- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Quality Vs. Community: The First Century of The...

Quality vs. Community: The First Century of the Wyoming Symphony Orchestra

How do you improve an amateur orchestra? Professionalize it, would seem to be a reasonable answer. But can you do that and still keep longstanding players? Or, if you find ways to bring in better musicians, will longstanding members necessarily be pushed out?

Every community arts organization aiming to raise its standards confronts this dilemma. In the early 1980s, Dox Carr, principal oboe for the Casper Symphony Orchestra since at least 1956, commented, “Assuming the city continues to grow, the orchestra will be full professional, and guys like me won’t be playing anymore. I never thought we’d get that good.” Referring to the current music director, Carr continued, “[Curtis] Peacock cleans house. If somebody out there plays better than the person in the orchestra, he gets the chair.”

But when it all began, there were almost certainly no auditions; therefore, anyone who wished could participate—unless there were, for example, six enthusiastic bassoonists.

The early years: 1925-1942

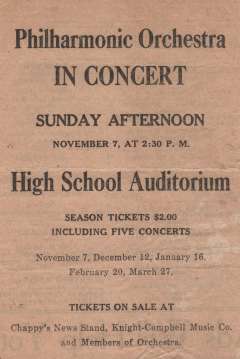

In November 1927, the Casper Tribune-Herald reported, “The Philharmonic Orchestra of Casper will begin its third season of concerts November 28 at the high school auditorium. There will be no admission charge for the concert, or for any of the winter concerts to follow. A group of the leading business and professional men of the city have guaranteed the expenses of the orchestra for the coming season.” The article listed 48 donors.

Nov. 22 of that year, the Tribune-Herald commented, “It is unusual in a city of any size to have an orchestra made up entirely of townspeople. Symphonies of other cities may have a few local people playing, but the important desks, including the director, are usually imported and highly paid musicians. This is not true of Casper.” Another article mentioned that the Casper Philharmonic musicians were not paid.

The 40-piece orchestra played four concerts that season, under the baton of Harry S. Marquis, music director. The first concert drew 1,600 listeners. Among other selections, the orchestra performed the Grand March from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera, Aida.

The Philharmonic continued through the 1930s and into the early 1940s. A May 7, 1934, program shows 32 musicians performing Camille Saint-Saens’s March Heroique, the Romance movement from Henryk Wieniawski’s Concerto in D minor for Violin and Fritz Kreisler’s Lieberfreud. The latter two pieces featured Professor Wade Cramer, solo violin. Other than a song from Georges Bizet’s opera, Carmen, the remaining short pieces were by lesser-known composers. William B. Schilling, who conducted this concert, was music director from 1929-1942.

The Casper Civic Symphony, 1947-1972

Sometime in 1942, early in World War II, the orchestra disappeared from Casper’s musical scene. Natrona County High School music teacher Blaine Coolbaugh returned to Casper after the war and organized the Casper Civic Symphony in 1947, with a Board of Directors. In February of the following year, the orchestra played its first concert—works by Mozart, Schubert and Tchaikowsky—and performed twice more that year. Coolbaugh also initiated tours around the state, and one childrens’ concert per year.

Before 1953, concerts were free, with a few Casper citizens donating the money to cover the orchestra’s expenses. Then the board or Coolbaugh established a maintenance fund, and season tickets also went on sale.

On Jan. 24, 1956, Coolbaugh conducted a concert that included the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 8, op. 93; the overture to Mozart’s opera, The Magic Flute; two pieces by J.S. Bach; Bedřich Smetana’s dances from his opera, The Bartered Bride and a few short pieces by lesser-known composers. The program lists 35 patrons and 62 musicians.

After Coolbaugh resigned, in 1959, the board partnered with Casper College to hire a member of the music faculty who would also conduct the Civic Symphony. Ernest Hagen was hired, and increased the maintenance fund so that the musicians could be paid a small stipend. Hagen also started the Casper Youth Symphony, for advanced high school and college students. This became a feeder system for the Civic Symphony.

Hagen started or revitalized the Symphony Guild, a group of dedicated volunteer women who, aiming to broaden public support, sold season tickets, organized an annual ball to raise money for the maintenance fund and engaged in a variety of activities to finance music scholarships and raise other funds.

The all-volunteer guild had its own board of directors, bylaws and procedures, plus a five-page “Policies and Job Descriptions.” One job was youth symphony chairman, and included aiding the music director with the activities of the group, attending some rehearsals “to check on progress and to know the members” and making concert programs and seeing to their distribution at performances.

When Hagen resigned in 1962, Edmund Marty, brass instructor at Casper College, became music director. Marty started the annual Young Artist Competition in 1968, open to any high school senior who could perform one movement of a concerto. The winner received a small scholarship to the college of his or her choice and performed as a soloist with either the Youth Symphony or Civic Symphony. In at least one instance, the runner-up performed with the Casper College Baroque Ensemble.

Marty was devoted to the Youth Symphony, writing a newsletter for parents, organizing out-of-town tours and, with his wife, hosting social events for the members.

Marty’s programming for the Civic Symphony was ambitious, including the Brahms Symphony no. 4, more than one Beethoven symphony, at least two operas and the Richard Strauss tone poem, Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks. In October 1970, he conducted an all-Beethoven program in honor of the composer’s 200th birthday. He resigned mid-season, and the Beethoven concert may have been his last.

Zoe Brumfield, Marty’s younger daughter, recalled that “Daddy quit the Symphony before he left … Casper College” about three years later. “I think ... he was already looking to leave Casper altogether and trying to decide how to best move on while I was still in [high] school.” Marty and his wife were planning to move to British Columbia, where he planned to serve as a sales representative for the Yamaha Music Company, and as a band clinician for students in that area.

For the 1968-1969 season, the orchestra’s budget was $16,000. The following season, it was more than $18,000.

The 1970s: first push to professionalize

When Marty resigned, Rex Eggleston filled in as conductor. Eggleston was coordinator of the public school orchestra program in Casper and an excellent violist. Casper College hired violinist/conductor Curtis Peacock in fall 1971. Peacock served as assistant conductor for the 1971-1972 season and thereafter was music director—conductor—of the Youth and Civic Symphonies. In 1974, the orchestra was re-named the Casper Symphony Orchestra.

In 1978, Peacock was one of nine candidates selected to work under Dr. Richard Johannes Lert at a clinic in Orkney Springs Va., sponsored by the American Symphony Orchestra League. “Lert sat at a desk right next to the podium and had a large baton that he hit me with,” Peacock recalled. “Once, he hit me on the shins and said, [in heavily accented English] ‘Peacock, what you do this orchestra, the butcher does to the meat with the knife.’” Peacock continued, “Lert was born in 1889, and was my connection with the German Romantic era. I worked hard under Lert and learned a lot.”

In an undated story from the late1970s, the Casper Star-Tribune reported, “Nine years ago, the Casper Symphony Orchestra musicians on stage sometimes outnumbered those seated in the audience. Then, the orchestra’s performers included … a musician who rehearsed with one ear while listening to the latest football scores through an earplug in the other. … In walked Curtis Peacock, selected from a field of 70 applicants.”

Under Peacock, the orchestra improved, but with growing pains. Just a few hours before the first rehearsal of one of Peacock’s earliest seasons, veteran tympanist Douglas Pearce received a phone call informing him that he would no longer be needed. It is unknown who made the call. George Rosenberg, a retired professional and the newly hired piano instructor at Casper College, replaced Pearce.

Something similar apparently happened with Sid Wallingford, the excellent principal cellist, who had served since 1956 or before. Although he continued to play in the section after he was removed from the principal chair, he left the orchestra after a few years and wouldn’t return.

Peacock began holding auditions, initiating the process described by Dox Carr, of selecting the best performers, which sometimes meant rejecting old-timers, competent though they may have been.

The budget grew from $20,700 to about $30,500, mid-decade. Funding was provided by guild activities, the City of Casper, Wyoming Arts Council, Casper Service League and the Tonkin Foundation, among others.

Programming in the 1970s included two Mozart symphonies (40 and 41), four Beethoven symphonies (1, 3, 6 and 7), two Dvorak symphonies (4 and 5), Tchaikowsky’s Fifth Symphony in E minor, The Planets by Gustav Holst, Verdi’s Requiem Mass, and two fully staged operas, Verdi’s La Traviata and Giacomo Puccini’s La Boheme. Holiday favorites were the Nutcracker ballet, featuring various professional dance companies, and Handel’s Messiah, with the Casper Civic Chorale.

Peacock’s high point from the 1970s was performing the Nutcracker ballet with different companies. “The orchestra wasn’t up to it,” he says now, “but would work at it.”

The 1980s: the “core musician” policy

In February 1982, the symphony hired its first full-time professional manager, Kent Steiger. Prior to this, administrative functions were filled by board members or orchestra members. Steiger served for about two years, and was succeeded by at least three other managers through the 1980s.

Peacock, after his first decade, improved the orchestra by hiring professionals for a few key positions, among them concertmaster (principal first violin and head of the entire string section), principal cello and, for a few years, principal bassoon. “I wanted to build a core of professional players who would also teach in the community,” Peacock recalled, and originally envisioned “starting with a string quartet and expanding from there.” But the project didn’t progress beyond concertmaster and principal cello due to funding.

In fall 1981 Peacock hired John Kirk of Billings, Mont., as principal cello. Kirk earned his master’s degree in music from Boston University and also studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, conductor and teacher of many of the great musicians of the 20th century. His addition to the orchestra turned out to be another bumpy transition: The current principal cellist was told nothing about Kirk’s pending arrival, and Kirk had no idea his presence was a surprise to his predecessor.

“I didn’t care for Casper as a place, but I really liked the people,” Kirk recalled. The cello section was nearly nonexistent when Kirk arrived, but he soon built it up, by calling the people who had quit and offering them free private lessons, and also marking their orchestral parts with easier fingerings in case they were uncomfortable with the preferred ones.

For Kirk, the high point of his three years in Casper was all the chamber music he played, mostly piano trios with Peacock and pianist Betsy Taggart. Kirk was “happy to help the community in their grassroots organization.” Peacock, he said, “had a way of getting [solo] artists to come for not very much money and keep them happy while they were here.” Kirk also commented that the orchestra “was not as good as the graduate student orchestra at Boston University, but still pretty good.”

Solo artists during the early 1980s included Peter Rejto, cellist—who flew his private plane to Casper—Mark Kaplan, violinist and Hermann Baumann, french horn. Baumann was such a luminary that the entire french horn section of the Denver Symphony Orchestra drove up to hear him, according to Kirk.

The next core musician position was concertmaster, filled by Randolph Tracy, in 1983. Tracy, serving for three years, was succeeded by James Mothersbaugh, a local violinist and public school teacher. “We had some pretty good players from the public schools,” Peacock commented on Mothersbaugh’s playing.

During the 1980s, funding was provided by the Union Pacific Railroad Foundation and Mountain Bell, among others. The symphony received the Governor’s Arts Award in 1984. The 1985 budget was $196,000; the following year, it was $210,000.

Later on in the decade, it was bust time in Casper and Wyoming’s long-running boom-and-bust, minerals-based economy. Board President Terry Johnson wrote to orchestra supporters in April 1988, “Over the past three years we have reduced the budget substantially to more closely reflect the economy of Casper. We have cut the 1988/89 season to six concerts and do not feel we can make further reductions without jeopardizing the quality of our fine orchestra. Each year the funding received from various government agencies and large corporations has dropped and, therefore, we are becoming increasingly dependent upon individual donors, large and small.”

Sometime during the 1980s, both the Youth Symphony and the Young Artist Competition were discontinued.

The Symphony Guild, however, remained active throughout the decade, with the annual ball and auction its most ambitious project.

The 1990s: enlarging the audiences

Peacock continued as music director throughout the 1990s, and concertmaster and principal cello were still designated core positions. In 1993, the orchestra was re-named the Wyoming Symphony Orchestra.

That year, Dale Bohren became manager. He’d played string bass in the orchestra since the mid-1970s, owned a business and “didn’t see how I could take on another job, even part-time—but I just loved the symphony.” Ironically, his manager duties left him no time for playing in the orchestra.

“There were times when I felt like the little Dutch boy,” Bohren said. “There wasn’t anybody in the office at the time [he was hired], and [Board President] Donna Efimoff drafted me.” The bank account was empty too, with Efimoff and Marta Stroock, another longtime supporter of the symphony, doing their best to run basic operations such as paying the musicians, designing concert programs and getting them printed.

Des Bennion, owner of the Bon Insurance Agency, opened to the Symphony a large, separate room in their building at the corner of Park and 2nd Streets, gave them that space on credit and discounted the rent. Bohren sent a fund-raising letter to past donors, who started coming into the office with checks, or calling to ask what they could do. Betsy Knapp, another strong supporter, came to the office “talking about the music she loved, expressing her gratitude and asking what she could do to help.”

Bohren commented on the three groups he worked with: the board, the guild and the orchestra. “Each of these three thought they were the orchestra. But it takes a lot of people to run an orchestra.” He added, “The orchestra had no idea of fund-raising, the board didn’t understand what musicians did, and the guild was an amazing organ but didn't really work in concert with the other two groups.” However, guild members “were always asking how they could help.”

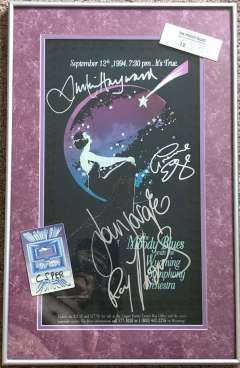

Bohren’s high point from his two years as manager was the orchestra’s 1994 performance at the Casper Events Center with the Moody Blues, the British rock band known for fusing rock with classical music and their hit, “Nights in White Satin.”

“I wanted to get some lift under our wings,” explained Bohren, “and get a popular group, to show a wider audience that the orchestra is fun.”

Engaging the Moody Blues was a Herculean feat of funding. Initially, Bohren discovered that they charged $95,000, which the symphony couldn’t afford. However, after some research, he learned that high-profile groups would perform with an orchestra like the Wyoming Symphony if the group could be guaranteed other performances in the region. For Wyoming, this could include orchestras in Rapid City, S.D., Billings and Salt Lake City.

“In the end, [the band] paid us $7,500 [out of its revenues from the concert], which just about covered our costs, including the Events Center,” Bohren reported. They could afford this because “there was a promotion company that planned and promoted the Moody Blues/symphony concerts across the region. They took the risk. It was a great crowd in Casper and … [the manager] was pretty happy.”

Bohren was in the audience for this performance, along with Sen. Alan K. Simpson, “who still remembers that concert. It was a pops concert on steroids.”

When Bohren left the job in spring 1995 he “felt really good about it. The orchestra was nearly all Casper musicians, and there was a sense of community about it too; in Casper, we can make this happen—and there wasn’t much of a pool to draw from. So many people put a lot into it and did what it took to make it happen.”

Holly Turner, who previously had served as office manager/administrative assistant at the Nicolaysen Art Museum in Casper, took over from Bohren in 1995. The title was then changed to executive director. She and the board continued to build the audience: “The more people in the community we could involve, the more the audience would grow, and people might come to another performance and maybe buy season tickets,” Turner said.

Under Turner, the Moody Blues returned, and the orchestra also performed with American rock bands Kansas, Three Dog Night and Flash Cadillac. There was also a Broadway Nights concert. “The message to the public was that a symphony orchestra concert can be fun,” she said. Fees for these groups could be high, but “we were always happy to break even. We wanted that experience for the donors, the community and the musicians.”

A Beethoven in blue jeans concert let audiences know that a symphony concert didn’t have to be a buttoned-up event. People could wear their casual clothes. “One lady called the office and asked, ‘can my husband really wear his jeans to this concert? I’ve been trying to get him to go to the symphony for years.’”

The various strategies worked, and the audience grew.

The most exciting concert for Turner was Mark O’Connor’s appearance with the orchestra in May 1997. O’Connor, an award-winning country fiddle virtuoso who has collaborated with many classical musicians, had just finished composing his Concerto for Fiddle and Orchestra, which he performed with the symphony. O’Connor improvised his cadenza—the part in a concerto where the orchestra stops playing and the solo instrument plays alone. Improvised cadenzas were common before the 20th century, but then died out. Hence, probably no classical musician or audience member at that concert had ever heard an improvised cadenza. “That concert was magical,” Turner recalled.

Turner’s standout fundraiser was the “Dream Home” raffle, for which realtor Betty Luker donated a lot and general contractor Rocky Eades donated the building services, enlisting all the subcontractors and merchants to discount or donate their services. This included 48 people—architects, roofers, masons, plumbers, painters and more. Ticket sales for the 3,000 square-foot house minus building expenses netted the Symphony about $130,000. The money funded basic operations but was also used to start an endowment for the orchestra.

The orchestra’s budget was between $200,000 and $300,000 while Turner was executive director. By the end of the 1990s, she had served for five years.

The guild continued active in the 1990s and a new organization, Friends of the Wyoming Symphony, participated in some of the same fund-raisers.

Peacock’s high point for the 1990s through 2001 was conducting the Verdi Requiem with the Casper Civic Chorale twice, on March 5, 1994, and April 22, 2001. A requiem is a musical setting of the Latin text of the Catholic Mass for the Dead. Its 15 sections have inspired some of the most dramatic and lyrical music in the entire orchestral repertoire.

2000 to the present: more professionalizing, and a drastic change in orchestra demographics

Peacock’s last season with the Symphony was 2000-2001, which the board devoted to celebrating his 28-year contribution. Turner, still executive director, attended a conductor search conference in Chicago held by the American Symphony Orchestra League. Five finalists auditioned and were interviewed during the 2001-2002 season. The board solicited feedback from the audience, area school teachers and the musicians. “Having conductor candidates was nerve-racking but exciting,” Turner remembered.

She resigned in July 2002, after seven years the longest-serving executive director up to that time. “Although it was very stressful raising money and selling tickets with no computer,” Turner “loved being director of the symphony. I treasured my time and enjoyed the musicians and what they did.” Jennifer Thompson replaced her.

Jonathan Shames was the winning conductor, with his first season 2002-2003. Shames, a world-class pianist, has continued to perform while devoting most of his time to conducting. By the time the symphony hired him, he had conducted orchestras in Washington, Michigan, Boston, Milwaukee and many points abroad. He lived, however, in Ann Arbor, Mich.; in hiring a non-resident conductor, the symphony joined a national trend among community orchestras.

Shames’s non-resident status changed the orchestra and how it was run. Under Peacock, rehearsals before the concert began with a Monday evening string sectional, then five more rehearsals over the two weeks before the Saturday evening concert. Imported musicians arrived the day before, and played the Friday evening and Saturday afternoon rehearsals. They were generally paid more than resident orchestra members and were housed in private homes, the latter practice continuing through most of the early 2000s.

Since Shames wasn’t available for the two weeks before the concert, the entire schedule was compressed into a long weekend, Thursday through Saturday. There was one rehearsal Thursday, two on Friday and, as before, a Saturday afternoon rehearsal followed by the concert that evening. Sometimes there was a Sunday matinee. Imports arrived on Thursday, so all the rehearsals included the whole group. This schedule was more demanding for the locals. They had less time to assimilate their parts into the whole, and little time, if any, to practice between rehearsals.

Gradually, as local positions were vacated, more imports were added—mostly to the woodwinds and brass—until, by October 2007, the orchestra was half Colorado musicians. However, the Feb. 11, 2006, concert featured four local soloists.

Programs from mid-decade reveal a tactful effort to educate and encourage the audience. They included notes on how a concert begins; sounds that get in the way; good concert manners; instruments of the orchestra along with a seating chart; and a glossary of musical terms.

In another innovation, “Musical Conversations,” Shames led a series of informal discussion on the history of the upcoming concert repertoire. These were on Thursdays of concert weekends at the Natrona County Public Library.

Shames’s last season was 2007-2008; three new candidates were auditioned that season. The winner was Matthew Savery, music director of the Bozeman (Mont.) Symphony.

The budget, meanwhile, climbed from $295,000 in 2001 to more than $350,000 by mid-decade. Funding was provided by the Wyoming Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Wyoming State Legislature, the City of Casper and numerous businesses and individuals.

Kate Tiernan was Executive Director from 2009-2012. Circumstances had deteriorated; there was nobody in the office when she took the position, and she received no training. The orchestra was then $55,000 in debt and concert attendance was down. Tiernan reorganized the office and moved it to its current location at 225 S. David, where the building’s owner, Peter Wold, charged the symphony half rent for the first few years.

“It took three years to turn things around,” Tiernan said, but at the end of that time the organization was in the black and the orchestra was reconnected to the community.

Her high point occurred near the end of her time as executive director, with the dress rehearsal for the April 4, 2012, concert. Russian violinist Alexander Markov was the guest artist. He and the orchestra had to rehearse in the Natrona County High School band and orchestra room because a high school talent show was using the auditorium. After the rehearsal, Tiernan offered to show Markov the hall he’d be performing in and, when he discovered why the auditorium hadn’t been available, offered to play for the students and judges. “He played a Paganini excerpt and it was beautiful,” Tiernan recalled.

Rachel Bailey became executive director in July 2012, after having served on the board for the previous year and a half. She is now the longest serving director in the orchestra’s history. She took the job because she “felt that my marketing and business skills could help the orchestra." Although the organization was in the black, it was still struggling financially.

During her tenure, the board and Bailey have focused on “really serving the community,” she said, an effort which has grown significantly in the past 10 years. Through Music on the Move, the symphony provides transportation for senior citizens to concerts and visits assisted living centers and the schools, to “encourage young musicians to continue their studies.”

A Young Artist competition for Wyoming students was initiated in 2014, and is held every two years. There are two separate categories, high school and college, and the winners perform with the symphony.

The orchestra’s finances are currently the most secure in its history, with an endowment fund, a planned giving program and a reserve fund. For the past five years, the budget has been approximately $500,000.

In the past ten years, the administrative structure that includes import musicians has changed. After passing an audition, musicians become regular members of the orchestra and are paid regular orchestra pay plus mileage, a per diem and hotel expenses. Imports are now rarely housed in private homes.

Bailey’s high points so far are “lots of fun things,” she says, such as the 2017 eclipse concert in Washington Park, held on the weekend of the August 2017 total solar eclipse and drawing 2,500-3,000 people. There have since been more “Pops in the Park” concerts. Bailey also mentioned a 2013 production of Tchaikowsky’s ballet, Swan Lake, the first sold-out performance in years, and a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth that same year, involving the Casper Civic Chorale and the Casper College choir.

Repertoire in the 20-teens, noticeably more advanced than in past decades, has included difficult and beautiful works such as the Tchaikowsky Serenade for Strings and Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Not even an excellent community orchestra is likely to be able to handle these pieces, and certainly not on four rehearsals with no real practice time between rehearsals. This is evidence that the caliber of the symphony has significantly improved over the past 20 years.

The board

Traditionally the symphony board raised money for the orchestra, and performed many administrative functions before a professional manager was hired in 1982. With the expansion of the executive director position plus paid office staff, more basic management and grant-writing has shifted to the office, leaving the board freer to pursue community service, community relations and fundraising.

The late Donna Efimoff served on the board perhaps longer than anyone else, with Terry Johnson a close second. Beginning in the early 1970s and extending into the late 2000s, Efimoff was president at least three times. Along with her husband, the late Alex Efimoff, she hosted many visiting musicians and also gave frequent, lavish post-concert receptions for patrons, guest artists and the orchestra. The Efimoffs were also longtime season ticket holders and generous financial donors. Efimoff was honored in the 1991-1992 symphony season brochure, the summary of her contributions concluding, “[A] major note of thanks to the best friend an orchestra ever had.”

Dr. Valerie Inella Maiers, Casper College art history instructor, has served on the board for the past 10 years. She reports that the board is charged with “advocacy, representing the orchestra to the public and maintaining a complete financial picture, which includes ensuring appropriate use of funds and planning for the future.” Maiers also mentioned “friend-building” and a related term, “friend-raising:” pairing an evening of food and socializing offered through ticket sales to the public, by which the board builds the relationships that lead to successful fund-raising.

A high point for Maiers occurs at “almost every concert, when there is a moment, whether or not I am familiar with the music—a ‘goosebumps’ moment—when I realize that I am so fortunate to be here in Casper to experience it, and envision that the orchestra might be here to pass on to my children.”

Dr. Eric Unruh, dean of the Casper College School of Fine Arts and Humanities, chaired the most recent music director search committee. The committee first met on Nov. 13, 2017, shortly after Savery announced to the board that he would be resigning at the end of the 2017-2018 season.

Unruh began by having the committee review the mission and goals of the symphony to answer the question, Who are we and what do we want to be? Unruh said that “this focused the entire search.”

Through two rounds of sorting, the committee selected 10 candidates from the initial pool of 100 applicants. They interviewed these 10 via Zoom, with “carefully selected questions,” according to Unruh, including a prior agreement among themselves “not to be swayed by personalities or achievements but to answer the question, ‘who’s the best fit for us?’”

The board was “comfortable with all four finalists,” who each spent a week in Casper rehearsing the orchestra, touring the college and Natrona County High School, where the orchestra performs. Each gave a pre-concert talk as well. As with previous finalists, the audience, musicians and search committee were all surveyed for their feedback.

Unruh’s high point was at the end of the search, a year and four months after the first meeting. “The day the committee made the decision was euphoric because we were unanimous.” He added, “Making the decision by the search committee was not difficult, and not binding on the board,” which did follow the committee’s recommendation. “Everybody was very pleased with the process.”

The winning candidate was Australian Christopher Dragon, who is still, as of fall 2021, music director. He also serves as resident conductor for the Colorado Symphony.

The musicians

Rebecca Mothersbaugh, from Bethlehem, Pa., has a bachelor of fine arts degree in violin performance from Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh. She became concertmaster of the Wyoming Symphony Orchestra in 1994, and is the longest-serving concertmaster in the orchestra’s history. She has played in orchestras in Caracas, Venezuela; San Juan, Puerto Rico, Shreveport, La. and Cheyenne, Wyo. An experienced Suzuki violin teacher, Mothersbaugh has taught at the University of Wyoming summer music camp and maintains a private studio in Casper. Mothersbaugh could not be reached for an interview.

Carolyn Deuel has played in the percussion section since 1976. Deuel majored in piano performance and also studied mallet percussion. She has played almost all the percussion instruments in the orchestra, including glockenspiel, xylophone, chimes, vibraphone, celeste, bass drum, triangle, tambourine and cow bells. The high point of her time with the orchestra so far has been a performance of the Brahms Requiem sometime in the late 1990s, for which Deuel sang in the Casper Civic Chorale. “I thought the orchestra played very well,” Deuel commented.

In 1996, Richard Turner joined the orchestra as principal bassoon. Turner got his bachelor’s degree in bassoon performance, subsequently became a computer programmer and settled in Casper. On March 6, 1999, Turner was soloist in the Mozart Bassoon Concerto with the orchestra.

Commenting on the changes he’s observed in his 25 years with the orchestra, Turner has noticed the “radical transition away from a Casper-centric orchestra” to the present point where the board [and Dragon] want to “have a regional asset and not to be a Casper vehicle for cultivating musicians.” Nurturing community musicians has gone “nearly by the wayside.”

According to Turner’s personal knowledge, of 10 woodwind positions, two are locals. Of 11 brass players, one is local. Most of the non-local woodwind and brass are from Colorado. Deuel reports that the percussion section is all locals except the tympanist, who is from Denver. Susan Stanton, a 27-year veteran of the violin section, notes that as of the 2020-2021 season, 14 string players out of a total of 36 were from Casper. These figures add up to an orchestra that is much less than half Casper players.

Turner’s answer to the problem of excluding qualified local musicians is to have two rounds of auditions, a locals round, then a non-locals round, “with the understanding that Casper winners would be competent but probably not as good as a graduate student in the region.”

His high points so far have been his Mozart performance, and Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat (The Soldier’s Tale), performed in January 2015 with Dr. William Conte and students from the Casper College department of theater and dance narrating and acting. It was “great, because it’s a piece I’ve always loved.”

Turner also treasures concerts with the Casper Civic Chorale, “because this includes some of my favorite pieces like the Verdi Requiem and Beethoven’s Ninth.”

Nearly a century of evolution

Nearly 100 years ago, the Casper Philharmonic played the opening concert of its first season. Nobody was paid, the programming was modest and the musicians were all from Casper. Funding was ad hoc and hand-to-mouth.

Civic pride continued and community involvement increased. The orchestra expanded, including a handful of import musicians from other cities in Wyoming and occasionally a few from Colorado. Often the latter had Casper roots.

Hardworking, talented high school and college students were funneled into the orchestra via the Youth Symphony. Even in the early 2000s, two decades or more after the Youth Symphony folded, students were still playing in the orchestra.

In the humble, more frugal 1960s, for solo artists the symphony relied heavily on University of Wyoming music faculty, many of whom were excellent performers. As the budget expanded, the orchestra could afford world-class soloists for most seasons.

All through its history, the orchestra has been sustained by volunteers: the guild, the board and, at the beginning, the musicians. It adds up to tens of thousands of hours donated to foster live music in Casper.

With the huge increase in out-of-state import musicians, all of whom are designated and paid as regular members of the orchestra, plus the change in rehearsal schedule, the dilemma of how to improve the orchestra without excluding qualified locals appears to have been resolved in favor of quality. The orchestra’s mission statement says, “The Mission of the Wyoming Symphony Orchestra is to enrich the cultural lives of adults, expand the musical horizons of children, and provide an outlet for the creative talents of musicians living in Wyoming and the Rocky Mountain West.”

At least through the mid-2000s, the last clause read, “provide an outlet for the creative talents of musicians living in Wyoming.” Indeed, some of the remaining, and best, Casper musicians are truly home-grown: The principal second violinist and principal violist played in the symphony in high school in the 1990s when students were still being included. One cellist, serving since the 1970s, also played in the symphony while in high school. Another, Casper born and bred and now living in Laramie, played in the symphony in high school and college. The skill and experience these musicians gained are still enriching the group.

The Wyoming Symphony enjoys broad and generous support from the community; many local foundations and a long list of businesses and individuals contribute to the orchestra each year. This provides concerts of unprecedented quality for Casper residents, who only have to travel across town to hear their semi-professional orchestra.

Resources

Interviews

- Bailey, Rachel. Telephone interview with the author, Sept. 8, 2021.

- Bohren, Dale. Telephone interview with the author, Aug. 18, 2021. Emails to the author, Sept. 9, 10 and 20, 2021.

- Brumfield, Zoe. Email to the author, Aug. 13, 2021.

- Deuel, Carolyn. Telephone interviews with the author, Aug. 19, 2021, Sept. 16, 2021.

- Hein, Rebecca. Personal recollections.

- Kirk, John. Telephone interview with the author, Aug. 18, 2021. Email to the author, Aug. 27, 2021.

- Maiers, Valerie Inella. Telephone interview with the author, Sept. 21, 2021.

- Peacock, Curtis. Telephone interview with the author, Aug. 28, 2021.

- Stanton, Susan. Emails to the author, Sept. 23, 2021.

- Turner, Holly. Telephone interview with the author, Aug. 23, 2021.

- Turner, Richard. Telephone interview with the author, Aug. 24, 2021, Sept. 16, 2021. Emails to the author, Aug. 28, 2021, Sept. 3, 2021.

- Unruh, Eric. Telephone interview with the author, Sept. 17, 2021. Social media message to the author, Sept. 20, 2021.

- Knapp, Mrs. George (Elizabeth). “Casper Symphony Orchestra.” In Craven, Robert R. Symphony orchestras of the United States: selected profiles. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986.

Newspapers.com. Available to patrons at the Natrona County Public Library, Casper, Wyo.

- Casper Star-Tribune, June 30, 1960, Nov. 28, 1965, Aug. 8, 1968, Aug. 6, 1969, April 13, 1977, April 16, 1977, March 2, 1979, May 2, 1982, March 7, 1990, Nov. 19, 1992, Aug. 22, 1993, March 18, 1996, March 20, 1996, March 5, 1999, Nov. 20, 2009.

Wyoming Symphony Archive (private, uncatalogued archive)

- Most of the written sources for this article are contained in the Wyoming Symphony Archive, and include Symphony Guild scrapbooks, Board meeting minutes, concert programs and newspaper clippings. Many of the latter are unidentified and undated. Others are from the Casper Journal: Oct. 4, 1986, Oct. 28, 1989, Nov. 11, 1989, April 2, 2008; Casper Tribune-Herald: Undated from 1926, Nov. 20, 1927, other undated clips, November 1927; Casper Star-Tribune, March 17, 1974, Oct. 31, 1974, Jan. 17, 1975, May 9, 1975, Feb. 19, 1982, Aug. 18, 1982, Aug. 28, 1982, Feb. 6, 1983, May 13, 1983, Sept. 2, 1983, April 28, 1984, Feb. 26, 1985, Sept. 20, 1985, Sept. 22, 1985, Nov. 21, 1985, Sept. 24, 1989, Oct. 29, 1999.

- Many thanks to the Wyoming Symphony Orchestra for lending its archives to WyoHistory.org, to those who generously gave their time for interviews and emails, and to the Natrona County Library for assistance with Newspapers.com.

Illustrations

- The Moody Blues poster belongs to Dale Bohren. Used with permission and thanks.

- All the rest of the images are from the archives of the Wyoming Symphony Orchestra. Used with permission and thanks.