- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Beaver Dick Leigh, Mountain Man of The Tetons

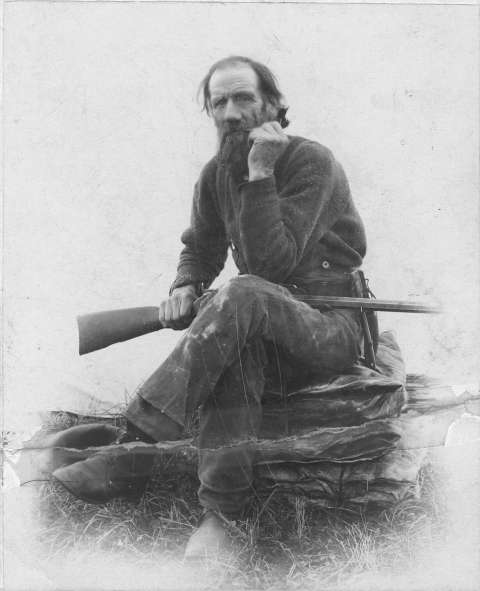

Beaver Dick Leigh, Mountain Man of the Tetons

The pack train moved slowly through the remaining snowdrifts of late spring in the Tetons, heading for the mountain valley ahead. The buckskin horses were led by a tall-for-his-time trapper with thick red hair and beard whom the Shoshone sometimes called Ingapumba (redhead), but more often he was known to his neighbors as “Beaver Dick” or “Uncle Dick.”

Following behind were his Shoshone wife, Jenny, and his children riding burros. They were leading pack horses loaded with supplies for a long season of camping, hunting and trapping in the high valley that even then was known as Jackson’s Hole.

In his 68 years, Beaver Dick Leigh fought in the Mexican War, guided government expeditions through the Yellowstone region and led hunting parties from the East—and enjoyed life among the Shoshone and Bannock tribes. With his red hair, blue eyes and freckles he certainly stood out from most of those around him, but despite his rough life he was an inveterate reader of books, magazines and newspapers. He kept a diary during his time in the mountains. He spelled his words as he spoke them, often dropping the “h” in keeping with his English-accent pronunciation.

Richard Leigh was born in Manchester, Lancashire, England, in 1831. When he was 7 years old he emigrated with his sister to America.

Dick and his sister, Martha, stayed in Philadelphia for a time, then moved on to Mount Hope, Pa. From there he later left his sister and joined the Hudson Bay Company, which sent him to the Northwest where his education as a trapper began. He never looked back, nor saw his sister again. He appears to have stayed in touch, however, as he later referred to his brother-in-law, Henry Wall.

Beaver Dick made his way from Canada back to the States to join the U.S. Army toward the end of the Mexican-American War (1846-48), in which he served under Lt. Col. Henry Wilson. He was possibly part of the siege of Vera Cruz and was stationed there through the end of the war.

Following his discharge, he travelled from the Rio Grande to the Salt Lake Valley where he resumed his prior trade as an independent trapper. Moving north into what would become Idaho Territory, he continued the trapper’s life, finally choosing the Snake River Valley as a favorable place for a homesite. This initially meant long pack trips south for a number of years to sell his furs in Utah Territory.

On one of these trips, in 1862, to Corrine, near the northeast shore of the Great Salt Lake, he camped near a Bannock couple—a man known as Bannock John to the whites, and his wife, Tadpole, a sister of the local Shoshone chief, Taghee. Tadpole was in the midst of a difficult labor and, with no other help available, Dick rendered assistance to the father in delivering the baby.

The new arrival was named Susan Tadpole by the couple. Her parents promised her to Dick to be his wife when she reached maturity. As he was 31 at the time, it no doubt was a kind gesture of gratitude that had little expectation of coming to fruition.

Before he returned to his base camp at the confluence of the Snake and Teton rivers on the west side of the Tetons, Dick Leigh married a 16-year-old Eastern Shoshone girl from Chief Washakie’s band in 1863. The ceremony was performed by a minister, but with no existing records, the bride’s Shoshone name is not known. Dick gave her the English name of Jenny.

Dick was obviously proud of Jenny’s work ethic and her contributions to their life together, for he often told his friends and wrote in his diary about her many good traits. The next few years were apparently happy for the couple. Five children arrived in the following years. Dick, Jr., was born in 1864, Anne Jane in 1866, John in 1868, William in 1870 and Elizabeth in 1873.

Dick’s homestead on the west side of the Tetons continued to expand with additions of milk cows and more of the buckskin horses he was so fond of. His diary continued to reflect his pride in his oldest son’s abilities and accomplishments. When it was time to go on the annual hunting trips over the mountains, Dick took the entire family along.

Image

The geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden, who had been in the valley with an army expedition led by Capt. William Raynolds in 1860, returned in 1871 at the head of a civilian, government-funded expedition to explore the Yellowstone region. Artist Thomas Moran and the photographer William Henry Jackson were also along. Hayden’s extensive promotion, along with Moran’s paintings and Jackson’s photographs, positively influenced the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872.

Hayden returned to the region with another survey party the following year to explore the area’s resources more extensively. On this trip, he employed Leigh as a guide. Hayden and his men were so impressed with the abilities and hospitality of Dick and Jenny that they named the lakes at the base of the Tetons for them: Leigh Lake, Jenny Lake and Beaver Dick, now known as String Lake.

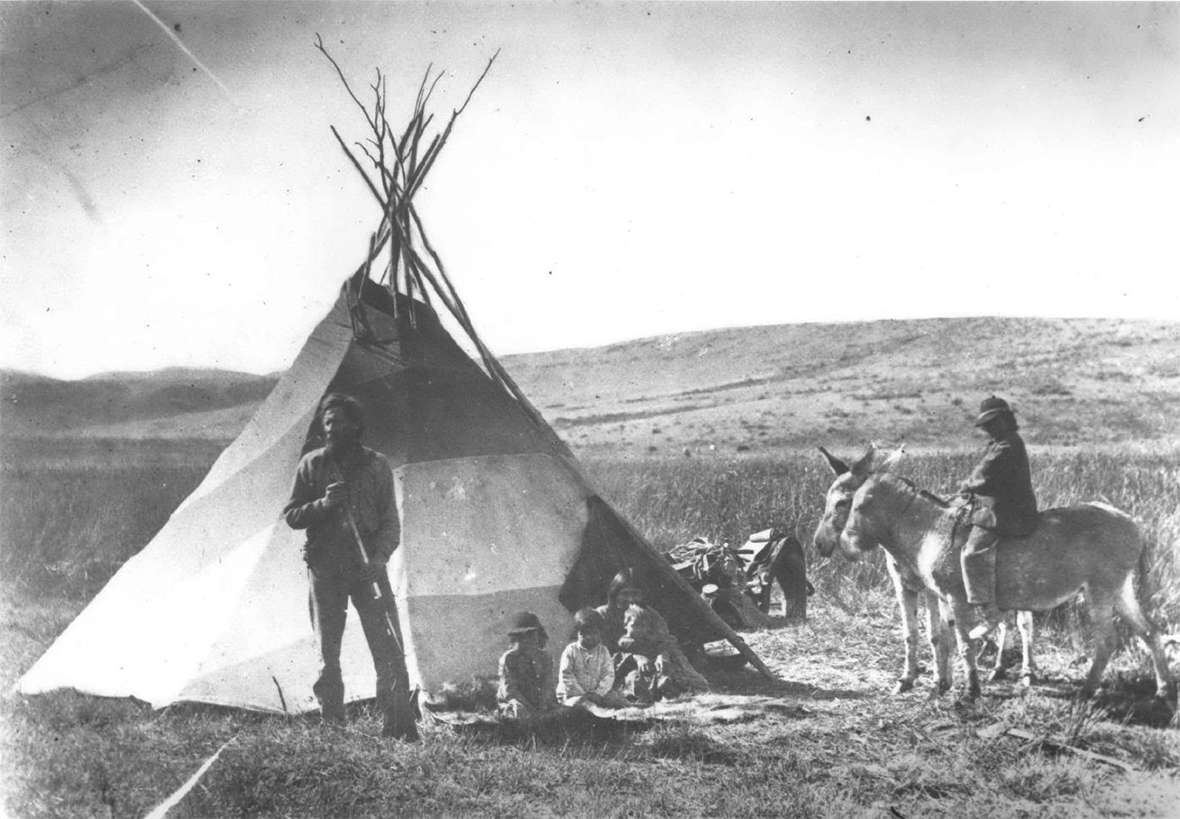

Beaver Dick joined the expedition at Eagle Rock, present Idaho Falls, and traveled north to Eagle Nest Ford, at what’s now St. Anthony, Idaho, in order to cross the Snake River safely. Leigh’s family accompanied the survey group, pitching their lodge near the main camp. Jackson photographed the family in front of their tipi. This is the only known photograph of Jenny.

Camping in the valley below the Tetons created a strong desire among some of the men to climb the tallest peak, despite Beaver Dick’s warnings. He told them the mountain had never been summited due in part to jumbled rock and timber around the base.

Nonetheless, a party of 14 was assembled, and the trek toward the top of Grand Teton began. Of those who started, five reached what is now known as the saddle. Nathaniel Langford and the climbing group’s leader, James Stephenson, continued to the peak, becoming the first known climbers to make the ascent. During their climb, Beaver Dick and another guide scouted a route through the Tetons and hunted meat for the camp.

The group continued to travel north about 20 miles and split up when they reached Conant Creek. Jenny, who was pregnant, and the Leighs’ four children returned to their homestead on the Teton River, while Beaver Dick continued on with the expedition party. After the family reunited at their home, they celebrated the birth of another daughter, Elizabeth, their fifth child.

Leigh’s diaries give an in-depth picture of the challenges they faced on the frontier. Whether he was setting his trap lines, hunting with his son Dick, Jr., leading hunting parties or assisting any of the increasing number of new settlers arriving in the Snake River valley, Beaver Dick Leigh was a busy and well-respected member of the community.

He also built a ferry at the Eagle Nest Ford on the Henry’s Fork of the Snake, which was free for anyone to use. He even acted as liaison between the tribes and authorities at the new Fort Hall Reservation, advising them about Indian movements on and off the reservation. .

The next few years passed peacefully until the winter of 1876, when an Indian woman seeking food visited the Leighs. They did not know that she had been infected with smallpox. All of the Leigh family as well as another hunter caught the disease. Between Christmas Eve and Dec. 28, 1876, all of Beaver Dick’s family died; he and the hunter barely survived.

For two years, Dick suffered and struggled to maintain as normal a life as possible on the homestead. In the summer of 1878, some Bannocks left the reservation in a protest over the government’s failure to send promised food and supplies, in a series of events that came to be known as the Bannock War. Beaver Dick and his friends Bannock John and Tadpole laid low, staying out of sight to “keep their hair,” as he put it—that is, to remain unscalped.

In the spring of 1879, Dick Leigh, at age 48, married 16-year-old Susan Tadpole, who had been promised to him at her birth. The couple had three children: Emma, born in 1881; William, born in 1886; and Rose, born in 1891.

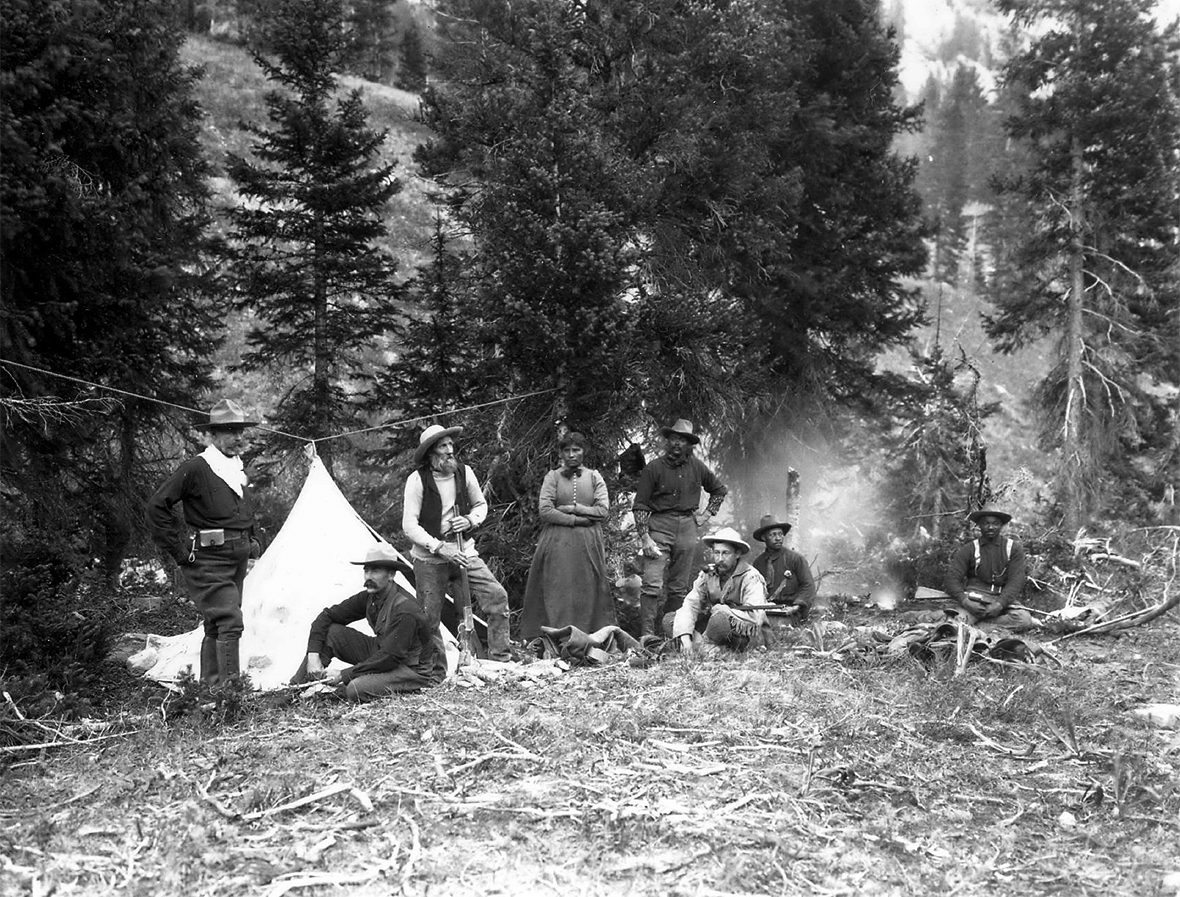

As before, when it was time to head to the mountains to hunt and fish, Dick took his new family with him. While camped near Two Ocean Creek on the Continental Divide in the fall of 1891, they were visited by Theodore Roosevelt and his hunting party. Beaver Dick and Teddy conversed for a spell, sharing stories and hunting tales.

Dick continued to guide hunting parties as long as his health permitted. Eventually he had to turn over this business to his son William. He also kept in touch with the many friends he had made over the years, writing letters to a lengthy list of correspondents.

Beaver Dick Leigh died March 29, 1899, age 68, in the company of family and friends. He is buried beside his family on a high terrace overlooking his ranch near Rexburg, Idaho.

His memory and legacy are well preserved in his letters and diaries, as well as the namesake features in the Jackson Hole valley he loved.

(Editor’s note: Special thanks to “Chronicle,” the newsletter of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum, in which an earlier version of this article appeared in the Winter 2014-15 issue.)

Resources

- Calkins, Frank. Jackson Hole. New York: Knopf, 1973.

- Daugherty, John, Crockett, S., Goetzmann, W. H., Jackson, R. G. and United States. A Place Called Jackson Hole: The Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park, 1st ed. Grand Teton National Park: National Park Service, 1999.

- Nelson, Fern K. Mountain Men of Jackson's Hole: Colter, Hoback, Jackson, Leigh. Jackson, Wyo.: Jackson Hole Museum, 1989.

- Thompson, Edith Schultz, & Thompson, William Leigh. Beaver Dick, the Honor and the Heartbreak: An Historical Biography of Richard Leigh. Laramie, Wyo.: Jelm Mountain Press, 1982. The book quotes extensively from Beaver Dick Leigh’s diaries and letters. William Leigh Thompson is Beaver Dick’s great-grandson.

For further reading and research

- Beaver Dick Leigh’s diaries from 1875, 1876 and 1878 are in the collections of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. At http://digitalcollections.uwyo.edu/luna/servlet, enter “Leigh, Richard” in the search window for access to the diaries in PDF format.

Illustrations

- All photos are courtesy of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. Used with permission and thanks.