- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Oil Seeps and Axle Grease: Petroleum Sales On T...

Oil Seeps and Axle Grease: Petroleum Sales on the Emigrant Trails

Axle bearings on the wagons and carts used on the emigrant trails in 1800s needed regular lubrication. Most wagons carried the grease in a hanging bucket. Dusty conditions or excessive use could deplete the carried grease. This created a demand for axle grease among the travelers. The resulting grease trade is thought to be the first commercial petroleum business in Wyoming.

Sources of the grease

Seeps and pools of oil on the surface were the source of the grease. When fur trader Capt. B. L. E. Bonneville traveled to the Wind River Valley in 1832, he found oil springs southeast of present Lander near Dallas Dome. And an oil spring near Hilliard in present Uinta County was well known by the time Fort Bridger was established nearby in 1842.

In what’s now Natrona County, Wyoming, an anticline—an up-fold in rock layers—now called Oil Mountain has a collapsed region at its northwest end. There was an oil seep at the fault and even today there is evidence of oil still visible at the place where the seep was shown on early maps. The site is now inaccessible without crossing private land. Oil no longer escapes there, but the ground smells like crude oil and is saturated with gummy black petroleum.

In pioneer times, grease merchants skimmed oil at the seep and carried it by pony some four miles to the emigrant trail. The crude oil was mixed with flour to make suitably stiff axle grease.

Although no diaries have yet been found that record a purchase of grease by pioneers near Oil Mountain, numerous geologic documents, all written at least three decades after the fact, mention petroleum commerce with emigrants near the Oil Mountain seep.

In the later documents the trade was variously described as having started shortly after emigrants first began using the trail in the 1840s, or in 1849, 1851 or 1863. The reports usually mention famous English-speakers, including frontiersmen Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Jim Baker and, in some cases, even 1880s pioneer oil prospector Cy Iba as the principal grease merchants. The sources also allude to the participation of usually nameless “half-breeds,” who were the mixed-race offspring of early trappers or traders and their Indian wives.

Sgt. Isaac Pennock, Company L, 11th Kansas Cavalry, kept a diary in the spring, summer and fall of 1865, which included careful observations at the times of the battles of Red Buttes and Platte Bridge. He also recorded hearsay about an oil spring near the trail, which soldiers and travelers used.

On May 26, Pennock wrote, “South of Willow Springs is an oil spring said to run 50 barrels of petroleum per day.” With two alterations, Pennock’s report would be consistent with the facts of the Oil Mountain seep. Fifty barrels per day of running petroleum is almost certainly an exaggeration; that much oil would make a great mess anywhere. Second, changing “south” to north locates Oil Mountain, which is five miles nearly due north of Willow Springs. Willow Springs is about 25 miles west of present Casper, Wyo.

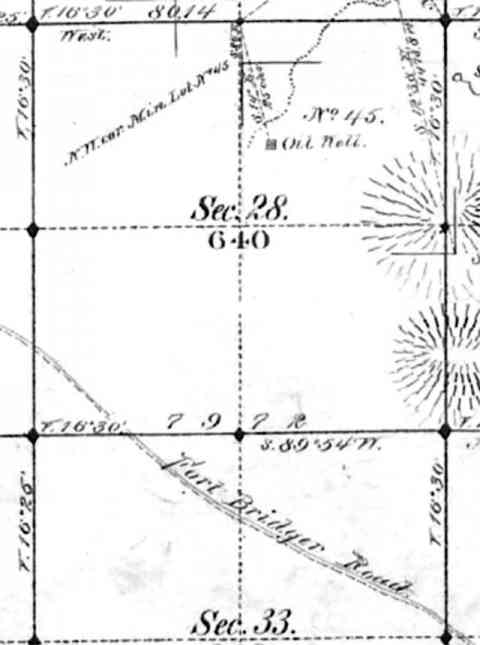

The seep or well began to appear on maps in the 1880s. G.F. Cram’s 1882 Rail Road and Township Map of Wyoming shows a spring of petroleum at approximately the right place in a region that had not been surveyed by the government. A cadastral survey made in 1882 and published in 1883 shows the oil “well” at its correct position.

Mitchell Lajeunesse, a likely grease merchant

John Hunton, Confederate survivor of Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg and an early stockman and diarist in Wyoming Territory, reported years later in an account published in 1920, “In 1873, Mitchell Lajuenesse, son of Bassell Lajuenesse, advised me that he had found oil in the vicinity of the present town of Casper.”

The Lajeunesse family had been well known for years by that time in central Wyoming. Basil Lajeunesse was a voyageur on the early expeditions of explorer John C. Fremont, and is a vivid figure in Fremont’s reports. He was killed in Oregon in 1846 on Fremont’s third expedition to the West. Basil’s brother Charles was for a time bourgeois or chief trader at Fort Laramie, and later, with his associates, ran a toll bridge at Independence Rock and a trading post at nearby Devil’s Gate, on the emigrant trail on the Sweetwater River. Mitchell—the French name would have been Michel—and his brother Noel had a Shoshone mother and were of the next generation from Basil and Charles.

Charles especially, and other members of the family were also called by the name Cimineau, often rendered by English speakers as Seminoe or Seminole. The Lajeunesse children were bicultural by virtue of their French and American Indian families and continuing contacts with other Europeans and their mothers’ tribes.

Diarist Hunton noted that “Little Bat [Baptiste Pourier, another member of the French-named, mixed-race community of central Wyoming] Lajuenesse and I took supplies and set out for this ‘oil field.’ Arriving upon the spot, we at once began operations by ‘spooning’ up the oil. After working industriously for some time, Little Bat and I had acquired about a quart, while Lajeunesse had succeeded in obtaining a smaller quantity of the crude.”

That night, some Arapaho men visited them as they were gathered around their campfire. The Indians told the prospectors they were not welcome in the area, and told Lajeunesse to make sure the party left in the morning and followed the North Platte 75 miles east down river to Fort Fetterman. Some subsequent historians have assumed Hunton was referring to oil springs at what later became the long-lived Salt Creek Oil Field 45 miles north of present Casper. But his reference to the route the Arapaho told the men to take to Fort Fetterman makes it far more likely he was talking about the seep at Oil Mountain.

The prospectors thought it a good idea to comply promptly. “Upon reaching Fort Fetterman,” Hunton notes, “we placed the oil in a bucket of hot water and I found that I had a pint bottle of crude oil.”

The Indians had been in the area for generations—the Shoshone probably for millennia—and they would have known where many oil seeps were. They used the oil medicinally and in paint. Some of the early state and U.S. government geological reports indicate a specific mixed-race person involved in the grease commerce. Robert Morris, in an 1897 report, wrote, “as early as 1863 Seminole collected the oil and sold it for axle-grease.” W. T. Lee noted in 1915, “It is reported that Cimineau, a French trapper, and others sold lubricants to the caravans from the oil spring at sec. 28, T. 33 N., R. 82 W.”

Connections between Jim Bridger, the Lajeunesse family and Oil Mountain are well known. Bridger bought a trading post near Fort Bridger from Charles Lajeunesse in 1852. Bridger is tied to Oil Mountain and the seep areas by the trail he blazed in 1864 trail from what’s now central Wyoming to Montana, as well as reports that he sold grease. The Bridger Trail and the seep were less than one mile apart.

The distance from Independence Rock to the Oil Mountain seep is 31 miles, and most of that could have been traveled along the emigrant trail. The mixed-race persons involved in the grease trade likely came from the communities near Independence Rock and Devil’s Gate, and very likely involved the young Lajeunesse, Michel “Seminoe.”

Other mixed-race offspring from the area could also have been involved. Louis Guinard, who built the bridge at present-day Casper, also had a Shoshone wife and was associated with the community at the Sweetwater Bridge near Independence Rock. John Richard, known as Reshaw, operated in the 1850s from the bridge that bore his name at present-day Evansville and had an Oglala Lakota wife and mixed-race offspring. There is no evidence that Richard’s family traded grease, although they probably knew of the Oil Mountain region on the trail.

Aughey’s report and modern oil development

By the mid-1880s, oil exploration in Wyoming had a scientific basis. Samuel Aughey, the territorial geologist through 1885, wrote a report that Gov. F.E. Warren released in early 1886. He described, among many other things, the characteristics of eight oil basins. Aughey gave directions by road from Jim Averell’s store and road ranch on the Sweetwater to six contiguous townships that he called the Seminole Oil Basin. The basin included, near its center, the oil seep that was four miles from the Oregon Trail.

Aughey switches between “Seminoe” and “Seminole” in his report. He refers to both “Seminoe Mountain” and “Seminoe Ridge” in specifying the locations of the seep and the oil-bearing structure. Apparently the name Oil Mountain was replacing the previously used label, Seminoe Mountain, at the time of his report. Aughey wrote of “the Seminoe or Oil Mountain, as it has been named” and “the Seminoe ridge (Oil Mountain) is itself an anticlinal fold.” Therefore, the region was linked to the Lajeunesses as late as the 1880s.

Aughey found the petroleum in the region to be suitable for production of illuminating oil. He predicted that it was “very probable, that beneath the fault at [a place on Oil Mountain east of the seep] oil in quantity will be eventually found.”

The ground near the historic oil seep was perforated with oil wells between Aughey’s time and at least as late as 1958, but no one ever found a significant source of oil coupled with the seep. However, Aughey’s Seminole Oil Basin has produced much oil and gas. New wells are operating on and near Oil Mountain today. The Iron Creek oil field, on the anticline and in Aughey’s basin, has operated for about a century.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Aughey, Samuel. Report of the Territorial Geologist. In Message of Francis E. Warren, Governor, to the Legislature of Wyoming, Ninth Assembly. Laramie, Wyo.: Boomerang Printing, 1886, 148-152.

- Hunton, John (as told by). Early Oil Discovery in Wyoming. Proceedings and Collections of the Wyoming State Historical Department 1919-1920, First Biennial Report of the State Historian. Laramie, Wyo.: Laramie Printing Company, 1920, 149.

- Lee, W.T., R.W. Stone, H.S. Gale, et al. Guidebook to the Western United States, Part B, The Overland Route. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 612 (1915), 62.

- Morris, Robert C. Sketch of Wyoming. Collections of the Wyoming Historical Society, vol.1, Cheyenne Wyo: Sun-Leader Publishing House, 1897, 37.

- Pennock, Isaac B. “Diary of Jake Pennock.” Annals of Wyoming Vol. 23, No. 2 (1951): 7, accessed April 14, 2015 at https://archive.org/stream/annalsofwyom23121951wyom#page/n127/mode/2up/search/Pennock.

Secondary Sources

- Cram, G.F. Cram’s Rail Road and Township Map of Wyoming. Chicago, Ill.: Geo. F. Cram. 1882.

- David, E.C. Map of Township No. 33 North, Range No. 82. Surveyor General’s Office, Cheyenne, Wyo.. 1883.

- Espach, Ralph H. and W. Dale Nichols. Petroleum and Natural Gas Fields in Wyoming. United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines Bulletin 418, (1942).

- Glass, Jefferson. Reshaw: The Life and Times of John Baptiste Richard. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press. 2014.

- Hares, C. J. Anticlines in Central Wyoming. In Contributions to Economic Geology, United States Geological Survey Bulletin 641 (1916), 239.

- Knight W.C. and E.E. Slosson. Petroleum Series-Bulletin No. 4, The Dutton, Rattlesnake, Arago, Oil Mountain and Powder River Oil Fields. Laramie Wyo.: School of Mines, University of Wyoming. 1901, 32.

- Love, J. D. “Annotated Photographs and Significance of Oil Seeps, Tar Sands, and Pioneer Drilling in the Wind River Basin, Central Wyoming.” In Boyd, Richard G., George M. Olson, and Walter W. Boberg, eds. Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook, 1978: Resources of the Wind River Basin: Casper, Wyo.: Wyoming Geological Association, 1978.

- Rea, Tom. Devil’s Gate: Owning the Land, Owning the Story. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, 64-77.

- Roberts, Phil. “History of Oil in Wyoming.” In A New History of Wyoming. University of Wyoming. Accessed April 8, 2015, at http://www.uwyo.edu/robertshistory/history_of_oil_in_wyoming.htm.

Illustrations

- Reproduction of part of Map of Township No, 33 North, Range No. 82 West…. Surveyor General’s Office, Cheyenne, Wyo., Feb. 23, 1883. Thanks to Reid Miller of the Bureau of Land Management for this image.

- The I.N. Knapp’s photograph of Oil Mountain Seep, Aug. 4, 1899 was originally commissioned by the U.S. Geological Survey and reproduced on p. 64 off the 1978 Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook, Wind River Basin.