- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Wind River Expose In 1980s Led To National Oil ...

Wind River Expose in 1980s Led to National Oil and Gas Reforms

In the 1970s, people on the Wind River Indian Reservation began wondering about the many oil trucks driving through the tribal oil fields at the time and filling up. Were the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes getting paid for all that oil?

Rumors flew. A ditch rider checking an irrigation ditch reported suspicious oil tankers to his supervisor. Shoshone Wes Martel organized shifts to count and photograph tankers, and an oil field roughneck told them, “Don’t you Indians come out here and get yourselves hurt.”Another Shoshone, Stanford St. Clair, and his wife and young daughter were out on a hunting trip when they saw a truck being filled and stopped to watch. The driver shot at St. Clair, who shouted at his family to hit the floor while he sped away.[1]

The situation continued for years. Then on June 13, 1980, a federal oil field inspector named Chuck Thomas, acting on a hunch, pulled an oil tanker driver to the side of the road to check his paperwork and discovered he didn’t have any. Thomas worked for the U.S. Geological Survey, which was responsible for preventing thefts of federal and Indian oil, so he reported the incident to his supervisors. [2]

Nothing happened: Big bureaucracies naturally resist change. In this case, however, Thomas was a whistle-blower who would not give up. Being Cherokee, he might have been personally concerned about the theft of Indian oil. Thomas reported the incident to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Then he and several young tribal members went to the press. Articles appeared in Denver newspapers and The New York Times, and the U.S. Senate held hearings. Within two years, Congress had passed a law, created a new agency to account for federal and Indian royalties and removed USGS from the inspection job. The Wind River Indian Reservation tribes had changed the history of oil and gas development across the country.

Importance of oil and gas revenue

Oil and gas revenue has been crucial to the lives of the tribal members for more than a century. Even though both the Shoshone and Arapaho now have casinos to generate income, Northern Arapaho Business Council member Dean Goggles said, “Oil and gas are our bread and butter.”[3] The median income for reservation households (including Indian and non-Indian) was only $18,000 in 2009, the last year for which figures are available.[4] Claire Ware, director of the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes Minerals Compliance Office, explained, “Our people are struggling.”

Royalties to the tribes have ranged between $23 million and $31 million annually in recent years, Ware said. Fifteen percent of the royalty revenue goes to the tribal governments and 85 percent to individual tribal members as per capita payments—dividends paid to mineral owners. The per capita portion of $23 million totaled $19.55 million, which was divided among 14,000 tribal members. Each Arapaho, though, receives much less than each Shoshone because there are about 10,000 Arapaho and only about 4,000 Shoshone, and the payments are divided evenly between the two tribes.[5]

History of mineral development on the Wind River Reservation

So how did the tribal ownership of lucrative oil and gas resources evolve, and why is so much distributed per capita? The Wind River Indian Reservation, first known as the Shoshone Reservation, was established in 1868, but gold had been discovered in the South Pass area of the reservation already by then. In those years during and after the Civil War, the U.S. military dramatically reduced its efforts to protect Indian lands in the West.[6]

Image

In 1872, the government reduced the size of the reservation to cut out the gold fields, a move the U.S. Indian commissioner justified by saying he wanted to protect the Indians from the miners. The Shoshone tribe received a pittance for the land and nothing for the gold.[7] In 1878, the Northern Arapaho people were placed on the Shoshone Reservation. As a result, the two tribes had to work together to manage their undivided interests in the land, minerals and timber.[8]

In 1891, Congress authorized mineral leasing of tribal lands across the country and provided for token consent. This meant that the oil and gas fields could not be taken as the gold had been, and tribal oil leases were soon signed at Wind River.[9] (Interestingly, this 1891 law meant that Indian lands could be leased 29 years before oil and gas could be leased on federal lands. Until Congress passed the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, companies actually could acquire federal lands with minerals, not just lease them.

The tribes did not benefit from the oil and gas lease revenue, however. On the Wind River Reservation, tribal members were literally starving and living in tents while the Indian Bureau used the tribal oil revenue for agency telephone lines and salaries, according to historian Loretta Fowler. The government provided rations as required by their treaties. But the rations were scant—starting at one pound of beef and ten ounces of flour per person per week—and the government gradually reduced even that. Tribal members were not allowed to hunt outside the boundaries of the reservation, and game was scarce on the reservation because of cattle owned by non-Indians grazing there.[10]

While non-Indians often romanticize American Indians as environmentalists protecting Mother Earth at all costs, economic realities usually demand a more pragmatic approach to reservation resources. In 1905, the Arapaho wrote to the Indian commissioner, seeking someone who would help them find minerals on Indian land: “Please send out a good friend of the Indians to find them mines. We give them 15 cents for every dollar.”

The tribes wanted the lease income distributed per capita—so that the funds would be paid directly to individual tribal members instead of flowing to the federal government. But the federal government refused. This drove the tribes at one point to vote not to allow any more leasing unless the proceeds were divided among tribal members.

For decades, tribal leaders continued this fight. In his appeal in 1911, Arapaho councilman Yellow Calf said, “We made these leases for our children, for the old and helpless, and for those who can’t work … Probably God has made the Indians just like the white man, and I do not understand why the government did not ask us if they could use this money.”[11] Finally, in 1947, Congress passed special legislation for the Wind River tribes providing for per capita payments from tribally owned leases.[12]

By that time, under the so-called allotment system, the federal government had opened many reservations across the West to homesteading and had divided up remaining land among individual Indians. In 1905, more than 1.5 million acres of the Wind River Reservation were ceded by the tribes and opened to homesteading, and more than 100,000 acres were allotted to individual Indians. The mineral rights to the ceded portion were returned to tribal ownership in 1958, but individual Indian allottees still own their own minerals, further complicating royalty accounting and inspections.[13]

Investigations and reforms

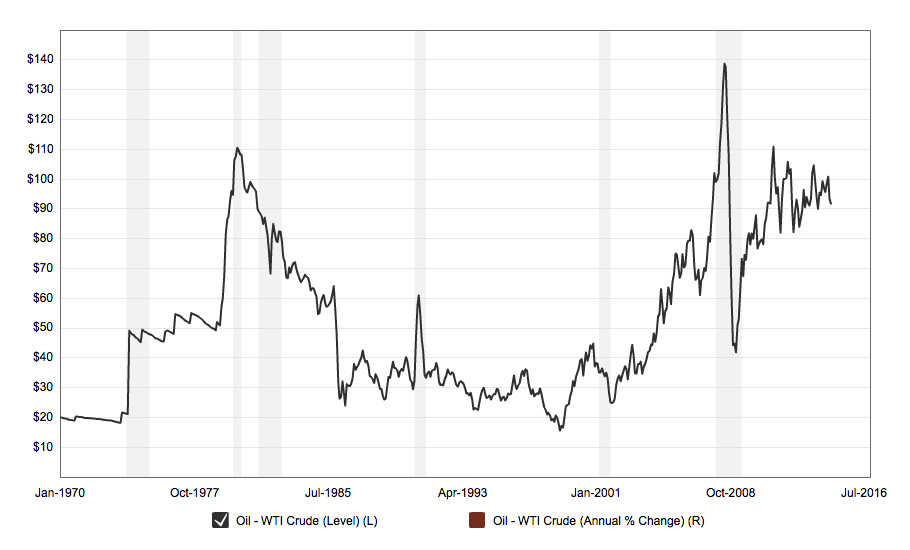

Between 1874 and World War II, the average price of oil rarely rose above a dollar per barrel.[14] Prices rose fast after the Arab oil embargo of the early 1970s, however, and when President Reagan lifted price controls in 1981, the reward for theft became much higher. Investigators revealed that federal oil had been mismanaged as much as the Indian oil, but that provided little solace to the tribes, who, like the states, needed the full value of their royalty income to help provide basic government services. Tribes across the country also suffered from the loss of federal grants and contracts to provide government services during the 1980s under the Reagan administration. Once again, the tribes and their members were oil rich but penny poor.

The Linowes Commission, appointed in 1981 by U.S. Interior Secretary James Watt to investigate, found existing federal regulations had not been enforced and confirmed that USGS needed more inspectors, better training methods and supervisors with more backbone. In some cases, the oil companies’ poor security measures exposed the companies themselves to theft.

The efforts to reform Indian and federal oil and gas development suffered from serious flaws, which was not surprising given the speed with which the reforms were enacted. The Minerals Management Service (MMS) was created on Jan. 21, 1982, just a year and a half after the oil thievery was discovered on the Wind River Reservation. By the end of 1982, Congress passed the Federal Oil and Gas Royalty Management Act (FOGRMA) and shifted the inspection responsibility from the USGS to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).[15]

At first it looked as if the site security investigations would result in many convictions across the country. Thousands of citations were issued to oil companies. In one especially notorious case, a jury in 1999 found Koch Industries guilty of stealing oil from federal and Indian leases; Bill Koch said his brothers profited by at least $230 million.[16] Without the help of insiders like Bill Koch, however, it was difficult, for many reasons, to prove oil had been stolen.

Chuck Thomas, in his testimony before Congress, described the USGS inspection system as an unminded store, but the situation was even worse. Because well production was not checked regularly by the USGS, the store owner had no baseline inventory to know what was missing. The old records were so inaccurate that when MMS employees tried to reconcile them, the auditors wrote off any balance under $100,000. With the focus on the interests of the states and tribal governments, the individual mineral owners—the allottees—were ignored in the reforms.[17]

The idea of thieves filching truckloads of oil, especially from Indians, captured the nation’s attention, but most of the provable losses turned out to be the work of a sharp pencil, not a pipe wrench. Some companies eventually made large settlements; a few were fined. The 1980s Wind River exposé contributed later to the rationale for the national Cobell lawsuit on behalf of individual Indian allottees, and various lawsuits against the Department of Interior on behalf of tribes over the federal government’s failures to protect their trust assets—such as oil, gas, timber and agricultural lands.[18]

Tracking the revenue flow

The 1982 FOGRMA was one of the first laws that provided tribes the same authority as states.[19] This was followed by provisions for Indian tribes in major environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act.

At Wind River, three well-educated staff members, two of them American Indians, are now responsible for ensuring that the tribes are paid appropriately for their oil and gas. The Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes Minerals Compliance Office was established in 1994 under Section 202 of FOGRMA to help verify that companies are paying the appropriate royalties. The Minerals Compliance Program is funded by the federal Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR), which was formerly the Minerals Management Service. Claire Ware, a Shoshone, has directed the tribal compliance office since 2007, and the auditors are Gabriel Flagg, CPA, and Stefan Reed, an unaffiliated Northern Ute, both of whom have master’s degrees in business fields. At the national level, Ware also serves on the ONRR Indian Oil Negotiation and Rulemaking Committee.

Ware and her staff match figures provided by companies, most of which now use electronic reporting, to different agencies and watch for discrepancies. Then they go into the field with the BLM and Bureau of Indian Affairs representatives to verify measuring points, site security and meter calibrations. When they discover problems, the ONRR employees conduct further investigations. If the companies do not comply, they incur fines and penalties.[20]

Image

Because there are too many leases and wells to check each year, both the tribal compliance office and BLM rely upon a risk formula to prioritize their efforts. The BLM inspects both federal and Indian oil and gas fields. In the Lander District, where the Wind River Reservation is located, four BLM employees are responsible for inspecting about 1,000 Indian wells and 1,200 federal wells. The Bureau of Indian Affairs’ (BIA) role is limited to surface issues, such as reclamation and environmental conditions. According to representatives of both the tribes and the BLM, oil and gas management has improved dramatically since the early 1970s. Nevertheless, the situation is far from perfect, as shown by recent investigations conducted by federal agencies and the press. [21]

Only about half (55 percent) of the newly drilled, high priority leases on federal land in Wyoming are being inspected by the BLM, The Associated Press reported on June 14, 2014. BLM spokesperson Cindy Wertz blamed the problems on congressional budget cuts. The federal agency is not able to compete with higher salaries paid to inspectors by private industries.[22] Tribal inspectors could stretch the resources of the BLM Lander District through a FOGRMA Section 202 agreement, similar to that between the tribes and the ONRR. Although the tribes and the BLM have considered this option several times throughout the years, various logistical and financial obstacles on both sides have prevented it from happening, according to BLM District Resource Advisor for Energy Stuart Cerovski. [23]

Future development of resources

The tribes have slightly reduced their dependence on oil revenue through diversification. Construction of grocery stores, gasoline stations and casinos has also provided income sources. More recently, the establishment of a broadband and telephone company and the creation of a conference center have helped. The tribes are also considering alternative energy development— hydroelectric, solar and wind—according to Gary Collins, the Arapaho Tribe’s liaison with Wyoming state government and a former member of the tribal business council.[24]

The quantity of oil being produced on the Wind River Reservation has dropped over the years, but the rising price per barrel, which has more than quadrupled in real terms since the mid-1970s, has more than made up for the loss. Recognizing that existing wells will deplete the reservoirs, tribal representatives have asked BLM and BIA analysts to conduct studies on the undeveloped reservoirs’ value. Because of past problems, tribal officials remain wary about signing new leases or engaging in joint ventures with oil companies, especially until after they have received a reliable reservoir analysis.

For now, the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes are focused on ensuring they receive all the revenue to which they are entitled. No matter how dedicated another person might be, tribal members bring a personal interest to this work that others might lack.

Claire Ware, Shoshone tribal compliance director, vividly remembers the shots aimed at her family’s car back in the 1970s even though she was just a child at the time; her father was Stanford St. Clair. Ware said, “When I took the job, I wanted to find out if anything was being stolen. On the one hand, I see all that oil and gas, and on the other, I see my people struggling.”

Timeline

- 1868 — Shoshone Reservation established

- 1872 – Shoshone Tribe loses 601,120 acres of land around South Pass after discovery of gold there.

- 1878 — Northern Arapaho people placed on the Shoshone Reservation.

- 1891 — Congress authorizes mineral leasing of tribal lands across the country and provides for token consent.

- 1900s – Until World War II, the average price of oil rarely rises above a dollar per barrel

- 1905 – Wind River tribes forced to cede more than 1.4 million acres of their reservation for potential homesteading.

- 1938 – The U.S. Government pays $4.5 million to the Eastern Shoshone for reservation land occupied by the Northern Arapaho.

- 1947 — Congress passes special legislation for the Wind River tribes providing for per capita payments from tribally owned leases.

- 1958 – Congress restores to tribal ownership the minerals within the area ceded in 1905.

- 1971 – Price of oil at less than $3 per barrel

- 1980 — Wind River exposé of oil thefts; Wind River Indian tribes hire former USGS inspector Chuck Thomas as employee; price of oil increases to $110 per barrel.

- 1981— U.S. Senate holds oil theft hearings in Billings, Mont., and Shoshone Tribe presents testimony.

- 1982 – Congress passes FOGRMA, creates Minerals Management Service, shifts field inspections from USGS to BLM.

- 1984 — Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes Minerals Compliance Office created under cooperative agreement with MMS.

- 2008 – Oil prices peak at $138 per barrel.

- 2009 — Oil prices dropped to $41 per barrel.

- 2010 — Office of Natural Resources Revenue created to take over responsibility from MMS

- 2014 — Price of oil rises to more than $100 per barrel.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Arapaho Business Council members, interview by author, Ethete, Wyo., May 20, 2014.

- Cerovski, Stuart. resource advisor, Lander Field Office, U. S. Bureau of Land Management, interview by author, Lander, Wyo., May 21, 2014.

- Collins, Gary, Northern Arapaho tribal liaison to the state of Wyoming, telephone interview by author, June 23, 2014.

- U.S. Government Accounting Office, “Oil and Gas Development: BLM Needs Better Data to Track Permit Processing Times and Prioritize Inspections,” Report to Congressional Requesters, August 2013. Accessed Aug. 17, 2014 at http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/657176.pdf

- Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of the Interior. “Office of Enforcement, Office of Natural Resources Revenue Report No. CR-EV-MMS-0002-2010,” Jan. 2012. Accessed Aug. 17, 2014 at http://www.doi.gov/oig/reports/upload/CR-EV-MMS-0002-2010Public.pdf

- Yen, Hope and Thomas Peipert. “Wyoming heads nation's list of unchecked oil and gas wells,” The Associated Press, June 14, 2014. Accessed Aug. 17, 2014 at http://trib.com/business/energy/wyoming-heads-nation-s-list-of-unchecked-oil-and-gas/article_f3d85feb-56bc-57ea-803c-6ca71b417c8a.html

- Ware, Claire, director, Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes Minerals Compliance Office, interview by author, Fort Washakie, Wyo. May 20, 2014.

Secondary Sources

- Ambler, Marjane. Breaking the Iron Bonds: Indian Control of Energy Development. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990.

- Fowler, Loretta. Arapahoe Politics, 1851-1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

- “Historical Crude Oil Prices (Table).” Accessed Aug. 17, 2014 at http://inflationdata.com/Inflation/Inflation_Rate/Historical_Oil_Prices_Table.asp.

- O’Gara, Geoffrey. What You See in Clear Water: Indians, Whites, and a Battle over Water Rights in the American West New York: Vintage Books, 2002.

- Royster, Judith V. “Mineral Development in Indian Country: The Evolution of Tribal Control over Mineral Resources.” Tulsa Law Review 29:3, 1994, Energy Symposium. Accessed Aug. 17, 2014 at http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2276&context=tlr.

- Sutton, Robert K. and John A. Latschar, eds. American Indians and the Civil War: Official National Park Handbook. National Park Service, 2013. Accessed Aug. 17, 2014 at http://www.aianta.org/uploads/FileLinks/7f75e38b53ce426fa8db963f94d19726/AICW_FLYER.pdf.

Illustrations

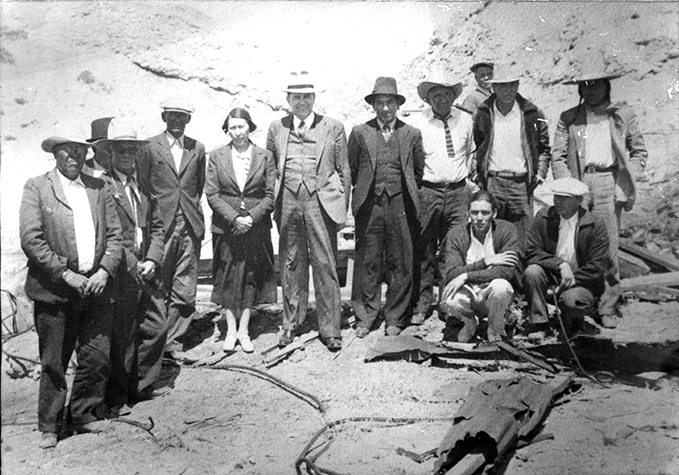

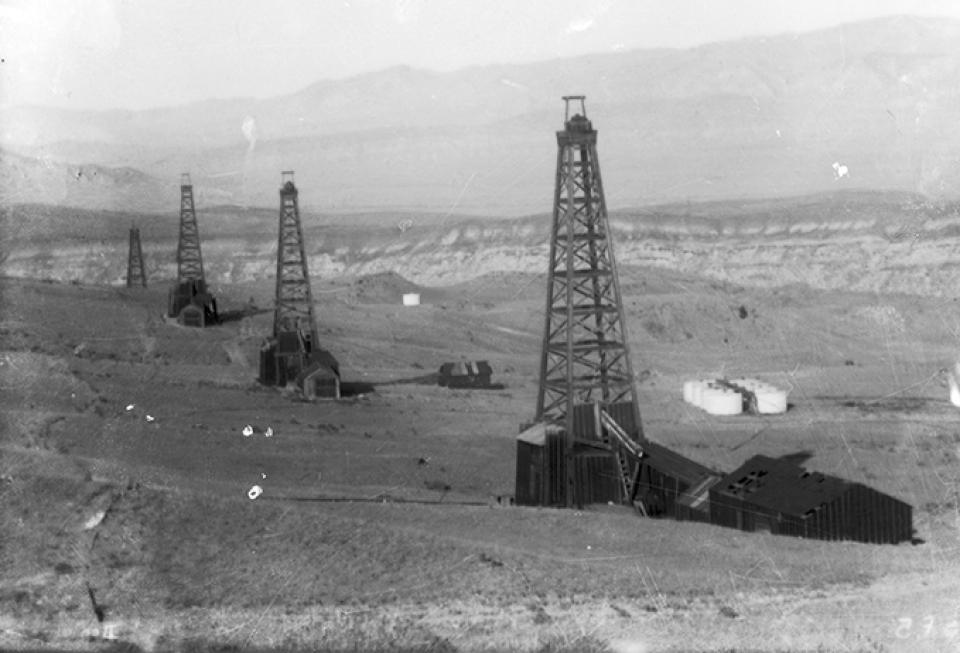

The early photo of the derricks on the Maverick Springs oil lease, and the1938 photo of members of the Shoshone and Arapaho Business Councils with Assistant Secretary of the Interior Oscar Chapman are from the collections at Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Used with permission and thanks. Arapaho officials pictured on the left are John Goggles, unidentified, Charlie Whiteman, Robert Friday and Nell Scott. The man with the white hat in the center is probably Chapman. To his left are Shoshone officials Gilbert Day, Ben Perry, Bill McAdams, Frank Enos, Charlie Washakie and (in front) Robert Harris and Lynn St. Clair.

The other two photos are by Sara Wiles of Lander, Wyo., longtime photographer of subjects on the Wind River Reservation. Used with permission and thanks.

The Crude Oil Price History Chart is from Macrotrends. Used with thanks.

[1] Interview by author with Claire Ware at Fort Washakie, Wyo., 5/20/14; Geoffrey O’Gara, What You See in Clear Water: Indians, Whites, and a Battle over Water Rights in the American West (Vintage Books, 2002), 137.

[2] Marjane Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds: Indian Control of Energy Development (Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1990), 118.

[3] Interview by author with four members of Arapaho Business Council in Ethete, Wyo., 5/20/14

[4] Interview by author with Gary Collins 6/23/14 by telephone.

[5] Claire Ware interview

[6] Robert K. Sutton and John A. Latschar, American Indians and the Civil War, (National Park Service, 2013)

[7] Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 33.

[8] Most Northern Plains reservation lands and minerals are owned by more than one tribal group, usually jointly. Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 187

[9] Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 37

[10] Loretta Fowler, Arapahoe Politics, 1851-1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority (University of Nebraska Press, 1982), 88-89

[11] Fowler, Arapahoe Politics, 91

[12] Fowler, Arapahoe Politics, 87-91; Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 48

[13] Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 53, 166

[14] Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 33

[15] Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 127-131

[16] http://www.cbsnews.com/news/blood-and-oil/ retrieved 6/5/14. Dated 11/27/2000. “60 Minutes”

[17]Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 128, 132. Marjane Ambler, “Oil Rich and Penny Poor,” Denver Post Empire Magazine, October 13, 1985.

[18]The Cobell suit was settled in 2009, shortly before the death of Elouise Cobell, who had dedicated over 30 years of her life to this effort.

[19]Ambler, Breaking the Iron Bonds, 133.

[20] Claire Ware interview 5/20/14

[21] U.S. Government Accounting Office, “BLM Needs Better Data to Track Permit Processing Times and Prioritize Inspections,” August 2013. http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/657176.pdf

Office of Inspector General, “Office of Enforcement, Office of Natural Resources Revenue Report No. CR-EV-MMS-0002-2010,” Jan. 2012,http://www.doi.gov/oig/reports/upload/CR-EV-MMS-0002-2010Public.pdf

[22] “Wyoming heads nation's list of unchecked oil and gas wells,” June 14, 2014, by Hope Yen and Thomas Peipert. The Associated Press, retrieved June 15, 2014. http://trib.com/business/energy/wyoming-heads-nation-s-list-of-unchecked-oil-and-gas/article_f3d85feb-56bc-57ea-803c-6ca71b417c8a.html

[23] Interview by author with Stuart Cerovski, district resource advisor for energy, in Lander 5/21/14

[24]Gary Collins interview 6/23/14.