- Home

- Encyclopedia

- John Muir In Yellowstone

John Muir in Yellowstone

Pity the poor visitor to Old Faithful who finds the geyser’s rumbling sounds, acrid smell and burbling, incipient explosion mirrored inside his body. In August 1885, Yellowstone National Park’s most famed attraction erupted and, the visitor wrote, his stomach “began spouting vast quantities of hot acid water in close accord.”

That tourist, on his first visit to a national park, was famed naturalist John Muir, often known as the Father of the National Park System. He spent a week camping in the then-primitive preserve, enduring hardships and making notes.

Yellowstone had been set aside just 13 years earlier as a curiosity full of natural oddities. But Muir, a man who advocated for a holistic, spiritual view of nature, helped Americans see their first national park as more than collection of weird phenomena and instead envision a glorious natural system.

Muir’s published writings speak rhapsodically about Yellowstone and ignore his personal discomforts. His letters and journals, however, give an intimate picture of the Yellowstone he experienced. Muir’s insights shaped the way Americans saw Yellowstone, and thus the way the park’s wonders are presented to the public, even today.

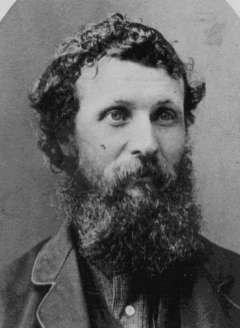

John Muir, naturalist

Born in Scotland in 1838, John Muir moved to rural Wisconsin with his family at age 11. His evangelical father, a harsh disciplinarian, worked him hard on the family farm. In his 20s, Muir rebelled, moving first to Madison, then to Canada—to avoid being drafted during the Civil War—and then to Indianapolis. He forged a promising career as an inventor of machines on factory floors. But after an industrial accident nearly blinded him, he gave up that career to wander and observe nature.

Muir discovered the Yosemite Valley in 1868 and lived there full time for three years. He spent the 1870s exploring California, especially the Sierra Nevada. He published articles on glaciation and natural history. In 1880, at age 42, he married Louie Strentzel and moved to her family’s orchard and ranch in Martinez, Calif. He cut down on his traveling and writing to help manage the orchard and start a family.

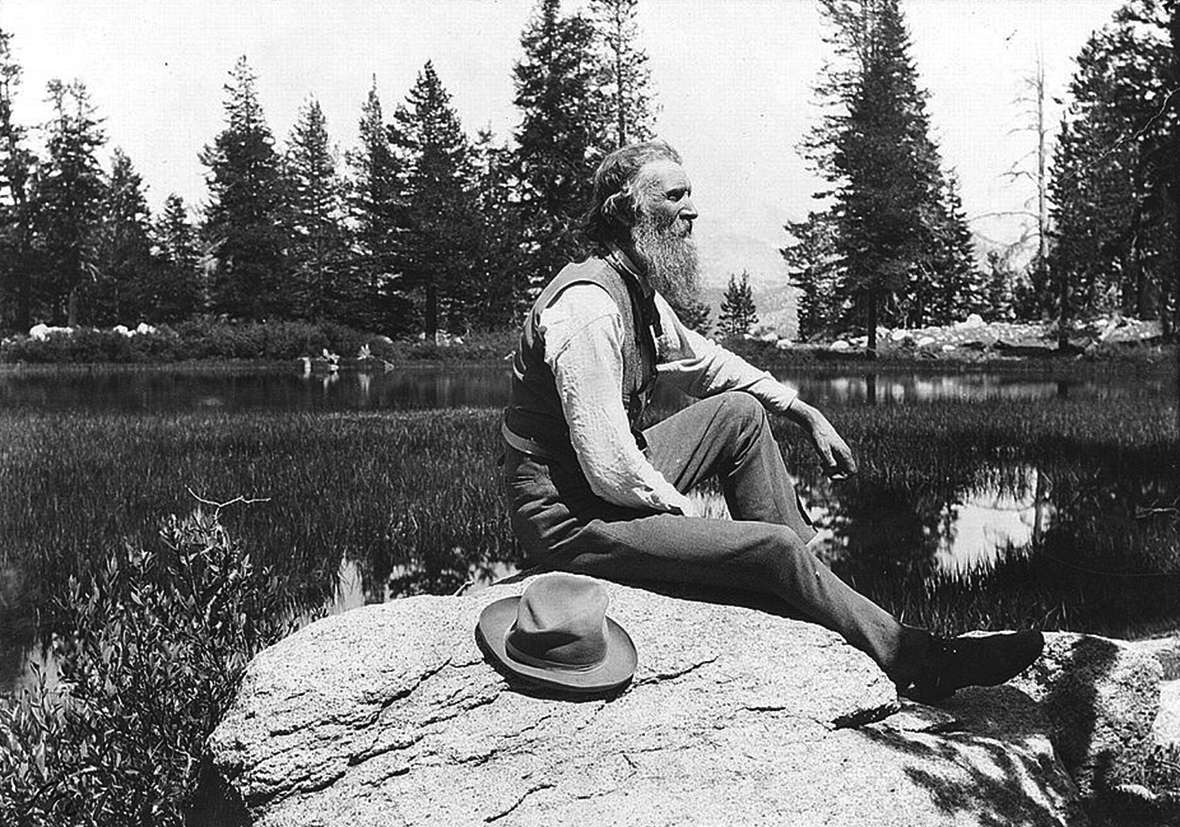

A slender man with a full, long beard and keen but kindly eyes, Muir gave little thought to his appearance and often dressed in tatters. Bashful in his youth, he gradually became known as a grand storyteller, delivering his tales in a rich Scottish brogue. His early articles won him some attention among cultured Californians, but not until the 1890s did he achieve nationwide fame by publishing books and founding the Sierra Club. In 1885, he still was simply a man who loved wild places and occasionally wrote about them.

That year marked one of the most responsibility-laden periods in Muir’s life. Louie was pregnant with their second daughter. He had taken over daily supervision of the estate from his father-in-law. Yet he now felt compelled to travel back to Wisconsin to visit money-strapped siblings and his melancholy mother. He had not been back in nearly 20 years, and worried that his parents were both on their deathbeds. (His father, living in Kansas City, would in fact die during John’s visit.) He dreaded the three-month trip.

A stop in Yellowstone National Park

Muir’s route took him first to northern California’s Mount Shasta, which had always enticed him with its green meadows, vast woods, deep streams and icy mountain cone. “ Never while I live will this mountain love die,” he wrote Louie. “Though on the way to see my aged mother and father and sisters and brothers and old friends and neighbors, I still feel a strong draw to the wilderness impelling me to leave all and linger here. But I will not—putting away the temptation as a drunkard would whiskey.”

He made his way north to Portland, Ore., then east on the Northern Pacific railroad. The line through the Montana and Dakota territories had been completed less than two years earlier. A highlight was its branch from Livingston, Mont., 51 miles south to Cinnabar, at the northern edge of Yellowstone Park.

Muir was tired. Descending from the rail car, he doubted his powers of endurance. He hadn’t felt this weak since a bout with malaria in Florida in 1868. Even at the beginning of this trip he’d felt tired. Digestion and stomach pain complicated his journey. In Portland, a doctor had given him prescriptions for pills and a stomach powder that reminded him, he wrote, of “powdered lava or Red Bluff dust.”

Worse, Muir knew that a mere week in Yellowstone would not do it justice. “ Afraid I will not learn much,” he wrote Louie, “still I may get some good facts besides the mere pleasurable mass of wonderment from the spouting steam and muds and suds.”

“Gray and ashy and forbidding”

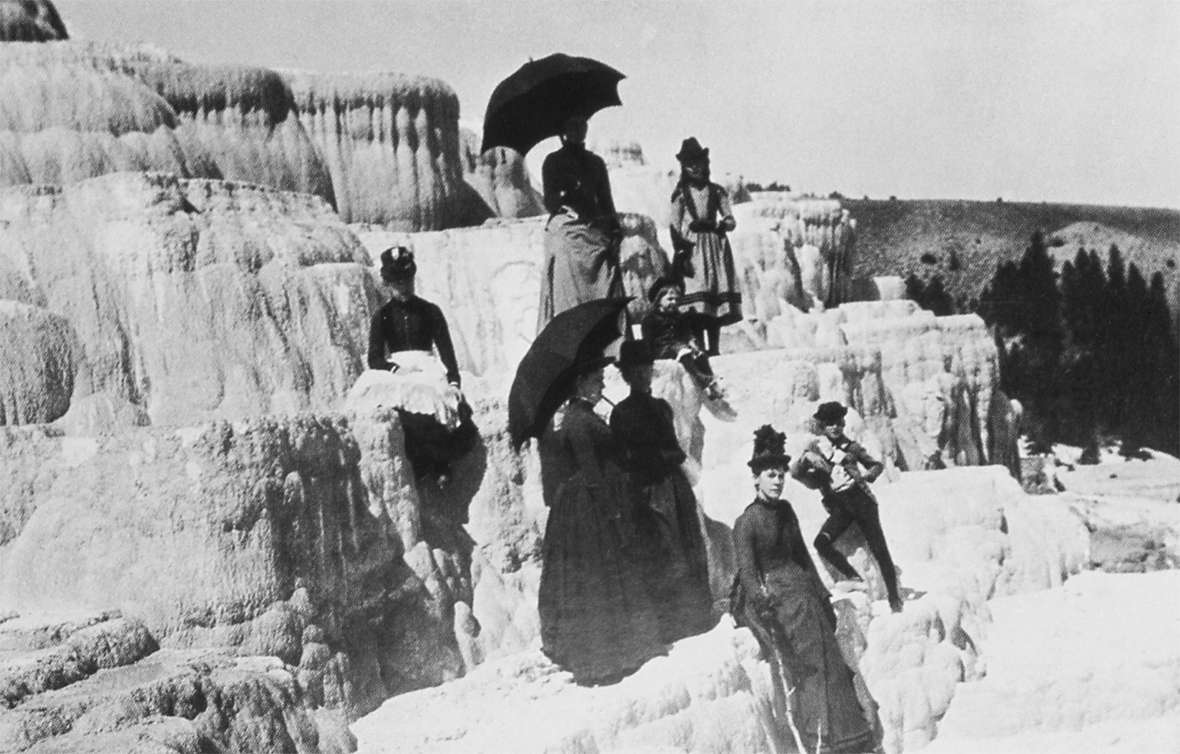

Yellowstone made a poor first impression. Muir found the sagebrush-covered hills between Cinnabar and Mammoth Hot Springs “ gray and ashy and forbidding … here and there rough gray junipers and two-leaved pines, far away removed from the freshness and leafy beauty of Yosemite.” At first glance, Mammoth’s famed terraces reminded him of “the refuse heaps about chemical and dye works.”

If the natural setting was uninspiring, the human culture was repulsive. At the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel, he described one meal as a “ hot soda biscuit and gray-looking lava-like puddings with blood-curdling sauce and slime, more wonderful in color, some of them, than the variegated geyser muds." In the morning, touring the odd, bright-colored terraces, he found the sun’s glare overwhelming. He went back to the hotel to rest.

After a bad, expensive lunch, he tried again to tour the terraces, but managed only after vomiting up the meal. Supper too was “ abominable,” but he learned some facts and made some friends. Alfred and Fay Sellers, honeymooners from Chicago, joined him in hiring horses and a cook and guide for a 150-mile tour.

That trip created additional hardships, with plenty of rain and hailstorms. He wrote Louie: “In galloping along a smooth piece of ground my horse[’]s front feet broke into a hole[,] he fell head over heels pitching me ahead half a mile or so, whirling me over in somersaults.” And the guide they’d hired proved no better at cooking than the chefs at the hotel.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, too, disappointed him with its lack of trees. He described its walls in his journal as “ half ashes half stone.” Near Hayden Valley, they encountered “much fallen and burnt timber.” At Old Faithful, Muir again vomited, this time in perfect sympathy with nature’s geyser. He told Louie, “it was all very violent very painful very wonderful.”

Painful and wonderful

The surprise of that word used in the context of his distress—wonderful?—demonstrates an essential core of Muir’s philosophical outlook: his insistence that our innermost selves are connected deeply to the natural world and, through Nature, to God. Like Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Muir tended to replace “God” or “the Lord” with “Nature” or “Beauty” as if they meant the same thing.

This extreme theology helps explain why he would happily experience pain—from nausea to miserable weather to sleeping on hard ground—if the pain brought him close to rocks and trees and animals. If he and Old Faithful were retching at the same time, that was magnificent harmony. Places like Yellowstone and Yosemite, being remote and undeveloped, might produce a lot of this human discomfort, but also bring close the wonder of nature.

However, Muir seemed to understand that not everyone shared his high tolerance for pain. When publicly proselytizing for nature, he skipped over the complaints that he made in private letters. Likewise, he omitted his initial perceptions of Yellowstone as bizarre. He believed nature was a sort of “divine government,” and he intended to show it at work. In the Yellowstone essay he published later that autumn, he focused not on his experiences but on the scientific facts he had worked so hard to learn.

Wholeness

Muir’s writings depicted Yellowstone as an educational place. He seemed most captivated by the notion that in this region were the headwaters of the Missouri, Snake and Green Rivers, flowing to the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf of California, respectively. Being the fountain of such great and diverse rivers gave it a wholeness, a unity. As a place of origin for rivers, it was also one for the human spirit.

“To everybody over all the world water is beautiful forever,” he wrote, “whether falling upward into the sky in snowy geysers, or downward into deep resounding cañons, or gliding and resting in calm rivers and lakes.” He portrayed Yellowstone as a “capital camping-ground” with lakes, parks, meadows, woods, streams, and waterfalls.

Now, no longer described as chemical wastes, the Mammoth Hot Springs were “terraced hills of marble or silex, pearly white, tinged here and there with delicate pink …”

The geysers, he wrote, “display an exuberance of strange motion and energy admirably calculated to shake up, and surprise, and frighten the dullest observer out of soul-wasting apathy, and make him begin to grow and live again.”

Closer to God

Muir had experienced Yellowstone the same way most visitors did at the time, and, despite dramatic improvements in food and transportation, largely the way most people do now. He didn’t backpack to hidden valleys or discover previously unknown geological features, as he had at Yosemite. A tourist, he visited the main wonders and spent far less time with them than he knew he should have.

In many ways the trip’s bright spot—certainly its most lasting effect—wasn’t any of the natural features but the people he met: The Sellers became lifelong friends.

Yet in part by putting in the hard work to dig up facts, he was able to overcome the hardships and transform his initial impression. And because he could write so eloquently, he also transformed the way others saw the park.

His depiction went beyond Yellowstone’s wonderful strangeness. He concluded that it was not merely a collection of smoky vents, surprising gushers, and odd terraces with industrial odors. It was not merely a geology field trip. It was not merely a vast mountain lake flowing into a peaceful stream and then a stunning canyon.

It was a place, he wrote, where “harmony rules supreme. Linnaea [twinflower] hangs her twin bells over the rugged edges of the cliffs, forests and gardens are spread in lavish beauty round about, the nuts and berries ripen well, making good pastures for the birds and bees, and the bears also, and elk, and deer, and buffalo—God’s cattle—all find food and are at home in the strange wilderness and make part and parcel of the whole.”

With words like harmony and whole, Muir was conveying his vision of nature as holistic, a system, God’s system. Part of the joy he felt in nature was an appreciation of his place in that system, in God’s world. And he was an evangelist about that feeling: He wanted others to feel it, too.

At the time, most Christians held that nature was a collection of resources for people to exploit—man held dominion over beasts. Muir, by contrast, was biocentric. In his radical interpretation, God created nature for nature, not for people. Muir believed that by experiencing nature on its own terms, rather than as a collection of timber, grass, game, minerals and water, people would be closer to God.

Political implications

At the time, the notion of a national park may not have meant much to Muir. Indeed the phrase probably meant little to anyone in those early years when the nation had only one park and its management philosophy was not yet clear.

Muir came to Yellowstone, and chose to write about it, because it was a celebrity among landscapes, a “strange region of fire and water” that would spark readers’ curiosity. He would have been happier at Mount Shasta, even though it wasn’t a national park. Yet he applied his unique insights in Yellowstone, and that vision helped send Yellowstone on a journey: from a place of majestic curiosities to a place reflecting deep American values.

When it was established as the nation’s park, Yellowstone was the equivalent of a city park—like New York’s Central Park, which was developed at about the same time. A detractor might wonder why a park was needed in a remote, rural area and why it should be held by a federal government. Muir helped Yellowstone become more: a symbol of nature as vast, holistic system; an embodiment of God on earth; a physical representation of American ideals and a fountain of the soul.

A second visit

Muir returned to Yellowstone 11 years later. In 1896 he visited as part of the National Forest Commission, whose members toured dozens of Western parks and forests in order to make recommendations to President Grover Cleveland about public land policy. On this trip the increasingly famous Muir was surrounded by other notable personages, including Harvard botanist Charles Sargent and Yellowstone geologist Arnold Hague. Because Muir was likely engaged in so many conversations with them, he spent less time writing letters and journals about his experiences.

However, this visit led to a more famous 1898 essay on Yellowstone, which Muir published in the Atlantic and later included in his book Our National Parks. This text was primarily descriptive, with lots of travel advice: “If you are not very strong, try to climb Electric Peak when a big bossy, well-charged thunder-cloud is on it, to breathe the ozone set free, and get yourself kindly shaken and shocked.” It did convey Muir’s views of the spiritual power of nature, but in the form of “you will” rather than “I did.”

“The sun is setting,” the essay concluded, atop Mount Washburn. “[T]he Absaroka range is baptized in the divine light of the alpenglow, and its rocks and trees are transfigured. Next to the light of the dawn on high mountain tops, the alpenglow is the most impressive of all the terrestrial manifestations of God. Now comes the gloaming … do not let your town habits draw you away to the hotel. Stay on this good fire-mountain and spend the night among the stars. Watch their glorious bloom until the dawn, and get one more baptism of light.”

Changing meaning of public lands

Prose like that helped shape the very genre of nature writing. But the essay is also interesting for its role in the 1890s debates about public land. In 1891 the Yellowstone Timber Land Reserve, now largely the Shoshone National Forest, had been established east of the park—indeed it was controversy over the existence and management of reserves like this one that prompted creation of the 1896 Forest Commission.

Muir wanted the Yellowstone Timber Land Reserve to be an extension of the national park. In his essay, he wrote that Yellowstone “was to all intents and purposes enlarged by the Yellowstone National Park Timber Reserve, and in December 1897, by the Teton Forest Reserve; thus nearly doubling its original area.” The Teton Reserve was actually created in February 1897—effective March 1, 1898—as a result of the forest commission’s work. In coming years, the reserves—eventually renamed national forests—would serve very different purposes from national parks.

But Muir’s essay was part of a grand reconciliation of ideas about public lands, in which he and Gifford Pinchot, eventual founder of the U.S. Forest Service, merged their views of conservation and preservation to support the commission’s goals. For example, although Muir recommended that forest reserves covering Mount Rainier and the Grand Canyon become national parks, he seemed content that logging occur in other reserves.

“Something must be done to preserve and perpetuate the forests, for the timber must ultimately be used,” Muir told an Oregon newspaper. “The forest must be able to yield a perennial supply of timber, without being destroyed. …” In a later Atlantic article, reprinted as Chapter 1 of Our National Parks, Muir discussed the Douglas fir as “admirably suited for ship-building, piles, and heavy timbers in general.” Lodgepole pine was “of incalculable importance to the farmer and miner; supplying fencing, mine timbers, and firewood.”

Together, Muir and Pinchot were arguing that some purposes warranted ongoing federal ownership of land—a radical shift, given that before Yellowstone, the only purpose of federal land was to be given away as homesteads. It was only a decade later, in debates about damming Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy valley, that Muir and Pinchot would vehemently disagree about the conflicting purposes of public land. In the 1890s, they were able to work together to establish America’s public-land birthright.

The naturalist’s legacy

Muir’s reputation as the Father of National Parks rests on two foundations, one specific and one general. Specifically, he was a primary lobbyist for the establishment of Yosemite as a national park in 1890. The Yosemite Valley had been set aside as a California state park in 1864; the donut-shaped national park of 1890 protected surrounding mountains. The two were combined into a larger national park 1906.

Generally, he argued that nature was worth protecting not merely for its resources but for its holistic self, and for the spiritual benefits that humans could gain from appreciating it. When the National Park Service was established in 1916, two years after his death, it largely came to embrace that view.

Muir’s 1885 visit to Yellowstone helped him articulate those values in the context of a national park; his 1896 visit helped him spread that gospel.

Resources

Primary sources

John Muir’s books, including Our National Parks, are available online:

- Chapter 1: The Wild Parks and Forest Reservations of the West: https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/our_national_parks/chapter_1.aspx

- Chapter 2: The Yellowstone National Park: https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/our_national_parks/chapter_2.aspx

Muir’s many articles include:

- “The Yellowstone Park” San Francisco Bulletin, Oct. 29, 1885, p. 4: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb/150

Articles about Muir include:

- “John Muir Is Here,” Portland Oregonian, July 23, 1896

Muir’s letters and journals are online at https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/muir/, John Muir Papers, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library, Copyright 1984 Muir-Hanna Trust. Specific letters and journals quoted in this article include:

- Muir to Louie [Strentzel Muir], Aug 11, 1885, https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmcl/10597/

- Muir to Louie Aug 12 1885, https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmcl/18928/

- Muir to Louie, Aug 14, 1885, https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmcl/9664/

- Muir to Louie, Aug 20, 1885, http://www.oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt3c603237/?order=4&brand=oac4

- Muir journals, August 1885, https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmj-all/1792/

Secondary sources

- Cohen, Michael P. The Pathless Way: John Muir and American Wilderness. Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

- Eber, Ronald. “John Muir and the Pioneer Conservationists of the Pacific Northwest.” In John Muir in Historical Perspective, edited by Sally M. Miller. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., 1999, 195.

- Fox, Stephen. John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement. Boston: Little, Brown, 1981.

- Richardson, Bruce A. "'Fear Nothing': An Interpretation of John Muir's Writings on Yellowstone.” In John Muir, Life and Work, edited by Sally M. Miller. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

- Williams, Gerald W. and Char Miller. “At the Creation: The National Forest Commission of 1896-97.” Forest History Today, Spring/Fall 2005, 32-40.

- Worster, Donald. A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Illustrations

- The photo of Muir in the 1870s is from the Wisconsin Historical Society. Used with thanks.

- The undated photo of tourists on the terraces at Mammoth Hot Springs, from the 1880s judging by the women’s dresses, is from the National Park Service. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Muir on the rock by the lake is from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The view from Mount Washburn, from Muir’s Our National Parks, published 1909, is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The view of Yellowstone Canyon is from Muir’s Our National Parks, published 1909, is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The 1905 photo of John, Louie and Helen Muir is No. MSS048.f24-1348.tif from the John Muir Papers in the Holt-Atherton Special Collections at the University of the Pacific Library. Used with permission and thanks.