- Home

- Encyclopedia

- An Italian Painter In a Wyoming POW Camp

An Italian Painter in a Wyoming POW Camp

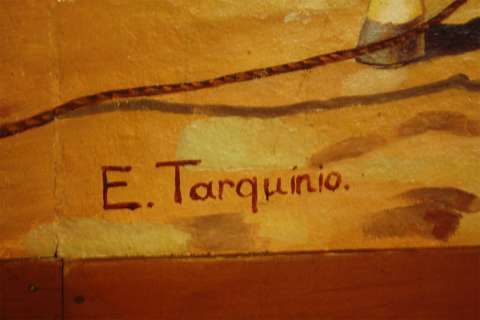

Three initials, three mysteries: L. DeRossi, V. Finotti, E. Tarquinio. These are the three signatures on 10 panels out of 17 murals at the former officers’ club of the World War II prisoner of war camp in Douglas, Wyo. Very little is known about the murals and until now the identities of the artists have never been uncovered.

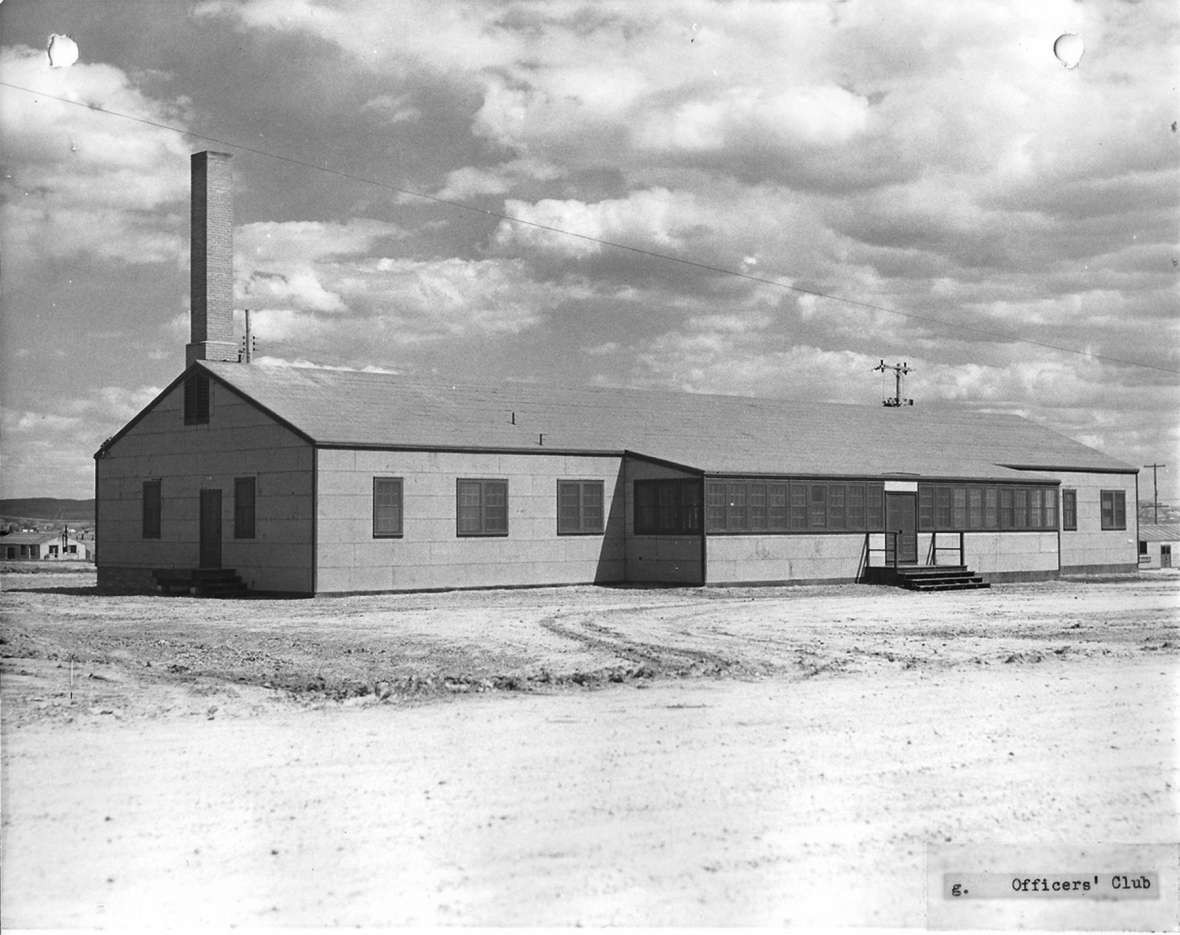

The club was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001. Today the Camp Douglas Officers’ Club State Historic Site is under the care of the nearby Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum in Douglas, which also holds a collection of artifacts from the camp.

Among the material in the museum’s archive are two small paintings, one seemingly of Venice, signed “Enzo Tarquinio, 1943, S.U.A” (S.U.A., the Italian acronym for U.S.A., Stati Uniti d’America), the other of Saint Rita of Cascia, signed “Italy.Enzo.Tarquinio.1943.” And there it is: a full name, Enzo Tarquinio.

With a first and last name I was able to locate members of the Tarquinio family in Italy, including Enzo Tarquinio’s younger brother, Sergio Tarquinio, and a nephew, Marco Tarquinio. On Sept. 21 and 29, 2020, I spoke by telephone with 95-year-old Sergio. His words, with my translations, are quoted throughout this essay. Along with the aid of other research, I have pieced together a brief history of one of the muralists at Camp Douglas.

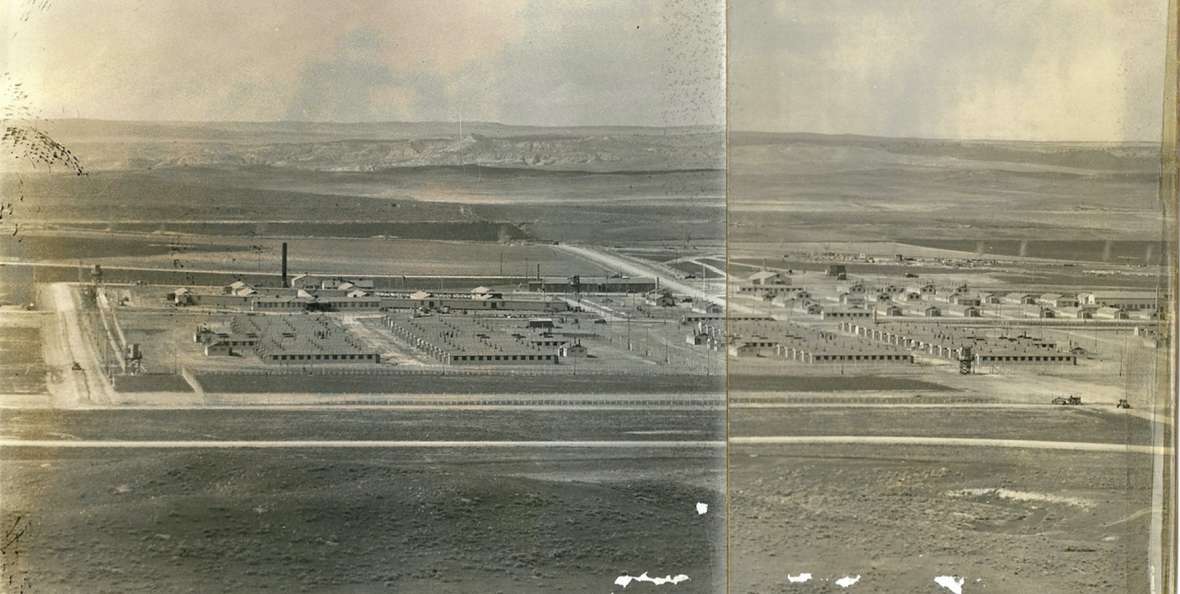

During World War II, Wyoming housed German and Italian prisoners of war (POWs) in two main base camps, Camp Douglas and Fort Francis E. Warren, as well as over a dozen branch camps where men were sent to work. Camp Douglas, about a mile square, was built just east of the town of Douglas in late spring of 1943 and received its first POWs in August of that year. The camp could house at least 3,000 prisoners and 500 U.S. army personnel; at different times nearly 2,000 Italians and 3,000 Germans were detained. The Italians were gone by late spring 1944; Germans began arriving that summer, after the Allied invasion of Normandy. By early 1946 all remaining POWs were repatriated and the camp closed. While no Japanese POWs were detained in Wyoming, the state did hold as many as 10,000 Japanese Americans at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center between Cody and Powell, Wyo., through the duration of the war.

Early years

Understanding the life history of one of the Camp Douglas POW-muralists helps us make sense of how the officers’ club decorative murals came to exist and gives deeper meaning to the preservation and restoration work that has been and continues to be done in Douglas. Enzo’s story also illustrates how events and experiences that seem so far away have impacted the Cowboy State, reminding us of how local histories are so often tied up with larger, global events.

Enzo Tarquinio (b. May 21, 1911- d. Oct 20, 1985) was from Cremona, a northern city in the Italian region of Lombardy most famous for being the birthplace of the Stradivarius violin. He was raised in a large family—five sisters and one brother. His father, Tito Tarquinio, also from Cremona, had a small business and loved to paint when he could; his mother, Giovanna Orlando, was originally from Spilimbergo (Pordenone province), in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region. The couple met in 1896 and settled in Cremona, where Enzo was born.

When Enzo was 8 years old, in 1919, Benito Mussolini organized the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento. His para-military group, made up of Squadristi (Blackshirts), began to incite riots and urban violence, eventually leading to Mussolini’s famous March on Rome in 1922 and soon after the overwhelming control of the Italian government and the beginning of his twenty-year reign as the Fascist dictator of Italy. Italy would enter World War II as part of the Axis Powers, but it would end the war on the side of the British and the United States, the Allies.

No one in the Tarquinio family ever became members of the Fascist Party—“nessuno in casa nostra era Fascista” (‘no one in our house was a Fascist’) clarified Sergio— but both Enzo and his brother, Sergio (14 years his junior), were eventually drafted into the Fascist military and served in World War II. The lives of men who were forced to fight for a cause they had not voluntarily embraced is one of the many complexities of this story.

A young artist

From a young age Enzo was already an aspiring artist:

mio fratello dall’eta di 11-12 anni aveva questa grande passione e iniziò a lavorare in una cooperativa di pittori a 15 anni ... fino a 22 anni … e poi si mise da solo e lavorò sempre da solo finché fu chiamato alle armi.

from 11-12 years old my brother was very passionate [about art] and when he was 15 he began to work with a cooperative of painters… until age 22 … then he went to work on his own and he always worked on his own until he was drafted into the military.

Before the war Enzo also studied fine arts for four years in Cremona, learning decorative painting as well as art restoration. He was particularly well-schooled in the history of the Italian Renaissance; his life-long passion, Sergio told me.

Enzo’s love of art rubbed off on his younger brother, and Sergio recalled to me with fondness watching his older brother paint and draw. Sergio, in fact, also became an artist and worked at times with his brother, painting murals on walls and wood doors in private houses—he recalls in particular a large house where they painted multiple pieces in the style of Rococo painter Giambattista Tiepolo.

Interestingly, Sergio became a much better-known artist than his older brother. Today he is counted among the most accomplished Italian cartoonists of the 20th century, especially, but not only for his work on popular comic book series that are part of an influential Italian Western-themed comic genre. That Enzo’s brother Sergio would be known for his popular illustrations of the myth of the American West is yet another of the curiosities of this story.

The capture

When Enzo was called to the military, his artistic background made him a good fit for the job of “osservatore” (‘artillery or forward observer’). As Sergio explains “fu scelto per fare disegni di postazione” (‘he was chosen to draw images of positioning’). Sergio went on to describe how Enzo’s experiences painting on the walls and ceilings of churches and older buildings meant he had a good eye for perspective and distance, skills that came in handy for the sketches he had to do on the front line.

During the war Enzo first spent two years on the Russian front, where he nearly missed being killed and instead was “ferito leggermente” (‘barely wounded’) and sent back to Italy to recover. Once recovered he was deployed again, this time to Sicily, where the Allies were about to invade as part of Operation Husky. And it was there on July 10, 1943, that Enzo and others in his battalion were captured by American Rangers. Sergio says that his brother used to recount the moment of his capture like this:

un tenente Americano gli chiese, ‘Surrender?!’ e lui, che sapeva qualche parole di inglese gli disse, ‘Yes, I will!’.

an American lieutenant said to him, ‘Surrender?!’ and since he knew a few words of English he said to him, ‘Yes, I will!’.

Soon after the prisoners were placed on a Liberty ship (a U.S. mass-produced wartime cargo ship) and brought to Morocco. He spent about 10 weeks in an American POW camp in Morocco and then he sailed on another Liberty ship to the United States, landing in the harbor at Wilmington, N.C. From there he and others were put on American passenger trains and embarked on a four-day trip to Douglas.

Camp Douglas

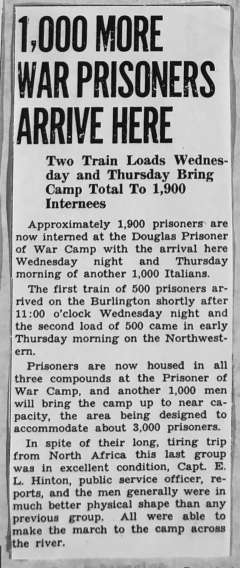

Local newspaper sources tell us that Italian POWs arrived at Camp Douglas on at least three occasions in 1943: Aug. 13th, Sept. 9th and Sept. 29th or 30th.. These dates correspond almost exactly with Sergio’s memory of the dates of his brother’s journeys taken nearly 70 years ago and place Enzo’s arrival in Wyoming on Sept. 29 or 30, 1943.

The chronology of Italy’s involvement in the global conflict is important to keep track of as we attempt to shape Enzo’s involvement in the mural paintings. By the time of his arrival in Wyoming, a lot would have changed for Italy. On Sept. 3, 1943, the Italian General Pietro Badoglio had signed the Cassibile Armistice with the Allied Forces, an event that was announced on Sept. 8, 1943. And in Douglas the news of Italy’s surrender and new relationship with the Allies was noted in The Douglas Budget on Sept. 16th.

Among the details of the armistice was the status of prisoners of war: All Allied POWs had to be released but it did not clarify what happened to Italian POWs. As a result, confusion remained around the Allied-held Italian prisoners. By December 1943 General Badoglio called for Italian POWs to collaborate with their new ally, the United States. By early 1944 the United States came up with a plan: Italian POWs could be asked to renounce Fascism and volunteer for noncombatant service, although they would remain under the restricted custody of the Allies until the war ended. The first such noncombatant Italian Service Units of collaborating Italians were formed in the United States in March 1944. By then, we know the murals at the Officers’ Club at Camp Douglas had already been started and maybe even completed (two panels are dated “Dec 43,” two “1944” and one “1943;” the other 12 are not dated).

Once the POWs arrived in Douglas they were screened to determine what kinds of skills or trades they might have. POWs took care of much of the daily running of the camp and, starting in October 1943, many also worked outside the camp on farms and ranches.

The murals

Given his background in art, Enzo Tarquinio (and others) were asked to paint murals on the walls of the American officers’ club in the camp: “a mio fratello fu chiesto di dipingere sui muri del club dei capi americani scene che rappresentassero la colonizzazione degli Usa” (‘my brother was asked to paint on the walls of the American officers’ club scenes that represented the colonization of the USA’).

Sergio explained that Enzo and the other artists chose the time period of the 19th century, ending with the “ultimo massacro degli indiani nel 1890” (‘last massacre of the Indians in 1890’), an event I assume refers to Wounded Knee. We can only wonder today if the American officers at Douglas knew about the Western-themed murals being painted by American soldiers, starting in October 1943, some fifty miles away at the servicemen’s club at the Casper Army Air Base.

Looking at the oil-painted murals at Camp Douglas today, we can see aspects of the story of colonial settlement, or at least a somewhat iconic version of it (covered wagons, a saloon brawl, a cattle round-up, a bison skull) as well as identifiable landscapes (Independence Rock, natural geysers). The artists depicted no violence against American Indians, who are represented in primitive imagery, standard for the time: a stoic figure against a mountain, two men sharing a peace pipe. The murals show no families and no women.

As others have already documented, the murals’ Western-themed images were mostly borrowed or otherwise heavily influenced by some of the work of early 20th century artists of the U.S. West, especially Charles Russell and William Henry Jackson. The practice of artistic copying was not uncommon among Italian artists.

Were the Italians shown illustrations or books of Western art? Did they find such illustrations in magazines or newspapers donated by the local Red Cross? Were they specifically asked to paint a particular set of images? So many questions remain. Yet Sergio Tarquinio’s account helps us imagine why they might have chosen these particular images to paint, and even why they took to painting the murals at all.

For Sergio, who, until we spoke, had never seen photographs of the murals and did not know the building had been preserved, the reason is clear. His brother, who he described as “abbastanza timido” (‘rather timid’), had quickly developed a good rapport with the Americans who respected his creativity. Enzo and the other artists at Camp Douglas often painted or drew other subjects, including portraits of the U.S. soldiers on guard as well as the civilian women who worked in the camp. Today we have some examples of these works because the Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum has preserved them.

Sergio recalls that his brother talked about a Col. Charles Wingate (spelling uncertain) who was “molto affabile, molto gentile ... mio fratello diceva sempre cosí di lui” (‘very easy going, very kind…my brother always spoke of him like that’). Sergio recounts that this colonel—who is not on record as having served at the camp--gave Enzo a gold ring with an insignia on it when he left Camp Douglas and, he added with some emotion in his voice, “lo abbracciò, lo abbracciò” (‘he embraced him, he embraced him’), he repeated, making sure I understood the importance of this simple act of friendship and care.

Enzo was later transferred to an Italian Service Unit at Camp Belle Mead, N.J. After the war he was repatriated to Italy and began working again as an artist, doing decorative and restoration work as well as occasional graphic design. (Sergio noted the chocolate company Perugina as a one-time client.) He never returned to the United States and yet “con molto affetto ricordava il suo tempo negli Usa” (‘he affectionately remembered his time in the USA’).

In 1985 at the age of 74 Enzo was restoring a fresco in a small church about 20 kilometers from Cremona when he fell ill. He went home quickly and died 20 minutes later, having suffered a heart attack. Today a bust of Enzo Tarquinio stands along others in the “Viale degli artisti” (the street of the artists) near the Tarquinio family tomb in the Monumental Cemetery of Cremona, Italy.

(Research for this project was generously funded by the Lola Homsher Endowment Fund and a Mellon/ACLS Community College Faculty Fellowship.)

Resources

Primary Sources

- Camp Douglas Files. Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum, Douglas, Wyo.

- Douglas P.O.W. Camp Interview Collection. Interviewer Mark Junge, 2012. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- Tarquinio, Sergio (Cremona, Italy). Telephone interviews with the author, Sept. 21 and 29, 2020.

Secondary Sources

- Doyle, Robert C. The Enemy in Our Hands: America’s Treatment of Prisoners of War from the Revolution to the War on Terror. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 2011, 179-201.

- Keefer, Louis. Italian Prisoners of War in America, 1942-1946: Captives or Allies? New York: Praeger Publishing, 1992.

- Larson, T.A. Wyoming’s War Years: 1941-1945. Laramie, Wyo.: University of Wyoming Press, 1954, 217-221.

- Noyes, Dorothy. “The Satisfactions of Reproduction: A Baroque Painter in Italian Philadelphia.” Folklife Annual 1990. Washington: Library of Congress, 1991, 58-69.

- O’Brien, Cheryl. World War II POW Camps of Wyoming. Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2019.

Illustrations

- The images of Enzo Tarquinio’s paintings of Venice and St. Rita of Cascia, the two newspaper images, the photo of the officers’ club and the photo of Camp Douglas from the air are all from the collections of the Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum in Douglas, Wyo. Used with permission and thanks.

- The portrait of Enzo is courtesy of his brother, Sergio Tarquinio. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the corral scene mural is by the author. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Independence Rock mural is by Tom Rea.