- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Taxing Wyoming Minerals: Severance Taxes and Pe...

Taxing Wyoming Minerals: Severance Taxes and Permanent Funds

When Democrat Ernest Wilkerson ran for governor in 1966, the Casper lawyer and auto parts store owner brought back the idea of levying a severance tax in order to bank Wyoming’s mineral wealth for the future. The concept had been considered at Wyoming’s constitutional convention in 1889, and again when a constitutional amendment was unsuccessfully proposed in 1924, but only sporadically in the years following.

Nearly 80 years after the constitutional convention, the proponents of a severance tax finally built enough support to enact one. A Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund (PWMTF) was created soon afterward to hold a percentage of severance tax revenues inviolate. The remaining severance tax revenues, plus interest generated by the PWMTF, now contribute funding to a broad spectrum of state services.

Debate begins at the constitutional convention

Most states rely on three taxes to fund their operations: sales taxes, property taxes and income taxes. Wyoming is among the seven states that do not levy an income tax. Instead, it derives revenues from its rich trove of mineral and energy resources by levying severance taxes.

How was this tax structure created? The story begins at Wyoming’s constitutional convention, where mineral taxation was a hot topic. Even in 1889, some delegates saw severance taxes as a way to help save the populace from “burdensome taxation;” others saw a tax as an impediment to development. They compromised by imposing a gross products tax—essentially a personal property tax on produced minerals, according to value—while giving the legislature the authority to set the tax rates.

Years later, a proposed constitutional amendment to impose a severance tax failed in the 1924 election. A majority of those voting on the question approved it, but the amendment went down because it did not receive a majority of the total of votes cast in the election. Several subsequent legislative efforts also were unsuccessful.

Wilkerson’s campaign revisits the severance tax

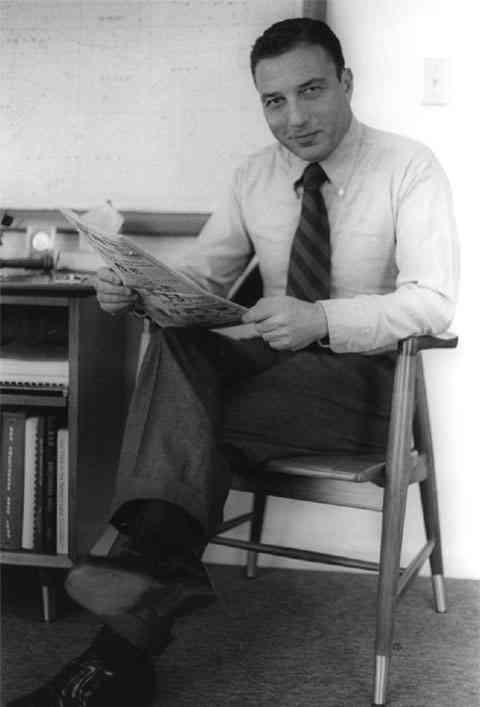

In 1966, Ernest Wilkerson’s gubernatorial campaign refocused public attention on a severance tax. Campaigning with the slogan, “Wyoming’s Wealth for Wyoming’s People,” Wilkerson referred to “the quiet siphoning of Wyoming’s wealth” and foresaw the potential of mineral/energy development in the state.

Wilkerson’s background made him well suited to running a campaign statewide. He distinguished himself as a debater at Natrona County High School in Casper, Wyo. and went on to become student body president at the University of Wyoming. He served with distinction in the South Pacific during World War II. He graduated from Yale Law School in 1948 and returned to Casper to practice law, specializing as a plaintiff’s lawyer in personal injury cases.

Wilkerson’s law practice was successful. He also inherited a profitable business, Wyoming Automotive Company, a chain of Wyoming auto-parts stores founded by his father, W.F. Wilkerson. He eventually sold the stores to their local managers—even financing the sales if necessary—and refused offers from several out-of-state corporations to buy the business.

Though the job of university student body president is for many the first rung on the ladder of politics, Wilkerson did not climb any more rungs for many years. He was involved in local business ventures and was elected to the Casper City Council, but he did not pursue the higher offices that many thought he should.

Wilkerson’s friend and colleague, the late Congressman Teno Roncalio, thought Wilkerson’s own involvement with campaigns—particularly John F. Kennedy’s triumphant 1960 presidential run—and Roncalio’s successful run for Congress in 1964 finally focused his fellow Democrat Wilkerson’s attention on running for office himself.

Wyoming’s Democratic Party was flying high after the 1964 election, when it enjoyed successes not seen for many years before and not seen since. Moreover, the state’s economy in 1966 provided a good launching pad for a candidate with a good business background and an interest in issues. Revenue problems loomed on the horizon, and Wilkerson had some ideas on what to do about them.

He published several of his ideas in pamphlets and newspaper advertisements. John Hinckley, a political science professor at Northwest College in Powell, Wyo., described them at the time as “brilliant small essays on public policy,” while Mike Leon, editor of the Spokesman, the Wyoming Democratic Party newspaper, called them “incomprehensible—a lawyer’s production.” Certainly they stretched the attention of the voting public in 1966 and would be completely unusable in today’s sound-bite campaigns.

Wilkerson faces Hathaway in gubernatorial bid

After winning a five-way Democratic primary, Wilkerson faced Republican Stanley K. Hathaway of Torrington, who had followed a more conventional path to his candidacy. Also a lawyer, Hathaway began his political career by winning the race for Goshen County attorney in 1954 and was re-elected in 1958. He served as state chairman of the Wyoming Republican Party from 1964-1966, a good start for a statewide race. He had planned to run for a seat in the Wyoming Senate until friends and party officials persuaded him to run for governor. He won a three-way primary to become the Republican standard-bearer in 1966.

Hathaway, no intellectual slouch himself, said of Wilkerson: “He challenged you mentally all the time.” Wilkerson and Hathaway faced off in two televised debates, the first Wyoming gubernatorial candidates to do so. Wilkerson, who Hathaway said “looked like a governor,” also had substantial debating prowess. Hathaway mitigated these risks by negotiating a debate structure of three-minute answers, which hampered the detail-oriented Wilkerson in getting to his points.

Wilkerson and the entire Democratic statewide slate put together a brochure titled, “Let’s Make Wyoming Minerals Make Wyoming Payrolls … Some Ideas.” These included a tax on crude oil exported from Wyoming, but forgiven on oil refined in Wyoming; preferential assignment of state mineral leases to companies processing their product in Wyoming; a severance tax, with revenue earmarked to permanent funds and investments in education and other state and local government functions; and a study of taxing minerals-in-place as a means of stimulating production.

Hathaway derided the proposed study as unconstitutional and ignored the rest, earning a chiding editorial from the Casper Star-Tribune in mid-October. But Hathaway did not have to deal with Wilkerson by himself. Toward the end of October 1966, a mysterious “Committee to Save Jobs in Wyoming” began newspaper, radio and television advertisements against a severance tax and urging voters to elect Hathaway. The committee’s members did not have to declare themselves as there were no campaign reporting requirements at the time.

The 1966 election rudely awakened Wyoming Democrats from their 1964 dreams. The entire statewide slate—including Congressman Roncalio’s bid for U.S. Senate—was defeated and its state legislative gains substantially reversed. Wilkerson received more votes for governor than any previous Democratic candidate, but Hathaway still carried the election by more than 10,000 votes.

Wilkerson forges ahead for the tax

But despite his loss, Wilkerson continued to stoke the public pressure for a severance tax generated by his campaign. The 1967 Legislature increased sin and sales taxes while turning back a proposed 3 percent severance tax on oil and gas.

But as T.A. Larson notes in his History of Wyoming, “In 1969 the pressure for a severance tax became so great that one per cent had to be conceded. State government had to have more revenue, and the alternatives, higher sales tax or an income tax, were even more dangerous politically. Some observers suggested that Ernest Wilkerson’s advocacy of severance taxation in 1966 had educated the public and made severance taxation possible.”

The 1 percent did not come easily, however. Hathaway set the stage with a 1969-71 biennial budget that projected spending at $8 million above projected revenues, and in his 1969 budget message to the Legislature, proposed a 1 percent severance tax on all extractive minerals. No legislators leaped to bring forward his proposal, however. Hathaway recalled in an interview years later that on the last day for bills to be introduced, the chairman of the House Revenue Committee, Campbell County Republican Cliff Davis, called him and said, “I’m going to introduce your bill for you, Governor, because I feel sorry for you.”

The House Revenue Committee then held a hearing on the severance tax bill. Only Ernest Wilkerson testified in favor of it. Five mineral industry lobbyists fulminated against it, to the point that even the Casper Star-Tribune, which had not backed Wilkerson’s candidacy nor supported his severance tax proposals only two years earlier, vehemently declared, “We intend to record for posterity every vote on this bill. We intend to let the people know who were for the people and who were for the industrial giants.”

The people prevailed—or at least the people as the Star-Tribune perceived them. The House overwhelmingly passed the severance tax bill on a 47-10 vote, with the Senate following on the last day of the session, 20-10. Attempts were made in both houses to direct all or part of the severance tax revenues into permanent funds, but these efforts were unsuccessful. Sen. David Hitchcock, D-Albany, presciently “predicted that the discussion over the permanent fund will continue until that proposal is adopted,” the Star-Tribune reported on Feb. 23, 1969.

Lawmakers debate establishment of permanent fund

Five years later, Hitchcock’s prediction came true, in spades. Governor Hathaway, now nearing the end of his second term, started the ball rolling in his message to the Legislature in January 1974:

“In looking at the total picture, I would urge you first of all to enact in this session a constitutional amendment which establishes a mineral severance or excise tax for the permanent funds of this state. And I say constitutional amendment because if we are really looking at future generations, if we want to give them some resource out of the depletable minerals of this state, it must be tied into a constitutional amendment. Otherwise, some legislature at some specific time might get selfish and decide to spend all of that fund at one time. I feel strongly, very strongly, that any increase in the severance tax should be accompanied by a constitutional amendment setting aside a permanent fund, and that the income from that fund should be used by this and future legislatures for impact aid, for water development, for many different things that this state does and will need.”

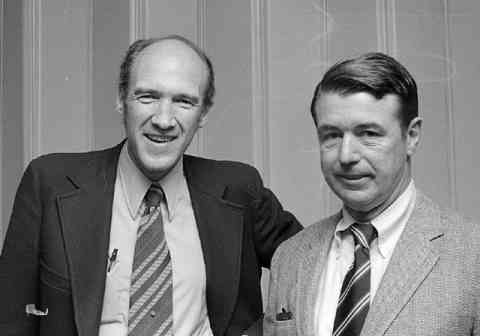

Former U.S. Sen. Alan K. Simpson, who was a member of the Wyoming House of Representatives from Park County from 1965-1977, credits Rep. Warren Morton, who helped guide passage of the 1969 severance tax, with crafting the bill for the constitutional amendment. Simpson recalled in a 2015 interview that he was summoned to a meeting with Morton and state Sen. Thomas F. Stroock. Both Morton and Stroock were from Casper and were professionals in the oil and gas industry.

According to Simpson, Morton said, “’I’m in the oil patch, as is Stroock. When the product is gone, [the oil companies will] be gone, and that’s the way it works. I have in mind a constitutional amendment for a permanent mineral trust fund in which the principal will remain inviolate.’” Simpson said, “Sounds good to me” and explained that he, Stroock and Morton “made the language right there that day.”

Simpson had been among the handful of legislators who voted against the initial 1 percent severance tax back in 1969. “I was from Husky country,” he said, referring to the Husky Refining Company, at that time headquartered in Cody. “I worked there in the summers … it didn’t seem like a good idea to impose a new tax on them.” Simpson remembered also that “Stanley [Hathaway] gave me hell.”

But a couple of years and the state’s pressing revenue needs made the constitutional amendment and a severance tax increase “a pretty good sell” in 1974, said Simpson. As it turned out, a broad majority of legislators went along with both proposals.

Simpson remembers little opposition from the oil and gas industry. Oilmen Morton and Stroock were leaders in the effort to enact the Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund and fill it with severance tax revenues, but many in that industry reacted predictably. James A. Masterson, part of the Casper oil and gas industry, captured the typical stance in a letter to Stroock, who chaired the Senate Mines, Minerals and Industrial Development Committee during the 1974 Legislature.

Masterson fumed: “The Casper Star Tribune for January 24, 1974, carries the headline, ‘Stan drops bomb, backs mineral tax’ [referring to Governor Hathaway]. This should have read ‘Stan drops atom bomb’ for it will certainly be a catastrophe if the Wyoming severance tax on oil and gas production is increased …”

The constitutional amendment, offered as House Joint Resolution 2, to distinguish it from a bill, created the Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund. It was sponsored by Reps. Harold Hellbaum (R-Platte County) and Warren Morton. Rep. Hellbaum was a farmer and rancher who subsequently served as speaker of the House in 1975-1976. Morton also later served as speaker during the 1979-1980 biennium.

House Bill 36, sponsored by Simpson and Hellbaum, raised Wyoming’s severance tax to 4 percent. The constitutional amendment and the severance tax increase were worked on close together in time and each with an eye to the other. Both passed by substantial margins.

The Wyoming Legislature’s enthusiasm for the constitutional amendment presaged that of the general public. Unlike the constitutional amendment for a severance tax offered 50 years earlier, the 1974 proposal not only enjoyed overwhelming public support, with 78,842 votes for and 32,414 against, but also easily passed the bar of the majority of votes cast in the election (66,187 votes constituted a majority of the 132,371 votes cast).

The new constitutional amendment provided for a permanent 1.5 percent severance tax on coal, oil, natural gas, and oil shale, and any other minerals designated by the Legislature. The 1.5 percent was to be in addition to any other taxes the legislature might levy, with proceeds to go into a new “Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund, which fund shall remain inviolate.” Income from investing the new, permanent fund would be deposited annually in the general fund.

As noted by Robert Keiter and Tim Newcomb in The Wyoming State Constitution, A Reference Guide, this new constitutional provision joined with two others on property taxes to establish Wyoming’s mineral taxation system as it stands today.

In his address to the 1974 Legislature, Hathaway dared to hope that “We could indeed see a permanent fund of a billion dollars, perhaps two billion dollars by the end of the century.” Indeed, rising energy prices brought the balance of the Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund (PWMTF) to $1.63 billion by fiscal year 2000, and as of June 30, 2014, the fund had a market value of nearly $7 billion. Interest generated by the PWMTF amounted to about $395 million for fiscal year 2014, and is the second-largest source of revenue to the state’s general fund, after sales tax.

Wyoming’s reliance on mineral revenues for a significant part of its budget has proved both a blessing and a curse. Because severance taxes are included in energy prices, the “export” of taxation to energy consumers outside the state has enabled Wyomingites to enjoy a level of state services far beyond what is paid for with their property and sales taxes.

But the boom-and-bust nature of the energy industry inevitably has resulted in state budget booms and busts in Wyoming. Successive legislatures have both increased and reduced severance taxes on different minerals and collectively created a Byzantine system of “rainy day” accounts, containing mineral-derived funds that can be accessed—as opposed to the inviolate PWMTF—in an effort to level out these fluctuations.

Although the PWMTF balance appears to be a lot of money, if mineral revenues screeched to a halt tomorrow, it suddenly would look not nearly big enough. Wyoming residents continue to face the challenge of diversifying the state economy and raising sufficient revenues to fund the services they expect.

Yet many would agree with the observation of the late Justice John Rooney, chair of the Wyoming Democratic Party from 1964-1970, who wrote:

“Although Ernest did not win the election, I believe he did win his crusade on Mineral tax and that the enactment of last session [referring to 1969] was a result of his campaign. True, it was less than the desired amount – but history will record the enactment as Ernest’s accomplishment …”

Editor's Note: We extend special thanks to the University of Wyoming’s School of Energy Resources for support for this and other articles in an ongoing series on the history of Wyoming’s energy and extraction businesses.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Fortieth State Legislature of Wyoming. Digest of Senate and House Journals of the Fortieth State Legislature of Wyoming. Cheyenne: State of Wyoming, 1969.

- Forty-Second State Legislature of Wyoming. Digest of Senate and House Journals of the Forty-Second State Legislature of Wyoming. Cheyenne: State of Wyoming, 1974.

- Gordon, Mark, state treasurer, and Sharon Garland, deputy state treasurer, and Michael Walden-Newman, chief investment officer. Wyoming State Treasurer Annual Report for the Period July 1, 2013 through June 30, 2014.

- Hathaway, Stanley K., governor of Wyoming. Governor’s Message to the Legislature, January 23, 1974, in the Digest of Senate and House Journals of the Forty-Second State Legislature of Wyoming. Cheyenne: State of Wyoming, 1974.

- Hathaway, Stanley K., personal interview with author, August 3, 1988.

- Lummis, Cynthia M., state treasurer, and Sharon Garland, deputy state treasurer, and Glenn Shaffer, chief investment officer. Annual Report of the Treasurer of the State of Wyoming, for the Period July 1, 1999 through June 30, 2000.

- Masterson, James, letter to Thomas F. Stroock, Jan. 24, 1974. Thomas F. Stroock Papers Box 7, Folder 2. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- Roncalio, Teno, personal interview with author, June 24, 1987.

- Rooney, John, letter to Mayne Miller, September 3, 1970, copy in author’s collection and collection of Justice John Rooney.

- Simpson, Sen. Alan K., personal interview with author, February 26, 2015.

- Wyoming Legislative Service Office. 2015 Budget Fiscal Data Book. Cheyenne: Legislative Service Office, 2014.

- Wyoming Secretary of State. 1975 Wyoming Official Directory and 1974 Election Returns. Cheyenne: State of Wyoming, 1975.

Secondary Sources

- Gorin, Sarah. “Wyoming’s Wealth for Wyoming’s People: Ernest Wilkerson and the Severance Tax, A Study in Wyoming Political History.” Annals of Wyoming, 63, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 14-27. A grant from the Wyoming Council for the Humanities financed the research for this article.

- Keiter, Robert and Tim Newcomb. The Wyoming State Constitution, A Reference Guide. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1993, 218.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming, 2nd edition, rev. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, 560.

- Trenholm, Virginia Cole, ed. Wyoming Blue Book, vol. 3. Cheyenne: Wyoming State Archives and Historical Department, 1974, 13.

Illustrations

- The photos of Ernest and Margaret Wilkerson, Stan Hathaway, Tom Stroock, Alan Simpson and Warren Morton are all from the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks. The Wilkerson photo is from the center’s Frances Seely Webb collection, the Hathaway photo is from the Casper Chamber of Commerce collection; and the Stroock and Simpson-Morton photos are from the Casper Journal Collection.

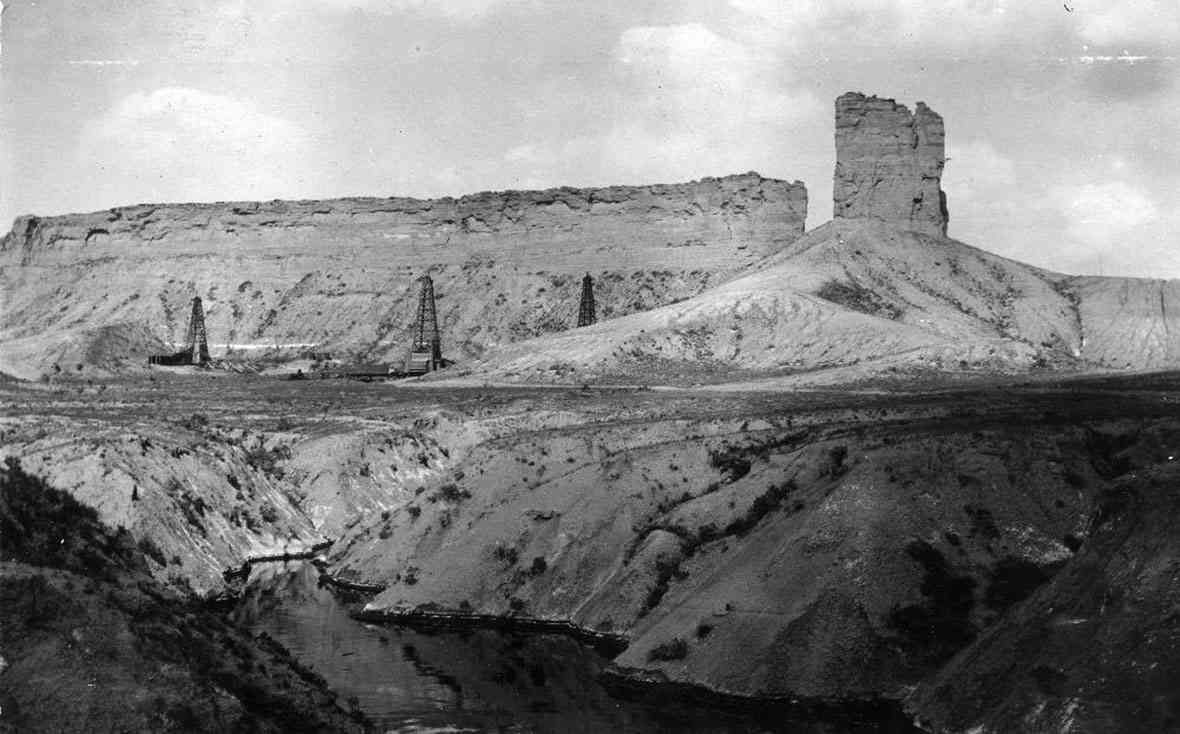

- The 1922 photo of the oil derricks in the Salt Creek oil field is from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Denver Library Photographic Collection. Used with thanks.