- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Baseball, Politics, Triumph and Tragedy: The Ca...

Baseball, Politics, Triumph and Tragedy: The Career of Lester Hunt

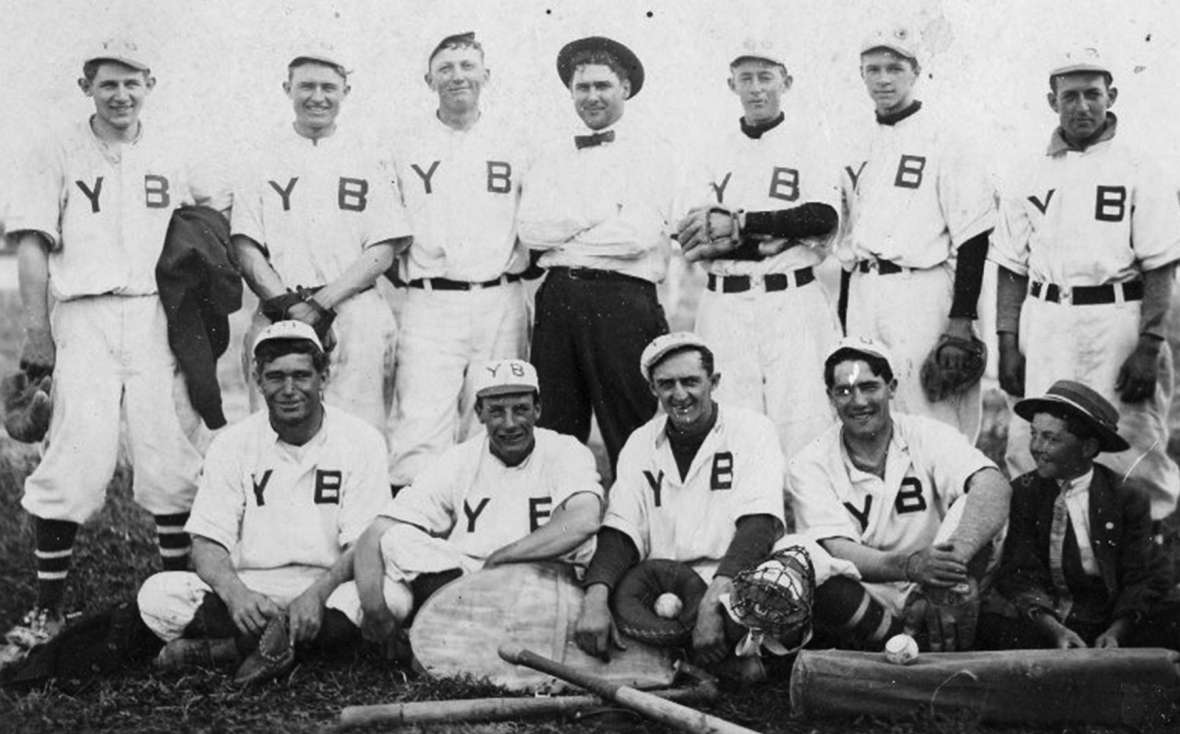

“Stee-rike three,” the umpire cried, waving his right arm in the air with the call that brought Lester Hunt to Wyoming. Young Hunt had just thrown a no-hitter, rare for the Central Illinois Baseball League.

The news of Hunt’s accomplishment traveled quickly the 1200 miles from Atlanta, Ill., to Lander, Wyo. Baseball was big in the central Wyoming community. Lander’s team had just lost its star pitchers. Jim “Death Valley” Scott and “Greasy” Farthing had signed with the majors and were now pitching “lights out” for the Chicago White Sox. Told of that no-hitter, Coach Ikey Thomas set out to recruit the Illinois star.

Thus, Lester Hunt’s Wyoming story started on a Lander baseball diamond soon after he stepped off the train in June 1911. Over the years, he moved from being a fan favorite on the field to a beloved country dentist and on into politics. Though a Democrat in a decidedly Republican state, Hunt never lost an election, winning a seat in the state legislature, twice elected secretary of state and governor before voters sent him to the United States Senate.

Ironically, the effort of his widow to cover up the facts surrounding his tragic suicide may also have obscured his extraordinary legacy.

Practicing dentistry

The perseverance he demonstrated as an athlete showed in other aspects of his life. The dean of Washington University denied Hunt’s application to attend its College of Dentistry, believing Hunt could not succeed while working full time on the railroad, a job he needed to fund his education. Hunt confronted the dean, explaining his circumstances. An impressed dean was convinced this young man could do whatever he decided to.

After serving in the Army during World War I, Hunt returned to Lander with his new bride, Emily Nathelle Higby, opened a dental practice and started a family. Daughter Elise was born Dec. 30, 1921. Lester Hunt, Jr., nicknamed “Buddy, arrived six years later.

Politics

Dr. Hunt’s short dental career launched his political career. Colleagues elected him president of the Wyoming Dental Association, a position demanding he lobby and entertain many of the state’s politicians. That opened the door to relationships that served him well later. But a family health crisis hastened the transition from dentistry to politics.

When four-year-old Buddy was diagnosed with bone cysts in 1931, doctors at Rochester’s Mayo Clinic suggested bone grafts. Four grafts were accomplished using bone from his father’s shin. Hunt found it necessary to “shift from the toothaches of dentistry to the headaches of politics.” When the procedure rendered him unable to stand for long periods, as a dentist must, Lester Hunt stood for election, winning a seat in the Wyoming State House of Representatives in 1932.

There he earned a reputation for doing his homework and making his case eloquently and persuasively. He was recruited by party leaders to run for statewide office. In 1934, Hunt was elected to the first of two four-year terms as secretary of state.

Republican Nels Smith was nearing the final year in his first term as governor when World War II broke out. A veteran, Hunt was angered by what he saw as Smith’s failure to take a wartime governor’s role seriously. He was irked when Smith cut the state’s civil defense budget by 62 percent. In a letter among Hunt’s official papers, he accused Smith of “Not cooperating with the Fed. Gov. in helping to build up an Army,” when the incumbent governor recommended “only two weeks’ pay to men called into service.”

During a Jefferson Day speech, Hunt charged Smith with failing to lead on the war effort and assured voters he would cooperate fully with Roosevelt. Using a baseball metaphor, Hunt said Governor Smith’s “final score reads, ‘no runs, no hits, many errors, a lot of foul balls, and the state left holding the saxs (sic).” Hunt was elected governor in 1942.

Wartime governor

In Gov. Hunt’s initial State of the State speech to the legislature, he referred to the 18,000 Wyoming men and women then serving in the armed forces, a number soon to grow to 25,000. Hunt told lawmakers, “It is our patriotic duty to leave no act undone that will assist our Commander-in-Chief, our army and our navy, in every possible way to bring about a rapid and successful conclusion of this war.”

The lives of even small-state governors revolved around the war. Hunt’s days were filled with tasks ranging from managing fears of Japanese attacks and the Selective Service to rationing, war bond drives and planting victory gardens. Official files from his governor years are replete with letters, speeches and other documents reflecting how much of his time Hunt spent as a “war-governor.”

State governors bore the heavy responsibility of managing the Selective Service Act. Hunt recruited a state director for the program. More difficult was recruiting people to serve on local draft boards. Legislation implementing the draft built a web of standards by which the local draft boards decided who among their neighbors’ children went to war and who stayed home. The inevitable community-level controversies led to a constant turnover in local draft boards.

“Complaints come to me daily with reference to every draft board in the state,” Hunt wrote a constituent. There were complaints about personalities, partisan composition and the size of the boards, and whether veterans’ organizations were adequately represented. Some felt the boards gave too many deferments. Others complained there were too few.

More difficult emotionally were the requests for draft deferments. Old friends pleaded for deferments for sons. Many requests came from farmers or ranchers who needed their boys to work the land, others from employers struggling to keep their businesses alive despite staff shortages. One letter spoke for them all. “I understand the Army needs men but we need it (sic) here on the home front too.” Gov. Hunt took time to gracefully respond to each letter, never evidencing that he felt “put upon” in handling a request.

Handling Heart Mountain

Managing the controversies arising from FDR’s decision to locate a Japanese-American relocation camp in Wyoming was far more complex. Hunt’s predecessor, Nels Smith, made this job much harder by stirring anti-Japanese feeling. Smith and other Wyomingites agreed Japanese-Americans should be imprisoned—just not here. Still others saw an opportunity to use them for slave labor on their farms and ranches.

Taking his cue from Smith’s rhetoric, one Wyoming rancher offered to dunk Japanese-Americans in a dipping vat. “We use an arsenic dip and for Japs,” he wrote Gov. Smith, “we will step it up to straight arsenic.” Lester Hunt’s predecessor responded, “It is most heartening to have the support of reasonable people on decisions of this character.”

Smith learned of FDR’s decision to locate a camp in Wyoming nearly a year before losing the governorship to Hunt. Smith’s immediate reaction was to notify U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle that Wyoming would not accept “these Japanese into our state.” Even to his last breath as governor, Smith warned that “if the Japanese-American were permitted to remain in Wyoming following the war,” there would be “a serious social problem.”

By the time this political hot potato was handed off to the new governor, the pot had been stirred and was boiling over. Over the next few years, Hunt mediated disputes between the towns of Cody, Wyo., and Powell, Wyo., over whether the nearby Heart Mountain internees should be treated as POWs or allowed to shop in their communities. The governor parried disinformation offered by Wyoming U.S. Senator E.V. Robertson and others, including former Gov. Smith, who insisted without evidence that Robertson had been assured the Japanese-Americans would be required to leave Wyoming when the war ended.

Hunt was assisted by camp director Guy Robertson (no relation to Sen. E. V. Robertson). When the Powell Chapter of American War Dads petitioned Hunt to “not impose these people on the Fathers and Mothers of this community at a time when many of them are being advised of the deaths of their sons and daughters in our war against Japan,” the governor turned to Guy Robertson for an answer.

In a letter to Hunt, Robertson responded that the petition may have been “instigated” by “some fanatical, race baiting, unthinking and unprincipled individual. . . . Seven-hundred-fifty-eight boys from families in Heart Mountain are now fighting in our armed forces all over the world, and I venture to suggest that these boys are just as dear to their War dads and mothers as are the boys from Powell or any other community to theirs.”

Robertson said that some “sober reflection” could cause those who signed the petition “to hang their heads in embarrassment and shame.” The fact that Hunt passed the camp director’s harsh assessment along to those who had sent him the petition is an indication that the governor shared Robertson’s sentiments.

The war ended. Hunt was elected to a second term as governor by a wide margin, though Republican candidates won the other four statewide contests. Although the Republican Party dominated Wyoming politics, Democrat Hunt had become the most popular politician in the state.

Nonetheless, Lester Hunt felt unfamiliar political headwinds as he contemplated a run for the U.S. Senate in 1948. Republican Arthur Crane was secretary of state and would become governor should Hunt be elected to the senate. Disgruntled Democrats began promoting primary opponents for Hunt. Among them was Scotty Jack, who won seven statewide elections before being defeated in a run for governor in 1954. Others encouraged Thurman Arnold, a well-known Laramie attorney, to run against Hunt.

Soon, recalcitrant Democrats accepted Hunt’s candidacy. However, to win a seat in the Senate, Hunt had to survive both a lawsuit claiming he could not run for the Senate while serving as governor, and President Harry Truman’s unpopularity. When the dust cleared, Hunt had defeated Robertson, the incumbent, with a comfortable 57 percent of the vote; Truman won as well.

Battling McCarthy in the Senate

Fortuitously, Senator-elect Hunt and his wife escaped Wyoming a day ahead of the historic Blizzard of ’49 and arrived in Washington during a political storm. Arthur Schlesinger called it “the Age of Suspicion.” Sen. Joseph McCarthy was becoming McCarthyism.

Hunt and the Wisconsin senator clashed when the Wyoming freshman was appointed to a special Senate committee charged with investigating whether German soldiers, accused of war crimes at the Battle of the Bulge, were coerced into confessing and denied their legal rights. Although not a member of the committee, McCarthy insinuated himself into the proceedings. According to David Oshinsky’s biography of McCarthy, the Wisconsin senator “bullied witnesses, exaggerated evidence, and turned almost every session into a barroom brawl.”

Those hearings were Lester Hunt’s introduction to Joe McCarthy. The two disliked each other immediately. Later, Hunt introduced legislation allowing private citizens to sue members of Congress who libeled them, a direct attack on McCarthy. He called his Wisconsin colleague “a drunk and a liar.” The stage was set for a deadly confrontation.

Hunt worked in the U.S. Senate with the same intensity as he did every political office he held. His abilities led to an appointment to the Special Committee on Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce. Hunt went toe-to-toe with some of the most infamous crime figures in the country. Committee chair Sen. Estes Kefauver, impressed with his Wyoming colleague, told friends Hunt would be his running mate if he won the 1952 Democratic Party nomination for president. The senator from Wyoming wrote one of the early health care proposals that became Medicare.

Suicide

In what started the longest year of Lester Hunt’s life, Buddy was arrested in June 1953 for soliciting homosexual sex in Lafayette Park across from the White House. Buddy was tried and convicted. Joe McCarthy, and Senate President pro tempore Styles Bridges, R-New Hampshire, and Sen. Herman Welker, R-Idaho attempted to use that information to blackmail Hunt into resigning from the Senate so that Wyoming’s Republican governor could appoint a replacement.

On the morning of June 9, 1954, night fell on Lester Hunt’s life when he went to his Senate office and shot himself. Former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson said decades later that what happened to Hunt “passed all boundaries of decency and exposed an evil side of politics.”

Given the enormity of stigma tied to both suicide and homosexuality, his widow, Nathelle, fought against the telling of the story for the remainder of her life. The original manuscript of T.A. Larson’s History of Wyoming included the entire sordid account. When Larson showed Mrs. Hunt the manuscript, she hired attorney J.J. Hickey, a powerful Democrat. Hickey threatened a lawsuit if Larson proceeded. Accordingly, Larson’s history, used to teach thousands of Wyoming’s high school and college students, simply said on page 520, “On June 19, 1954, Senator Lester Hunt, overwhelmed by political and personal problems, committed suicide.”

For nearly three decades, that was all that was known about Sen. Hunt’s death. Those who knew remained silent. Because that story was not told, few were aware of the political accomplishments of this extraordinary public servant.

Events explaining Hunt’s suicide were eventually revealed and are chronicled elsewhere. They need not be repeated here. While Lester Hunt will be remembered for the events that led to his death, he deserves also to be remembered for his remarkable political career, one punctuated by decency, honesty and public service.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Abell, Tyler, ed. Drew Pearson Diaries. New York, Chicago, and San Francisco: Holt, Reinhart and Winston,1974, 319, 321.

- Bridges, Styles. Papers of Styles Bridges. New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, N.H.

- “Dr. Hunt to be candidate for Governor.” Wyoming State Tribune, May 14, 1942, 1, copy at Wyoming State Archives.

- House Journal of the Twenty-seventh State Legislature 1943. Governor’s Message, 26, copy at Wyoming State Archives.

- “Hunt takes over as governor.” Wyoming State Tribune, January 4, 1943., copy at Wyoming State Archives.

- “Kefauver Reported Favoring ‘only’ Senator Hunt for VEEP.” Rawlins Daily Times, May 6, 1952, 13, Wyoming State Archives.

- Larson, T. A. Papers. Collection No. 400029, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo. (Hereafter AHC)

- Lester C. Hunt Papers. Collection No. 00270, AHC.

- Pearson, Drew. “Welker Threatened Hunt’s Son With Trial—Pearson,” Laramie daily Bulletin, June 23, 1954, 16.

- Selective Service Act Regulations. Section 120, Vol. 1, Sept. 23, 1940.

- Smith, Nels S. Papers. Collection No. 09880, AHC.

Secondary Sources

- Ewig, Rick. “McCarthy Era Politics: The Ordeal of Senator Lester Hunt.” Annals of Wyoming 55, no. 1, (Spring 1983), 9-21, accessed Jan. 8, 2021 at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom55121983wyom/page/n7/mode/2up. This was the article that first made public the circumstances around Hunt’s suicide. It’s also the article that first piqued the author’s interest in the topic.

- Johnson, David. The Lavender Scare. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2004, 140-141.

- Kiepper, James J. Styles Bridges: Yankee Senator. Sugar Hill, N.H.: Phoenix Publishing, 2001, 145-146.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 520.

- __________. The War Years. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming Historical Foundation, 1954, 61.

- McDaniel, Rodger. Dying for Joe McCarthy’s Sins: The Suicide of Wyoming Senator Lester Hunt. Cody, Wyo.: Wordsworth, 2013, xi, 86, 244-303.

- Oshinsky, David M. A Conspiracy So Immense. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, 76-77.

For further reading and research

- O’Gara, Geoffrey. “The History Lesson of Lester Hunt: What happens when government polices sex.” Wyofile, June 25, 2015, accessed Jan. 8, 2021 at https://trib.com/lifestyles/home-and-garden/a-death-untold-the-suicide-of-wyoming-sen-lester-hunt/article_68e7c2e9-cec0-557b-bf53-1b5db00ea88e.html. Thoughts about Hunt’s death in the context of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on same-sex marriage.

- Storrow, Benjamin. “A Death Untold: The Suicide of Wyoming Sen. Lester Hunt.” Casper Star-Tribune, April 14, 2013, accessed Jan. 8, 2021 at https://trib.com/lifestyles/home-and-garden/a-death-untold-the-suicide-of-wyoming-sen-lester-hunt/article_68e7c2e9-cec0-557b-bf53-1b5db00ea88e.html. A recap of events surrounding Hunt’s death, on the occasion of a 2013 mock trial in Cheyenne of Hunt’s blackmailers, played by actors, at the time of the publication of the author’s biography of Hunt.

Illustrations

- The photos of Hunt with his Senate staff, Hunt with O’Mahoney and President Truman and of Hunt’s body lying in state are all from Wyoming State Archives; the coffin photo is from the Brammar Collection. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Sen. McCarthy, Jean McCarthy, Sen. Bridges, Deloris Bridges and Hunt is from the New Hampshire Division of Archives and Records, Concord, N.H. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the baseball team is from the Fremont County Pioneer Museum in Lander, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.