- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Wyoming Lawyer Melville C. Brown: A Man For His...

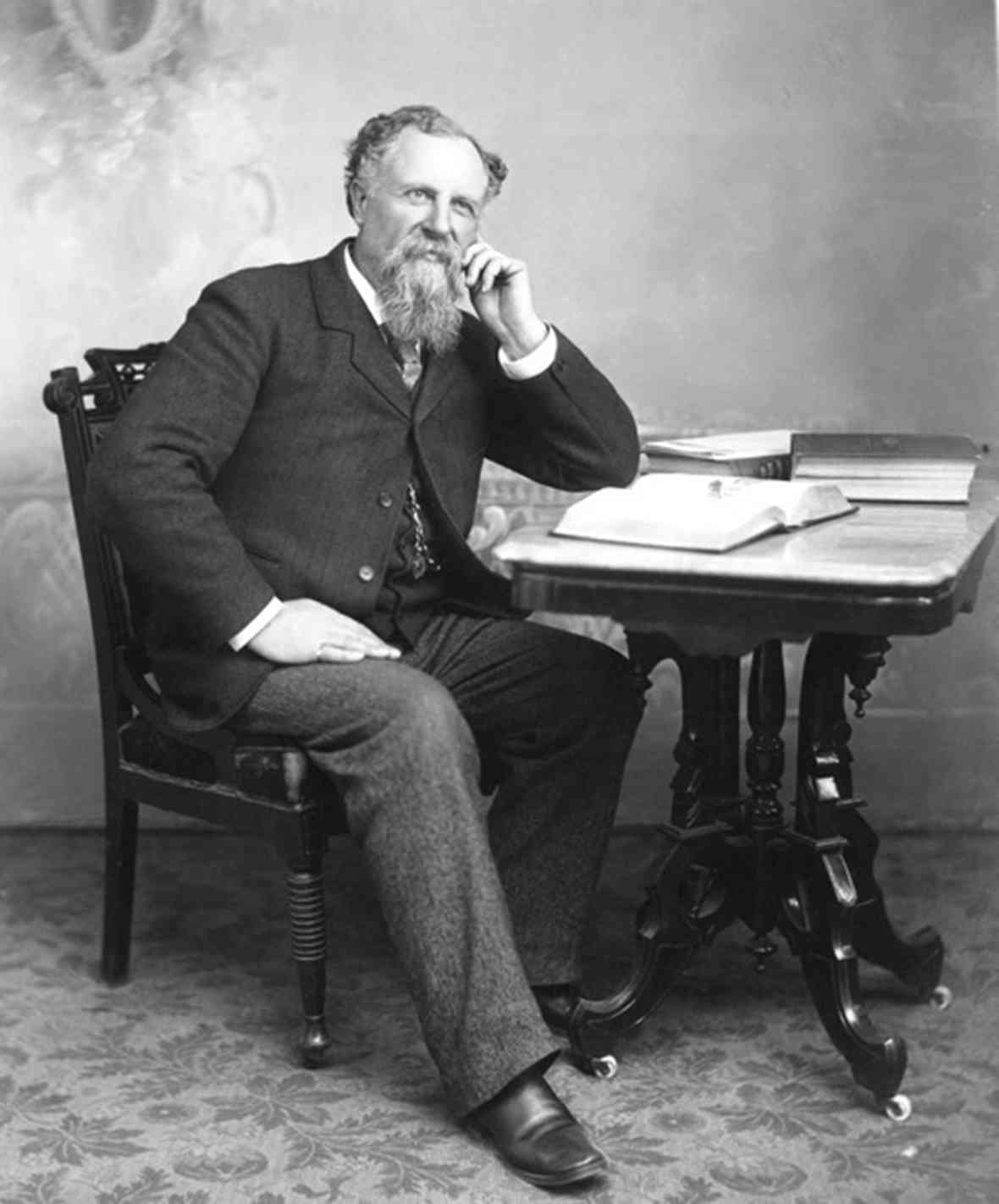

Wyoming Lawyer Melville C. Brown: A Man for his Time

M.C. Brown’s legal career spanned 60 years and thousands of cases during the years Wyoming was moving from territory through early statehood. President William McKinley’s appointment of Brown to a federal judgeship in Alaska in 1900 proved disastrous for the attorney, however, who returned to Wyoming where he continued to practice law, but on a much smaller scale.

Brown’s cases engaged some of the most significant legal issues of his time in the West. He challenged the right of a woman to sit on a jury; he opposed the illegal fencing of federal land; he helped defend the invaders of Johnson County after the so-called Johnson County War; and, before the U.S. Supreme Court, he successfully challenged longstanding estate law that protected a widow’s right of dower.

Brown’s early years

Melville Cox Brown was born near Vassalboro, Maine, most likely in 1835, though the exact year is not clear. By 1853, M.C. Brown, as he was most often called, left his home and traveled via ship and the Isthmus of Panama to the California gold fields. In 1862, he moved on to Idaho Territory, where he was engaged in mining and served as the assistant U.S. Assessor for the territory. After serving in the Idaho Territorial Assembly as a Republican representing Boise County, he departed for Cheyenne, Dakota Territory, in late 1867. In three autobiographical documents—two of which History of Albany County and Early Lawyers and Early Courts are now held at the Wyoming State Archives and a third, untitled, written for John D. Hicks of Hamline University in St. Paul, Minn.—Brown does not detail why he left.

Upon arrival in Cheyenne, then still in Dakota Territory, Brown entered the legal profession when he was admitted to the Dakota Territory bar in the early spring of 1868. He was examined by District Judge Asa Bartlett and, based on knowledge he had gained reading law in the offices of Judge Milton Kelly in Boise, started his legal career.

Brown moved to Laramie City in May 1868, and began what would become a 60-year long residence. He immediately opened a legal practice and soon married Nancy Fillmore, the daughter of prominent Laramie resident and Union Pacific Railroad executive Luther Fillmore. The couple had three daughters, Adelaide, Ethel and Susan. Brown’s legal acumen led to a number of prominent cases, including two of national importance, and soon was providing a handsome income.

Significant legal cases

Brown’s own accounts of his cases in History of Albany County and Early Lawyers and Early Courts listed only four out of the thousands he tried. The first was a jury trial in Laramie in March 1870. In the trial he challenged the right of a female juror to serve. By his own later admission, he was at the time opposed to female suffrage and that likely influenced his attempt to keep her out of the jury box. (Brown does not name the woman in his account, and unfortunately the trial record is missing from the State Archives.) However, Brown soon changed his opinion and while serving as a stalwart Republican in the 1871 Wyoming Territorial Assembly, voted to block the Democrats’ attempt to remove women’s right to vote.

His Republican connections were also largely responsible for his selection as superintendent of construction of the territorial penitentiary, his election as Albany County prosecutor and his appointment in 1880 to a four-year term as U.S. attorney for Wyoming Territory. In the latter role he was the first United States official to challenge large cattle interests that were illegally fencing public lands.

Small cattle operators had complained to the Department of the Interior that illegal fences were preventing their access to public lands to graze their cattle, thus limiting their income. Beginning in 1883, Brown was directed by the Department to remedy the situation. He chose, as U.S. Attorney, to issue injunctions against the operators requiring them to remove the fences. The first injunction was issued against the Swan Cattle Company, one of the largest operations in the Territory at the time. He was successful in this effort, the second of the four major cases he later recounted as highlights of his career.

This did not mean, however, that his efforts were always directed against large and powerful interests. In the third case he listed, he was one of the members of the winning defense team that managed to get charges dropped against the invaders of the 1892 Johnson County War. That team was led by Willis Van Devanter, a stalwart Republican who would go on to be a United States Supreme Court Justice.

The final case Brown described his latter accounts concerned the way in which a widow’s portion of her husband’s estate was treated in the face of financial claims. In a case in Carbon County, Brown represented his brother, William Brown and another man, John Connor, in their claim against a the estate of James France for debts owed them. Up to that point, existing law guaranteed a widow at least one-third of her husband’s estate upon his death. While she was alive, the old concept held, she could not be compelled to use those protected assets to settle outstanding claims against her late husband's estate. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown’s favor, and France had to pay the claim by Connor and William Brown.

In his long career, however, M.C. Brown defended anyone who needed legal assistance. In keeping with his legal philosophy, he did not limit himself to high profile cases. Be they murderers, thieves, prostitutes or cattle barons, he represented them with equal vigor, teaming at various times with such prominent attorneys as C.P. Arnold, J.P. Brockway and John Blake.

Brown’s political contributions

Decades apart, Brown served two terms as mayor of Laramie. He was the city’s first mayor in 1868, serving for only a short six weeks. He served a full term at the end of the century.

In 1889 his legal prowess and Republican backing suited him well as a delegate to, and president of, the Wyoming Constitutional Convention. Brown was most prominent in the deliberations for his support of language ensuring that all water sources in the state be put to their best use. He was also a vocal supporter of the new constitution’s guarantee of the right of women to vote. His efforts to tax coal as a source of government revenue, however, failed. They were doomed by arguments that such a tax singled out the Union Pacific Railroad—the railroad at the time controlled nearly all the coal mined in Wyoming—and that the influx of funds would lead to a bloated government.

Failed business ventures

Despite his legal talents, Brown rarely succeeded in business. In 1872, he tried unsuccessfully to fund construction of a railroad from Denver to Laramie and on to Iron Mountain northwest of Cheyenne, location of a supposedly rich deposit of iron ore. Over the next three decades he likewise failed at mining ventures in North Park, Colo., and at the mining camps of Keystone, then in Carbon County, and Cummins City in Albany County, Wyoming. He also failed in attempts to speculate in real estate on the outskirts of Laramie.

His greatest debacle, however, was his investment in purebred draft horses imported from France. In a confessional letter to his friend John Meldrum, who served as secretary of Wyoming Territory and later as the first commissioner of Yellowstone National Park, Brown claimed that he lost $50,000 in the venture.

Disastrous Alaskan appointment

Brown’s legal career reached its pinnacle in 1900 when President William McKinley appointed him judge for the U.S. District of Alaska.

The posting, however, did not end well. Brown’s hopes for another four-year term were derailed by an investigation into claims that he made financially self-serving rulings from the bench.

The claims were seldom specific and the names of his accusers were never made public. One specific claim involved his ruling in a case about a "light plant" in which he allegedly had an interest. Brown told the Seattle Post Times that the claim was false as he sold his interest before the matter came to court—and his ruling in the case was not appealed. There were other non-specific charges that he ruled in cases about mining claims in which his court, including his clerk, had an interest.

Brown refuted the charges in an interview with the Seattle newspapers in the fall of 1904, and sent a letter to the attorney general stating the charges were "silly." His refutations failed however, newspapers from coast to coast pilloried him and President Theodore Roosevelt declined to appoint him to a second term on the bench. Sadly for Brown, the broader public would never learn that the evidence did not support the charges.

After his term in Juneau concluded, Brown entered a law practice in Seattle, where he remained though 1907. He returned to Laramie in 1908, reopened his law practice there and served two terms as justice of the peace and police judge. The Alaska affair and his advanced age apparently reduced the demand for his services, and he was involved in only minor cases that produced little income. By 1923, he was no longer listed as an active attorney in city directories. Serious health issues plagued him in later years. He died of heart failure on April 9, 1928, in his Laramie home.

Despite his highly successful legal career, Brown never achieved the financial stature that he sought throughout his life. When he died, his estate was valued at only $2,500. He had lived in the same ramshackle house he bought in 1875, and his legacy soon faded into obscurity.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Brown, Melville C. “History of Albany County, Wyoming.” Manuscript 319, 1927. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- ______________. “Early Lawyers and Early Courts.” Manuscript no. 319A, N.d. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- ______________. Probate Record 1285. Petition of Nancy Brown for Letters of Administration before the State of Wyoming Second Judicial District. 28 April 1928. Wyoming State Archives, Cheyenne, Wyo.

- _____________. Letter to John W, Meldrum, Nov. 23, 1908. John W. Meldrum Papers, Collection 04338. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- Brown, Melville C. and John D. Hicks. “Autobiographical Sketch.” Manuscript Biographies Collections. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minn. 1917.

- Department of Justice Files, Record group 60, Applications and Endorsements, 1901-1933 file number 25013. National Archives, College Park, Md.

- France v Connor U.S. Supreme Court 161 U.S. 65. 2 March 1896.

- House Journal of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wyoming. Cheyenne, Wyoming: By Authority, 1872.

- Journal and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Wyoming: Begun at the City of Cheyenne on September 2, 1889. Cheyenne: Daily Sun, 1893.

- Laws, Memorials And Resolutions Of The Territory Of Dakota: Passed At The Fifth Session Of The Legislative Assembly, Concluded January 12th, A.D. 1866. Yankton, Dakota Territory: G.W. Kingsbury, 1866.

- National Endowment for the Humanities and Library of Congress. "National Digital Newspaper Program." The National Endowment for the Humanities, accessed May 28, 2015 at http://www.neh.gov/projects/ndnp.HTML. For his book on M.C. Brown (see citation, below), the author used this and other resources to consult more than 150 newspapers, mostly the Laramie Boomerang, the Laramie Sentinel, and the Cheyenne Leader, as well as the Boise Statesman, the Seattle Post Intelligencer, the New York Times, Alaska Daily Dispatch, Wyoming Tribune, Seattle Times, Juneau Daily Alaska Dispatch, Rawlins Republican, Cheyenne Sun, Cheyenne Tribune, Saratoga Sun, Owyhee, Idaho Avalanche and the San Francisco Call.

- Seattle Post Times. “Judge Denies Charges” July 28, 1904 p. 4

- Wyoming State Library. Wyoming Newspapers, accessed May 28, 2015 at http://www.wyonewspapers.org/. The Laramie Boomerang, the Laramie Sentinel, and the Cheyenne Leader, see above, were consulted via the Wyoming Newspaper Project.

Secondary Sources

- Frye, Elnora L. Atlas of Wyoming Outlaws at the Territorial Penitentiary. Laramie, Wyo.: Jelm Mountain Publishing, 1990.

- Hebard, Grace Raymond. “The First Woman Jury.” The Journal of American History 7, no. 4, (1913): 1293-1341.

- Hunt, William R. Distant Justice: Policing the Alaskan Frontier. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming, 2d ed., rev. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

- Naske, Claus. A History of the Alaska Federal District Court System, 1884-1959, and the Creation of the State Court System. Fairbanks, Alaska: University Of Alaska, 1985.

- Roberts, Phil. "The Wyoming Constitutional Convention and Adoption of Wyoming’s Constitution. Accessed Jan. 10, 2015, at http://www.uwyo.edu/robertshistory/wyoming_constitutional.htm.

- Viner, Kim. Melville C. Brown: Frontier Lawyer and Jurist. Laramie, Wyo.: Kim Viner, 2015.

- Wyoming State Bar Association, Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Meeting. Cheyenne, Wyo.: S.A. Bristol Co., 1919.

For further research

- The Laramie Plains Museum (see field trip suggestion, below) includes among its collections M.C. Brown’s Victrola, as well as the bedroom furniture he and his wife, Nancy Fillmore Brown, brought back to Laramie from their time in Alaska. For many years, the museum misidentified two full-length portraits in its collection as showing M.C. Brown and Nancy Brown. After much investigation, however, the paintings turned out to be portraits of John Sherwood and his daughter, Mary Sherwood, who gave $200,000 about 1925 to the Episcopal Diocese of Wyoming to build a boys’ boarding school in Laramie. The building is now called Hunter Hall and used as office space for St. Mathew’s Episcopal Cathedral. The paintings were mis-labeled on the rear of the canvases.

Illustrations

- The A.J. Russell photo of the Union Pacific Railroad tracks, roundhouse and machine shops in Laramie about 1868 is from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Denver Library Photographic Collection. Used with thanks.

- The portrait of M.C. Brown is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Albany County Courthouse is from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.