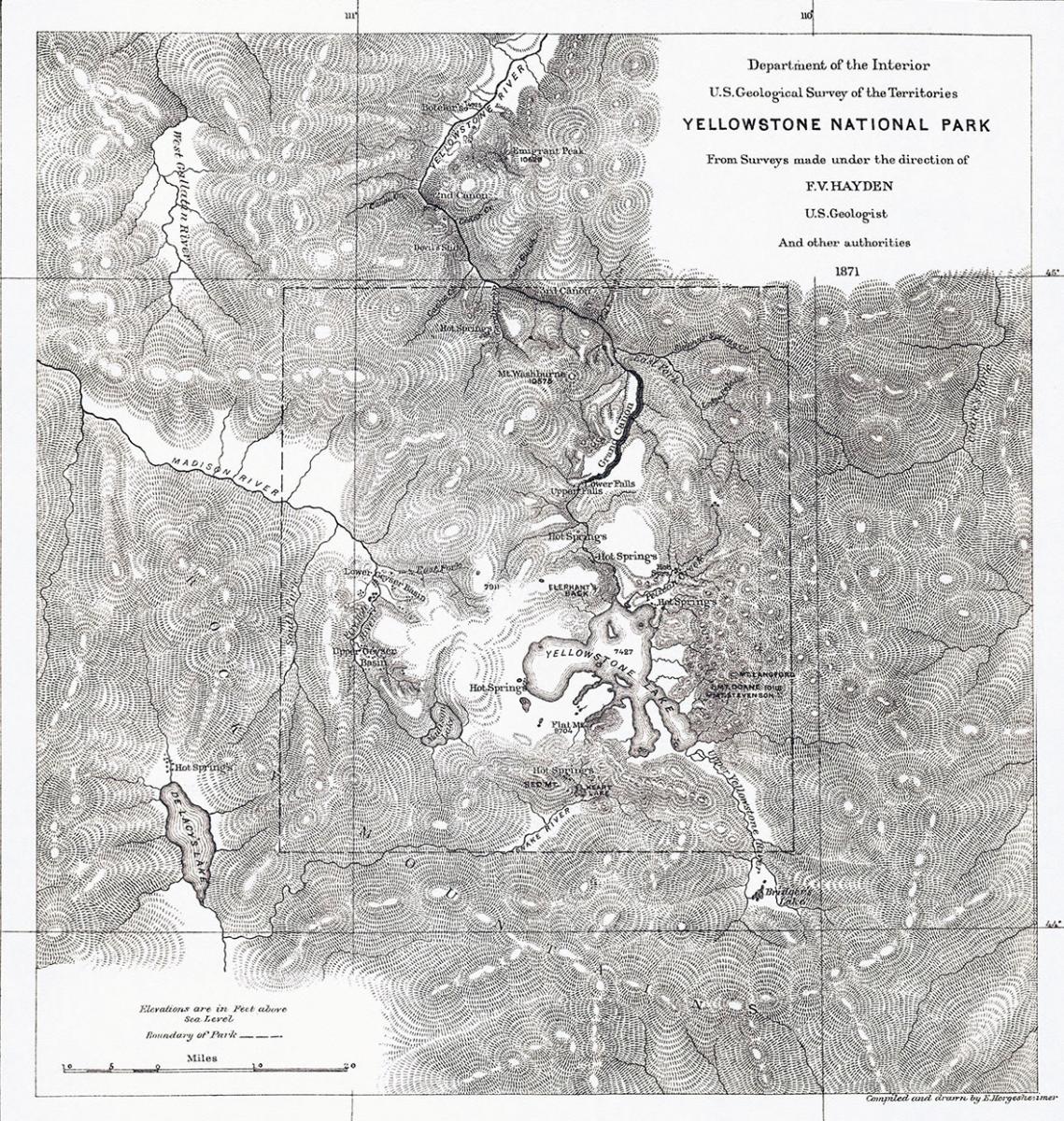

The following year, two official government expeditions were organized to explore and document the region. Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden was appointed U.S. geologist and instructed to provide an accurate geographical map of the region explored. The Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads agreed to carry men and equipment west at no charge. James Stevenson, Hayden’s assistant, outfitted the party at Fort D. A. Russell near present-day Cheyenne, Wyo. Photographer William Henry Jackson and artist Thomas Moran accompanied Hayden.

The second government party, led by Capt. John W. Barlow and David P. Heap of the Department of Dakota Engineer Office, was assigned the topographical work. A smaller contingent, they shared the military escort with Hayden. Photographer Thomas J. Hine joined Barlow and Heap. His pictures of the wonders of the Yellowstone region would have added immensely to the photographic record created by Jackson—had Hine’s negatives survived the great Chicago fire.

The headquarters of the Military Division of the Missouri, including most of the results of the Barlow and Heap Expedition, were destroyed by that conflagration, in October 1871. Barlow wrote Hayden, “Not one single paper or other property was saved from my office. All my instruments, maps, books, and everything brought back from the Yellowstone, including specimens were consumed. I have to begin anew.” Sixteen photographic plates belonging to Hine were saved only because he had taken them home. He had hoped to produce 200 images. As a result, the reports, maps, photographs and paintings by Hayden’s party provided the only evidence verifying the wonders of Yellowstone.

The world’s first national park

As the West opened to Euroamerican settlement in the 19th century, concerns began to arise about how the land and resources would be managed. Early attempts to preserve outstanding resources set aside Niagara Falls; Hot Springs, Ark., and in 1864, the Yosemite Grant. As settlement encroached on Niagara Falls and destroyed its pristine setting, some Americans began to see a need for protection of such special places.

With the various explorations verifying the phenomena of the Yellowstone wonderland, some of the explorers claimed the national park idea as their own. One tradition, which lasted nearly a century, is the so-called “campfire story.” Members of the Washburn-Langford-Doane expedition gathered around a campfire near the junction of the Firehole and Madison rivers and discussed how this region should be used. It was here they claimed to have the foresight to set aside the region as a national park rather than land to be used for personal gain.

In 2003, Yellowstone historians Lee Whittlesey and Paul Schullery published their research on the persistence of this myth, showing how the campfire story was promoted through several generations by conservationists, historians and employees of the National Park Service.

Publicizing the wonders and spectacles of the region fell to expedition members such as Hayden, Moran, Jackson and Langford. Hayden wrote, “The official report of this expedition, published after the return of the party in the autumn of 1871, created so great an interest among the people that in February 1872, Congress was induced to pass an act” withdrawing an area of about 3,500 square miles from settlement and establishing “a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” President Ulysses S. Grant signed the act March 1, 1872, establishing Yellowstone National Park.

A public lands management experiment

From the creation of the park to the present, Yellowstone has served as a wilderness laboratory in nearly all aspects of its management. As the first national park, every element of its operation was essentially experimental. While Congress supported the creation of the national park, it failed for several years to appropriate funds for the protection and improvement of the reserve.

Nathaniel P. Langford was appointed the first superintendent, but Chittenden’s research revealed that Langford received no funds for the park. In 1877, Philetus W. Norris, considered to be one of the most important figures in Yellowstone’s history, succeeded Langford. Under Norris’s capable administration, Congress finally allocated the resources to make improvements and set the course for national parks in protection, visitor access and scientific management.

Early in Yellowstone’s history, the difficult, dual mission of protecting the resource while making it available to the public led to creation of the grand loop road, issuance of leases for providing tourist facilities, and protection of flora and fauna. At times, visitors provided the most destruction by killing wildlife, collecting souvenirs from the geothermal features and camping anywhere they pleased.

To aid in the protection, Secretary of the Interior L.Q.C. Lamar requested in 1886 that the U.S. Army take over park supervision. On Aug. 20, 1886, Capt. Moses Harris, Company M, 1st Cavalry, arrived in Yellowstone. The army oversaw the protection of resources, development of park roads and leases to concessionaires until administration was turned over to the newly created National Park Service in 1918.

The National Park Service was established Aug. 25, 1916, with the mandate “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Stephen T. Mather became the first director and Horace M. Albright served as his assistant. In 1919, Albright became the first National Park Service superintendent of Yellowstone. Both Mather and Albright had a passion for the national parks and set the course for public support of all parks.

Capitalism, conservation, culture

In a piece on Yellowstone published in Icons of the American West, Alexandra Kindell states “establishment of Yellowstone and the National Park system emerged as a means to bring income to a number of parties, especially Western railroads and the federal government. Thus capitalism, conservation, and culture combined to encourage Congress to start reserving lands for recreational purposes and to transform the Yellowstone area.”

Railroad companies, private enterprises and the federal government began transforming the Yellowstone wilderness into a tourist destination. Railroads built lines as close to park boundaries as possible and subsidized many of the operations, especially lodging. All three continue to impact the management of Yellowstone today.

With the advance of scientific wildlife management, changes came to Yellowstone. Bear feeding grounds, once the source of entertainment for thousands of visitors, were closed. Non-native species, introduced for the enjoyment of fishermen, are now deemed a nuisance and have resulted in the decimation of native trout. The extermination of a top-level predator, the wolf, led to an overabundance of elk. With the controversial reintroduction of the wolf to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in 1995, some of that balance has been restored.

All aspects of the conservation and preservation of the region contribute to evolving understanding of how best to manage the park. A decades-old policy of suppressing all fires was replaced in 1972 by a new one that allowed most naturally caused fires to burn. In 1988, a year of exceptionally dry and windy conditions, the park was swept by fires that, The Yellowstone Atlas notes, were attributed to this policy of limited fire suppression. Fires that year burned 1.1 million acres—more than all other years combined. It was not until snow fell in September that the embers died out.

Managing Yellowstone in the 21st century continues to provide insights in to the inter-relatedness of a large ecosystem—and people’s role in it. Visitors, meanwhile, continue to pour in; visitation peaked at 3.6 million people in 2010 and has fallen somewhat since, to 3.2 million in 2013. Culture, capitalism and conservation continue to impact Yellowstone, the crown jewel of the national parks.

Resources

Primary sources

- Chittenden, Hiram M. Annual Reports Upon the Construction, Repair, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899-1906.

- Raynolds, W. F. “Report of Captain W. F. Raynolds' Expedition to Explore the Headwaters of the Missouri & Yellowstone Rivers.” Washington, D.C.: 40th Congress, second session, 1867. This is Raynolds’ report from his 1859-69 expedition and contains an interesting, long paragraph on his failed attempts to reach the Yellowstone Plateau. Accessed April 28, 2014 at http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~familyinformation/fpk/raynolds_rpt.html#yellowstone.

Secondary sources

- Biddulph, Stephen G. Five Old Men of Yellowstone: The Rise of Interpretation in the First National Park. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2013.

- Chittenden, Hiram M. The Yellowstone National Park: Historical and Descriptive. Cincinnati, Ohio: The R. Clarke Co., 1895.

- __________. The Yellowstone National Park, Historical and Descriptive. 3d ed., rev..

- St. Paul, Minn.: J. E. Haynes, Publisher, 1927.

- Culpin, Mary Shivers. For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People: A History of Concession

- Development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1966. Yellowstone National Park, Wyo.:

- National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, 2003.

- Gowans, Fred R. A Fur Trade History of Yellowstone Park: Notes, Documents, Maps.

- Orem, Utah: Mountain Grizzly Publications, 1989.

- Haines, Aubrey L. The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park. 2 vols.

- Yellowstone National Park, Wyo.: Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, 1977.

- _________ . Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment.

- Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, 1974.

- Johnson, Jerry, ed. Knowing Yellowstone: Science in America’s First National Park.

- Lanham: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2010.

- Kindell, Alexandra. “Yellowstone National Park.” In Icons of the American West: From Cowgirls to Silicon Valley. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2008.

- Marcus, W. Andrew, James E. Meacham, and Ann W. Rodman. 2012. Atlas of Yellowstone. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

- Nabokov, Peter and Lawrence Loendorf. Restoring a Presence: American Indians and Yellowstone National Park. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

- Rubinstein, Paul, Lee H. Whittlesey and Mike Stevens. The Guide to Yellowstone Waterfalls and Their Discovery. Englewood, Colo.: Westcliffe Publishers, 2000.

- Rydell, Kiki Leigh and Mary Shivers Culpin. Managing the “Matchless Wonders:” A History of Administrative Development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1965. Yellowstone National

- Park, Wyo.: National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, 2006.

- Runte, Alfred. National Parks: The American Experience. 4th Edition. Lanham, Md.: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2010.

- Schullery, Paul. Searching for Yellowstone: Ecology and Wonder in the Last Wilderness.

- Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

- Schullery, Paul and Lee H. Whittlesey. Myth and History in the Creation of Yellowstone National Park. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- Sellars, Richard West. Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. New Haven, Conn.:

- Yale University Press, 1997.

- Watry, Elizabeth A. Women in Wonderland: Lives, Legends and Legacies of Yellowstone National Park. Helena, Mont.: Riverbend Publishing, 2012.

- Whittlesey, Lee H. A Yellowstone Album: A Photographic Celebration of the First National Park. Boulder, Colo.: Roberts Rinehart: American Gramophone in Cooperation with the Yellowstone Foundation, 1997.

- __________. Wonderland Nomenclature: A History of the Place Names of Yellowstone National Park: Being a Description of and Guidebook to its Most Important Natural Features, Together With Appendices of Related Elements and Photos of Significant Characters. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press, 1995, c1998.

- “Yellowstone National Park Visitor Statistics Page,” Yellowstone Up Close and Personal, accessed April 28, 2014 at http://www.yellowstone.co/stats.htm.

- Yochim, Michael J. Protecting Yellowstone: Science and the Politics of National Park Management. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2013.

For Further Browsing and Research:

- Yellowstone National Park: http://www.nps.gov/yell/index.htm.

- Yellowstone’s History & Culture: http://www.nps.gov/yell/historyculture/index.htm.

- Yellowstone webcams: http://www.nps.gov/yell/photosmultimedia/webcams.htm.

- Philetus Norris, second park superintendent: http://www.greateryellowstonescience.org/node/3310.

- Diary of a 1908 wagon trip from Boulder, Wyo., south of Pinedale, to Yellowstone Park: https://diaryfile.com/yellowstone-diary/. Special thanks to Matt McKnight, editor, DiaryFile.com.

- Greater Yellowstone Science Learning Center: http://www.greateryellowstonescience.org/.

- National Park Service Organic Act: http://www.nps.gov/grba/parkmgmt/organic-act-of-1916.htm.

- Expedition: Yellowstone! http://repository.uwyo.edu/starrs_curriculum/.

- Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) Curriculum http://repository.uwyo.edu/corps_curriculum/.

- Yellowstone Heritage and Research Center http://www.nps.gov/yell/historyculture/collections.htm.

- Grace Raymond Hebard Collection, Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections, University of Wyoming Libraries http://libguides.uwyo.edu/content.php?pid=285920&sid=2353001.

Illustrations

- The image of Thomas Moran’s “Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone” is from the Smithsonian American Art Museum via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- Hayden’s 1871 map of Yellowstone is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Philetus W. Norris is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Horace Albright eating supper with bears in Yellowstone in 1922 is by Yellowstone Park photographer George A. Grant, from Wikipedia.

- The photo of the 1988 fires approaching the Old Faithful complex is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The early William Henry Jackson photos of park features and the Hayden Expedition are all from the U.S. Geological Service photo library, easy to browse and search using the keyword search windows with names of photographers, dates, features, locations, etc. Used with thanks.

- The 1974 color photo of Castle Geyser in winter is from the Yellowstone photo collection, via Wyoming Places. Used with thanks.