- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Order Out of Chaos: Elwood Mead and Wyoming’s W...

Order out of Chaos: Elwood Mead and Wyoming’s Water Law

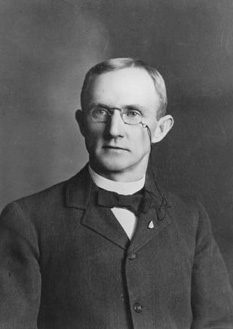

In the years leading up to statehood, Wyoming’s systems for putting its water to use were a unique, disorderly mess. Elwood Mead, who wrote most of the state’s water law at age 32, quickly became the chief agent in the drive to pull order out of chaos.

Wyoming had become a territory in 1869, in the aftermath of the Civil War. Most of its early leaders were veterans of that war, as were most of its early male citizens. After the tribes were driven onto reservations in the late 1870s, these white newcomers saw the chance here to start fresh and make something new — new lives and new profits.

They went at it with a will, and water was not left out of their designs. Pretty quickly they borrowed ideas about water and water rights from California and Colorado, places transformed by gold rushes years before people chose to settle Wyoming. In California and Colorado, gold miners came up with a system under which people could take water from a stream, first-come first-serve, and move it where they needed it. The system was called “prior appropriation.” It meant just that: a kind of squatter’s right — you reach out and appropriate something for yourself, prior to anyone else doing it. Then, the idea goes, you’ve got a right to it better than the right of anyone who comes along later.

“First in time, first in right,” is the shorthand for prior appropriation in water. It was a system for places where water was scarce, so it made sense in Wyoming as well.

In Wyoming’s early years, all that was required to reach out and appropriate the water you saw in a stream was to post a sign on a nearby tree, saying “I hereby claim this water and here’s how much of it I claim.” Later, the Territorial Legislature decided it might be good to get some record of those claims, so people had to go file them in the county courthouse. That could mean someplace 50 or 150 miles or more away — not often a handy place for someone else to go check before they wanted to get water out of that same stream.

In 1888, Elwood Mead, age 30, having been hired as territorial engineer to figure out the water rights situation, surveyed what was on the books in the county courthouses.

“The virtue of self-denial had not been conspicuous” among the early settlers, Mead remembered later.

That is, it was not uncommon to see someone claiming more water than actually flowed in a stream. People who came here were enthusiastic, ambitious … imaginative. They had big ideas.

In one case, someone claimed from one stream more water than actually flowed in the entire state of Wyoming, and proposed to divert that water with a ditch two feet wide and six inches deep. When people started arguing over conflicting claims, and some fights moved from the creek-bank into court, the territorial courts (whose judges didn’t know much about water) often wound up allocating water by the amount stated on paper in the claim, or perhaps by the size of the ditch.

No matter that that meant more water per acre for one irrigator than for his neighbor just downstream. Wyoming Territory was rife with excess water claims, covering much more water than people were using or could use — generating conflict, wasting time, money and energy, and providing ample opportunity for speculators.

The final straw was the famous drought-plus-hard-winter of 1886-1887 that busted Wyoming's open-range stock industry. The stockmen who survived financially decided it might be a good idea to secure their claims to watering holes, and grow some hay in summer to tide the herds over the winter.

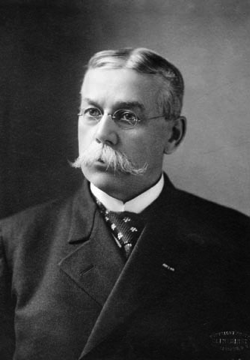

Some started to think about irrigated agriculture as a new endeavor that might be a little more stable than their industry. Stockman and businessman Francis E. Warren had already, along with Joseph Carey, started an irrigation venture, the Wyoming Development Company, at the site that is now Wheatland. (Both were former territorial governors; both would later become state governors and U.S. senators.) Now they wanted a water-law system that would confirm their own water claims and build a basis for new irrigation development.

So much for chaos. Next: How to bring order to this scene?

Warren helped recruit Mead as the first territorial engineer, charged with drafting new water laws. Territorial Governor Thomas Moonlight offered the job to Mead sight unseen in March 1888; after he met Mead, he declared: “You have been on my conscience ever since I first saw you this morning. I had no idea you were so young. If I had known this I would never have offered you the place, and the reason is that if you come here I am sure you will fail.” Moonlight warned against men like Warren dominating Wyoming politics. But Mead liked Warren, and Warren liked Mead. Warren often declared, though, that when Mead came to Cheyenne, he “was still wearing pinafores.”

Elwood Mead grew up on a southern Indiana farm on the Ohio River, where the main problem with water was getting rid of it. He loved the life of a farming community, and later resented the speculators, the moneymen who after the Civil War had bought up land and, in his view, turned independent farmers into poor tenants. Mead spent his first years out of engineering school along the Front Range in Colorado, learning about irrigation and water fights. He read about water battles that had gone on in California.

Mead thought people could do a better job handling Western water, and thereby build communities. Real communities were scarce in Wyoming. Most of the few towns were cowboy watering holes by old forts, or ports of call for railroad crews along the Union Pacific lines. Mead saw water management as a way to change that.

Like the reformers of the oncoming nationwide Progressive movement, Mead believed that with experts managing water as a resource to support communities, it should be possible to strike a balance between private and public interests. Mead wanted to see the resource put in the hands of private individuals, with continuing oversight by the public through their government. He wanted to achieve both the stability that would encourage private investment, and the flexibility that could adapt to change.

State ownership, and an expert board

Mead proposed two key elements new to water law in Wyoming and the West. With the help of Warren and others, he got them written into the new constitution.

First, he insisted on the idea of active state ownership of water. Many a western constitution talks blandly of how the water belongs to the state. Mead, however, pumped life into that empty language by establishing that no one here could acquire rights to use water without a permit from the state. The state’s engineering staff would approve or deny an application, based on its practical and financial likelihood of success, and its accord with the public interest in water use.

Second, Mead set up an expert board, instead of a court, to decide water disputes and to establish, change or eliminate water rights. The Board of Control was the State Engineer and the superintendents of each of the state’s four main hydrologic basins — the watersheds of the North Platte, Green-Snake-and-Bear, Wind/Bighorn, and Powder rivers. The superintendents were people who knew water and to whom irrigators could bring issues without the expense of a lawyer.

“(I)n Wyoming, at least, there will no longer be the ludicrous spectacle of learned judges solemnly decreeing the rights to from two to ten times the amount of water flowing in the streams,” said one admiring observer.

The state’s permit system and the board of control were to operate on one key principle: Water rights were tied to actual use, not to a paper claim describing what someone simply hoped to use.

Thus the state could allocate water in response to actual needs — and defend against speculators, whom Mead saw as the worst threat to development of stable communities in frontier Wyoming. Mead adopted the “use it or lose it” rule of traditional Western water law, under which non-use for several years meant the water right could be lost. Further, permits would have time requirements for getting water put to use. And finally, old territorial claims and new state permits would be subject to “adjudication”— review of use by superintendents and challenge by neighbors — so that a final certificate for a water right might cover only water actually used.

Mead wanted to encourage both good-faith investment and new ideas: if your plan for diverting and using water didn’t work, you should lose the water right and its priority so someone else with a better idea could come in, get a permit, and put that water to work. If your plan did work, you got a right to keep using the water — and you had to keep using it, to keep the right.

Both the water users and the state had property rights in water — users could put the water on their crops; the Board of Control could decide whether the water could move to a new place or a new use. This was the crux of the private-public balance, the combination of stability and response to change that Mead sought.

An early success on Clear Creek

The new water law itself was radical change — as was freely admitted by its supporters in the Constitutional Convention, who successfully pushed the language Mead drafted. Tying water rights to actual use often meant restricting people to use of about 10 percent of the water they had claimed under the old system.

The new system was vindicated dramatically, however, where it was most likely to be defeated: in Buffalo, in Johnson County. Johnson County had voted against the new constitution in 1890. Apparently, people there didn’t trust anything coming out of Cheyenne. Apparently justifying those suspicions, a force of cattle ranchers and their hired Texans invaded Johnson County just two years after statehood to kill men they had decided were cattle thieves. Many of Mead’s backers were among the invaders or their supporters.

Meanwhile Mead’s office, through his superintendent, had started an adjudication of Clear Creek, which runs through Buffalo. They were adjudicating other streams around the state at the same time. The Clear Creek adjudication had started before the invasion. However, Mead’s water superintendent for the Powder River area, W.J. Clarke, joined the invaders — and it appears that at some point he lost the records he had gathered for the Clear Creek adjudication.

But Mead persevered. Shrewdly, he managed to appoint a popular hero, Edward Gillette, as the new superintendent in time to get the Clear Creek adjudication done. Gillette was identified with the Burlington Railroad and anti-Invasion politicians. He adjudicated Clear Creek rights, and the result was the typical 90 percent cutbacks in water claims on the creek. A Colorado investment company that had acquired a number of Buffalo area properties by foreclosure filed a lawsuit challenging the adjudication results. The Wyoming Supreme Court ruled to uphold Mead's new system.

More important, however, was the fact that the limited rights certified by the new superintendent meant that everyone on Clear Creek made it successfully through a drought year. At that point, the irrigators realized they supported the new system after all.

A social engineer

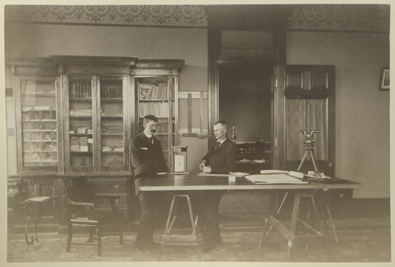

Mead’s system was soon heralded nationwide as the model for Western water law, and he got a job in 1899 in Washington, D.C., heading a new division of Irrigation Investigations for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. There he headed meticulous research efforts into comparative water-law systems, irrigation and crop experiments, and produced a number of reports consumed by people involved in irrigation work across the West.

In 1907 Mead got what for him was an experience almost as formative as his time in Wyoming: he was invited to direct work on large-scale water development in Australia.

In his eight years there Mead got involved not only in water management and projects, but the fostering and care of irrigation communities. That, it seems, won his heart and the core of his energies for the rest of his life. Returning to the U.S. in 1915, a year after war broke out in Europe, Mead gave speeches to national groups of engineers and of social reformers, and he began to call himself a “social engineer.” He pushed for an American version of the Australian system for government disposition of irrigated land in small plots in "irrigation colonies," with government aid in construction of houses, grading and seeding of land, low interest loans for improvements, and other assistance.

“Such an organization in the United States would doubtless be called Socialism gone mad,” Mead wrote,

and the same sentiment has occasionally been heard here [in Australia], but fears regarding the outcome have been largely allayed by the successful results of past experience in other lines of development. Undoubtedly leaving settlers to contend unaided with every obstacle, as was formerly done in the United States, has created men of great enterprise, initiative and hardy mental fiber, and there is some danger that the State by doing so much may weaken the individual strength of its citizens. Nevertheless, after two years’ study of the results obtained here [in Australia], I cannot but regret that more was not done in America for the pioneer in the arid American States. I feel sure that the hardship which many families underwent might have been entirely averted with no loss to the public but with a very material gain to the nation in the rapidity and character of the development.

|

Water management remained at the center of his social engineering vision. He got an appointment with the University of California at Berkeley as Professor of Rural Institutions, and began working with California officials to promote new irrigation communities there along Australian lines. A government farm loan system was one of his proposals. It would create solid rural communities: the best place, he believed, to grow citizens. Mead got two such communities built in California, but in the 1920s, as agricultural prices crashed after the boom days of the war, the inhabitants of one of his model towns “lynched” the oil portrait of Mead in their community hall.

Federal support for irrigation

Meanwhile Mead had also been a close observer and critic of the federal Reclamation Service, established in 1902 to build irrigation projects across the American West. Mead, and the Wyoming delegation led by Warren, had in the 1890s increasingly supported federal involvement in big water projects, as they saw private and state-aided projects fail for lack of deep pockets. Wyoming got two of the early Reclamation projects – the Shoshone (later renamed Buffalo Bill) and Pathfinder dams. But a decade later, frustrations had set in even for the agency that could call on the federal purse. The projects had proved expensive and were not bringing in the revenue to repay costs that their promoters had projected. Irrigators under the projects were unhappy with the debts they had to take on, and with federal policies pushing for repayment. Mead called for more Reclamation emphasis on social needs.

In 1924, Reclamation’s chief critic got the chance to head up the agency and see what he could do. As Chief of what was now called the Bureau of Reclamation, Mead went to work. He proposed financial reforms. He proposed a moratorium on construction of all new projects until the social needs on existing projects (from farm loans, to agricultural extension work and cultural centers) were met. He proposed new projects in the rural South to reclaim swamp lands.

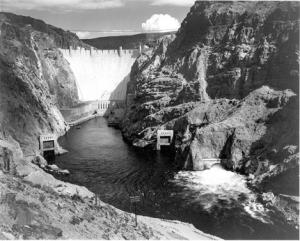

And he guided construction of the massive Boulder (Hoover) Dam on the Colorado River near Las Vegas. Mead directed all of that work, and put special care into the design of Boulder City, the town for construction workers. Lake Mead, the reservoir backed up by the Hoover Dam, was named for him. The project became a flagship of all the New Deal public works aimed at putting the unemployed back to work. Young members of President Franklin Roosevelt’s brain trust found Mead, then in his early 70s, one of the exciting people in Washington, and the rural resettlement programs of the New Deal were based on his experience and advice.

All this time Mead never lost his connections to and interest in Wyoming. When he was in Australia he wrote to Wyoming protesting a Wyoming Supreme Court decision that allowed people to sell water rights off their land (the Legislature took Mead’s advice and enacted a law to override the court’s decision). When he was investigating the Reclamation Service in 1915 he hired Gillette, his former superintendent in Buffalo, to help him look into the debts of irrigators in Powell on the federal Shoshone Project. When he headed the Bureau of Reclamation he sent a young researcher in the depths of the Depression to investigate living conditions on the Willwood project near Powell.

|

In the 1920s he marshaled support from Wyoming Senators Francis Warren and John Kendrick to push (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) for more federal social and financial services on federal irrigation projects. In the 1930s, despite his concerns about poor soils, Mead authorized the Kendrick project, also known as Casper-Alcova, which built Alcova and Seminoe dams on the North Platte—as a parting jobs-creation gift to the state for retiring Wyoming Senator Kendrick.

Mead married and had three children by his first wife, who died in Wyoming in 1897. He lost his right arm in a trolley accident when returning home after a baseball game in Washington, D.C. in 1901; in 1906 he married the nurse from the amputation operation, and had three more children. He died in office in 1936, while working on the Hoover Dam.

Resources

Mead’s scrapbooks from his years in Wyoming, including newspaper clippings on items he found relevant to his work, are archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center. A 1992 biography, Turning on Water with a Shovel, by James R. Kluger, assembles all the details of Mead’s life.

But to get a sense of the intellectual passion that made Mead tick, it is far more worthwhile to read his own writing. The biennial reports of the state engineer, and the annual reports of the territorial engineer, are eloquent. They are available at the State Library in Cheyenne as well as the Water Resources Library in Laramie. The easiest access to his writing is on line on the Wyoming State Engineer’s website, http://seo.state.wy.us/PDF/FinalMeadBooklet.pdf in a selection of writing from Mead’s engineer reports to Wyoming and from his later speeches and articles on water and social engineering.

Primary sources

- Biennial Reports of the Wyoming State Engineer, 1892-1900.

- Farm Investment Co. v. Carpenter, Wyoming Supreme Court, 9 Wyo. 110, 61 p. 258 (1900).

- Kinney, C. S. A treatise on the law of irrigation: including the law of water-rights and the doctrine of appropriation of Waters, as the same are construed and applied in the states and territories of the arid and semi-humid regions of the United States; and also including the statutes of the respective states and territories, and decisions of the courts relating to those subjects. Washington, D.C.,, W.H. Lowdermilk, 1894.

- Lampen, D. A Report of an Economic Investigation of Home Conditions on Federal Reclamation Projects. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 1929.

- Mead, Elwood. Selected Writings of Elwood Mead on Water Administration in Wyoming and the West. Compiled by A. MacKinnon and J, Shields. Cheyenne, WY: Wyoming Water Association and the Wyoming State Engineer’s Office. Accessed Dec. 22, 2010 at http://seo.state.wy.us/PDF/FinalMeadBooklet.pdf.

- Mead, Elwood. Recollections of Irrigation Legislation in Wyoming, an enclosure in a letter to Grace Raymond Hebard, March 27, 1930. Mead Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. (Also reprinted in Selected Writings of Elwood Mead, cited above.)

- Pomeroy, J. N. Treatise on the law of water rights as the same is formulated and applied in the Pacific states, including the doctrine of appropriation. 1893.

- Reports of the Territorial Engineer, Wyoming, 1888-89.

- Revised Statutes of the Territory of Wyoming. Title 19: Irrigation. (1887)

- Warren, F.E., Dictation and Biographical Materials prepared for the Chronicles of the Builders, American Heritage Center archives, University of Wyoming.

- Wyoming Constitution, Article I, section 31; Article VIII, sections 1 and 3.

Secondary sources

- Conkin, Paul K. "The Vision of Elwood Mead." Agricultural History, 34, April 1960, pp. 88-97.

- Dunbar, R. G. Forging New Rights in Western Waters. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press: 1983.

- Hays, S. P. Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency; the Progressive Conservation movement 1890-1920. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press: 1959.

- Kluger, J. R. Turning on Water with a Shovel: The Career of Elwood Mead. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. University of Nebraska Press. 1978.

- MacKinnon, Anne "Historic and Future Challenges in Western Water Law: The Case of Wyoming." Wyoming Law Review, 6:2, 2006. pp. 291-330.

- Robinson, M. C. Water for the West: The Bureau of Reclamation, 1902-1977. Chicago: Public Works Historical Society. 1979.

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Brief History of the Bureau of Reclamation. 2000.

- Trelease, F. J. Cases and materials on water law. St. Paul: West Publishing Company, 1979.

- Wilkinson, Charles. F. The Eagle Bird: Mapping a New West. Boulder, CO: Johnson Books, 1999.

- Wilkinson, Charles F. "Introduction to the Culture of Water Symposium," Wyoming Law Review, 6:2, 2006.

Illustrations

- The portraits of Elwood Mead and F.E. Warren are from the Wyoming State Archives, negative numbers 2463 and 19423, respectively, and the photo of Mead in his office is from the American Heritage Center’s digital collections, negative number ah002551. The photos of the woman on the cutting machine and the man by the ditch are from the Homesteader Museum in Powell. Special thanks to all three institutions for permission to use these photos. The photos of Lake Mead and the Ansel Adams photo of Hoover Dam are from Wikipedia. The 1918 photo of Buffalo Bill Dam is from the Bureau of Reclamation’s online selection.