- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Aven Nelson, Botanist and President of The Univ...

Aven Nelson, Botanist and President of the University of Wyoming

When 28-year-old Aven Nelson arrived in Laramie, Wyo., on July 28, 1887, the University of Wyoming consisted of just one building, still under construction, on an arid plain dotted with sagebrush and a few cows—a landscape that was far different from the Iowa of his birth and the part of Missouri where Nelson had lived most recently.

But the look of the new campus may not have been as surprising as the job news he received soon after he and his wife, Celia Alice, stepped off the train with their baby Neva.

He planned to be the English professor. However, the UW trustees had goofed, inadvertently hiring two English instructors. The other man had a master’s from Dartmouth. Nelson had a bachelor’s in arts and didactics from the Missouri State Normal School. After university President John Hoyt discussed the matter with him, and because he had taught biology at Drury College in Springfield, Mo., Nelson, one of the university’s six first faculty members, was appointed biology professor and librarian.

For a $1,500 a year, Nelson’s duties also included serving as calisthenics instructor and teaching physical geography, economic botany, zoology and animal physiology. Not until 1891 and the creation of programs in agriculture and horticulture did Nelson discover the profession he loved the most, a position that eventually brought him international and long-lasting respect. He became the professor of botany and horticulture, and in time earned the nickname “the botanist.”

By 1891, the university boasted a new experiment station, where faculty and students could try out new agricultural methods on crops and livestock. That year, Nelson published the first botanical report, a short list of the plants he’d found growing locally and on unirrigated parts of the university’s experiment farm. He included fifteen plants and added 8 plants and shrubs that grew in the hills near Laramie.

In 1892, Nelson was granted a leave of absence and earned his master’s degree from Harvard, where he did course work on the morphology and physiology of plants and animals. By this time, he and his wife had two daughters—Neva, born in 1886, and Helen, born in 1891.

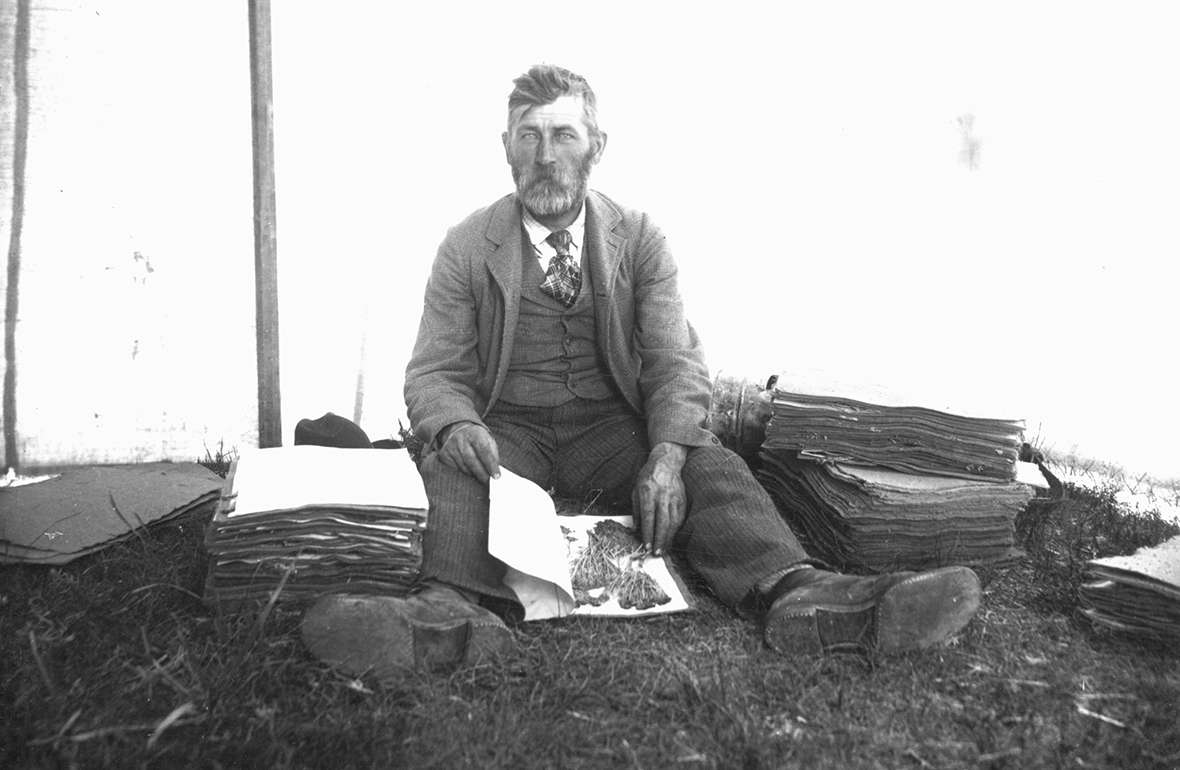

Beginning the herbarium

Meanwhile, university horticulturalist Burt Buffum had prepared plant specimens from throughout Wyoming for the state’s exhibit at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Nelson, when he returned to Laramie, was assigned the task of identifying the plants. This became the beginning of the herbarium—a sideline to Nelson’s full-time teaching load.

Having no formal botanical training, he relied upon the respected manuals of the day, including John Coulter’s Manual of the Botany of the Rocky Mountain Region. Nelson and the university’s Edwin Slosson, the chemistry professor, displayed in Chicago the collection of grasses that Buffum had collected. They earned a medal for the University of Wyoming.

Because Nelson was eager to learn more, he set aside extra sets of specimens so he could exchange or sell the sets and receive more plants in return. He began collecting and preserving plants himself in and around Laramie in 1893. He often worked nights, after teaching during the day. Through these plant exchanges, he learned from other more experienced botanists—ones from Harvard, Berkeley and the National Herbarium in Washington, D.C., for example—how plants were named and proper preservation methods. But Nelson realized he would need more formal training as well.

Grace Raymond Hebard, who the UW board of trustees hired as its secretary in 1891, had received her Ph.D. from Illinois Wesleyan University, where residency—unusual for such an advanced degree—had not been a requirement. At a time when the great majority of the Wyoming faculty did not possess the degree, “her acquisition [of it] was as worrisome to them as it was dubious,” Roger Williams writes in his biography of Nelson.

Hebard was already a powerful force on the campus. In her position as secretary to the board, she also signed the reappointment letters for faculty members. Nelson’s salary, which was supposed to have been increased to $1,800 after he earned his master’s degree, actually decreased to $1,600. He began looking elsewhere for positions but found he’d need a Ph.D. to pursue university botany jobs elsewhere.

Botanizing in the Red Desert and Yellowstone

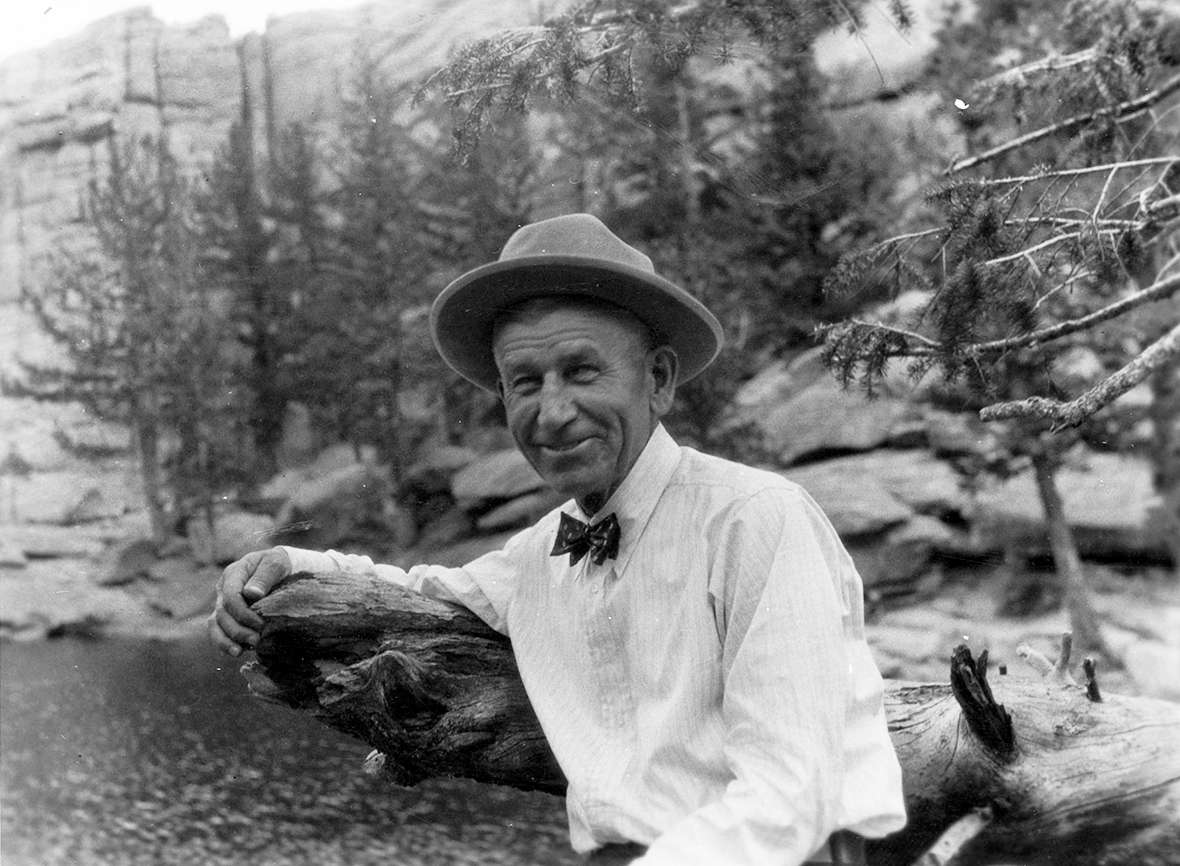

Nelson, therefore, stayed on in Wyoming, learning botany as he worked. By 1895, he had begun to earn respect from botanists throughout the nation for his collections. His “First Report on the Flora of Wyoming,” published in May 1896 in the Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, listed 1,176 species found in Wyoming.

He began selling specimen sets to fund field work. In the summer of 1897, he worked on commission for the Division of Agrostology of the U.S. Department of Agriculture to collect grasses and forage plants in the Red Desert of south central Wyoming at a salary of $150 per month. He was the first botanist to study the Red Desert systematically.

In 1899, he traveled to Yellowstone National Park to collect specimens. He funded the trip by selling subscriptions for duplicate sets at a price of $8 per 100 species and $100 for a full set, no matter the number of species that were included. He did not make as much as he hoped, but this did not thwart the trip. “Whatever else the Yellowstone expedition did for Aven Nelson and Wyoming,” Williams writes, “it made him a Wyomingite for the remainder of his life.”

The party included Nelson, his wife and young daughters, graduate student Elias E. Nelson (no relation) of Douglas, Wyo., who worked as his assistant, and Leslie Goodding, a high school student in the university preparatory school who did camp chores. In mid-June 1899, they traveled by train courtesy of the Union Pacific Railroad from Laramie to Monida, Mont., on the Montana-Idaho border west of Yellowstone Park.

They explored the park by horse-drawn wagon, camping along the way in a 12-by-14 tent. They collected about 1,400 specimens during the trip, but there were mishaps. A grizzly bear frightened the horses away from the camp; they turned up later about five miles off. More seriously, Elias Nelson stepped into hot mud and suffered a severe burn on his ankle. He returned home early.

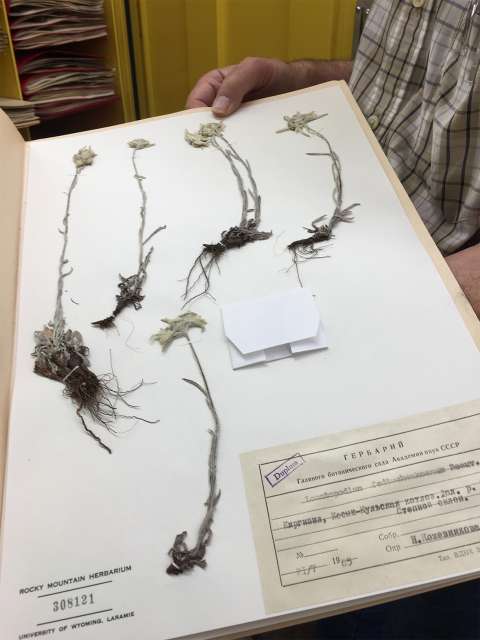

That fall, Nelson hired Goodding as an assistant for $500 for the academic year, and the university’s board of trustees approved the instructor’s request that the herbarium be named the Rocky Mountain Herbarium. He was named curator as well. Elias Nelson of the burned ankle went on to earn the first graduate degree awarded by the university, but he did not become a botanist.

Earning well-deserved acclaim

In 1904, Aven Nelson earned his Ph.D. from the University of Denver, awarded in part because of his previously published botany articles, and also, Williams notes, because that university’s officials “were eager to honor him as the preeminent botanist of the Rocky Mountain region, and thus, bring honor to themselves.”

Burrell “Ernie” Nelson, present-day curator of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium—no relation to Aven Nelson—notes that Aven Nelson made the herbarium “the center of botany for the region.” Aven Nelson was the first botanist to actually live in the region and ended up rewriting the Coulter Manual of Rocky Mountain Botany with which he’d begun his own education in botany years before. The book remained “a key reference for the region for years,” Ernie Nelson says.

Enduring academic disputes

That task, completed in 1908, earned Aven Nelson wide respect as a taxonomist. But there had been serious difficulties at the University of Wyoming beginning the previous year that had again caused Nelson to look elsewhere for employment.

The controversy began with an exchange of a 5,000-acre tract of university-owned land in Big Horn County for a tract of similar size in Park County. The swap was approved by the state land board, but without first consulting the university trustees. Since the new tract was likely to provide more revenue than the old one, the trustees had no objection, but UW President Frederick Tisdel felt strongly that the exchange was improper and set “a most unfortunate precedent,” Williams writes.

Since the trustees were largely Republican and the Wyoming government was led by a Republican administration, some trustees—including Hebard and Laramie businessman Otto Gramm—interpreted Tisdel’s concern as a political criticism. He resigned, offering an effective date in June, but the board dismissed him on March 28, 1908.

Hebard’s authority came into question that year as well, but she emerged unscathed. She became an associate professor in the political economy department in 1906-1907 without consulting the department head. She did not teach a class, and her superior questioned the credibility of her Ph.D. In addition, with her position as secretary to the board of trustees, her salary as professor and librarian topped his by $200. When he requested her removal, he lost his job, and Hebard became head of the department. Deborah Hardy, who in the 1980s wrote a history of the university’s first 100 years, notes that while Hebard’s intentions were probably noble, “her position as faculty overseer and financial dragon had caused her to become heartily disliked.”

By this time, Nelson had worked for the university for 20 years and invested much of his time and talents in the Rocky Mountain Herbarium. He had earned wide respect in his field, but he did not find anything that suited him better. The university, Williams notes, had “come close to losing its best and on the eve of his greatest scholarly achievement. It also had Miss Hebard, who brought trouble but no distinction, for life.”

Serving as president

In 1917, the University of Wyoming trustees appointed Aven Nelson to serve as temporary president following Clyde Duniway’s move to Colorado College. Nelson had served as vice president for the three years previous. He accepted the new position in part because the trustees promised to continue searching for someone to fill the post permanently—an uncertain task, given that the nation had just entered World War I. Nelson continued to teach freshman botany. His salary was $5,000 per year, the same that Duniway had earned.

In 1917, the university hired a professional campus gardener. Before that, Nelson had taken care of the campus by planting trees and shrubs and grass to replace sagebrush. He had enlisted students to help him with pruning, trimming and mowing and general upkeep in an annual event called “Nelson Day.”

Nelson continued as president until 1922. During his term, wartime inflation and the receipt of oil royalties from state lands helped the university prosper. Nelson worked to increase faculty salaries and create a pension system and workmen’s compensation packages. But he always wanted to return to botany. According to Hardy, one student called him “part poet” and referred to him as a “great teacher,” but an “indifferent administrator.”

Hardy lists the three presidents who followed Tisdel—Merica, Duniway and Nelson—as having “worked well with faculty and earned the respect of their colleagues on campus.” But in 1922, after making some controversial decisions, including reconsidering the position of the popular football coach, Nelson submitted his resignation and the board granted him a leave of absence.

He was 63; he and his wife took the opportunity to travel the West and do field work. In the summer of 1923, Aven also taught students attending the University of Wyoming summer science camp in the Medicine Bow National Forest about 40 miles west of Laramie in the Snowy Range. The camp was the brainchild of geologist Samuel Knight and attracted students from across the nation.

In 1925, he began to revise the Coulter-Nelson manual, a project he called the “Dual Purpose Manual,” referring to his efforts to make it serve both professional botanists and amateurs. In 1926, the University of Colorado awarded him an honorary doctorate. In 1927, he became a founder of the Colorado-Wyoming Academy of Science.

Remaining vibrant in later years

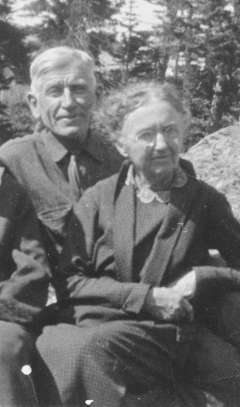

Beginning in the 1920s, Nelson’s wife, Celia Alice, known also as Allie, suffered from an intestinal ailment for several years. She died on Aug. 9, 1929.

The next year, Nelson took a four-month European tour, visiting Norway, the country of his ancestral heritage. When he returned to the U.S., he visited various campuses, including Colorado Agricultural College in Fort Collins, Colo. While there, according to Williams, he spoke with a graduate student, Ruth Ashton, who had worked summers for the National Park Service and planned to write her thesis on the plants of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Nelson had met her at a meeting of the Colorado-Wyoming Academy of Science and invited her to conduct research for her thesis at the Rocky Mountain Herbarium. When a $500 assistantship became available at the RMH, Nelson awarded the position to Ashton. “Her interests,” according to biographer Williams, “… squared well with his own ambitions for a dual-purpose manual.”

The two fell in love, despite the vast difference in their ages: Nelson was 71; Ashton, 34—younger than both of his daughters. Nelson conducted field work for the state of New Mexico in 1931. Aven and Ruth married in Santa Fe on Ruth’s birthday, Nov. 29, 1931.

Although Nelson’s daughter Neva knew her father hoped to remarry, he had not shared definite plans with her. Nelson wrote a letter to his daughters the next day, but the news appeared in newspapers before they heard from their father. While this caused a short-term rift, the family made peace with each other eventually.

“This astonishing man,” writes Harvey, “found happiness in a second marriage to a sympathetic and loving woman, also a botanist.”

Nelson remained active during his later years. Although his publisher rejected the dual purpose manual, he lectured throughout the world; was elected as president of the Botanical Society of America in late 1934, and in December 1935 became the first president of the American Society of Plant Taxonomists. In 1937, the University of Wyoming awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws. The same honor was bestowed posthumously that year on Grace Raymond Hebard.

Aven Nelson continued teaching at the UW summer science camp until 1938. During the summer of 1939, Aven and Ruth Nelson collected plants in Alaska in Mount McKinley National Park. He continued to do field work until 1945. In 1945, he fell from a chair while attempting to retrieve a book from a high shelf. He hit his head on the concrete floor and never completely recovered. By 1947, he was experiencing cognitive challenges, and it became increasingly difficult for Ruth to care for him in Laramie. He died March 31, 1952—just a few days after turning 93—at Brady Sanitarium in Colorado Springs. He was buried in Greenhill Cemetery in Laramie. Ruth Ashton Nelson died on July 4, 1987.

A continuing family legacy

Aven Nelson’s students often felt close to him, according to Williams. “Botany students were never just students to Professor Nelson,” Williams explains. “Let any student evince an interest in his field, and he or she gained instant entry to a charmed circle.”

His legacy proved to be a lasting one. Charlotte Reeder, who Aven Nelson considered like a granddaughter, was the daughter of Leslie Goodding, the young man who went to Yellowstone with the Nelsons in 1899. Goodding eventually chose a career in botany and had looked upon Nelson as a father figure. Reeder, likewise a botanist, became current RMH curator Ernie Nelson’s mentor in graduate school. The affiliation with Reeder allowed Ernie Nelson to become, in effect, a latter-day student of Aven Nelson.

“So much of what I learned was indirectly from him,” Ernie Nelson says. Aven Nelson’s work in botany and at the University of Wyoming further influences the current curator because, he says, of “the work he had done to increase the knowledge of what plants occur in Wyoming, a great foundation, which I could help build on.”

Today, visitors to the University of Wyoming campus--especially those who pass through Prexy’s Pasture--stroll past large spruce trees that Aven Nelson planted. He may also have planted some of the older cottonwoods, according to Ernie Nelson. Located at the far west side of Prexy’s Pasture, the herbarium, perhaps Aven Nelson’s greatest contribution to botany, takes up the entire third floor of the Aven Nelson Building. The collections total approximately 1.3 million specimens. The building was constructed in 1922 and first served as a library. After a new library was built, the herbarium and the botany department were located for a time in the UW Engineering Building and were moved to their current location in 1960. The building also houses the U.S. Forest Service National Herbarium and the W.G. Solheim Mycological Herbarium. Efforts are underway to digitize the collection, with 850,000 specimens currently available to be searched online.

The plant Anelsonia eurycarpa, a daggerpod from the mustard family, was named in honor of Aven Nelson.

Resources

- “Anelsonia.” Wikipedia. Accessed Sept. 20, 2018, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anelsonia.

- Ewig, Rick and Tamsen Hert. University of Wyoming. The Campus History Series. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2012, 28-29.

- Fertig, Walter. “Aven Nelson’s 1899 Yellowstone Expedition” Vol. 18, no. 4, Dec. 1999, Castilleja (The Newsletter of the Wyoming Native Plant Society).

- Hardy, Deborah. Wyoming University: The First 100 Years, 1886-1986. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming, 1986, 45, 73-75, 79, 88. Hardy’s book also provides additional details about the operations of the university and Aven Nelson’s role at UW.

- Knobloch, Frieda E. Botanical Companions: A Memoir of Plants and Place. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2005, 29, 39, 83. In this book, Knobloch, associate professor of American Studies at the University of Wyoming, relied upon previous research conducted by Aven Nelson biographer Roger Williams but refers in greater detail to Ruth Ashton Nelson's life and work, also attempting to better understand her personal relationship with her husband through the work they performed together. As part of her research, Knobloch, who is not a botanist, traveled to Wyoming's Red Desert and to Alaska and collected specimens in the same areas as the Nelsons had many decades before.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. 2d ed., rev. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, 343, 364, 399, 430.

- Nelson, Burrell “Ernie.” Email interview with author, Aug. 26, 2018.

- Nelson, Aven. Title unreadable [regarding state flowers], Laramie Republican, April 2, 1917, p. 6. Accessed Sept. 6, 2018, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

- Williams, Roger L. Aven Nelson of Wyoming. Boulder, Colo.: Colorado Associated University Press, 1984. Considered the definitive biography of Aven Nelson and highly recommended by botanists. This book contains much detailed information about Aven Nelson’s professional and personal life, including examples of taxonomy, Nelson’s “Proposed New Genera, Species, and Varieties,” and a detailed listing of his publications. I relied heavily upon this source in writing this article. See especially 26, 28, 40, 59, 61, 67, 70-78, 124-126, 151-153, 200, 238-239, 256, 263, 271, 276-296, 288-289.

- “Aven Nelson.” Find a Grave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/52105750/aven-nelson

- “Aven Nelson, UW Professor and President.” UW Profiles, University of Wyoming. Accessed July 13, 2018, at http://www.uwyo.edu/profiles/distinguished-leaders/aven-nelson.html

- “Aven Nelson.” Office of the President. University of Wyoming. Accessed July 13, 2018, at http://www.uwyo.edu/president/past-presidents/aven-nelson.html

- “Aven Nelson.” Wikipedia. Accessed Sept. 19, 2018, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aven_Nelson

- “Rocky Mountain Herbarium.” University of Wyoming. Accessed Sept. 18, 2018, at https://www.uwyo.edu/botany/rocky-mountain-herbarium/.

- Ruth Ashton Nelson, 1896-1987. WorldCat. Accessed Sept. 19, 2018, at http://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n89644161/.

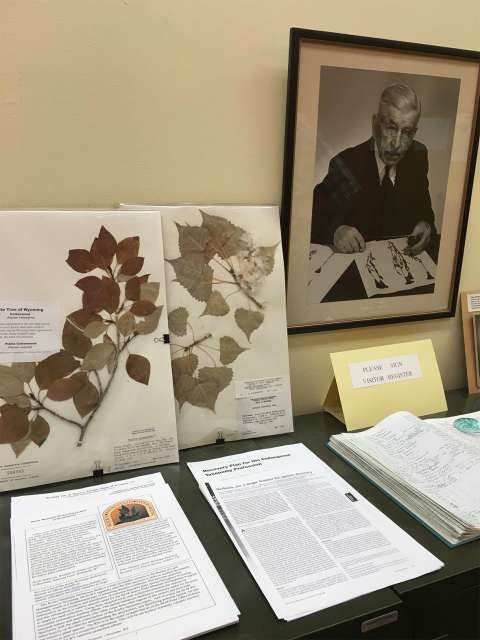

Illustrations

- The black and white photos are all from the digital collections at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks. Special thanks to botanist George Jones of the university's Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for identifying Nelson's vasculum.

- The color photos are by the author. Used with permission and thanks.