- Home

- Encyclopedia

- John Hunton and His Diaries of The Wyoming Fron...

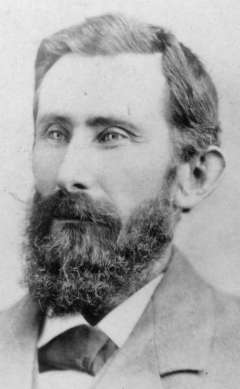

John Hunton and his Diaries of the Wyoming Frontier

John Hunton was born at Madison Courthouse, Va., on Jan. 18, 1839, of Alexander B. and Mary Elizabeth (Carpenter) Hunton. Little is known of his childhood. He joined the U.S. Army at age 18 and saw his first military service at Harper’s Ferry in 1859.

Madison was in that borderland between the North and South where the cleavage of loyalties split families, set brother against brother and father against son. Hunton chose the South. He was with Pickett at Gettysburg and served with the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia until Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

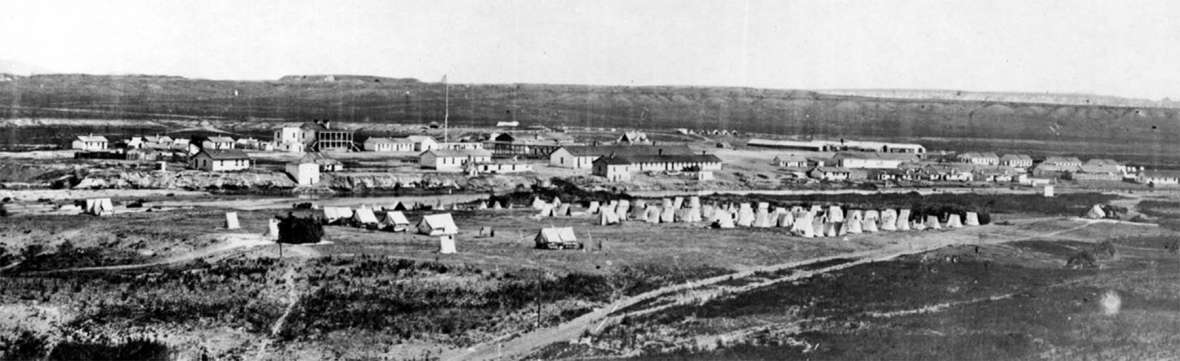

With his homeland overrun and devastated, John Hunton turned his eyes westward and in the spring of 1867 traveled, via St. Louis and Glasgow, Mo., to Nebraska City. From there he whacked bulls on to Fort Laramie, in what would become Wyoming Territory the next year. Fort Laramie was the bastion of the plains and headquarters for military operations against the Lakota Sioux and other tribes. There he worked for several years as a clerk in the Sutler’s store at the old fort, which was to be “home” for the young Virginian for most of the rest of his life.

Upon his arrival, Mr. Hunton shared a room with the famous scout, Jim Bridger, who had been employed by the government to guide our Army’s troops. They occupied the northeast corner room of the Sutler’s building, made of adobe bricks and understood to be the first permanent structure in what is now the state of Wyoming.

In 1870, Hunton took a contract to supply Fort Laramie with firewood, and his government contracts expanded steadily during the next 10 years into big business for that period. In addition to wood, he supplied hay, beef, charcoal, lime and other commodities to Fort Fetterman and Camp McKinney as well as to Fort Laramie, and hauled freight with oxen from Medicine Bow Station to Fetterman, Fort Steele, Fort Phil Kearney, Fort Reno, Fort Smith and other early military installations. In 1871 he became half owner, in partnership with W. G. Bullock, of the SO cattle, understood to be the first herd in this area, aside from work oxen. This herd, according to Hunton, was started in 1868 by a man named Mills who brought the stock from northern Kansas.

On Jan. 1, 1875, Mr. Hunton began to tell in his own words the day-to-day story of his life and experiences in diaries that spanned more than half a century. The books in which Mr. Hunton kept his early journals deserve a few words. From 1875 until 1900, they are almost identical in form and quality. A physical description of the 1875 diary should suffice for all.

The book is 3 x 6 inches in size and solidly bound with a double leather cover. The outside cover has weathered to a deep brown; the inside one retains its natural light-tan freshness and has two leather pockets, front and back. When the double flap of the outside cover is tucked into its slot, the entire book is well protected against weather and rough treatment when carried in a man’s pocket or saddlebag, as this one certainly was on many a rugged journey.

The pages are gold-edged, unfaded, crisp and full of “life” and made of paper built to withstand the effects of water. Hunton made his entries with both ink and pencil, depending apparently on whether he was at home or camped on the trail. And not a leaf in the book is loose from the binding. We do not believe many present-day papers or bindings possess the same lasting qualities. The diaries are now permanently housed at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center in Laramie as part of the Hunton and Flannery collections.

The diaries tell a many-sided story of the cattle industry since its inception in Wyoming; the last of the Indian wars; the passing of the stagecoach and the building of the railroads; the disaster of the 1880s which spelled the end for the early cattle barons; range wars and homesteading; the gradual development of irrigation, farming and modern ranching; of history, politics and government. And Hunton was located in the middle of it all. He ran a ranch and road ranch for many years at Bordeaux, on Chugwater Creek on the main road from Fort Laramie to Cheyenne, about seven miles southeast of present Wheatland, Wyo.

The diaries also tell a tale of life’s unceasing frustrations for one who seeks perfection—of how a strong man’s hopes and ambitions were gradually dimmed and dulled to death by the inexorable years. Mr. Hunton bequeathed the diaries to his good friend L. G. "Pat" Flannery, who between 1956 and 1963 published the entries from 1873 through 1882 in four volumes of 1500 copies each. Two more volumes with entries between 1883 and 1888 were published after Flannery’s death in 1964. In addition to these daily diary entries, Mr. Flannery also included narratives by Mr. Hunton and others in these books, and his own painstakingly researched commentaries, to clarify and expand upon events of that period.

As a result, the publications vividly preserved day-to-day life on the frontier and presented profiles as well as true exploits not only of people living in that era who have been all but forgotten, but also of such well-known Western folk characters as Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane Canary, Buffalo Bill Cody, Generals Custer and Crook, Red Cloud, Spotted Tail and many others, most of whom Mr. Hunton personally knew.

Hunton was the last post trader at old Fort Laramie. He was one of the first and also one of the last commissioners of Laramie County when it embraced the present counties of Goshen and Platte. Most of the early settlers in that area proved up on their homesteads under his authority when he was a commissioner of the U.S. land office from 1892 to 1907. As a civil engineer, largely self-taught, he participated in the original survey of north central and western Wyoming when it was mostly an uncharted wilderness area, and he planned and surveyed many of the earliest private reservoirs and irrigation systems in southeastern Wyoming.

John Hunton passed away in 1928. He was a gentleman of strong character and integrity—one of the most accurate historians of his time who left behind him monuments of accomplishment in many fields.

Editor’s note: This article is adapted from the opening pages of The Diaries of John Hunton: Made to Last, Written to Last, an abridged version of the diaries compiled by Mr. Flannery's grandson, Michael Griske, and published by Heritage Books in 2005. Mr. Griske donated the original diaries to the American Heritage Center in Laramie, Wyoming. Special thanks to Mr. Griske for the adaptation.

Resources

- Griske, Michael, and L. G. Flannery. The Diaries of John Hunton: Made to Last, Written to Last: Sagas of the Western Frontier. Westminster, Md.: Heritage Books, 2005.

- “Jack Hunton Tells of Stirring Scenes When State Young: Pioneer Stockman Recalls Tragedies and Triumphs when Bordeaux Was Important Cross-Roads.” Wyoming State Tribune, June 26, 1921, accessed Dec. 20, 2021, p. 9, at https://pluto.wyo.gov/knowvation/app/consolidatedSearch/#search/v=list,c=1,q=title%3D%5BBordeaux%5D%2CqueryType%3D%5B16%5D,sm=s,sb=1%3Atitle%3ADESC,l=library7_lib,a=t

Illustrations

- The photos of John Hunton and Pat Flannery are from the author’s collections. Used with permission and thanks.

- William Henry Jackson’s 1870 photo of Fort Laramie is from the United States Geological Service’s Denver Library Photographic Collection. Used with thanks.