- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Cheyenne’s 100-Octane Aviation Fuel Plant

Cheyenne’s 100-Octane Aviation Fuel Plant

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II on Dec. 7, 1941. Within days the United States was at war with Germany and the other Axis powers. War mobilization, already begun in anticipation of America's involvement, went into high gear. The government let huge contracts for the construction of airplanes, ships and every other form of war material. One of the most central needs was for a large, dependable supply of petroleum. This would require industry-government coordination as well as antitrust exemptions so companies could pool resources and operate together.

Getting the maximum performance out of military aircraft required high-octane gasoline, a commodity that had only a limited market before the war because of the cost of manufacture. The fuel, developed by Shell Oil Company researchers in the mid-1930s, increased aircraft performance far beyond the level of 75- or 87-octane fuels customarily used. Such use also provided fuel savings and thus made it possible for planes to fly farther. The fuel had proven its worth in the air war over Britain in 1940 when 100-octane-fueled British Spitfires outperformed German planes powered by 87-octane gasoline.[1]

Because petroleum was so central to a successful war effort, the federal government organized production and consumption systems. The principal agency in charge was the Office of the Petroleum Coordinator, but early in the war some 40 agencies had a say, one way or another, in the petroleum industry. The goal was to maximize the supply while curtailing all nonessential use.[2]

The 100-octane fuel was crucial in the equation, but oil-industry and government officials knew that production of such fuel was vastly more difficult and expensive than for lesser quality gasoline products. Such plants could not be constructed quickly.

Defense specialists believed plants to make the 100-octane fuel should be constructed in the nation’s interior, close to oil fields but away from possible enemy air or sea attack.[3]

Within a month of the onset of war, Cheyenne businessman Maurice H. “Bud” Robineau, president of Frontier Refining Company, began studying the feasibility of constructing a 100-octane plant in Cheyenne. He proposed a 40-acre site adjacent to the Frontier refinery in south Cheyenne near the Union Pacific rail lines.[4] Construction and operation of such a facility would require significant government assistance. Not only would the plant need government approval to divert oil supplies for its needs, but it also would have to gain government priorities for steel and other construction materials in demand in all sectors for the war effort.

|

Robineau enlisted the help of Wyoming's senior U.S. senator, Joseph C. O'Mahoney. A member of the majority Democratic Party who had been in the Senate since January 1934, O'Mahoney wielded significant influence with federal agencies involved in making war allocation decisions. As the construction of the 100-octane plant in Cheyenne would demonstrate, O'Mahoney was more than an ardent advocate for increased appropriation for military installations in Wyoming. “He labored indefatigably in behalf of Wyoming’s small business, agriculture, livestock and mineral industries,” historian T.A. Larson notes.[5]

Robineau told O'Mahoney that he had already located dependable sources of oil from which the aviation fuel could be made. He discussed the prospects with Duff Gray, owner of Gray Refinery, Inc., of Newcastle, who agreed to furnish the necessary raw product. Other refineries in Wyoming—C&H at Lusk, Z&W at Torrington and Albany Refining at Laramie—would be likely sources too, Robineau believed.[6] In the deal with Gray, Robineau agreed to buy 500 barrels of oil daily from Gray’s refinery to be shipped to Frontier Refining in Cheyenne. That would be only part of what the new plant would need.

In return, Robineau would ship 70-octane unleaded gasoline from Frontier to Newcastle, which Gray would then sell to his customers.[7] Robineau planned similar deals with the other small refiners, and the other refiners were very responsive to Robineau's proposal and felt that the 100-octane project would be of great benefit to every one involved.

Wyoming’s other senator, Democrat Harold H. Schwartz, reported in April 1942 that Wyoming refiners were working together on plans to solve the 100-octane fuel shortages. He told the Wyoming Labor Journal that all Wyoming oil refiners would benefit from aviation fuel production. The Journal added that a plant was proposed for Glenrock.[8]

Robineau concluded that the oil produced from the Lance Creek field in Niobrara County was of sufficiently high quality that it would be ideal for making 100-octane fuel. In addition, it could be shipped easily from Lance Creek to the Frontier facility in Cheyenne. But A.W. Peake, vice president of Standard Oil of Indiana, reported to National Petroleum Coordinator Harold Ickes that Wyoming did not have sufficient crude oil to supply a 6,000-barrel-per-day aviation fuel plant.

Peake's motive, in Robineau's view, was to keep the Lance Creek oil flowing to Sugar Creek, Mo., where it was being processed in Standard's own refinery.[9] Robineau wrote to O'Mahoney and pointed out that the federal government would save money if the Lance Creek oil were processed into aviation fuel at Cheyenne instead of down the pipeline in Missouri. The Ohio and Continental Oil companies, the largest producers in the Lance Creek field at the time, were willing to cooperate in the 100-octane venture, he noted. He hoped the senator could influence Standard to be similarly pliant.[10]

As it turned out, Robineau was not the only oilman in Wyoming interested in constructing an aviation fuel plant. Republican John McIntyre, Wyoming’s lone congressman, told a reporter on May 1 that Texaco, Continental and Standard Oil had sent a proposal to Petroleum Coordinator Ickes to construct a 100-octane plant at Casper. McIntyre said that financing for the construction of such a plant would come from the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation, a Depression-era agency that backed local governments, banks and businesses with financing.[11]

The Cheyenne Chamber of Commerce learned of the competing proposals and believed Schwartz and McIntyre were not doing enough to help Robineau and Frontier to set up the aviation fuel plant. Schwartz, a Casper resident, responded that he was not opposed to the project. In fact, he also supported high-octane, synthetic-rubber and butane plants in Wyoming at Parco (present Sinclair), Cody or Casper. He was opposed, however, to any plan that would cut existing production levels at other major refineries simply to facilitate Frontier's plan. McIntyre replied that he would support an aviation fuel plant for any firm coming up with a feasible proposal, but he understood that existing facilities at Frontier could not be modified to produce 100-octane fuel. It would require an entirely new addition to the present refinery, he said.[12]

By the end of May 1942, despite misgivings on the parts of Schwartz and McIntyre, the Office of the Petroleum Coordinator approved plans for 100-octane plants at both Parco and Cheyenne. The plant at Parco, owned by Sinclair Oil Company, was to be supplied with crude oil from the Texaco and Standard Oil refineries in Casper and the Continental refinery in Glenrock.[13]

Frontier, on the other hand, would supply its own crude. In reality, the crude oil for Frontier was to come from four small independent refiners: Z&W, Gray and Albany Oil, all of which Robineau had already contacted; and Silver Tip Refinery of Yoder. Robineau hoped that others would sign on later as the four independents alone would not be capable of supplying Frontier's needs.[14]

Meanwhile, O’Mahoney urged the Office of the Petroleum Coordinator to negotiate in Robineau’s behalf with Standard Oil.[15] On June 13, 1942, Howard Marshall, OPC chief counsel, told O’Mahoney that after extended negotiation with Peake, Standard was willing to sell Frontier 1,500 to 2,000 barrels of Salt Creek oil per day for the 100-octane project.[16] Standard would supply the oil for $1.12 per barrel plus a 2½ -cent-per-barrel marketing charge. Peake added, however, that it was his hope that Frontier would be able to secure oil from other sources in the Rocky Mountain area as Standard was already having trouble filling its existing contracts.[17]

Robineau and other Wyoming oil producers were concerned about oil pricing. Pipelines, operated by the major oil companies, moved the oil cheaply and avoided the otherwise high costs of shipping Wyoming oil. The average price refiners had to pay for delivered mid-continent oil was 70 cents per barrel. Companies with pipelines could pay the average in-Wyoming price of just 42 cents a barrel, send it by pipeline to their mid-continent refineries and make a big profit.[18]

At the same time, oil producers in Wyoming argued that the royalties assessed for production on government lands made Wyoming oil noncompetitive. Under the old system, producers paid a royalty to the government ranging from 12½ to 32 percent on oil taken from public lands. The more oil that was produced, the higher the percentage. At the request of independents, O’Mahoney introduced a bill to put a ceiling on government royalties at 12 ½ percent. The measure passed on Dec. 24, 1942.[19]

In June 1942, meanwhile, the Frontier project had hit another snag. Robineau was informed that the War Production Board would not give the project the highest priority rating. The board had rated all projects as to their importance to the war effort and concluded that while the project was important, it was not top priority. Without the priority rating, Frontier would be unable to secure the services of an engineering firm to design the plant before September. With construction likely to take 10 to 12 months, completion would come some time in the fall of 1943. Any project not competed by June 1, 1943, however, risked cancellation.[20]

Perhaps at the urging of Sen. O’Mahoney, the War Production Board did give Frontier the go-ahead on the project in June. The $4 million plant was to be built on 40 acres next to the existing Frontier Refinery and be completed no later than May 1, 1943.[21]

O’Mahoney took part in the groundbreaking ceremonies for the new plant in late August 1942. The plant would contribute to the war effort and also the local economy. It was estimated that construction would require 325 men, and payroll from the completed plant would add approximately $900 per day to the Cheyenne area economy. The aviation fuel would be sold exclusively to the military for the duration of the war; however, according to the local newspaper, 100-octane gasoline would still have a market after the war because carmakers were designing engines that would use it.[22]

With the plant under construction, Robineau still worried about a dependable source of crude oil. He wrote O'Mahoney saying that if Wyoming's independent refiners like Frontier were to stay in business, contracts allowing the shipment of Wyoming oil out of the state would have to be broken or new reserves would have to be discovered by independent companies that would sell to independent refiners. He pointed, once again, to the Lance Creek and Salt Creek oil shipments to out-of-state refiners, which made it impossible for local refineries to run at full capacity.[23] Robineau told O’Mahoney that even though Standard had agreed to sell oil to Frontier, corporate officials were refusing to do so. He said he believed Standard had several million barrels of oil stored at its Clayton tank farm, near Glenrock, Wyo., and again asked the senator to intervene.[24]

A month later, Robineau reported that Peake had agreed that Standard would sell Frontier enough oil to maintain its operations at a minimum capacity. He thanked O’Mahoney for his help, adding that his company had signed a contract with Continental to begin supplying oil to Frontier in December.[25]

Meanwhile, with the oil supply problems solved for the existing Frontier facility, Robineau was faced with a critical housing shortage for the workers building the 100-octane plant. The Cheyenne population had shot up from 23,000 people in 1940 to an estimated 34,000 in October 1942. Many of the new residents were affiliated with Fort Warren, which was evolving into a large quartermaster-training center. The housing shortage had become so acute that many of the workers connected to a United Airlines project underway in the capital city had to be bused in from Greeley or Fort Collins, Colo., each day.[26]

Robineau discovered 29 houses for sale at the Lance Creek oil field 150 miles north of Cheyenne. Dawson-Corbett Trucking offered to move them all to Cheyenne and set them on foundations for a total of $14,000. Installing water and sewer hook-ups, building the foundations, redecorating and modest landscaping would add $65,000 to the overall cost. At $2,240 each, the houses would be a bargain compared to the cost of building new ones. By comparison, the 55 houses already under construction in Cheyenne, and another 165 proposed houses ranged in price from $3,500 to $5,200 each. Nonetheless, Robineau needed loans from the Defense Plant Corporation because he had only $10,000 to apply toward the cost of the housing project.[27]

Confident that he would receive financing for the housing project, Robineau obtained a 60-day option on three city blocks near the Frontier Refinery. A city sewer and a Cheyenne Light and Power line ran down the alleys, and a city water line ran down the street in front of the properties. Robineau asked the Defense Plant Corporation to move quickly on his loan request, because the owner of the three city blocks, F. E. Warren Mercantile Company, would likely raise the asking price of $3,250 per block—already up from an initial asking price of of $1,000—after the 60-day option had expired.[28]

Robineau faced yet another obstacle. The 100-octane plant would require significant additional water, which he requested from the City of Cheyenne. The city council referred the request to the Mayor's Advisory Water Board in the fall of 1942 and in November, the board gave its approval, but with several limitations. The city agreed to furnish the 1 million gallons per day, but the city water, the board said, would be regarded as only complementary to Frontier’s own supply. Further, the board stipulated that Frontier pay the cost of the water line which, upon completion, would become the property of the city. Board members emphasized that the offer was not a guarantee to supply water because they could not predict snowfall or spring runoff, essential to the city’s water needs. Further, once minimum domestic requirements of the city were met, Fort Warren and the Union Pacific Railroad were next in priority for the water.[29]

Meanwhile, plant construction continued ahead of schedule even though delays could occur if steel and piping were not delivered on time.[30] The Office of the Petroleum Coordinator was responsible for seeing that those items were delivered. Robineau feared that the War Production Board would give priority in scarce building materials to two 100-octane plants under construction in California because the completion dates for both had been targeted for three months ahead of Frontier’s. The California plants had enjoyed the three-month head start in construction, Robineau pointed out, but Frontier had caught up by November 1942 because of “superior construction abilities.”[31] With O’Mahoney’s help, Robineau got the War Production Board to give all three plants the same priority.

At this point, Robineau had worked out an agreement with Socony-Vacuum Oil Company to process its oil from the Horse Creek field 25 miles north of Cheyenne. Robineau hoped the field would be a substantial enough one that Frontier could build a pipeline from it to the refinery, making Cheyenne the center of oil activity in the Rockies.[32]

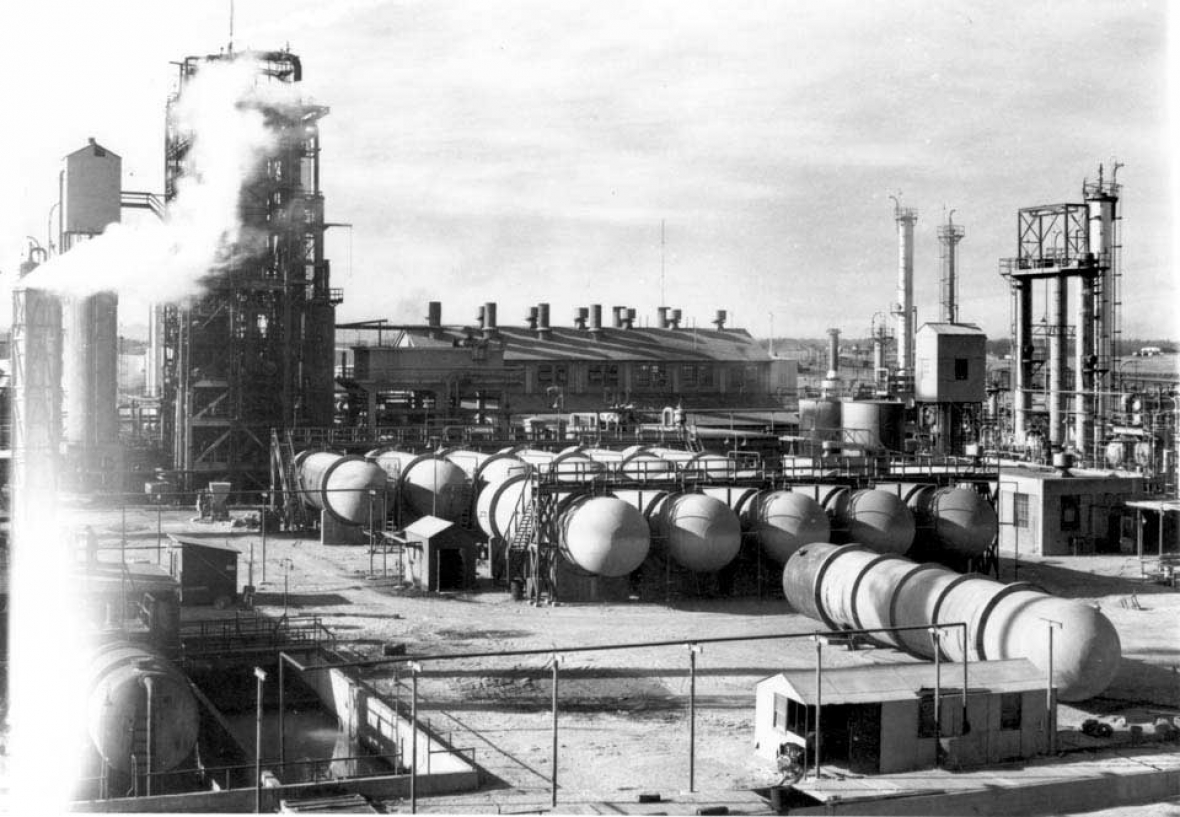

Throughout the spring, construction continued on schedule but by July 1943, the Wyoming Eagle reported that construction costs had risen to $5 million from the $4 million originally estimated.[33] Reasons for delay have not surfaced, but the plant was not completed until April 1944, almost seven months after Robineau’s September target date. Meanwhile, the construction costs had risen to $8 million, double the original estimate. The plant was finally dedicated on April 14, 1944, and began processing aviation fuel that same day.[34] The local press called it one of “Cheyenne’s greatest industries,”[35] but for the remainder of the war, the government did not release information about it. It was designated “a secret project.”36

The plant continued processing aviation fuel after the war. In December 1945, its workers negotiated a new contract with Frontier.[36] While peacetime demands continued for the fuel, the plant had made its contribution to the war effort. None of this would have been possible, however, without the help of O’Mahoney. As Robineau often acknowledged, the intervention of Wyoming’s senator at critical times caused the plant to be built. With the added factor of Robineau’s persistence, the independent refiner both profited from the war effort and contributed to the critical fuel supply necessary to win the war. Cheyenne and the rest of Wyoming gained as well. The plant added a substantial payroll to Cheyenne’s economy, which added to the city’s growth and development during the war years and beyond.

Editor's Note: We extend special thanks to the University of Wyoming’s School of Energy Resources for support for this and other articles in an ongoing series on the history of Wyoming’s energy and extraction businesses.

Notes

[1] Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 383.

[2] Ibid., p. 377. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Interior Secretary Harold Ickes to the additional position of Petroleum Coordinator in May 1941, the day after the president declared an “unlimited national emergency” even though the country had not yet entered the war. See Yergin, 377-388, for a summary of the wartime operations of the oil industry in coordination with government.

[3] Wyoming Labor Journal, Jan. 30, 1942. The Labor Journal offered the opinion that such a plant would be built in Casper, the state’s hub for oil refining.

[4] M.H. Robineau to Joseph C. O'Mahoney, Feb. 9, 1942, O'Mahoney papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

[5] T.A. Larson, History of Wyoming (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978), 497.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Duff Gray to O'Mahoney, Feb. 10, 1942, O’Mahoney papers.

[8] Wyoming Labor Journal, April 10, 1942.

[9] Robineau to O'Mahoney, April 21, 1942.

[10] Robineau to O'Mahoney, April 30, 1942.

[11] Wyoming Labor Journal, May 1, 1942.

[12] Wyoming Eagle, May 8, 1942.

[13] Rep. McIntyre made the official announcement. It was reported in the Wyoming Eagle, May 27, 1942; Wyoming Labor Journal, May 29, 1942.

[14] Robineau to O'Mahoney, June 1, 1942.

[15] O'Mahoney to Robineau June 13, 1942.

[16] Marshall to O'Mahoney, June 12, 1942.

[17] Peake to Marshall, June 8, 1942.

[18] Robineau to O’Mahoney, Aug. 30, 1942. His concerns were echoed by Glenn Nielson of Husky Refining Company, Cody. Nielson to O’Mahoney, Sept. 23, 1942.

[19] Senate Bill 1706, O’Mahoney papers.

[20] Robineau to Marshall, June 14, 1942; Robineau to O'Mahoney, June 15, 1942. O'Mahoney papers.

[21] Wyoming Labor Journal, June 26, 1942.

[22] Wyoming Eagle, Aug. 27, 1942. "Motor Cars After the War To Use 100-Octane," National Petroleum News 34, no.7 (Feb. 18, 1942) 20. Robineau also urged O’Mahoney to oppose the House Ways and Means Committee’s revenue bill, which would raise the corporate surtax rate and the excess profits tax. Robineau asserted that when he purchased Frontier Refining in 1940, he had borrowed $175,000 for improvements. If the bill passed, he would be left with only $6,175 per year for operating capital before payments to stockholders. He believed that if the law passed, Frontier would go bankrupt. Robineau to O’Mahoney, July 17, 1942.

[23] Robineau to O'Mahoney, Aug. 30, 1942.

[24] Robineau to O’Mahoney, Sept. 16, 1942.

[25] Robineau to O’Mahoney, Oct. 13, 1942.

[26] Werner O. Entemann, Defense Plant Corporation, to O.B. Smart, Division Engineer, Defense Plant Corporation. O’Mahoney papers.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Robineau to Entemann, Nov.18, 1942.

[29] Advisory Water Board to Mayor and Commissioners of Cheyenne, Nov. 10, 1942, O’Mahoney papers.

[30] Robineau to O'Mahoney, Nov. 18, 1942.

[31] Robineau to O’Mahoney, Nov. 18, 1942.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Wyoming Eagle, July 27, 1943.

[34] Wyoming Labor Journal, April 16, 1943

[35] Wyoming Labor Journal, June 25, 1943

[36] Wyoming Labor Journal, Dec. 28, 1945.

Resources

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming, 2nd ed., rev. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1978, 497.

- Mackey, Mike. “Cheyenne’s 100-Octane Plant.” in Readings in Wyoming History, 4th edition, edited by Phil Roberts, 125-131. Laramie, Wyo.: Skyline West Press, 2004.

- “Motor Cars After the War to Use 100-Octane,” National Petroleum News 34, no. 7 (Feb. 18, 1942), 20.

- O’Mahoney, Joseph C. Papers, 1866-1963. Collection 00275, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- Wyoming Eagle 1942, 1943.

- Wyoming Labor Journal, 1942, 1943, 1945.

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 383.

For Further Reading and Research

- The Joseph C. O’Mahoney papers and much more information about Laramie and Wyoming during the years that O’Mahoney was such an important part of state and national politics may be viewed on request in the reading room at the American Heritage Center in Laramie. See the field-trip suggestion below for more on the AHC.

Illustrations

- The photos of the 100-octane refinery and of Robineau and O’Mahoney shaking hands are from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The portraits of Robineau and O’Mahoney are from the American Heritage Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Robineau’s high-octane billboard is from an online site for antiques and collectibles enthusiasts, Santa Fe Trading Post. Used with thanks.