- Home

- Encyclopedia

- A Brief History of Heart Mountain Relocation Ce...

A Brief History of Heart Mountain Relocation Center

During World War II, people of Japanese descent from Oregon, Washington and California were incarcerated at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Park County, Wyo., as the result of an executive order of President Franklin Roosevelt. Residents were at the camp from Aug. 12, 1942 to Nov. 10, 1945, two months after the end of the war with Japan. When the camp was at its largest, it held more than 10,000 people, making it the third largest town in the state.

Japanese Americans Prior to World War II

Much of the immigration to the United States from Japan began in 1884 when thousands of Japanese arrived in Hawaii to work the sugar cane fields. In the wake of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, drastically restricting Chinese immigration, Japanese people began arriving on the mainland of the United States to work as laborers on railroads, farms and in mines. Many of the more prosperous immigrants started small businesses or became farmers. While most settled along the West Coast, roughly 13,000 people of Japanese descent lived in the Intermountain West prior to World War II.

Like many prior immigrant groups, the Japanese faced discrimination. Starting in the early 20th century, Japanese immigrants, as well as Chinese immigrants, were targeted by Alien Land Laws in western states including Wyoming. These laws prevented the acquisition of land by Asian immigrants. In 1924, the U.S. Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act, which all but cut off new immigration from Asia. In response, Japanese Americans formed organizations such as the Japanese American Citizens’ League to help address their shared challenges. Despite the attempts of Japanese Americans to assimilate, nativist groups expressed ongoing skepticism regarding the place of Asians in American society.

Incarceration Follows Pearl Harbor

The Heart Mountain Relocation Center was one of ten facilities constructed to confine 120,000 Japanese Americans removed mainly from West Coast states. Following the initial roundup of individuals of German, Italian and Japanese descent deemed threats to national security after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Department of War recommended further detainment of all individuals of Japanese descent living in a swath of land that encompassed most of Washington and Oregon, all of California and southern Arizona.

To manage the movement and incarceration of such a large population, a new agency called the War Relocation Administration (WRA) was created. Ten sites for relocation centers were selected by April 1942. California, Arizona and Arkansas hosted two centers each, while Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming each contained one center.

The case for mass removal was built by military leaders and West Coast politicians. Describing a January 27 conference with California Governor Culbert Olson, General John De Witt stated that the residents of California “are bringing pressure on the government to move all the Japanese out. As a matter of fact, it’s not being instigated by people who are unthinking, but by the best people of California.”

In spite of public support, the relocation of Japanese Americans was not popular with many living near the potential confinement sites. In Wyoming, Gov. Nels Smith warned that the state “will not stand for being California’s dumping ground.” Smith said that the Japanese should be kept under armed guard “and be removed at the end of the emergency.” While some in Wyoming, like Powell Tribune editor Raymond Baird, welcomed the additional laborers the camp would bring to the region, many viewed the project instead as a necessary patriotic burden in support of national security.

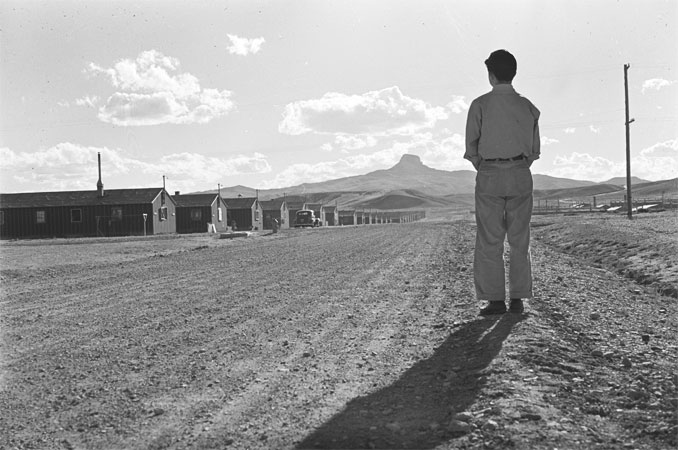

Life at Heart Mountain

The first internees arrived at Heart Mountain on Aug. 12, 1942. The facility consisted of 450 barracks, each containing six apartments. The largest apartments were simply single rooms measuring 24 feet by 20 feet. Perhaps the most easily identifiable features of the barracks were the tarpaper exteriors. While each unit was eventually outfitted with a potbellied stove, none had bathrooms. Internees used shared latrines. None of the apartments had kitchens. The residents ate their meals in mess halls.

When the people first arrived, a barbed-wire fence to surround the camp was not yet complete. The internees protested the construction of this barrier and caused further work to be delayed. In November 1942, they submitted a petition containing 3,000 signatures to WRA Director Dillon Meyer.

The fence was completed by December, however, and further emphasized the sense of confinement among the internees. Shortly after the construction of the fence, 32 boys were arrested for sledding in the hills beyond the boundary. In response to the perceived overreaction on the part of the camp administration, Rikio Tomo, a Heart Mountain internee, placed an editorial in the Heart Mountain Sentinel asking for clarification about the internees’ citizenship status and constitutional freedoms.

To accommodate the young, schools were built at Heart Mountain, including a high school completed by the fall of 1943. These schools served students from elementary school through high school. Roughly 1500 students attended Heart Mountain High School, which included grades 8-12.

The internees provided most of the labor required to run the Heart Mountain camp, while the WRA administrators oversaw its general operations. Wages ranged from $12 per month for unskilled labor to $19 per month for skilled labor, including teachers for the schools and doctors in the camp hospitals. In addition, Heart Mountain internees also worked as manual laborers on farms and ranches in Wyoming and nearby states from Nebraska to Oregon.

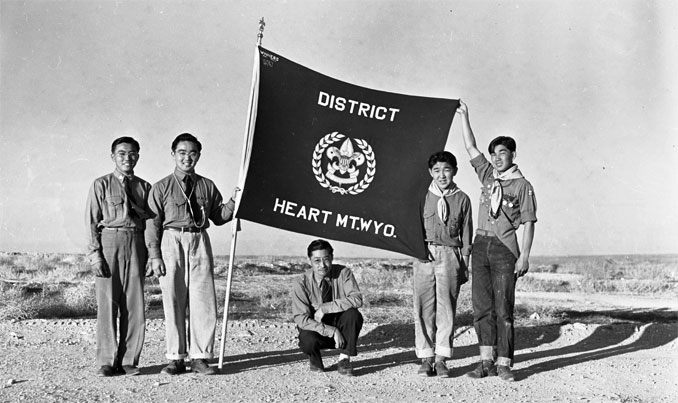

The WRA administrators encouraged activities emphasizing American civics, such as scouting and adult English classes, as part of what they saw as an Americanization process. Committees composed initially of American-born internees provided much of the day-to-day governance of the camps. While these groups provided some measure of self-determination, they disrupted the generational hierarchy. American-born adults in their 20s and 30s were given a higher political status within the camps than their Japanese-born parents.

Within the camp at Heart Mountain, internees participated in a number of activities including theatrical and musical performances, Christmas celebrations, sporting events and festivals. Many events, particularly those with Japanese origins, required approval from the project director. One popular event was Obon Odori, a festival celebrated each summer in many Japanese American communities.

Reactions to the Relocation Center

Reactions to the presence of internees at Heart Mountain inspired a number of different responses. While L.L. Newton, editor of the Wyoming State Journal, expressed outrage over the disregard for the constitutional rights of American-born Japanese, others, like Wyoming’s Republican U.S. Sen. E.V. Robertson, felt the internees were living too luxuriously at the expense of taxpayers.

Interactions between internees and local residents, though rocky at times, were largely peaceful. While the camp was in existence, many internees frequented stores in nearby Cody and Powell, Wyo. while on temporary leave and supplied labor to area farms and ranches. Temporary work leave provided opportunities for internees to earn better wages than those offered within the camps. After the high school was built, local varsity sports teams entered through the barbed wire perimeter to play games against the Heart Mountain Eagles.

The biggest controversy stemmed from the suspicion that the WRA coddled internees, who were accused of hoarding resources while the American public was subject to rationing. In February 1943, Earl Best, a steward working at Heart Mountain, reported to the FBI that internees working in the camp mess halls were hoarding food. After the FBI failed to follow up on the lead and Best was dismissed from Heart Mountain, he told his story to the Denver Post. The newspaper published a series of scathing articles. The story, along with the help of Sen. E.V. Robertson, led to a congressional investigation by Rep. Martin Dies, a Democrat from Texas and chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

One of the more outlandish statements made to the press regarding the Dies investigation came from Rep. Joseph Starnes, Democrat of Alabama, who claimed Heart Mountain internees received “prime beef and five gallons of whiskey apiece.” To combat these allegations, the WRA invited reporters to visit Heart Mountain in August 1943. The journalists from Montana and Wyoming found little that resembled the luxurious conditions described by Robertson, Starnes or the Denver Post. While the Dies Commission failed to yield any substantive actions against the camp, its investigation reflected the continuing suspicions circulated on a regional and national level.

The Heart Mountain 63

The organization of draft resistance distinguished Heart Mountain from the other relocation centers. In 1943, General George Marshall approved the creation of Japanese-American combat unit. The plan, which was given the endorsement of President Roosevelt, was to create an all-Japanese regiment, consisting of soldiers from a previously existing Hawaiian unit and volunteers from the camps. The response from within the camps fell far short of expectations, partly because of a loyalty questionnaire distributed by the WRA. As a result of the low turnout, the War Department extended the draft to the camps.

The WRA form was used to determine eligibility for military service and permanent leave. Many of the questions were considered intrusive by internees. Others were not as straightforward as the WRA probably intended. Instead of serving as a neutral tool to determine someone’s suitability for service, the questionnaire further alienated many internees. For example, question 27 asked about a person’s willingness to serve in the military. For internees who felt service should be contingent upon the restoration of constitutional rights to all Japanese Americans, a simple yes or no answer was insufficient.

In each of the camps, the draft became a divisive issue. While some internees felt military service was an opportunity to exemplify patriotism, others felt that constitutional rights should be restored before agreeing to mandatory service.

At Heart Mountain, a group called the Fair Play Committee advocated for civil disobedience. These draft resisters refused to report for pre-draft physicals and were charged in a federal court. In all, 63 individuals were tried in Cheyenne for draft evasion—the largest mass trial in Wyoming history. In June 1944, after this group was found guilty, leaders of the Fair Play Committee were tried in Cheyenne for counseling others to evade the draft. They were found guilty as well in November 1944.

The 63 draft resisters were sent to either McNeil Island Penitentiary in Washington State or Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas. All seven leaders of the Fair Play Committee were sent to Leavenworth. The 63 draft resisters were sentenced to three years, while the 7 leaders were sentenced to either 2 or 4 years depending upon their perceived involvement. In December 1945, the conviction of the Fair Play Committee was overturned based on a technicality. President Truman pardoned the 63 draft resisters in 1946.

But after the initial protest, draft resistance largely faded. The Army sent a tail gunner named Ben Kuroki on a tour of the camps to help the recruiting effort. Kuroki, a native of Nebraska, enlisted in the military shortly following Pearl Harbor. By the end of World War II, 385 Heart Mountain internees had been inducted into the military. During the war, 11 were killed and 52 wounded.

Redress and Remembrance for Internees

The lifting of the West Coast ban in January 1945 spurred evacuation of the relocation centers. By Nov. 10, 1945, the last internee left Heart Mountain. In the decades immediately following the war, the incarceration was seldom discussed in the public sphere. In 1969, a group of Japanese American activists that included former internees embarked upon the first annual pilgrimage to Manzanar Relocation Center in Southern California. This annual remembrance helped spark a dialogue within the Japanese American community. It moved the topic from a private arena shared among individuals and within families into a more public arena.

In 1980, the U.S. Congress formed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. The subsequent investigation included the testimony of 750 witnesses and a Congressional report published in 1983 titled Personal Justice Denied. Finding the incarceration to be unwarranted, the report recommended an official apology be made as well as redress payments of $20,000 given to survivors of the camps in addition to the creation of an education fund to increase public awareness about the camps.

One particular event at the Heart Mountain camp had profound ramifications decades later. During World War II, a troop of Boy Scouts from Cody met with a troop from Heart Mountain and led to the introduction of Norman Mineta and Alan Simpson. Many years later, when Mineta was representing his California district in the U.S. House of Representatives and Simpson was representing Wyoming in the U.S. Senate, the two sponsored the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. In 1988, President Ronald Regan signed the legislation, enacting into law the recommendations in the earlier report.

Grants awarded from the public education fund include monies used for preservation of documents and artifacts from the Relocation Centers currently held in museums, libraries and archives. The Civil Liberties Act also funded restoration and construction of buildings dedicated to the memory of the Heart Mountain center, including the transfer of one of the barracks to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles and the construction of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center on the site of the original camp, about halfway between Powell and Cody.

Resources

- Baldwin, Chad, “Another lesson from Heart Mountain,” Casper Star Tribune, Aug. 22, 2011, accessed May 21, 2013, http://trib.com/opinion/columns/another-lesson-from-heart-mountain/article_44ae19b9-8071-5659-a58d-9740112c980a.html.

- Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Public Law 100-383.

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982.

- Densho Organization, “Densho – Archive,”accessed May 23, 2013 at http://www.densho.org/archive/default.asp for its oral histories and digitized copies of the Heart Mountain Sentinel.

- Frank Abe collection of oral histories about draft resistance at Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Densho Organization Archive, accessed June 14, 2013 at http://archive.densho.org/archive/default.asp.

- Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. "History – Life in Camp." accessed June 14, 2013 at http://www.heartmountain.org/history.html.

- "Heart Mountain Digital Preservation Project." Hinckley Library, Northwest College, Powell, Wyo., accessed June 6, 2013 at http://www.northwestcollege.edu/library/special/hmdpp/.

- Ishigo, Estelle. Lone Heart Mountain. Los Angeles: Anderson, Ritchie, & Simon, 1972.

- Mackey, Mike, ed. A Matter of Conscience: Essays on the World War II Draft Resistance Movement. Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2002.

- ___________________. Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays of Japanese American Internment in Wyoming. Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 1988.

- Manbo, Bill and Eric L. Muller. Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Nelson, Douglas W. Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp. Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin for the Department of History, University of Wisconsin, 1976.

- Simpson, Alan. Shooting from the Lip: The Life of Senator Alan Simpson. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 19-21.

- Tomo, Rikio. “Block Officer Urges Efforts Toward Rehabilitation of Evacuees.” Heart Mountain Sentinel, December 5, 1942, accessed June 12, 2013, http://archive.densho.org/Core/ArchiveItem.aspx?i=denshopd-i97-00105.

- Walz, Eric. “Japanese Settlement in the Intermountain West, 1882-1946.” In Guilt By Association: Essays on Japanese Settlement, Internment, and Relocation in the Rocky Mountain West. Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2001, 1-24.

Illustrations

- All photos are from the George and Frank C. Hirahara Photograph Collection, 1943-1945, Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries, Pullman, Wash. Used with permission and thanks.