- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Lawyers and The Law In Early Wyoming

Lawyers and the Law in Early Wyoming

When, at 2 p.m. on July 9, 1867, James Whitehead pitched his tent in the middle of an empty plain next to Crow Creek, he became not only Cheyenne’s first resident but its first lawyer. Three hours later, according to Saltiel and Barnett's History and Business Directory of Cheyenne (published barely six months after the town was founded), two individuals and three families pitched tents around Whitehead's and the "Magic City" sprang into existence.

The next day, a second lawyer, W. W. Corlett, stopped at Whitehead's tent. By that afternoon, the two had formed a partnership with Corlett buying in with a $5 greenback. They put up their shingle and by the end of the month, they started construction of Cheyenne's first two-story building. Two weeks after that, they were joined by five or six more lawyers in town who helped organize local government. By the end of the year, nine lawyers advertised in the business directory, along with the justice of the peace, Melville C. Brown, who by April of the following year was serving as Laramie's first mayor.

That is not to say that the Cheyenne lawyers were the first in what is now Wyoming. Dozens, if not hundreds of lawyers accompanied the overland migrations to Oregon and California in the 1840s and 1850s. Historian John Phillip Reid quotes a Sacramento newspaper complaining that the city was "overrun with doctors and lawyers." While only a third of the million or so travelers to the West Coast in those two decades opted for the land route crossing Wyoming, it is likely that the same percentage of lawyers made that choice, too. In fact, many lawyers were counted among the wagon trains west, some of them responsible for drafting the rules under which the covered wagon travelers agreed to abide. There is no record of any of them permanently settling or even tarrying very long in what is now Wyoming.

But there is even earlier evidence that a lawyer's services were used in what’s now Wyoming. Mountain man and fort builder Jim Bridger and his business partner Louis Vasquez (the literate member of the partnership) must have hired a lawyer (almost certainly not local) to file what is likely the first property deed for land in Wyoming. Formal filing was made in Mexico City because, at the time (1843), the land on which Bridger and Vasquez built their fort was a part of Mexico.

Forming a territory

Before the territory of Wyoming was organized in May 1869, local ordinances provided the statutory law. Wider jurisdiction was variable, depending on the year. What is now Wyoming was part of the Oregon and Nebraska territories, with parts under the jurisdictions of Utah, Idaho, Washington, and Montana at various times.

When the transcontinental railroad started bringing significant populations, most of what is now Wyoming wound up as "Laramie County" under the jurisdiction of Dakota Territory. The county was a huge appendage, far west of Yankton, the territorial seat of government. To conduct any territorial business or to file legal papers, long trips to eastern Dakota would have consumed significant time for lawyers and their agents.

Reacting to complaints from that county's lawyers and politicians, and knowing the railroad would bring thousands of newcomers sharing little in common with their most numerous constituents, farmers of "east river" Dakota, the governor and legislature asked Congress to give the western portion to another territory or even make it self-governing.

Image

While it is unclear how rigorously the county was shopped around to neighbors, the U.S. Congress created and named the county as the separate territory of "Wyoming." President Andrew Johnson and Congress were locked in the struggle that would lead to Johnson's impeachment; the appointments of the President's choices to govern the new territory were kept in limbo. Wyoming was not organized as a territory, complete with territorial officials and courts, until President Grant took office in March 1868.

Ohio lawyer and former Civil War army officer John A. Campbell of Ohio, the first territorial governor, arrived in Wyoming by train, just weeks before the tracks met at Promontory Point, Utah. By the fall, the first territorial legislature convened, passing a lengthy list of laws that would be the framework for the new government. The most celebrated of those laws granted equal political rights to women, making the new territory the first government to recognize women's equality.

By the following year, women were voting and a woman, Esther Hobart Morris, was presiding over the Justice of the Peace court in the mining town of South Pass City—the first woman anywhere to be appointed to a judgeship. Soon after, women were serving on juries in Laramie, another first for women anywhere.

Lawyers in public service

Wyoming's earliest lawyers represented clients, but they branched out into a variety of other endeavors, most prominently in government service. The first five territorial governors, appointed by the president, were lawyers. Six of the eight territorial secretaries (equivalent to today's secretary of state) had studied law.

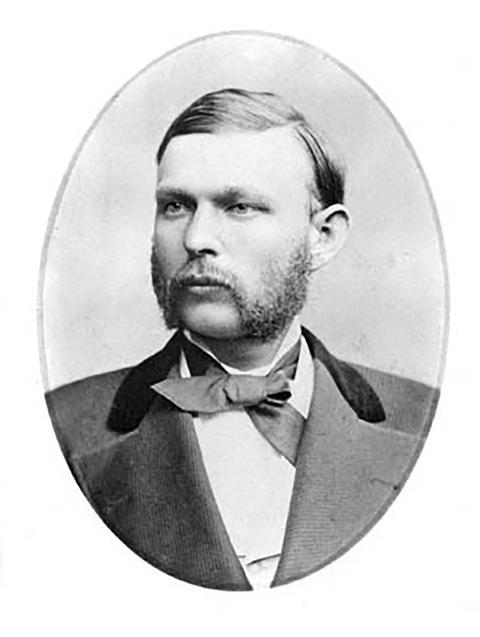

Seven men were elected by Wyoming’s voters to be delegate to the U.S. Congress during the territorial years. Five, including that pioneer attorney Corlett, were lawyers. Prior to coming to Wyoming, Corlett graduated from law school in Cleveland, Ohio, practiced law there, and taught courses in one of the few law schools in that state. A leader in the territorial bar, Corlett died suddenly in Cheyenne in 1890, just 12 days after Wyoming became a state. Delegate William T. Jones came from Indiana and after he lost his reelection bid as Wyoming delegate, he returned to Corydon, Indiana, where he practiced law until his death in 1882. William R. Steele, educated in the law in New York, served two terms as delegate to Congress and then relocated to Deadwood, South Dakota, where he served as mayor and practiced law until his death in 1901.

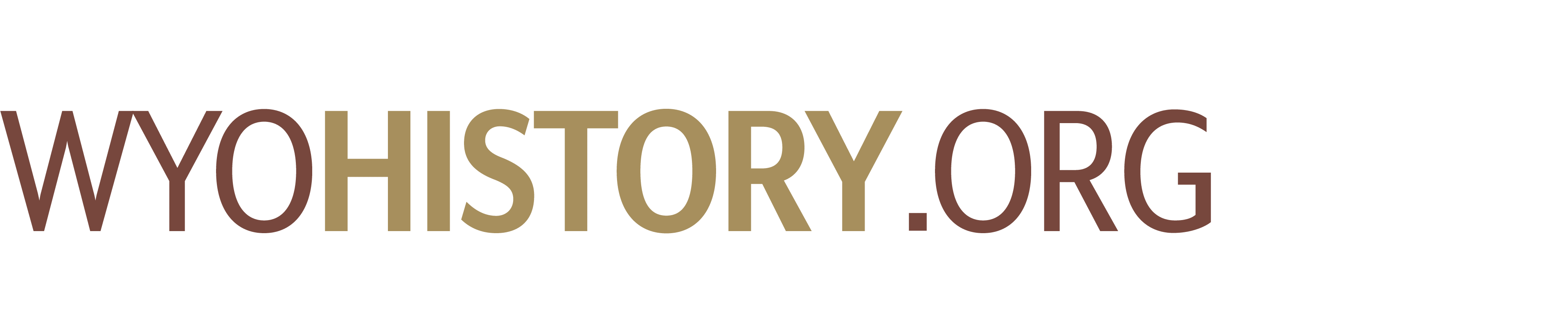

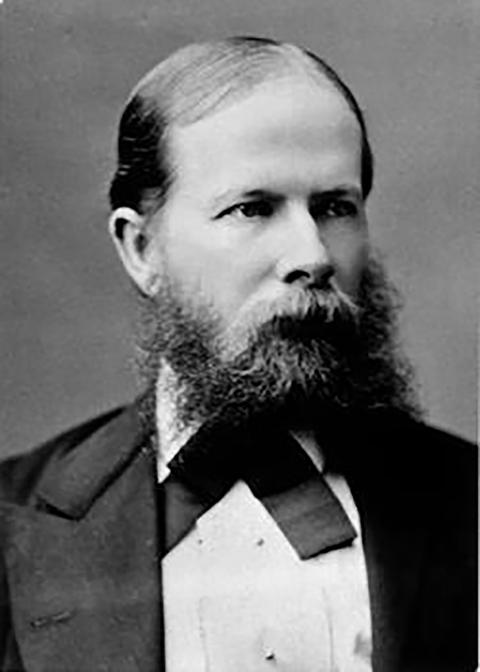

Stephen W. Downey, trained in the law in Washington, D.C., not only practiced law in Laramie before he was elected delegate to Congress, but also served as territorial auditor and treasurer. Sometimes known as the "founder of the University of Wyoming," Downey's name is the first listed on the register of lawyers, kept by the Albany County District Court clerk, of all lawyers appearing in court in the history of the county.

Image

The last territorial delegate, Joseph M. Carey, came to Wyoming as the first territorial attorney. Born in Delaware in 1845, he was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania law school. He was appointed territorial attorney at the age of 24 in 1869. President Grant named him to the territorial supreme court two years later. He was 26, probably the youngest person ever to serve on a supreme court of any state or territory. After Wyoming became a state, he was Wyoming's first U.S. senator and, later, governor of the state.

Most of the presidential appointees to territorial posts in Wyoming left the state soon after their terms expired. Campbell, the first territorial governor, went back to Washington, D.C., where he became an assistant secretary of state and, later, U.S. consul to Switzerland. John Thayer, the second territorial governor, returned to his law practice in Nebraska. Later, he was elected governor of that state.

Image

Dr. John Hoyt was territorial governor from 1878-1882. Hoyt practiced law and taught law courses in his native state of Ohio, but he also was trained in medicine. He was a practicing physician for a time and taught medical courses in Cincinnati. After he left the territorial governorship, Hoyt was one of the founders and the first president of the University of Wyoming. In that capacity, he not only served as president but taught courses in medicine, chemistry, ethics, principles of mining engineering and a full offering in law.

Even though it was not a requirement for appointment, all 16 men who served on the territorial supreme court were lawyers. Only five stayed in the territory after their appointments expired. A few of the 11 who left were picked by the president to serve on courts in other territories. Of those who stayed in Wyoming, three continued as State Supreme Court justices. The last chief justice of the Territorial Supreme Court, Willis Van Devanter, stayed on just briefly as the first state chief justice. Later, he served on the Supreme Court of the United States, the only justice ever appointed from Wyoming to the nation's highest court.

Image

Particularly during the territorial and early statehood years, lawyers moved from town to town in pursuit of the best opportunities. Relocation commonly coincided with population increases in other Wyoming towns or increasing competition among lawyers where they had been practicing.

Lawyers’ lives

Creation of new counties and, therefore, new county-seat towns was an important incentive to relocate. The new counties always required legal talent both to represent government and to provide counsel for anyone else needing counsel in filing papers in courthouses or pursuing lawsuits or defense in trials.

Retainers from (or employment by) railroads were the most lucrative opportunities in the territory. John F. Lacey, who served briefly on the territorial supreme court, secured the Union Pacific's retainer for Wyoming.

Lawyers drafted livestock sale contracts and represented big open-range cattle companies. Like the clients they represented, they were subject to the vagaries of livestock prices and range conditions. Few small ranchers or Main Street merchants could afford keeping counsel on formal retainer, but out-of-state insurance and real estate firms hired local counsel. So did banks—and lawyers often served on their boards.

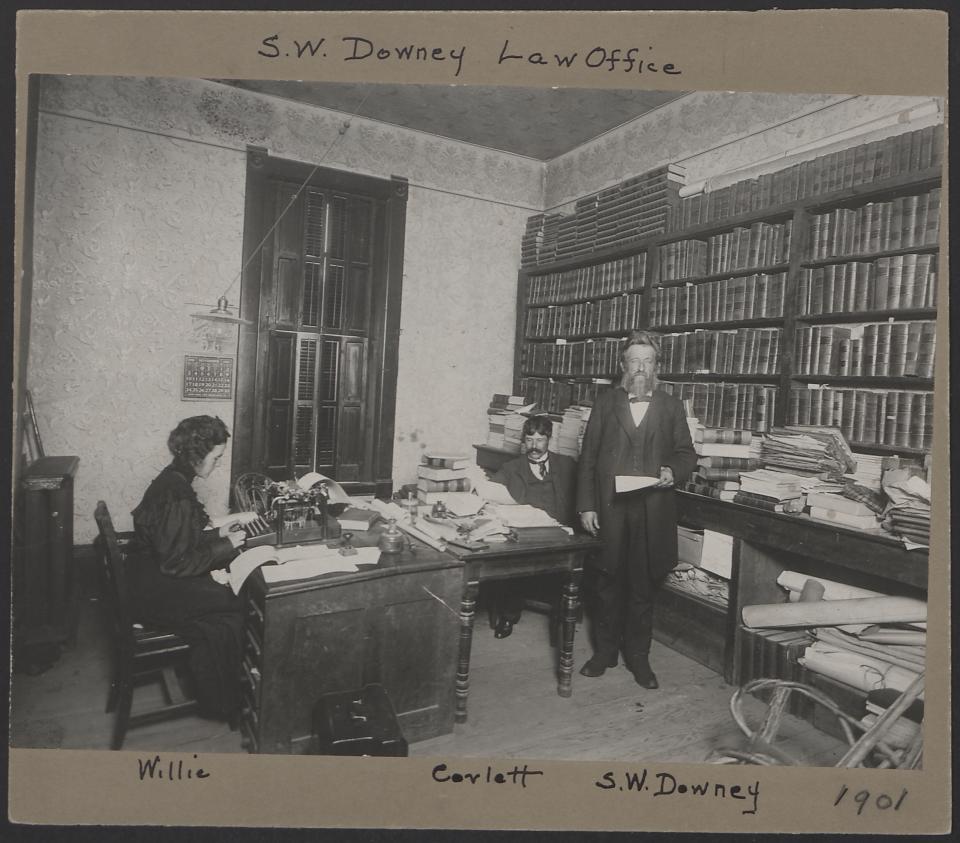

Because of the peripatetic lives of most lawyers in pre-statehood years, it is difficult to know how many people practiced law in the territory at any given time. Long before the State Bar was organized (Jan. 28, 1915) and before formalized legal education in Wyoming (the University of Wyoming College of Law opened in September 1920), the only sources for lawyer names and locations come from the extant court filings and the often casual "admission to practice" listings. These were made by the Territorial Supreme Court justices, who also served as trial court judges riding circuit throughout the year.

Except for the appointed territorial court judges, few lawyers were college trained. Most read the law in offices of more senior lawyers, gaining the knowledge much as a clerk. Qualities required for bar admission were largely up to the presiding judge who used his own methods to determine character and fitness. Written examinations were not formally specified until the end of the 19th century.

Local newspapers provide some indications of the legal activity in a community, not always through the news pages, but from the numerous display ads taken out by lawyers. Many such ads appeared on the front page, often in long two-column blocks along with ads for saddlemakers and mercantile stores. Some called attention to the lawyer's expertise in land law issues—sales, purchases and mining claims, for example. Game and fish violations were enforced early in the territory's history. Yellowstone National Park and other federal government reservations caused conflicts between Wyomingites and federal land managers. Disputes over water often ended up in court, sometimes because of fights and assaults stemming from them!

At various times during Wyoming’s 21 years as a territory, land offices opened in some towns, many presided over by lawyers appointed by the U.S. president. Property claims were a common part of most law practitioners' work. A number used their knowledge to expand into real estate development and speculation. Individuals trained in the law such as George Beck (a partner in William F. Cody's Shoshone Irrigation Company) and W. S. Collins, a founder of Basin, were town promoters.

Law and order

When it came to criminal law, Wyoming towns experienced fewer incidents of vigilantism and the few that did occur were far shorter than in most Western states. Respect for the rule of law, brought to the territory by its first residents and augmented by lawyers who were among the first arrivals, discouraged official corruption. It never was a serious problem in territorial Wyoming.

Effectiveness of law and order came into question with several notorious incidents in the 19th century. The infamous Rock Springs Massacre and the Pattee lottery scheme—when a grifter used a mailbox in the Laramie Post Office to sell tickets and swindle customers nationwide—hurt the territory's reputation. Numerous cases had to be brought in Wyoming for illegal fencing of public lands and fraudulent homestead claims. Treaty conflicts with Native people required often specialized legal expertise.

At various times in Wyoming history, the power of the railroads and of the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association caused concerns over the rule of law. The summer 1889 lynching of Ella Watson ("Cattle Kate") and James Averell led to arrests of a half dozen prominent cattlemen at the same time delegates were being elected to the state Constitutional Convention. The cattlemen escaped conviction; in Cheyenne, the 49 delegates, 11 of them lawyers, drafted the Constitution in 25 days.

One of the most serious violations in the state's early history was the invasion of Johnson County by a gang of wealthy ranchers and their hired gunmen. The "invaders" were captured, but escaped prosecution when Johnson County was unable to bear the cost of holding them in custody far away in Cheyenne.

Nonetheless, population growth and mineral exploitation brought even more business for lawyers. Most 19th century towns started as railroad stops and many were laid out by railroad surveyors. All tried to encourage settlement and it did not pay to have stories circulating nationally about outlaws, lynchings and gun violence in their communities. Many of the first newspapers were owned or edited by lawyers, most conducting their practices concurrent with their press connections. Promoting Wyoming places as law-abiding communities paid dividends through increased growth and economic prosperity.

Leadership from lawyers often led to town ordinances designed to discourage violence. The first mayors of many Wyoming towns had training in the law, even if they were not practicing lawyers. Each town had a city attorney to represent the town's interests and advise on the legalities of proposed ordinances.

Counties, courthouses

As the original five counties (Laramie, Albany, Carbon, Sweetwater, Uinta) were divided into the eventual 23 existing today, towns vied for county-seat status. Courthouses were important draws for settlers of all types who needed to pay taxes, serve on juries, or be parties to suits over land boundaries, contract breaches or domestic issues.

The courthouse brought potential customers to stores operating in the town and clients to lawyers normally congregated in offices close to the courthouse. Associated businesses grew up nearby and profited from countywide tax dollars spent to maintain courts, county jails and county offices. It is little wonder that competition for county seat status was often so bitter.

Lawyers served also in the state legislature, on school boards, on state boards and commissions, and as dependable donors and volunteers with non-profits in their communities. Throughout the territorial period, lawyers maintained the stability of many places by ethical representation of clients and by rendering public service to their towns, counties and the state. Today's Wyoming lawyers have a rich legacy of advocacy, ethics and respect for the rule of law, championed by those few hundred practitioners in 19th century Wyoming.

[Editors’ note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, support from which in part made publication of this article possible. Thanks also to the editors of Wyoming Lawyer, where an earlier version of this article appeared in April 2018. And special thanks to the author for making it available to us. Roberts holds the J.D. in law from the University of Wyoming College of Law and the Ph.D. in history from the University of Washington, Seattle. He was a member of the Wyoming State Bar from 1977 until his retirement in 2021. He taught legal, environmental and Wyoming/Western history at the University of Wyoming from 1990 to 2018.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Saltiel, E.H. and George Barnett. History and Business Directory of Cheyenne and Guide to the Mining Regions of the Rocky Mountains. Cheyenne, Dakota Territory: L. B. Joseph, Bookseller and Publisher, February 1868.

- Cheyenne Daily Leader, May 25, 1894.

Secondary Sources

- Davis, John. Wyoming Range War: The Infamous Invasion of Johnson County. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010. This is the best legal treatment of the subject.

- Erwin, Marie. Wyoming Historical Blue Book, 1946, 112-124 (Fort Laramie was the county seat of Cheyenne County, Nebraska. See maps showing what parts of Wyoming had been included in surrounding territories).

- __________. Wyoming Historical Blue Book, 1946. Biographical information of the governors, secretaries and judges comes from the brief biographies in this reference work.

- __________. Also see p. 1311.

- Keiter, Robert B. The Wyoming State Constitution. 2d ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. (A good overview of the constitution and history of its various components). Robert B. Keiter, The Wyoming State Constitution. 2d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Reid, John Phillip. Law for the Elephant: Property and Social Behavior on the Overland Trail. San Marino, California: Huntington Library, 1997, 17.

- Viner, Kim. West to Wyoming: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Stephen Wheeler Downey. Laramie, Wyoming: Self-published.

Illustrations

- The photo of the members of the Albany County Bar, and the image of the signature page listing early Laramie lawers are from the Albany County District Court, via the collections of the Laramie Plains Museum, with special thanks to Kim Viner of the museum. Viner, author of a biography of Downey, informs us that Stephen Downey was a close friend of W.W. Corlett, who with James Whitehead had formed Cheyenne’s first law partnership. W.W. Corlett and Downey had served together in the Union Army—both were captured at the battle of Harper’s Ferry in 1862. Stephen Downey appears to have named his son, Stephen Corlett Downey, for his good friend.

- The photos of John Campbell, John Hoyt and a young Joseph Carey are all from Wikpedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Stephen Downey in his law office with his son, Corlett, and his daughter, Willie, is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of Cheyenne in 1867 and of Willis Van Devanter are from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.