- Home

- Encyclopedia

- A Treaty In His Lens: Alexander Gardner Photogr...

A Treaty in his Lens: Alexander Gardner Photographs Fort Laramie, 1868

In the spring of 1868, Cheyenne residents crowded into James McDaniel’s Museum. This saloon offered food and drink to paying customers who were attracted and entertained by free displays of stuffed creatures, paintings and photographs. Customers could view more than 1,500 stereo photographs through patented viewers that made the pictures seem three-dimensional. Many offered a visual tour of the recently concluded Civil War. Little did patrons know that the creator of many of these already familiar images was then passing through town on his way to Fort Laramie. There, he would take photographs of people gathering to negotiate an Indian treaty. The event and its images remain significant today.

Image

The negotiations were one part of a series of treaties intended to move tribes onto reservations and make their cultures self-supporting, “which,” Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman stated, “will lead to their ultimate civilization.” Lands the tribes relinquished would be open to exploitation by emigrants and entrepreneurs. President Andrew Johnson appointed civilian and military commissioners to conduct the negotiations. Both sides hoped for a conclusion of hostilities. The strategy included authorization to close the Bozeman Trail to Montana and to abandon Forts C. F. Smith, Phil Kearny and Reno along the route.

The photographer

Born, raised and educated in Scotland, Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) originally worked as a jeweler, businessman and newspaper publisher. He promoted worker rights, pursued interests in science and, early on, became devoted to the relatively new science and art of photography. He also helped to organize, and supported relatives in, the establishment of a cooperative community in eastern Iowa. He may have met the famed American photographer Matthew Brady as early as 1851 at London’s Crystal Palace Exposition. Moving to New York City in 1856, Gardner became manager of Brady’s photographic gallery and, beginning in 1858, operated a new Washington, D. C., gallery. Gardner’s business acumen contributed significantly to Brady’s commercial success—making portraits of the social, political and entertainment notables of the times.

The Civil War broke out in spring 1861. Late that year, Gardner won an appointment to the staff of Union Gen. George McClellan and stopped managing Brady’s gallery. Drawing together a corps of photographers and sometimes working for the Secret Service, Gardner and his crew documented the war in depth; he profited from the sale of thousands of photographic prints.

Assuming the title of “Photographer to the Army of the Potomac,” Gardner recorded the horrors of Cedar Mountain, Antietam, Gettysburg and many other campaigns and battles. His images revealed the worst—bloody battlefields, dead soldiers and devastated landscapes. Portraits of Union generals and politicians provide an unmatched record of war-time leadership. Gardner photographed Abraham Lincoln at least 37 times. After the assassination, Gardner followed with a pictorial record of the Lincoln conspirators and their executions.

He had opened his own gallery in mid-1863 and thousands of his photographs were produced as large, imperial-sized prints and pocket-sized carte de visites. His stereo views provided entertainment in private homes and at social gatherings. Gardner concluded his war-time accomplishments by publishing the most iconic images in the monumental, two-volume Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War.

It was the war images that transfixed the gaze of the nation—including patrons at McDaniel’s Museum in Cheyenne. The West was next to offer the inexhaustible Gardner with new opportunities—to photograph railroads, soldiers, Native Americans and booming towns.

Across the continent

Beginning in 1867, Gardner began documenting an anticipated 35th parallel route for the Union Pacific Railway, Eastern Division. With goals to cross from Kansas to the Pacific Ocean, the survey anticipated a more southern route over the mountains of Colorado and across New Mexico, Arizona and California. Gardner joined the survey in Colorado, crossing into New Mexico. In September 1867 he returned east to follow the railroad back across Kansas to Hays City before returning to tasks in New Mexico and then reaching the Pacific Ocean in February of the next year. The ultimate result of this work was publication of stereo photographs and Across the Continent, an album of images documenting the route.

Image

Scenes in the Indian country

The project set a precedent for extensive photography created during later government surveys led by Clarence King, Ferdinand Hayden and John Wesley Powell, with Timothy O’Sullivan and William H. Jackson among those operating cameras across the landscape. Shortly after completing Across the Continent, Gardner hit the road again. Hired to serve as official photographer for Indian treaty negotiations at Fort Laramie, he was about to produce many of his most enduring images of the West.

Image

As Gardner packed to prepare for travel to Fort Laramie, he decided his basic needs were a large-format camera for creating negatives for big prints, and a smaller camera designed to take the closely parallel exposures of two-inch images for stereo photographs. He filled crates and boxes with heavy glass plates to hold the emulsion for negatives. Other boxes contained chemicals for processing them. Gardner also had to find room for tripods, lenses and other gear along with his clothing and supplies for personal needs.

When he arrived by train at Omaha, Nebraska, on April 14, a secretary for the treaty commission supplied him with a gallon of whiskey. Nine days later, the Union Pacific delivered him to Cheyenne. Traveling north overland with two of the commissioners, Gen. Sherman and the civilian Samuel Tappan, Gardner arrived at Fort Laramie six days later. They were too late for the first meeting between other commissioners and Oglala and Brule Sioux. On April 29th, the day of their arrival, Brule leaders Spotted Tail, Red Leaf and Swift Bear were among those to first sign the treaty.

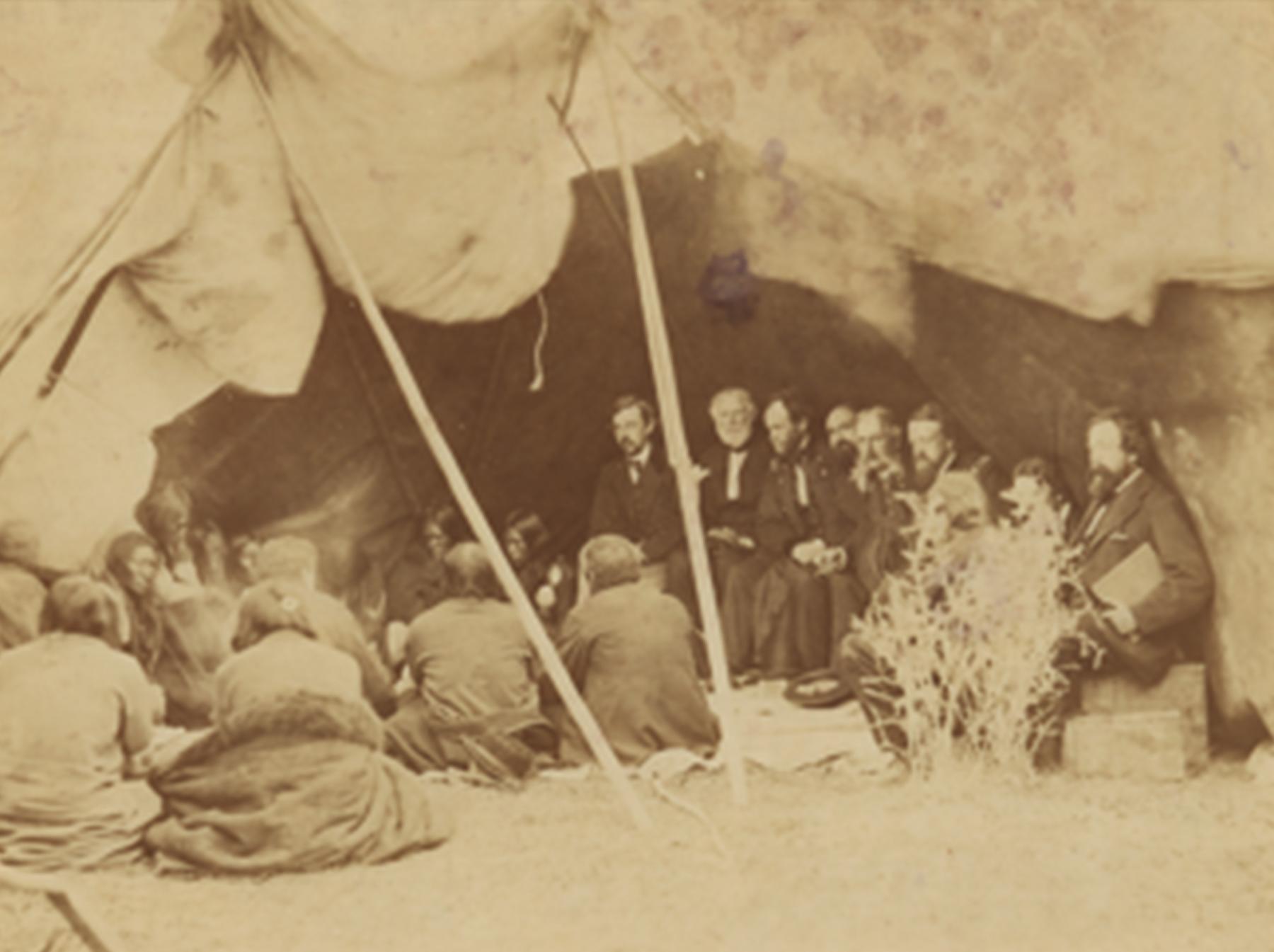

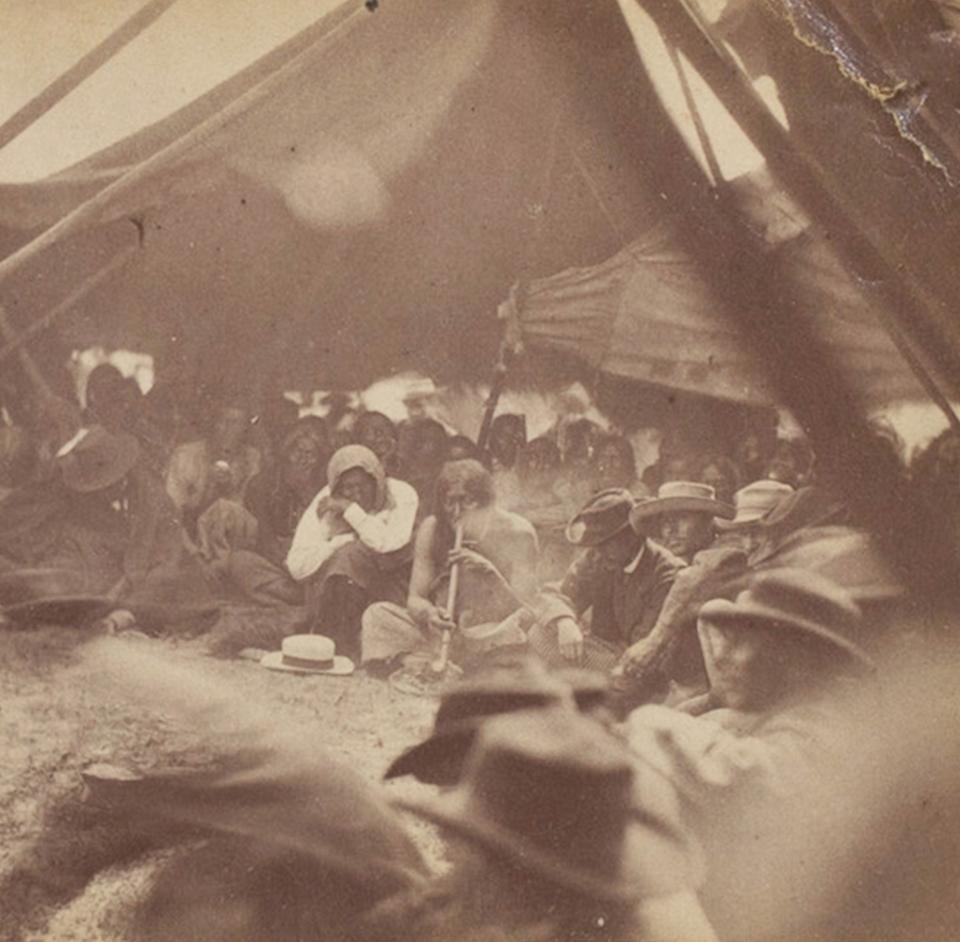

Gardner proceeded to take views of daily life in the Sioux encampments, including images of Spotted Tail and other chiefs. Within a few days, delegations of Crow, Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho people arrived at the fort. Eleven leaders signed the treaty on May 10. For several days, Gardner took advantage of opportunities to record the distribution of gifts, the slaughtering of cattle, and daily life in the Crow, Cheyenne and Arapaho camps. Images show details of dress and equipment, women cooking and sewing tipis and children playing.

During May, Gardner, despite bulky camera equipment and complicated processes, created an enduring record of Fort Laramie itself. Significant views show the area landscape, the river ferry, bridge, distant views of buildings and the post sutler’s elegant quarters. Across the Laramie River he photographed Brown’s Hotel, likely enjoying this saloon’s whiskey and maybe other offerings. Soldiers are shown on parade at the fort and officers of the 4th U. S. Infantry are portrayed standing outside the iconic two-story porch of Old Bedlam, which remains today.

Gardner created significant records of other notable residents of Fort Laramie. Many mountaineers and traders served as witnesses and translators for the treaty negotiations and images of their mixed-race families are among the photos Gardner took on the fort grounds. John Richard, Leo Palladay, Charles Gereau, James Bordeaux, Amos Bettelyoun, William Bullock and others are present, but unfortunately are not clearly identified in most of the images.

Image

Image

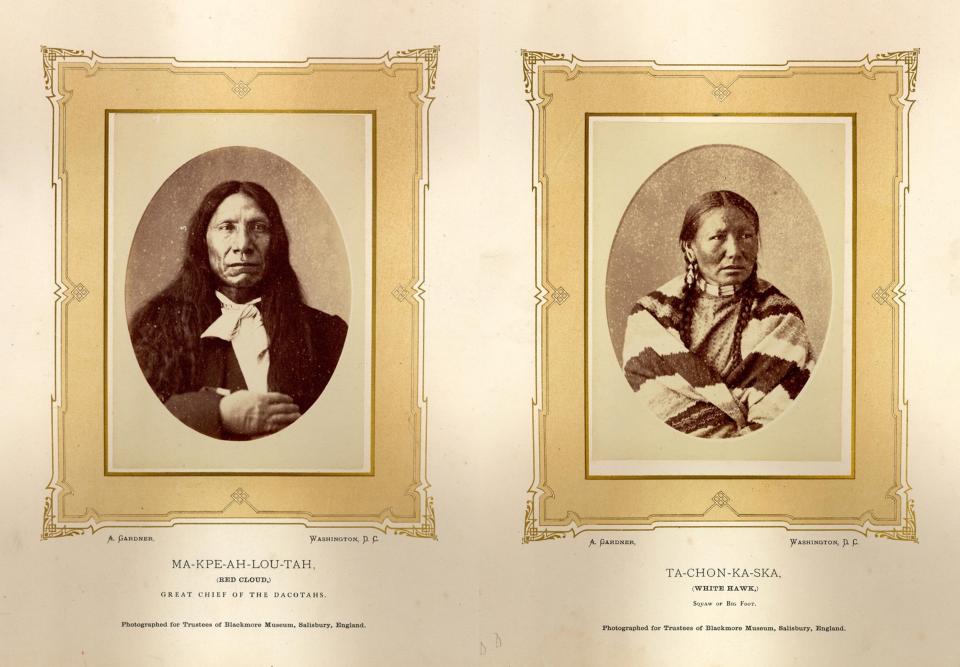

The treaty

On May 24th the commission met with the Oglalas. Man Afraid of His Horses along with 70 lodges had arrived on the 21st, but Red Cloud refused to attend with his people. Negotiations proceeded and ultimately 36 additional men signed the treaty. The Minicoujous under Lone Horn arrived on the 28th and 17 men signed the treaty. A group photograph shows Spotted Tail, Roman Nose, Lone Horn, Man Afraid and others. Government agents distributed traditional presents after each session and left a copy of the treaty for Red Cloud’s signature in case he came in later.

Red Cloud finally arrived at Fort Laramie in November with a large number of Oglalas and Brules. He came because the Bozeman Trail and posts in the Powder River Basin had finally been abandoned as he had insisted. He now signed the treaty.

The treaty recognized the Lakota as a sovereign nation and established the Black Hills as part of their reservation. With the Indian agencies moving to the new reservations, no longer would the Fort Laramie area be a frequent residence for the Sioux and other tribes. Many of the frontiersmen with Native wives and children also moved away. The pictures taken by Alexander Gardner, therefore, stand as a reminder of their collective presence, experiences and contributions.

As historian Martha A. Sandweiss astutely notes, “families found themselves riven by violence, people struggled to define and defend their rights, and the federal government sought new ways to flex its power.” And the treaty as it was ratified by the Senate was different from what the tribes thought they had agreed to. In years to follow, strife continued and the government and intruders frequently violated the treaty. Not until 1980 did the United States Supreme Court confirm the government’s obligation to compensate the Lakota for the taking of tribal land. Today, the treaty still faces court challenges and is a living document of Native Peoples’ continuing struggle.

Gardner and some of the commissioners left Fort Laramie in late May, headed for Cheyenne. Along the way, he photographed a variety of scenes along Chugwater Creek and spent enough time at Fort D.A. Russell outside Cheyenne to create an overall shot of officers’ quarters at the post. Upon returning to his home and studio in Washington, Alexander Gardner evaluated about 200 glass negatives. He also created sets of 8” x 10” prints on large cardboard mounts for distribution to the commissioners. He benefited from sales to the public and, as with earlier surveys, offered sets of stereo views for sale.

Image

Portraiture of Native peoples

Gardner’s images of Native leaders at Fort Laramie were not his first. Even during the Civil War, diplomatic visits to Washington, D.C. brought many tribal representatives to the capital; often they ended up standing in front of Alexander Gardner’s camera.

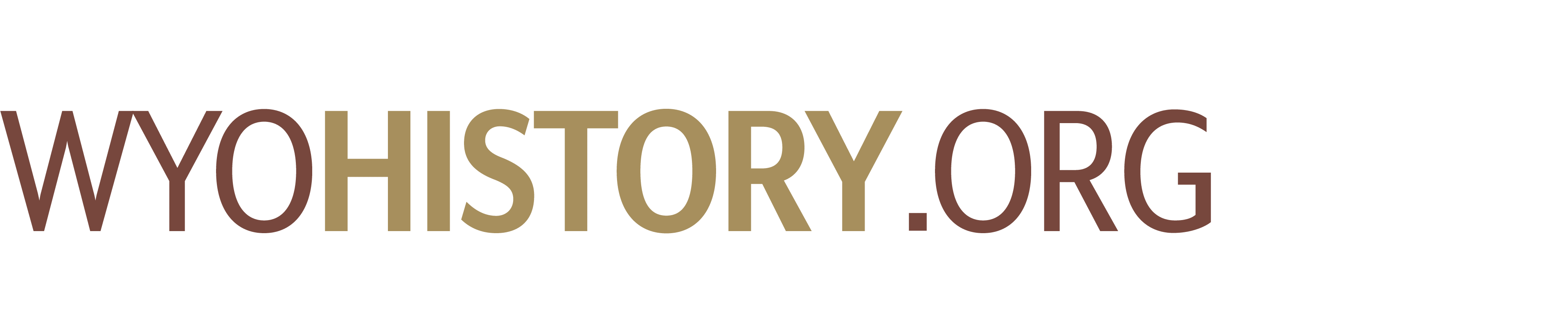

In 1872, English collector William Henry Blackmore contracted with Gardner to create formal portraits of visiting Indian dignitaries. This was part of his effort to create a detailed photographic record of Native peoples. Ten albums with 240 images from 19 tribes resulted. Blackmore’s own museum in England published the images and he exhibited many of them at the Smithsonian Institution. The negatives, at the time under the control of F.V. Hayden’s United States Geological Survey of the Territories, were combined with the work of William H. Jackson and others. Jackson himself cataloged the collection in 1874 and 1877. It was through this effort that among the 1872 portraits, Gardner created images of Sioux women and fifteen Lakota Sioux leaders including Big Foot, White Hawk, Stabber, High Wolf and, finally, Red Cloud. Of his several Red Cloud portraits at this time, one shows him with Gardner’s patron, William Blackmore. The British Museum eventually acquired the photographs that were initially owned by Blackmore’s museum.

The Fort Laramie Treaty photographs taken by Alexander Gardner in 1868 are in part a visual census of the place and the diverse peoples at the scene. As a pictorial document they tell us of Crow, Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho people at the time. In their company are soldiers, commissioners, commission staff, interpreters, mixed-race families, traders, clerks, laborers and one photographer. They record an event of lasting importance that was—briefly—a triumph for the tribes. On the 150th anniversary of the treaty, thousands of Native peoples gathered at Fort Laramie to embrace the living importance of a treaty still very much a part of their lives.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support that in part made this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- United States Department of the Interior, Government Printing Office. Miscellaneous Publications no. 5 (first edition only), 1894. Jackson, William Henry. Descriptive Catalogue of the Photographs of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories for the Years 1869 to 1873 Inclusive. Washington, D.C., 1874, accessed May 8, 2023 at https://pubs.usgs.gov/unnumbered/70038995/report.pdf.

- _______________________________________________________. Miscellaneous Publications no. 9, 1877. Jackson, William Henry. Descriptive Catalogue of Photographs of North American Indians. Washington, D.C., 1877, accessed May 8, 2023 at https://pubs.usgs.gov/unnumbered/70039633/report.pdf.

- United States Government, National Archives. Fort Laramie Treaty, 1868. For transcribed text, and description, for the treaty signed on April 29, 1868. between the U. S. Government and the Sioux Nation, see: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/fort-laramie-treaty. For digital images of the treaty, see: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/299803.

- Wyoming Digital Newspaper Collection, accessed April 4, 2023:

- The Cheyenne Leader 01, no. 18, Oct. 31, 1867

- The Cheyenne Leader 01, no. 201, May 13, 1868

- The Cheyenne Leader 01, no. 178, April 16, 1868

- The Frontier Index, May 5, 1868

Secondary Sources

- Aspinwall, Jane L. Alexander Gardner: The Western Photographs, 1867-1868. Kansas City, Missouri: Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, 2014.

- Demallie, Raymond J. “’Scenes in the Indian Country’: A Portfolio of Alexander Gardner's Stereographic Views of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty Council.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 31, no. 3 (Summer 1981): 42-59.

- Fleming, Paula Richardson and Judith Luskey. The North American Indians. New York: Harper & Row, 1986.

- Jaspersen, Andi. “Cheyenne’s Greatest Showman.” Visit Cheyenne, Dec. 17, 2020, accessed March 9, 2023 at https://www.cheyenne.org/blog/post/cheyennes-greatest-showman/.

- Katz, Mark. Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner, The Civil War, Lincoln, and the West. New York: Viking Press, 1991.

- Rea, Tom. “Peace, War, Land and a Funeral: The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.” WyoHistory.org, Nov. 8, 2014, accessed Oct. 13, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/peace-war-land-and-funeral-fort-laramie-treaty-1868.

- Sandweiss, Martha A. “Seeing History: Thinking about and with Photographs.” Western Historical Quarterly 51, issue 1 (Spring 2020): 1-28, accessed Oct. 13, 2023 at https://academic.oup.com/whq/article-abstract/51/1/1/5678758.

- _________________. ”Still Picture, Moving Stories, Reconstruction Comes to Indian Country.” Civil War Wests. Testing the Limits of the United States. Edited by Adam Arenson and Andrew R. Graybill. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015, 158-178.

Where to view more Alexander Gardner photos online:

- British Museum collections including a selection of the 1872 Washington portraits and a number of the treaty images from the Blackmore Collection. Accessed Oct. 13, 2023 at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=Alexander&keyword=Gardner.

- U.S. Government Peace Commission with the Indians: An Inventory of Its Photographs at the Minnesota Historical Society. 89 images including some portraits and large selection of the oversize images. Note that a few images are unrelated and of later period. http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/sv000194.xml Accessed March 16, 2023.

- The Newberry Library, Digital Collections. Collection of General C. C. Augur. Commissioner set of images including both portraits done in 1872 and Fort Laramie large-size images. https://collections.newberry.org/CS.aspx?VP3=DamView&VBID=2KXJA42OO00B&SMLS=1&RW=1600&RH=767#/DamView&VBID=2KXJA42OO11D&PN=1&WS=SearchResults. Accessed March 16, 2023.

- William T. Sherman, commissioner collection of Alexander Gardner photographs, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian. Accessed Oct. 13, 2023, at https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/sova-nmai-ac-077

- William Harney, commissioner collection of Alexander Gardner photographs, Missouri Historical Society. Accessed Oct. 13, 2023, at https://mohistory.org/collections?text=Scenes%20in%20the%20Indian%20Country&type=Photograph&images=0.

- Alexander Gardner Collection. Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. Accessed Oct. 13, 2023, at https://art.nelson-atkins.org/people/10308/alexander-gardner/objects.

- Alexander Gardner Collection focused on Kansas Pacific images. Kansas Historical Society. https://www.kansasmemory.org/locate.php?query=Alexander+Gardner

- Digital scans at Princeton of W. H. Jackson’s Indian photos, including those by Gardner. In the Princeton Collection, search by “Alexander Gardner” and “Laramie.” Accessed Oct. 13, 2023 at https://dpul.princeton.edu/pudl0017/browse/the-william-henry-jackson-photographs-of-north-american-indians-collection.

Illustrations

- Alexander Gardner’s self-portrait in a mountain-man outfit is from the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Used with thanks.

- The Gardner portraits of Red Cloud and White Horse Owner are from the Blackmore Collection at the British Museum. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Man Afraid of His Horses smoking in the treaty tent is from the Christopher C. Augur collection of photographs of the western United States 1846-1889 at the Newberry Library. Used with permission and thanks.

- The rest of the photos are from the archives at the National Museum of the American Indian, used with permission and thanks.