- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Sweetwater County, Wyoming

Sweetwater County, Wyoming

Sweetwater County, Wyoming, nearly twice the size of Connecticut and just 64 square miles smaller than Massachusetts, is marked by buttes and mesas, canyons and wide expanses of basin brush. It is Wyoming’s largest county, by area. Table Rock, Pilot Butte and the Boars Tusk are its most famous landmarks, but places like Black Rock and North and South Table Mountain are equally striking.

It is the Green River Canyon, however, that came early on to symbolize the West and its vastness. Artist Thomas Moran's “Green River Cliffs, Wyoming”, 1881, captured the essence of the landscape that is Sweetwater County. In the painting, stark cliffs in bright hues open the view to a land that stretches away west and north towards the river source. Moran shows us a place few understand but nearly all fall in awe of when they first see it.

The artist painted these cliffs on the Green several times, and always put them at the core of his composition. These are the cliffs a person sees today north of the highway when driving past Green River, Wyo. on Interstate 80. With their ever-changing colors, they reflected the angles of the sun in Moran’s paintings and served as the backdrop for open spaces. He often set American Indians in the foreground as the essential element in a world of openness and possibility.

Early history

People lived in what’s now Sweetwater County as early as 12,000 years ago. By the time Europeans arrived in the early 1800s, the Comanche and Shoshone who lived here had developed complex cultures. They lived off the land and traded valuable goods, like banded cherts for making tools. These cherts—rocks that resembled flint—were desired and traded throughout the region. Thus when the horse first arrived in the 1700s, the Indians started raising horses and trading their stock with neighboring tribes along the same routes, as far north as the Canadian Blackfoot Nation.

From their homes in present southwest Wyoming they moved north and south across the Plains, riding horses, Wider, faster travel brought them in direct contact with Spanish, French and English traders and enabled the Indians to expand their economy. The English speakers feared and respected the Shoshone; similarly, the Spanish on their northern frontier dreaded the Shoshone’s Comanche cousins. Eventually the Shoshone would return to what’s now southwest Wyoming. By the time the United States purchased Louisiana from the French in 1803, the portion of present southwestern Wyoming that the new country claimed belonged to the Shoshone.

Other tribes — the Crow, Sioux, Bannock, Ute, Arapahoe, and Blackfeet — hunted and raided in the Wyoming Basin. They could not, however, out-compete the Shoshone in their basin homeland.

The Wyoming Basin

The Wyoming Basin, a land of diversity and complexity, dominates southwestern Wyoming. The boundaries of the basin are not clearly defined. The southern boundary runs roughly along the Yampa River in Colorado and the Uinta Mountains of Utah. The boundary then runs north along the crest of the Wyoming Range, east to the Wind River Mountains, and then follows that range southeast to where it hits the Sweetwater Arch, and along this arching range of mountains to the Rawlins Uplift, just west of Rawlins.

That defines three sides of the basin; at Rawlins the boundary may be drawn south until the mountains open up at the Yampa near present day Craig, Colo. This space includes most of Wyoming’s Uinta, Lincoln and Sublette counties, and small pieces of Carbon and Fremont County, but Sweetwater County is its core.

Though the area appears to be covered primarily with grasses and sagebrush, the vegetation is varied—and edible. Prickly pear cactus, Indian rice grass, chenopodia—the flowering plants of the goosefoot family—and such plants as rose hips thrive in the region and once provided food and nutrition. The Shoshone knew how to process these plants for food and knew how to hunt the bison, deer and antelope that grazed on the grasses and brush. The tribe produced enough of these items to allow them to trade hides, furs and meat with the first explorers and trappers who passed through or settled briefly in this basin.

Exploration and fur trade

Saying which European came first to southwestern Wyoming is difficult. Two Franciscan monks, Silvestre de Escalante and Francisco Dominguez, residents of New Spain, passed by the southern edge of the Basin in 1776. They saw the Uinta Mountains from the south and heard of the Yamparika Comanche who lived to north of the mountains in present southwestern Wyoming and northwestern Colorado.

Spaniards and probably Frenchmen may have come into the region well before Robert Stuart recorded his eastbound journey through the northern Wyoming Basin and over the Continental Divide at South Pass in 1812. Stuart, however, became the traveler who made the region known to the new claimants of the land.

When fur trader William Henry Ashley came west he did not follow Stuart’s path, but traveled instead through the heart of the Red Desert. In the spring of 1825, Ashley passed through the Wyoming Basin and present Sweetwater County. He noted in March of that year that it snowed an average of two out of every three days that month.

Ashley established a trapping and trading system that dominated the Rocky Mountain fur trade for decades, adapting it from the Shoshone trade system that relied on annual rendezvous for barter and exchange. Ashley’s first rendezvous, in 1825, on the Henry’s Fork 20 miles upstream from its confluence with the Green River, was the first such gathering held by trappers in the Rocky Mountains, and was held in present Sweetwater County.

Trails west

The trappers and traders showed future travelers the way west. In 1830, Warren Ferris reported that wagons could travel over South Pass. In 1832, Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville took wagons over the pass. By the 1840s, wagon traffic over South Pass became commonplace. But the land south of the pass still belonged to Mexico, and the Oregon country, west of the pass, was claimed jointly by England and the United States. Up to the 42nd parallel, therefore, most of what’s now Sweetwater County lay in Mexico.

Two things combined to alter Sweetwater County’s future course. The first was the United States victory over Mexico in 1848, which placed the region under the U.S. flag. The second was the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California in January of that same year. By 1849 the rush was on.

In 1848, Oregon Trail historian John Unruh estimates, 400 travelers went west from the states to California. The next year, 25,000 headed for the gold fields, and in 1852, the peak year of such travel, 50,000 people made the trip. Between 1840 and the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, according to Unruh, 200,335 individuals went overland to California. He counts 53,062 who traveled to Oregon and 42,862 to the Salt Lake Valley. In those 20 years, nearly all the overland travelers over South Pass came through the northwest corner of present Sweetwater County, roughly along the route of Wyoming Highway 28, from South Pass through Farson to the Green River.

The significance of the overland migration through Sweetwater County cannot be underestimated. A system of stage lines led to the creation of stage stations, first on the route over South Pass and later along a more southern route, across the Red Desert south of present Interstate 80, then down through Bitter Creek Valley to present Rock Springs, Wyo.

To move information quickly across the continent, the Pony Express was established in 1860, and put out of business 18 months later by the transcontinental telegraph. The Pony Express and telegraph lines followed the South Pass route.

But the more southern route, the Overland Stage Road along Bitter Creek, proved to be the more direct way west. It was this southern passage that intrigued railroad investors and engineers. Not only was it the easiest, most direct and, in some years, the safest road west, the route also offered plentiful coal deposits, for fuel for the steam locomotives.

When the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 became law, the railroad companies began in earnest to look for a route west. They settled on a large part of the Overland Trail through much of what is now south central and western Wyoming. The grades were manageable and the coal was abundant. Both the Union Pacific Railroad, building west from Omaha, Neb., and the Central Pacific Railroad, building east from Sacramento, Calif., needed coal to supply their locomotives.

Mining and railroad building thus went together hand in hand. After the Civil War, sufficient manpower, energy and money were available to allow construction to begin. The transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869.

Forming a county

By 1867, meanwhile, when most of what’s now Wyoming was part of Dakota Territory, the Dakota Legislature had created two counties, Laramie, where Cheyenne was and is located, and Carter County for the western end of the territory, named for longtime Fort Bridger sutler William Alexander Carter. A Carter County government was established, more or less, at the gold camp of South Pass City near the headwaters of the Sweetwater River, where gold had recently been found and a rush was on.

In 1869, Wyoming Territory was established, with its capital in Cheyenne and its most important towns—Cheyenne, Laramie, Rawlins, Rock Springs, Green River City and Evanston—strung east to west across the territory’s southern tier along the Union Pacific line.

The new territorial legislature changed the name of Carter County to Sweetwater County, and counted 2,862 county residents in a territorial census. Like the territory’s other earliest counties—Laramie, Albany, Carbon and Uinta—Sweetwater County ran from Colorado to Montana. Rock Springs, a coal-mining town, and Green River City, a railroad town, were and are both in Sweetwater County.

By 1870, the gold diggings around South Pass were starting to play out. By 1873, territorial and Union Pacific officials were tired of making the difficult, 60-mile trip from the railroad north to South Pass City to conduct business with the Sweetwater County government. Late that year the legislature, under pressure from railroad officials, acted to declare Green River City the county seat—subject to the approval of Sweetwater County voters at the next general election the following fall.

In the spring of 1874, county officials moved the government south, to Green River City. But there were more people in the gold camps than along the railroad, and voters in September defeated the relocation. The county government moved back north.

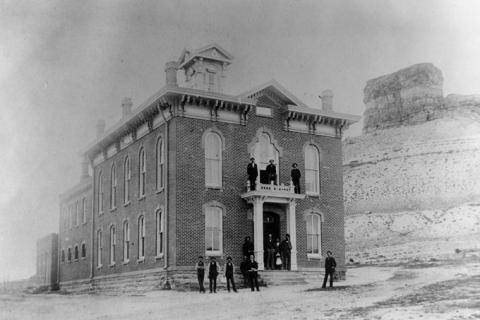

Finally, in December 1875, the Legislature declared that Green River would be the permanent county seat, and just to make sure the deal was final, declared as well that a courthouse be built in Green River for between $20,000 and $25,000, “of brick or stone and of good material.”

In 1886, the Legislature authorized the formation of Fremont County out of the northern two-thirds of Sweetwater County. This meant that the Sweetwater River and its tributaries, ironically, were no longer in Sweetwater County.

Labor strife

Meanwhile, the Union Pacific Railroad and the coal mines it owned continued to dominate life and people’s livings all across southern Wyoming Territory.

A well-worn generalization holds that the Union Pacific Railroad used Civil War veterans and Irish immigrants to lay its rails, and the Central Pacific used Chinese.

The reality was not that simple, however; many Irish also worked for the Central Pacific. When the railroad opened for traffic in May 1869, Chinese workers began doing the repair work on the newly laid tracks along both the C.P. and U.P. lines. This ultimately led to a large Chinese population living in southwestern Wyoming Territory.

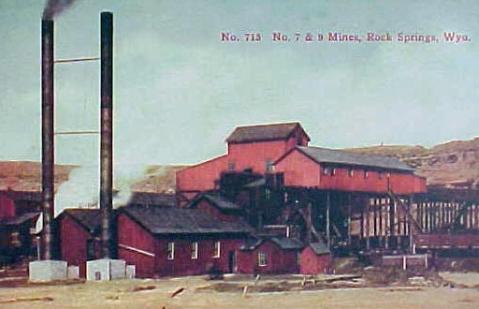

Chinese laborers first lived in railroad camps set at six-mile intervals along the line. From the Utah border to Laramie, laborers lived with other sojourners in houses built by the Union Pacific. In 1874, the company decided to try these efficient workers out in its coal mines.

By 1880, Rock Springs had the largest Chinatown in Wyoming Territory. Nearly all the residents were men. The 1880 U.S. Census lists 470 Chinese living in Sweetwater County, with 349 in Rock Springs alone. Only one female lived in this Chinatown; her name, according to the census, was Mai Wing.

The Chinese outnumbered white miners and most workdays were peaceful, but tensions due to latent prejudice and perceived preferential treatment for Chinese, and the fact that the Chinese were willing to work for lower wages, were on the rise.

On Sept. 2, 1885, a mob of miners of European descent attacked Chinatown and burned it. They killed 28 Chinese men and wounded more than a hundred others. The causes and blame for the event are still debated; some historians blame the Union Pacific Coal Company. Blame does not lessen the tragedy, however.

Workers from around the world

In any case, the event did cause the Union Pacific Coal Company to change company policies. In 1886, the company began hiring diverse nationalities to work its mines. Company officials contended that various ethnic groups, who could not speak each other’s language, would be less likely to organize into unions.

To live in what many saw as an inhospitable environment and do routinely dangerous work, laborers came from Croatia, Bosnia, Austria, Slovenia, Italy, Greece, Finland, England, Scotland, Ireland, Spain, France, China, Mexico, Germany, Russia, Korea and Japan. Eventually others came from Turkey, Armenia, Israel and Syria. Diversity became the hallmark of coal towns, surrounded by buttes and arid canyons. The draw was work.

In spite of all that Union Pacific did to prevent it, the company could not keep its coal miners from organizing. In 1907, the miners went on strike. This time, they achieved their objectives. The United Mine Workers admitted Japanese miners into the union, the industrial mines in Sweetwater County unionized, and the labor union won the strike.

During World War I, mines in the Rock Springs area sold as much coal as they could produce. Falling demand at the end of the war, however, dealt a blow to the coal industry.

Mineral riches

Eventually, and fortunately for the local economy, other minerals would be developed that would surpass even coal in their importance to Sweetwater County.

Sweetwater County is rich in natural gas. Hiawatha, Powder Rim, Granger, Table Rock and Wamsutter all have significant pockets of natural gas and some oil. But it’s natural gas that makes the region a world-class reserve of fossil fuels.

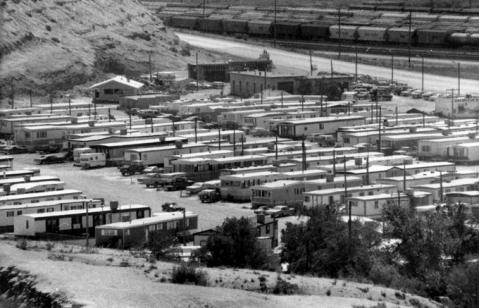

During the Great Depression, the natural gas industry grew. Only after World War II, however, did the gas reserves became significant. The war brought prosperity to the coal industry, but after the war, when the U.P. switched from coal-powered to diesel-powered engines, the coal mines shut down. Some people predicted Rock Springs would become a ghost town.

Instead, in the 1950s, growing production of the mineral trona west of Green River invigorated the local economy. At about the same time, uranium was found in the northeast corner of the county. These developments aided an economy weakened by the drop in coal production.

In the late 1930s, Mountain Fuel Supply Company, now Questar, had discovered mineral trona while searching for natural gas. The world’s largest deposits of trona, a natural sodium carbonate that is refined into soda ash for use in making glass, fertilizer and many other products, were found west of Green River. In 1948, the Food Machinery Corporation opened trona mines near the Mountain Fuel discovery. Currently, five facilities in Sweetwater County produce 90 percent of the soda ash in the United States.

More recently, the expansion of natural gas fields in places like Wamsutter helped increase economic growth in the county.

By 1991, thanks to all its minerals, Sweetwater County had the second highest assessed valuation of any of Wyoming’s 23 counties, standing at $773 million. Coal was valued, for tax purposes, at more than $190 million; natural gas, more than $185 million; trona, more than $179 million and oil, more than $177 million.

According to the 2005 Wyoming Department of Revenue annual report, state revenues from taxes on Sweetwater County property and minerals make the county one of the top three revenue producers in Wyoming—behind only coal-rich Campbell County and natural-gas-rich Sublette County. As such, Sweetwater plays a huge role in funding the state’s programs and operations.

Sweetwater County owes its wealth to extraction. That is, according to one homespun definition, taking something out of the ground that wasn’t grown. What the residents of Sweetwater County take from the ground continues to generate the county’s wealth, continuing an ancient pattern.

The Indians who first lived here took cherts from the ground that others valued. They traded their beautiful, tool-making stones—often banded agates or moss agates—to neighbors for other items equally prized.

Now, trona and natural gas are extracted from the ground and their various uses provide more economic value. The future lies in managing all these resources so that the wealth this land produces will help ensure the survival of future generations. Or as one old miner said, “Never sell cheap what you dig from the dirt.” The rocks beneath the surface, like the cliffs along the Green River that Moran painted so well, have value.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Bromely Isaac, The Chinese Massacre at Rock Springs Wyoming Territory, September 2, 1885. Boston: Franklin Press, Rand, Avery & Co., 1886. Accessed Nov. 7, 2012 at http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/4579566?n=1&s=4&printThumbnails=no.

- Bryant, Edwin, What I Saw in California; Being the Journal of a Tour by the Emigrant Route and South Pass of the Rocky Mountains, Across the Continent of North America, the Great Basin, and Through California, In the Years 1846, 1947. Minneapolis: Ross and Hainer, 1967 reprint.

- Jackson, Donald, and Mary Lee Spence, eds. The Expeditions of John Charles Fremont, Volume 1, Travel from 1838 to 1844. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970.

- Morgan, Dale. Overland in 1846: Diaries and Letter of the California-Oregon Trail. Georgetown, California: The Talisman Press, 1963.

- McDermott, John Francis, ed. An Artist on the Overland Trail - 1849 Diary and Sketching [of] James F. Wilkins. Huntington Library: San Marino, California, 1968.

- Nunis, Doyce B., ed. The Bidwell-Bartleson Party: 1841 California Emigrant Adventure: The Documents and Memoirs of the Overland Pioneers. Santa Cruz, California: Tanager Press, 1991.

- Palmer, Joel. Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains to the Mouth of the Columbia River; Made During the Years 1845 and 1846. Cincinnati: J. A. and U. P. James, publisher, 1847.

- Shutterly, Lewis. The Diary of Lewis Shutterly. Saratoga, Wyoming: Saratoga Historical and Cultural Association, 1981.

- Webber, Bert, ed. The Oregon and Overland Trail Diary of Mary Louisa Black in 1865. Medford, Ore.: Pacific Northwest Books Company, 1989.

State of Wyoming

- State of Wyoming Department of Revenue Annual Reports http://revenue.state.wy.us/PortalVBVS/uploads/DOR%20Annual%20Report%202011.pdf

U.S. Government Documents

- United States Department of Census. Seventh Census of the United States, 1850. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1852.

- ----------. Ninth Census of the United States, 1870. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1872.

- ----------. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1883.

- ----------. Eleventh Census of the United States, 1890. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1892.

- ----------. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1901.

- ----------. Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1913.

- ----------. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1922.

- ----------. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1931.

- ----------. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1942.

- ----------. Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1952.

- ----------. Eighteenth Census of the United States, 1960. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1952.

- United States Census 2010, accessed Nov. 8, 2012 at http://2010.census.gov/2010census/data/

Secondary Sources

- Cullen, Thomas P. Rock Springs: Growing Up in a Coal Town 1915-1938, Green River: Sweetwater County Museum Foundation, 2005.

- Del Bene, Terry, Ruth Lauritzen, Cyndi McCullers. Images of America: Green River. Chicago: Arcadia Press 2007.

- Frison, George C. Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains, second edition. New York: Academic Press, 1991.

- Gardner, A. Dudley and Verla R. Flores. Forgotten Frontier: A History of Wyoming Coal Mining. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1989.

- Gardner, A. Dudley and Val Brinkerhoff. Historical Images of Sweetwater County. Virginia Beach, Virginia: Donning Company Publishers, 1993.

- Harrell, Lynn L. and Scott T. McKern. Maxon Ranch: Archaic and Late Prehistoric Habitation in Southwest Wyoming. Rock Springs, Wyoming: Archaeological Services of Western Wyoming College, 1986.

- Harrell, Lynn L., Ted Hoeffer III, and Scott T. McKern. “Archaic Pit Houses in the Wyoming Basin,” in Changing Perspectives of the Archaic on the Northwestern Plains and Rocky Mountains, eds. Mary L. Larson and Julie E. Francis. Vermillion: University of South Dakota Press, 1997, 335-367.

- Johnson Clay and Byron Loosle, Prehistoric Uinta Mountain Occupations. Vernal, Utah: Ashley National Forest Heritage Report, 2-02, 2002.

- Isham, Dell. Rock Springs Massacre 1885. Lincoln City, Ore.: Quality Printing Service, 1985.

- Klein, Maury, Union Pacific, Birth of a Railroad 1862-1893. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Company, 1987.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978.

- McCullers, Cyndi. Images of America: Sweetwater County. Chicago: Arcadia Press 2009.

- Mclean, Karen Spence and Marjane Telck. Images of America: Coal Camps of Sweetwater County (Chicago: Arcadia Press 2012).

- Metcalf, Michael D. “Contributions to the Prehistoric Chronology of the Wyoming Basin,” in Perspectives on Archaeological Resources Management in the Great Plains (Omaha, Nebraska: I&O Publishing, 1987), 233-261.

- Proulx, Annie. Red Desert: History of a Place (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008).

- Rhode, Robert. Booms and Busts on Bitter Creek. Boulder, Colorado: Pruett Press, 1987.

- Tanner, Russel and Margie Fletcher Shanks. Images of America: Rock Springs. Chicago: Arcadia Press 2008.

- Wilson, Arlen Ray. "The Rock Springs, Wyoming, Chinese Massacre, 1885." Master's thesis, University of Wyoming, 1967.

Illustrations

- The photo of the Boar’s Tusk is by Erin McKinney of the Wyoming State Library, from the library’s Wyoming Places website. Used with thanks.

- The image of Thomas Moran’s “Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, 1881,” is from the National Gallery of Art, via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

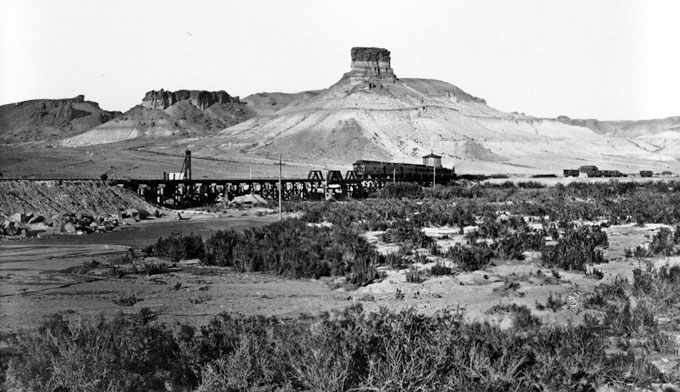

- The 1869 photo of Castle Rock and the U.P. Railroad bridge is by the pioneer photographer William Henry Jackson, from the U.S. Geological Survey photo library. Used with thanks.

- The pictures of the Sweetwater County Courthouse and the Routh Trailer Court are from the collections of the Sweetwater County Historical Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The picture of U.P. Coal mines numbers 7 and 9 is from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Boar’s Tusk is by Erin McKinney of the Wyoming State Library, from the library’s Wyoming Places website. Used with thanks.