- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Tribes Sell Off More Land: The 1905 Agreement

The Tribes Sell Off More Land: The 1905 Agreement

At the turn of the last century, the fortunes of the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes on the Shoshone Reservation in central Wyoming were reaching a low ebb. Poverty was widespread, hunger was routine, disease was constant and the populations of both tribes had fallen to their lowest level ever.[1]

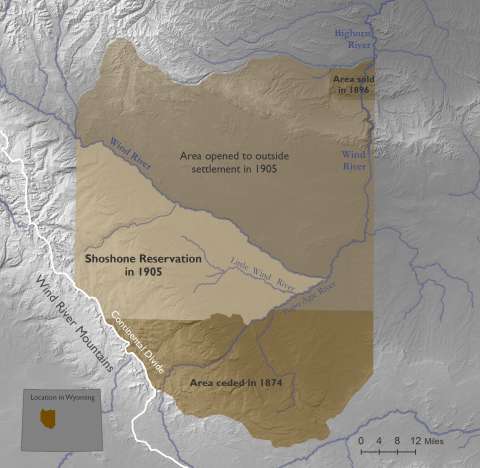

Pressure on them to sell their lands had been steadily increasing for decades. The Shoshone had ceded the southern third of their reservation on Wind River in 1874, just a few years after it was established. In 1896 both tribes agreed to the sale of the Big Horn hot springs at what’s now Thermopolis, Wyo., for $60,000.

The loss of these two portions left a reservation of around 2.3 million acres, roughly bisected from northwest to southeast by the Big Wind River. Land south of the river was well watered by the many creeks and small rivers flowing off the Wind River Mountains, and most of the Indian people lived there. Land north of the river was much drier and used mostly for grazing. A great many of the animals that grazed it were owned by local white ranchers who didn’t pay for the privilege, or only recently had begun paying very low grazing fees to the tribes.[2]

At the same time, annual payments of food and supplies guaranteed to both tribes were about to stop coming. The Shoshone had signed the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868 and the Arapaho had signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Both treaties promised the tribes that signed them annuities for 30 years; the payments continued a few years longer as part of the tribes’ agreement to sell the hot springs in 1896.

A new plan

In the first years of the 20th century, government officials of the U.S. Indian Bureau approached the tribes with a plan. If the tribes agreed to sell the land north of the river, they would receive up-front cash payments, followed by future revenues that would pay for a new irrigation system for their lands south of the river, along with livestock, schools and water rights for the new irrigation system.

The government would finance the plan by turning development of a large irrigation project north of the river over to a private company. That project would theoretically attract settlers who would buy the recently ceded land. Revenue to the government from the land sales would then go to the tribal people as promised—and the whole arrangement could be worked out without any funds from the U.S. Treasury.

This was a plan with a lot of pieces. Not all, in the long run, would fall into place.

Washakie, longtime chief of the Eastern Shoshone and a very old man, died in 1900. Among the Arapaho, longtime chiefs Black Coal died in 1893 and Sharp Nose in 1901. Still at this time, the Arapaho had no formal, legal status for their presence on Wind River.

The treaty the Arapaho had signed in 1868 promised them a reservation of their own, but with no place specified for it; After ten years on the move, they were escorted to the Shoshone Reservation by the U.S. Army in an arrangement everyone had assumed to be temporary.

It’s probably fair to say that the Shoshone continued to resent Arapaho presence on the reservation, and that for their part, the Arapaho were uncertain about whether and to what extent they could count on the government to support their presence on Wind River.

But as time went on, government superintendents on Wind River continued to call meetings of leaders of both tribes together when it came time to discuss rations, land cessions, leases and more--as though both tribes had equal status. And now, with the old chiefs having died, there were new leaders in both tribes.

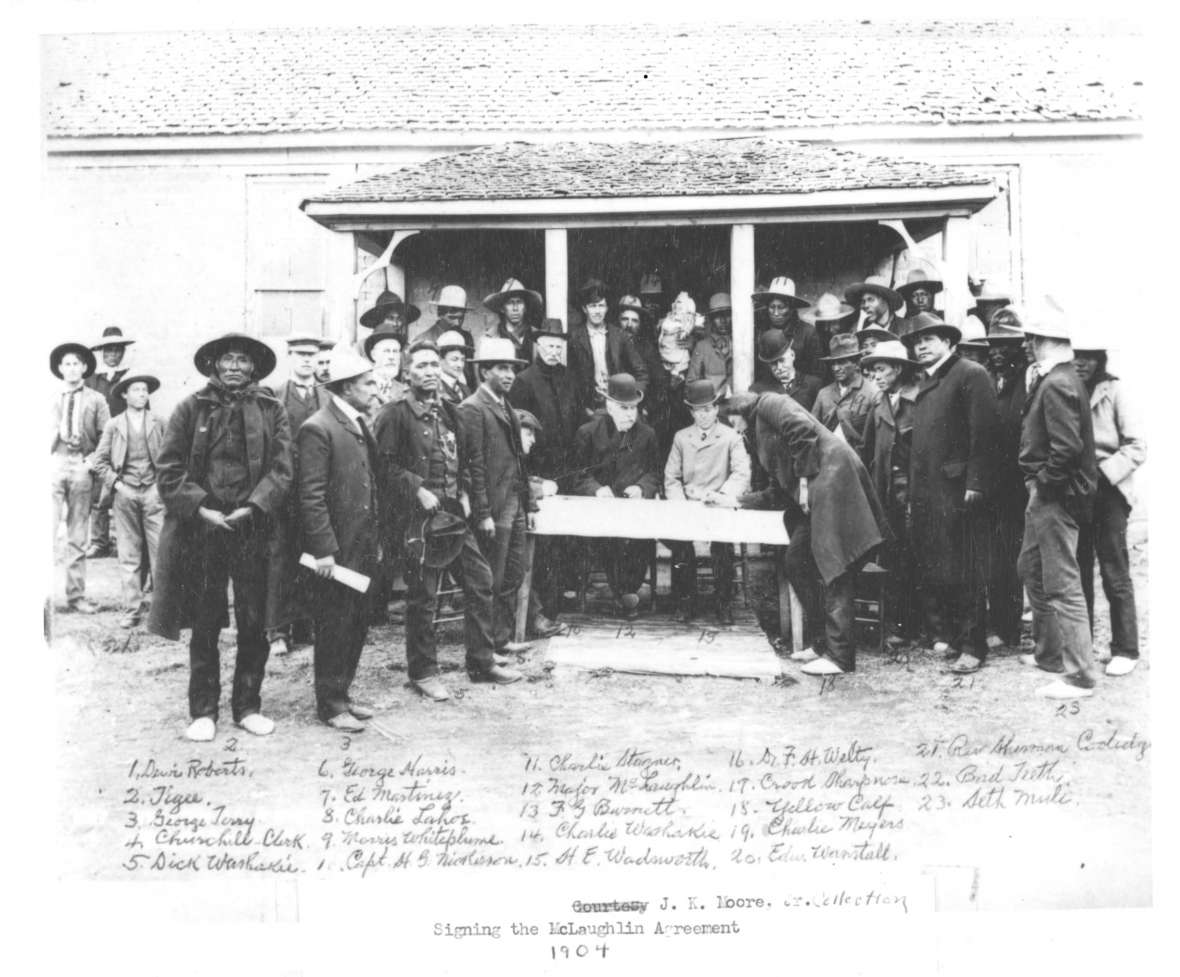

In April 1904, James McLaughlin, the government negotiator with long experience among the Sioux who had negotiated the hot springs sale in 1896, returned to Wind River with the new government proposal. He urged the tribes, meeting jointly, to cede nearly 1.5 million acres of land, that is, about 2,300 square miles, north of Big Wind River. This would still leave them more than 800,000 acres south of the river, and should, the government officials said, bring them revenues of more than $2.2 million—around $62.5 million in 2018 dollars. In the long run, the tribes may only have gotten as much as $500,000—around $14.2 million today.[3]

A vote

|

Many of the tribal people felt they needed money more than they needed the land, and many of the leaders were ready to sign. One, however, held out. Lone Bear was now head council chief of the Northern Arapaho. He said the land was worth twice what McLaughlin was offering. Yellow Calf, not yet an Arapaho council chief, suggested some changes. Sherman Coolidge, a Northern Arapaho who had been raised by whites and educated in the East, and who had become an Episcopal priest and returned to the reservation as a missionary, spoke in favor of McLaughlin’s proposal.

But longtime Fremont County historian, former Riverton Museum Director Loren Jost suggests that the biggest issue during the negotiation was the right of the Arapaho to even be involved. “It was a point of contention in every negotiation with the government leading up to the 1904 meetings,” Jost writes. “The Shoshones had a legally legitimate basis for their objections to the involvement of the Arapahos, but the government was always unwilling to take it into account. Based on the totality of events leading up to the 1904 meetings, it seems likely there was a great deal of animosity underlying the discussions and the voting.”

During negotiations, Lone Bear’s wife fell ill and he left; many Arapaho left with him. In the end, McLaughlin obtained signatures on the agreement from 202 of 247 eligible Shoshone men but only 80 of 237 Arapaho men—a majority of all the men on the reservation. But this was only a small minority of the Arapahos. [4]

Jost also suspects that because the Shoshone occupied lands further south from the river and closer to the foothills of the Wind River Mountains, and thus farther away from the lands north of the river to be ceded, they would have been more likely to approve the agreement. The Arapaho, who lived closer to the lands to be opened to white settlement, had more to lose—and thus most of them, Jost suggests, voted against the proposal. [5]

Terms of the 1905 agreement

Under steady pressure from Wyoming’s lone U.S. congressman, Frank Mondell, Congress amended, then approved the agreement on March 3, 1905.[6] Among its provisions were the following:

- The tribes ceded all the land north of the Wind River down to the mouth of the Popo Agie River, as well as the southeast corner of the reservation—from the mouth of the north fork of the Popo Agie to the reservation’s southern boundary.

- Individual tribal members who, thanks to the allotment system made possible by the Dawes Act, owned land on the ceded portions would be paid for it. The government would buy that land at $1.25 per acre in amounts up to 640 acres. In addition, the government would pay all Arapaho and Shoshone people $50 each—per capita—as soon as possible or within 60 days after the rest of the ceded lands were opened for sale to white homesteaders.

- Money from government leases on ceded portions would also go to the tribes.

- Using the revenue from the homesteaders who purchased the lands, the federal government would secure state of Wyoming water rights for the tribes—so that Indian lands south of the river could be legally irrigated under Wyoming law.

- Land for homesteading was to be sold to whites for $1.50 per acre if it sold in the first two years, $1.25 if it sold in the next three, $1 per acre if it sold in the three years after that, and after eight years the land would be sold to the highest bidder.

- From these revenues, the government, according to the agreement, would reimburse itself $85,000 for the per capita payments, $35,000 to cover the cost of surveying the ceded lands and $25,000 to start work on irrigation ditches for tribal lands south of the river. Revenue after that would flow to tribal accounts, from which the Indian Bureau would spend up to $50,000 for livestock and up to $50,000 for schools. Remaining funds could be spent on rations, if needed.

- There would be a public accounting every July, and the spending levels could be renegotiated after 10 years.[7]

Some objections

Lone Bear sent a message to Washington on March 6: “We think treaty ratified by Congress not agree with original treaty signed by tribe.” By “treaty” he was referring to the recent agreement; his point was that changes had been made in what he thought he had agreed to. Near the end of the next year, tribal elders protested that they still had not received any per capita payments nor any revenue from the sale of part of the ceded lands that had been sold as town lots in the new town of Riverton. Town lots would naturally go for much higher prices per acre than agricultural homesteads.

When the per capita payments finally did come, the Indian Bureau withheld from many families the payments for children, apparently as a way to restrict the amount of cash flowing to families. Indians were too “indolent and imprudent,” bureau officials declared, to manage their own affairs. Per capita payments for the children would finally be approved in 1909.[8]

Homesteading on the ceded lands

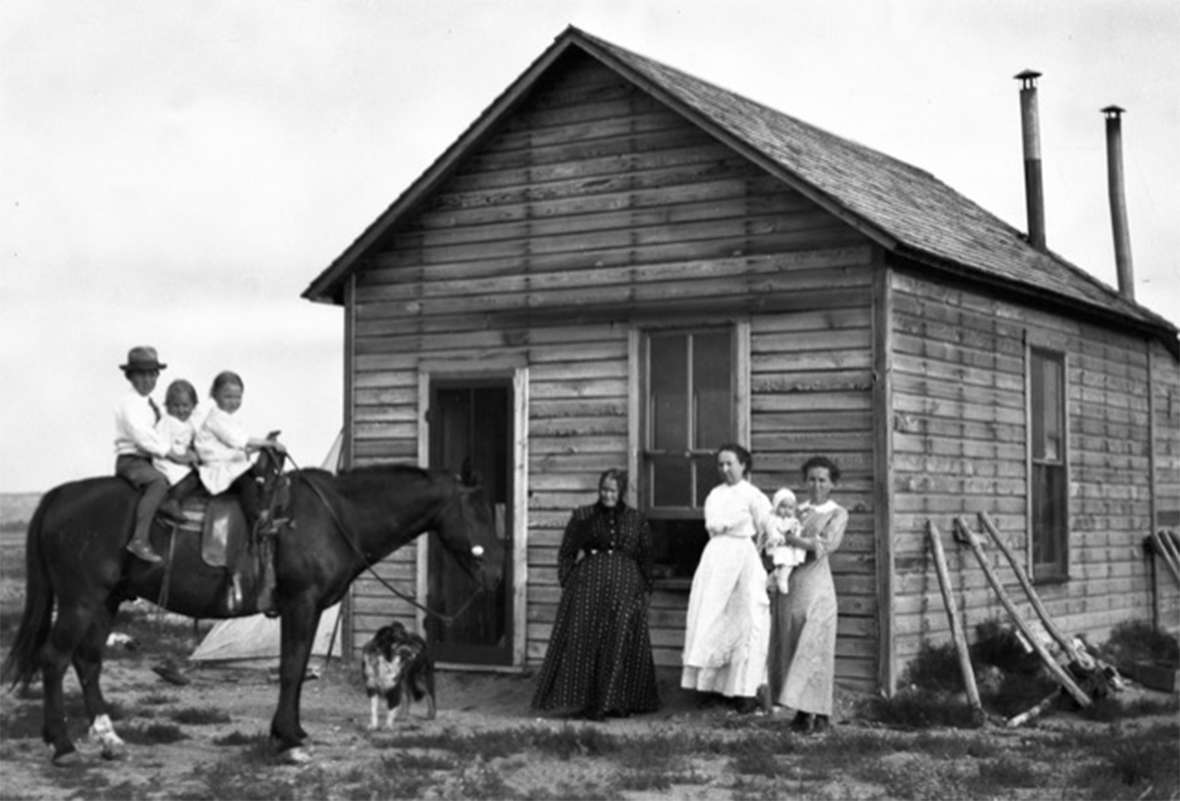

Ceded lands, in accordance with the agreement, were thrown open for homesteading the year after the tribes signed the document. That same year, 1906, the Chicago & North Western Railroad reached Lander, Wyo. from Casper. On the edges of the Shoshone Reservation, the towns of Shoshoni, Riverton and Hudson had been founded in 1905 and 1906. Families with high hopes began pouring in to homestead the supposedly soon-to-be-irrigated land north of the river.

An irrigation project of 300,000 acres was originally planned. Homesteaders were attracted by low prices of $1.50 per acre. The state of Wyoming, which owns the water under Wyoming law, awarded the contract for the first two canals to a new company, the Wyoming Central Irrigation Company. The company offered water to the farmers for a fee, with plans to use those fees to continue building the irrigation system. The farmers balked, wanting to wait to pay fees until water was actually available to them. Lawsuits followed. Most of the original homesteaders simply left.[9]

Low revenues, new fees

Under the 1905 congressional act, proceeds from land sales north of the river were to go to the tribes partly to finance irrigation on newly allotted lands south of the river. When the sales of the ceded lands produced much less than the projected revenue, the tribes did not receive the expected amount of payment for those lands, nor did they receive the promised cattle or the ditches and water rights they had been expecting.[10]

Even so, the Indian people were charged irrigation fees whether or not they used the new ditches, as government officials by this time were hoping to recoup from the Indians the losses the government faced as a result of the sluggish land sales.

That is, instead of reimbursing the tribes for lands they’d already given up, the government charged the allottees for bringing water to their plots—before the water ever arrived.

If the Indians could not pay the fees, officials pressed them to sell the land. White speculators, seeing possible opportunity in the situation, advertised for buyers in eastern cities. Many allottees sold their lands for a fraction of their worth.[11]

Government rescue for the irrigation project

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation finally stepped in to rescue the irrigation project late in the 19-teens—long after the tribes had given up their ownership of those lands. Diversion Dam on the Big Wind River was built in 1923, a power-generating reservoir in 1926, and a canal was begun around that time to carry water toward the lands north of the river.

The Wyoming Central Irrigation Company, meanwhile, failed completely by 1928 and the USBR took over the entire project; only 16 settlers had stuck it out that long. But the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression brought more—mostly farmers from the Midwest. The last homesteads were parceled out by lottery in the 1940s to veterans of World War II. And the Shoshone and Arapaho people got next to nothing from the deal.[12]

Editors’ Note: This and other 2018 and 2019 articles and digital toolkits for classroom use on the history of tribal people in Wyoming are possible with support from scholars and educators on the Wind River Indian Reservation, the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, the Wyoming Council for the Humanities and several Wyoming school districts, including districts headquartered in Fort Washakie, Arapahoe, Shoshoni, Lander, Powell , Laramie, Douglas and Afton, Wyoming. WyoHistory.org extends its thanks to all.

Resources

- “1896 Big Horn Hot Springs Land Cession Agreement …” Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. Accessed Dec. 8, 2017, http://jacksonholehistory.org/wp-content/uploads/1896-cession.pdf.

- Flynn, Janet. Tribal Government: Wind River Reservation. 1991. Reprint, Lander, Wyo.: Mortimore Publishing, 2008. An extremely useful look at the history of government and leadership on the Wind River Reservation, with clear details on the treaties, agreements and lawsuits.

- Fowler, Loretta. Arapaho Politics, 1851-1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1982, 93-96, 129-131. An excellent ethnohistory of the Northern Arapaho people, with emphasis on their constantly evolving leadership and governance structures over time.

- Jost, Loren. Email to WyoHistory.org Editor Tom Rea, Jan. 9, 2019.

- O’Gara, Geoffrey. What You See in Clear Water. New York: Knopf, 2000.

- Rea, Tom. “Peace, War, Land and a Funeral: The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.” WyoHistory.org. Accessed Dec. 8, 2017 at /encyclopedia/peace-war-land-and-funeral-fort-laramie-treaty-1868. Article takes the funeral of Mni-Akuwin, Spotted Tail’s daughter, as a place to begin telling the story of Lakota-white relationships surrounding the1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

- Stamm, Henry E. IV. People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825-1900. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. A useful, reliable source on the Eastern Shoshones of the 19thcentury, with emphasis too on their relations with their white and Arapaho neighbors.

- _________________. “Land Cession of 1904,” in “Wind River Treaty Documents. Treaties and Agreements Between the Eastern Shoshones and the United States.” Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. Accessed Dec. 10, 2018 at http://jacksonholehistory.org/wind-river-treaty-documents/.

- .“Wind River Reservation, 1900-1920s.” An Introduction to Wind River Reservation. Accessed Dec. 3, 2017, at http://jacksonholehistory.org/an-introduction-to-the-wind-river-indian-reservation-of-wyoming/.

- “Wind River Treaty Documents. Treaties and Agreements Between the Eastern Shoshones and the United States.” Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum website on the Wind River Reservation. Includes commentary about and links to full texts of the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, plus the 1872 Brunot cession, the 1896 Big Horn Hot Springs cession and the Land cession of 1905. Accessed Dec. 12, 2017, at http://jacksonholehistory.org/wind-river-treaty-documents/.

- WyoHistory.org. “Coming to Wind River: the Eastern Shoshone Treaties of 1863 and 1868,” accessed Nov. 23, 2018 at /encyclopedia/coming-wind-river-eastern-shoshone-treaties-1863-and-1868.

- _____________. “The Arapaho Arrive: Two Nations on One Reservation.” Accessed Nov. 23, 2018 at/encyclopedia/arapaho-arrive-two-nations-one-reservation.

- ______________. “When the Tribes Sold the Hot Springs,” Accessed Dec. 9, 2018 at /encyclopedia/when-tribes-sold-hot-springs.

Other Maps

- Shoshone Reservation boundaries described in the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1863: /sites/default/files/shoshonemapnew_0.jpg

- Shoshone Reservation boundaries described in the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868: /sites/default/files/twotreaties7.jpg

Illustrations

- The photos of t Indian agent James McLaughlin and Episcopal Priest Sherman Coolidge are from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photos of Lone Bear, Yellow Calf and the railroad yard are from a collection of Joseph Dixon photos made on the Shoshone Reservation in 1913 and acquired in 2018 by the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum in Casper. Used with permission and thanks.

- The map of the reservation showing the Shoshone Reservation boundaries after the 1905 land cession is by Margo Berendsen of the Wyoming Geographic Information Science Centerat the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the signing ceremony in 1904 is originally from the American Heritage Center via the website of the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum, where the image is #388 in the "Wind River Treaty Councils and Signings" section of the website's Wind River Photo Gallery. Used with permission and thanks. In addition to the people named in the caption above, others in the photo include at front left in long coat and large dark hat, hands clasped, longtime Shoshone leader Tigee. Standing front of the post and behind McLaughlin’s left shoulder, in dark hat and white mustache is early South Pass City pioneer and, later, Lander-based businessman and rancher H.G. Nickerson. Nickerson served as Indian agent from 1898 to 1902 but was not reappointed as he stirred up so much strife, especially among the Arapaho. Next to McLaughlin, in light-colored coat and derby hat, is Fincelius “Fin” Burnett, who served in Army campaigns in the Powder River country in the 1860s and came to the reservation in the early 1870s as reservation farmer and Indian bureau employee. Front right in buttoned black overcoat and dark hat, the Rev. Sherman Coolidge, an Arapaho raised by whites in the East who came back to the reservation as an Episcopal priest and was an ally of Nickerson in these years.

- The 1912 photo of the Holmberg family on their homestead is from the Riverton Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

[1] Geoffrey O’Gara, What You See in Clear Water, (New York: Knopf, 2000), 38, gives figures of 841 Eastern Shoshone and 801 Northern Arapaho at around this time, but does not give an exact date.

[2] Loretta Fowler, Arapaho Politics, 1851-1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority. (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press), 1982, 91-92.

[3] Fowler, 93; O’Gara, 31, revenue figures 39; inflation calculations from http://www.in2013dollars.com.

[4] Fowler, 93-95.

[5] Loren Jost, email to WyoHistory.org Editor Tom Rea, Jan. 9, 2019.

[6] Frank Mondell, Unpublished Autobiography, vol. II, Collection 1050, Box 1, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, 308-314. Wyoming Congressman Mondell gives a detailed account of his legislative maneuverings to persuade the U.S. House of Representatives to pass the bill ratifying the 1905 agreement.

[7] Fowler, 95; Janet Flynn, Tribal Government: Wind River Reservation. 1991. (Reprint, Lander, Wyo.: Mortimore Publishing), 2008, 34; O’Gara, 39;

[7] Fowler, including Lone Bear’s message, 96.

[9] Fowler, 130.

[10] Fowler, 130.

[11] Fowler, 130-131; O’Gara 40-41.

[12] Henry Stamm IV, People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825-1900,(Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 243; Stamm, “Land Cession of 1904,” in “Wind River Treaty Documents. Treaties and Agreements Between the Eastern Shoshones and the United States.” Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. Accessed Dec. 10, 2018 at http://jacksonholehistory.org/wind-river-treaty-documents/ ; O’Gara 31-32; Loren Jost email, Jan. 9, 2019.