- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Nineteen Camps: World War II POWs In Wyoming

Nineteen Camps: World War II POWs in Wyoming

“Greeting for Santa Claus”

O Santa Claus, now we greet thee,

Who can but come from Germany,

We greet thee in a troubled time,

Who in the great folk-strife afar

The dear old German Christmas feast

Must spend as prisoners of war.

The above poem was written by an anonymous World War II prisoner of war at Camp Dubois, Wyoming. Translated by Lowell A. Bangerter.

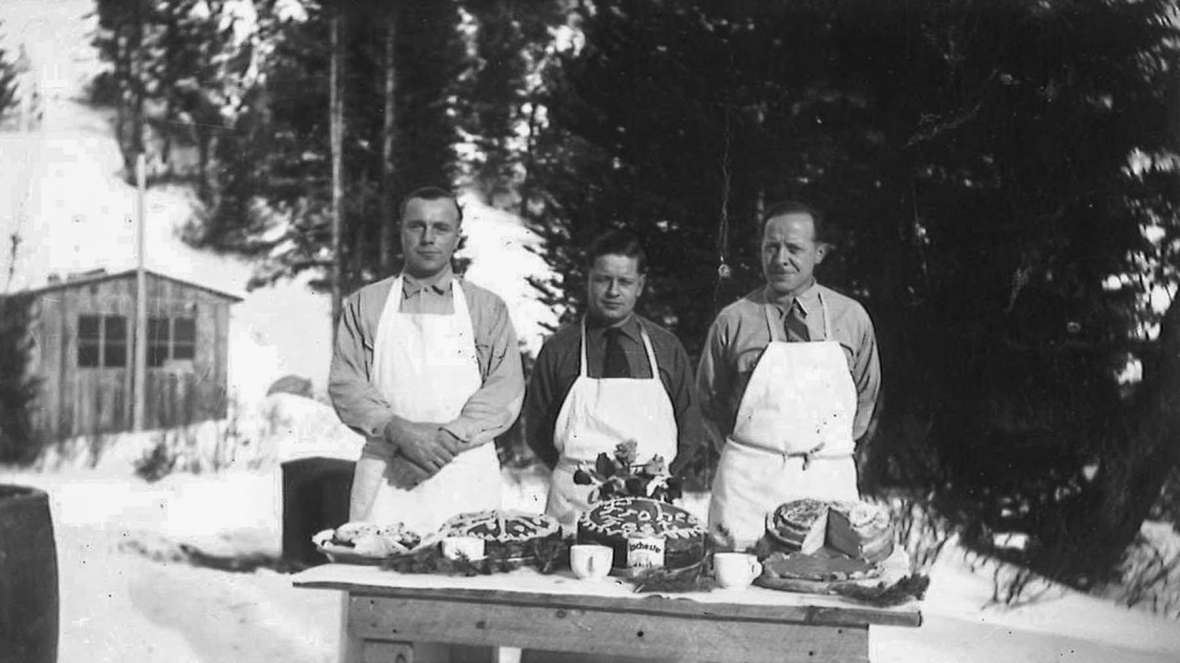

Christmas Eve at a POW camp

Three feet of snow fell at Christmastime, 1944, on a small, isolated prisoner of war timber camp near Dubois, Wyo. Prisoners and Army camp staff were snowbound together for several days. On Christmas Eve, POW Rudolf Ritschel noted, they all “celebrated together quite according to German custom. The men on both sides were deeply impressed by the entertainment presentations.”

Lt. Harold Harlamert, commander at Camp Dubois, provided details about the Christmas program the POWs put on in their mess hall, a program he said was “exceptionally good.” The prisoners set up a special table for the American personnel too and shared their Christmas items and foods with them. The POWs even provided typed, printed programs which included acts and poems that teased several POWs and U.S. military personnel.

A small orchestra performed Christmas music, Harlamert noted, and the prisoners sang German Christmas songs; the YMCA provided the instruments. A special Christmas tree lighting was included. The U.S. Army camp interpreter “acting as Santa Claus for them” cut out big “PW” letters and pinned them on his back. The prisoners got a “big kick out of this” because they were required to wear “PW” letters on their clothes. Harlamert recalled that “among the gifts that Santa distributed were a bunch of letters addressed to the PWs that had just come in from their homes in Germany.”

Operation of World War II POW camps

During World War II, approximately 436,000 prisoners of war were held captive in the United States. The U.S. operated 155 large POW base camps and 511 branch camps across the country. Prisoner of war camps were established in every state except Vermont. In addition, there were POW camps in the U.S. territories of Alaska and Hawaii.

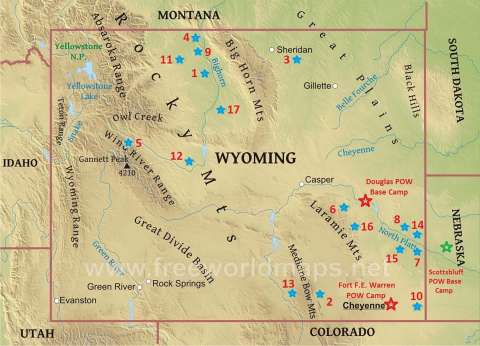

Nineteen World War II prisoner of war camps operated in Wyoming. Prisoners included Italian, German, Austrian, Czechoslovakian and Polish soldiers. The first POW camps in Wyoming were established in 1943. The two main POW camps were at Camp Douglas and Fort Francis E. Warren in Cheyenne. Prisoners at Fort Warren were generally confined to the military base. Camp Douglas and Camp Scottsbluff, Neb., base camps provided prisoners for many smaller branch camps in Wyoming.

Seventeen branch camps were established in Wyoming to provide seasonal agricultural and timber labor, critically needed due to war-related labor shortages. Agricultural branch camps operated at Basin, Deaver, Lovell, Powell, Worland, Riverton, Clearmont, Wheatland, Lingle, Torrington, Veteran, Huntley and Pine Bluffs, with prisoners working primarily in the sugar beet, potato and bean fields. Timber camps operated at Dubois, Esterbrook in the Laramie Range above Douglas, Ryan Park in the Snowy Range east of Saratoga, and Centennial.

Relations among prisoners and between prisoners and guards were generally good, but there still was a war on. In camps housing Germans, especially at the larger camps such as Camp Douglas, there were problems associated with the strong Nazi leadership. Extreme pro-Nazi leaders harassed and even attacked non-Nazi POWs. When camp officials were alerted to potentially dangerous prisoners or safety concerns, they added security, including segregation of hostile prisoners. At Camp Douglas, a German noncommissioned officer was found hiding in the attic of an old camp building. It was reported that he was hiding from pro-Nazi camp leaders. Afterward, additional security measures were taken, including the use of guard dogs and the installation of double fences around the prisoner compounds.

The camps were administered by the U.S. Army regional service commands, which operated under the Army Service Forces and Provost Marshal General’s Office, in accordance with U.S. War Department policies. In 1942 there were nine service commands established in the United States. Wyoming was part of the Seventh Service Command. Prisoners were transferred across state lines between base camps and branch camps within their regional service command.

POW Labor Program

In January 1943, the U.S. government authorized the use of POW labor on military installations. A program to make prisoner labor available to civilian employers was implemented the following fall through the cooperation of the War Department, the War Manpower Commission and War Food Administration. POW branch camps were set up to provide prisoner labor more efficiently to area farms and timber operations.

Civilian employers worked with local military officials and the Department of Agriculture’s Extension Service to use prisoner of war labor. The POW Labor Program benefitted local industries and provided substantial revenue for the U.S. Treasury. The farmers and logging companies paid for the POW labor at rates equal to what they would have paid local civilians. It was a necessity for the employers, even though they had to pay, because the prisoners’ labor was so desperately needed. By June 1945, contractors had paid $22 million into the U.S. treasury for POW labor.

POW labor achievements and recognition

State, county and other agricultural and timber industry groups appreciated and acknowledged the importance of the prisoners’ work. Both the agricultural and timber industries were labor intensive.

A Camp Douglas POW named Guethe wrote that the work on the farms was unfamiliar and therefore difficult for many of them. However, he said their accomplishments “were recognized by the American army and civilians, as we read with pleasure and satisfaction in our last camp newspaper.” In September 1945, Director Albert Bowman, Wyoming Agricultural Extension Service, wrote to Gov. Lester Hunt that Wyoming’s labor requirements for agriculture would not have been met without the prisoners of war.

Geneva Convention guidelines

The Geneva Convention of 1929 specified that prisoners were to be “at all times humanely treated and protected.” Officers were exempt from physical labor and received the same pay they were previously entitled to. Non-commissioned officers were only required to perform supervisory work. For each day they worked, enlisted prisoners were paid 80 cents, in scrip, with which they could purchase items in the camp canteens. Many POWs saved part of their pay to take home with them after the war. One former Camp Veteran POW reported he had saved “close to a thousand Marks” by the time he returned to Germany.

The Geneva Convention provided that prisoners were not allowed to do “unhealthy or dangerous work,” and their daily hours could not be excessive. POWs were allowed one day off per week, “preferably on Sunday.”

Construction and operation of the POW camps also followed Geneva Convention guidelines. In Wyoming, six POW branch camps used former Civilian Conservation Corps camps and modified the barracks for prisoner use. Other camps modified existing buildings, constructed temporary buildings or housed camp residents in tents. The U.S. military staff and POWs had separate mess halls and sanitary facilities.

Food shortages

Geneva Convention guidelines also specified that the food rations of the prisoners “be equivalent in quantity and quality” to that of the U.S. Army personnel at the camps. However, food and other shortages in the U.S. led to rationing and revised menus as the war progressed, including significant changes at the Wyoming POW camps.

In 1945, a food conservation program was implemented nationwide to help build up U.S. food reserves depleted by the needs of the armed forces. For that purpose, but also to help refute charges that the Army was pampering the prisoners, the War Department reduced POW menus of meat and other foods in short supply. In addition, many people believed the new food policy at the camps was in response to late-in-the-war discoveries of Germany’s poor treatment of American prisoners—and of the concentration camps.

Changes for the prisoners in Wyoming included substitutions and reductions in meat rations and in dairy products (margarine instead of butter, for example), especially after the war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945. According to POW camp documents, a U.S. Army colonel from the Medical Department from Omaha, Neb., made a tour of all the branch camps in Wyoming during the summer of 1945 to check on health problems and the food adequacy for the prisoners of war.

The food shortages led camp officials and prisoners to use alternatives to meat. According to Camp Dubois Commander Lt. Harlamert, by September 1945, “chicken was served about once a week,” but there was “no beef or pork in the POWs’ rations and very little of the other meats.”

Harlamert reported that the prisoners resorted to trapping to supplement their food supply; game included porcupines, snowshoe hares and grouse. Prisoners shared a “generous sample” of porcupine meat, he noted, including “a front leg and a piece of liver,” prepared by POW cooks the same way his mother used to fix hasenpfeffer, a traditional German stew made with rabbit. He remarked that “it was a delicious dish” and he “enjoyed it very much.”

Former POW Johann Pilhofer shared memories of his time as a Camp Dubois prisoner in a 2017 interview. He said that the guards shot wild game even though they knew it was poaching and there was a penalty if they got caught. The guards shared venison and other meat with the prisoners. The prisoners helped to process the game in the camp kitchen.

U.S. enlisted men at Camp Dubois also found ways to supplement their own and their officers' rations, catching fish in nearby lakes and streams. Harlamert said the Army staff enjoyed fresh fish about three times a week when conditions were favorable.

Civilian employers supplemented the POWs’ food, even though it was not required and often specifically discouraged. Many Wyoming residents of Italian and German heritage shared common customs and food preferences with the prisoners they employed. Employers often prepared special meals or snacks for the POWs working on their farms and in the timber camps to show their appreciation for the prisoners’ hard work.

A farm family that employed POWs to work in their sugar beet fields southwest of Lovell treated the prisoners with compassion, even though they had lost their son during the war. The prisoners were served strawberries mixed with “precious rationed” sugar and cream for dessert. The POWs lined up, bowed and said “danke” after they finished eating. Some local farmers even brought prisoners to their homes for Sunday dinners.

POW camp life

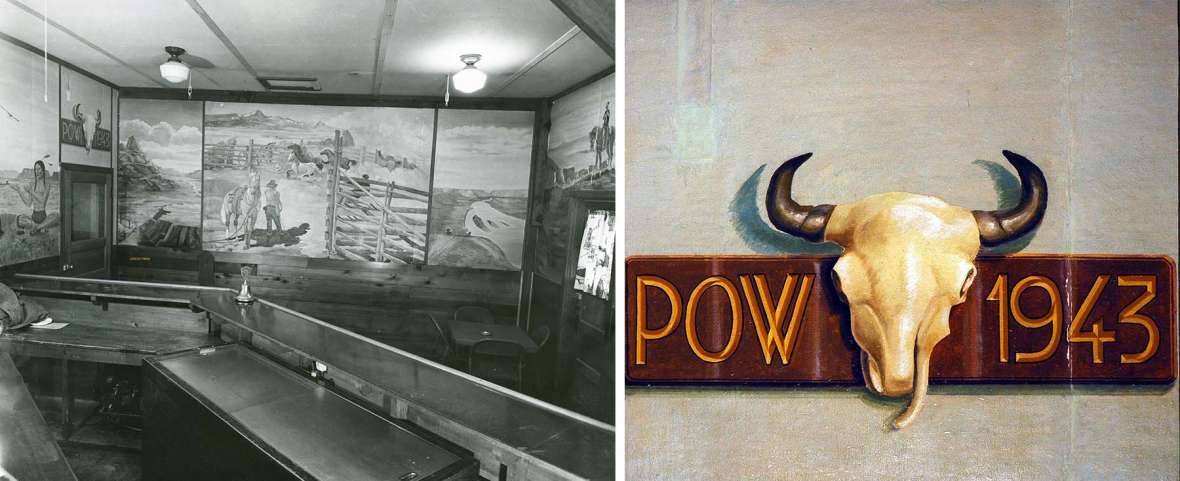

The “organization of intellectual and sporting pursuits by the prisoners of war” was also encouraged by the Geneva Convention. The prisoners took part in many activities during their free time, especially at the base camps. They played musical instruments, performed in theatrical presentations, watched movies, read books from the camp libraries, played sports and took a variety of courses. Religious services were also provided at many of the camps. A Camp Douglas POW wrote that the camp activities gave structure to their free time and helped many of them overcome homesickness.

The prisoners wrote essays, poems, memoirs and correspondence, sharing firsthand accounts of their everyday lives as prisoners of war. They expressed concern over their families, homeland and hopes for the future, and many of their essays and poems were shared in the POW camp newspapers. They also created murals, sketches, paintings, wood-carved items and sculptures as outlets for their thoughts and perceptions. The Western-themed murals painted on the walls at the Camp Douglas Officers’ Club State Historic Site are examples of Italian POWs’ art.

Cultural exchanges occurred between the POWs and many of the people they came in contact with. Close relationships sometimes developed among the prisoners, the U.S. Army personnel and local employers. Several prisoners made gifts for their new Wyoming friends or to show their appreciation to employers for their kindness while working on farms or in the timber camps. At a recent presentation about Wyoming POW Camps, a woman brought a plaque of the Blessed Mother, made by an Italian POW, to share with the audience. The prisoner gave the plaque to the woman’s father, who had served at Camp Douglas as an interpreter to the Italian prisoners there.

Wyoming camps finally close

The Wyoming POW camps continued operating for several months after the war ended with Japan’s surrender Sept. 2, 1945. Agricultural branch camps stayed open until the fall harvests were completed. Some branch camps operated into early 1946. Fort Frances E. Warren was the last Wyoming POW camp to close in late April 1946.

Conclusion

In postwar interviews and correspondence with local residents, former Wyoming prisoners of war said that they appreciated being treated humanely and fed well. Former Corporal Fritz Hartung returned to Wyoming in 1975 to visit a former POW camp site he was assigned to. He reported that he was never mistreated or ridiculed. Cesare Oriano, a Wyoming POW from Camp Douglas and Fort Warren, returned to Cheyenne to live after the war. Oriano related that the Italian prisoners were treated with respect and dignity.

The successful operation of the Wyoming POW camps and labor program was an important part of our state’s World War II history. The significance of our Wyoming POW camps extends well beyond documenting the 19 former POW camp sites. It involves learning about the daily lives of the prisoners and military personnel that worked in the POW camps. It includes understanding how Wyoming civilians were often involved in the daily operation of the camps. It also includes recognizing the importance of POW labor for the timber and agricultural industries, and the labor achievements by the prisoners of war.

The cultural exchanges and close relationships that developed between the groups were fostered during the operation of the Wyoming POW camps. The stories told by U.S. Army personnel, prisoners of war and local employers provide a personal glimpse into the experiences they shared. People worked together to overcome wartime challenges, and treated each other with tolerance and respect.

Resources

Primary Sources

- “Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Geneva, July 27, 1929.” International Committee of the Red Cross, accessed Oct. 26, 2021 at http://www.icrc.org/ihl/305.

- Goodrich, Gary. Telephone interview and written correspondence with author, Aug. 29, 2018.

- Hansen, Ruthanne Hill. Telephone interview with author, Sept. 25, 2018.

- Harlamert, Harold. Written Correspondence and POW reports, 1944-1946.

- Institute for the Study of War and Democracy. National World War II Museum, New Orleans, Telephone and email communication with author, Oct. 8-9, 2021, nationalww2museum.org.

- Offe, Marian Testolin. Oral and written interviews with author, Jan. 28, 2020, Feb. 26, 2020, Oct. 21, 2021.

- Pilhofer, Johaan. Written and Skype interviews with author, March 21, 2017, April 6, 2017.

- Stutz, Paul. Oral History Transcript, World War II POW, Interviewer Barbara Allen, Wyoming State Museum, May 20, 1993. Wyoming State Archives.

- Thompson, Ellen Oriano. Written communication with author, April 15, 2018.

- U.S. War Department. “Prisoner of War Camp Labor Report,” Camp Dubois, Wyoming 1944-1946. Office of the Provost Marshal General. National Archives.

- YMCA Reports, Harold Hong. “Report on Visit to Prisoner of War Branch Camp (Scottsbluff), Veteran, Wyoming,” Dec. 18, 1944. National Archives.

Secondary Sources

- Bangerter, Lowell A. “German Prisoners of War in Wyoming.” Journal of German-American Studies 14, no. 2, 1979, 96, 108-109, 120.

- Kirkpatrick, Kathy. “POWs in the USA-10 Surprising Facts About America’s WW2 Prisoner of War Camps.” Military HistoryNow.com, accessed Nov. 23, 2021 at https://militaryhistorynow.com/2018/04/10/pows-in-the-usa-10-amazing-facts-about-americas-ww2-prisoner-of-war-camps/.

- Krammer, Arnold. Nazi Prisoners of War in America. Briarcliff Manor, New York: Stein and Day, 1979, 28, 36, 41, 50-54, 79-80, 82-87, 107, 240.

- Larson, T.A. Wyoming’s War Years, 1941-1945. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming, 1954, 206, 218-220.

- Taylor, Paula Bauman. FE Warren Air Force Base. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2012, 7.

- Thompson, Antonio. Men in German Uniform: POWs in America during World War II. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2010, 1-3, 130.

- Wyoming Journal. “German Ex-soldier Visits POW Camp.” Aug. 28, 1975.

- Wyoming State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. “Camp Douglas Officers’ Club State Historic Site.” Undated pamphlet, Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum, Douglas, Wyoming.

Illustrations

- Camp Dubois commander Harold Harlamert’s photos of the large group of POWs, the three German cooks with their Christmas cakes and of the enlisted men with their trout are courtesy of Linda Siemens. Used with permission and thanks.

- The map of POW camps is by the author, used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of the two POWs in a beet field and of the Camp Wheatland tents are from the Laramie Peak Museum, Wheatland, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Camp Douglas fencing is from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of the murals in the Camp Douglas officers’ club and of the wooden tank are from the Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Blessed Mother plaque made by an Italian POW of plaster of paris was taken by Marian Testolin Offe. Used with her permission, with thanks.