- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Diamond Hoax: a Bonanza That Never Was

The Diamond Hoax: a Bonanza That Never Was

“One of the most barefaced, reckless, courageous, bold, ingenious, pre-meditated, carefully planned, deliberate, time-serving, colossal frauds ever known in the history of man.”

- Charles Dexter Cleveland

It began late in 1870 with two weather-beaten prospectors, cousins, originally from Kentucky, named Philip Arnold and John Slack. They appeared at the San Francisco office of George D. Roberts, a financier and businessman who, some said, was a man willing to move swiftly—perhaps too swiftly—when opportunities arose. They were carrying a leather bag containing something valuable, they said, which they’d been unable to deposit at the Bank of California due to the late hour. They wanted to find a safe place for it.

At first reluctant to talk, they finally revealed the bag’s contents to Roberts—rough diamonds, a lot of them, all from a fabulous gem field somewhere in the West’s vastness. They refused to discuss the location. Roberts agreed to absolute secrecy, a promise he immediately broke, telling two other men about the gems: William C. Ralston, founder of the Bank of California, and Asbury Harpending, an adventurer and one-time would-be Confederate swashbuckler.

The backers

Ralston, one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in California, had made his fortune investing in the silver bonanza that was Nevada’s Comstock Lode among other things. During the Civil War, Harpending traveled secretly to Richmond, Va., where he and several accomplices obtained a letter of marque—a piracy license—from Confederate President Jefferson Davis to outfit a San Francisco schooner named the J.M. Chapman as a privateer, sailing to capture gold on the high seas to support the Confederacy.

The scheme was thwarted by Union officers and the San Francisco Police; Harpending found himself arrested, convicted of treason, and sentenced to 10 years at the military prison on Alcatraz. Within a few months, President Lincoln granted amnesty to all political prisoners who would agree to take and keep the oath of allegiance. Harpending complied and was released in 1864. He’d been engaged since then in a variety of grandiose ventures—some successful, some not—in real estate, railroads and mining.

By 1870, both Ralston and Harpending were promoting a new project called the Mountains of Silver in New Mexico; Harpending at that time was in England seeking overseas investors. The two men were as enthralled as Roberts by the gem field story, and Harpending told a friend in London that he must “hurry home, as ‘they had got something that would astonish the world.’” And hurry he did, arriving back in San Francisco in May 1871.

Arnold and Slack had kept busy in the meantime. On a later visit to Roberts, they told him they’d returned to the diamond field and recovered 60 pounds of diamonds and rubies worth over half a million dollars. His enthusiasm mounting, Roberts drew two more prominent mining entrepreneurs into the mix: Gen. George S. Dodge, a former Union Army officer and William Lent who, like Ralston, had been a prominent investor in the Comstock Lode.

“Finding” the gems

Still keeping the diamond field’s location a strict secret, in return for an investment/partial buyout of $50,000 in cash, Arnold and Slack agreed to return there and bring back even more stones, which they claimed would be worth millions. The San Francisco investors agreed.

The pair left San Francisco, headed not for any spectacular frontier field of gemstones, but for London. There, under assumed names, they purchased about $20,000 worth of rough, uncut diamonds and rubies from a London gem merchant. With these they returned to San Francisco and presented the stones, thousands of them, them to Roberts, Ralston, Harpending, Dodge and Lent as their latest haul from their remote gemstone field. Spread out on a sheet on Harpending’s billiard table, as he would later write, the stones “seemed like a dazzling, many-colored cataract of light.”

|

And well they might, for they were real. In fact, all the stones Arnold and Slack produced were genuine, if very low-grade. As a bookkeeper for a San Francisco drill manufacturer that used diamond-tipped bits, Arnold had shown great interest in the industrial-grade diamonds used and almost certainly helped himself to cast-offs. It was these he and Slack showed Roberts during their first visits to his office, mixed with rubies, garnets and sapphires likely purchased from Indians in Arizona; the rest were bought in England.

Tiffany’s appraisal

It was decided that 10 percent of this batch of stones would be taken to New York for examination and appraisal by Charles Lewis Tiffany of Tiffany & Co., the iconic jewelry store still in business in Manhattan. Among others present at the appraisal were Maj. Gen. George McClellan of Civil War fame and a one-time presidential candidate, Congressman Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune and several high-profile bankers. Tiffany pronounced the gems genuine, setting their value at about $150,000, which, by his call, made the latest stones delivered to the partners worth $1.5 million.

Back in San Francisco, the investors formed the San Francisco and New York Mining and Commercial Company. To promote the sale of shares of stock in their venture, they displayed trays of the gems in jeweler William Willis’s window.

Jumping off from Rawlins

Though by now completely dazzled, the investors set a final condition. Arnold and Slack had yet to reveal the diamond field’s location, and they not only wanted the pair to guide an inspection team to the site, they wanted an independent expert of their choice, a much-respected mining engineer named Henry Janin, to go along. The Kentuckians agreed, with one condition: the party would be blindfolded along the final leg of the journey.

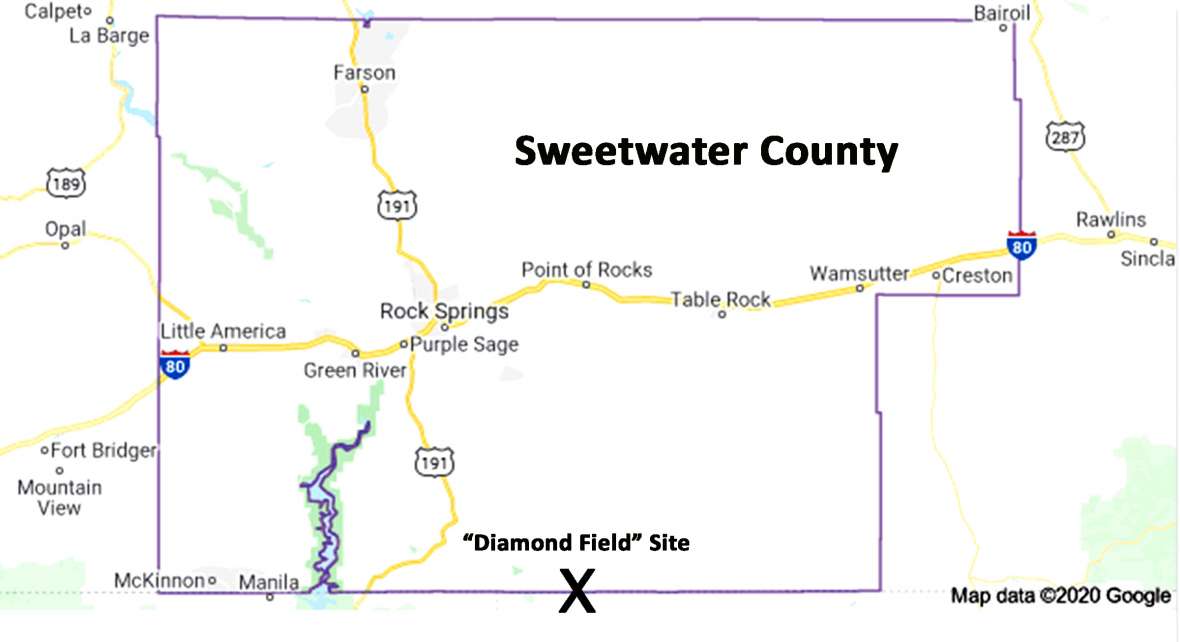

In June of 1872, the inspection party—Arnold, Slack, Janin, Dodge, Harpending and an English friend of Harpending’s named Alfred Rubery—traveled by train to Rawlins (sometimes identified in older accounts as “Rawlings” or “Rawlings Springs”), in south-central Wyoming Territory. From there they continued on horseback.

For four days, Arnold and Slack led the group along a confusing, circuitous route through long stretches of rough country. The two often appeared to be (or pretended to be) lost and had to climb heights along the route to get their bearings. On June 4, they arrived at the spot, a broad mesa dominated by a cone-shaped mountain to the south.

Within only a few minutes, “Rubery gave a yell. He held up something glittering in his hand. It was a diamond, fast enough. Any fool could see that much. Then we began to have all kinds of luck,” Janin recalled later. “For more than an hour diamonds were being found in profusion, together with occasional rubies, emeralds and sapphires ...”

A “wildly enthusiastic” Janin reported the gem field to be absolutely genuine and the news swept the nation and beyond. Even the London banking firm of Rothschild, which had financed the British government’s purchase of the Suez Canal from Egypt for £4 million, expressed interest.

When he wasn’t picking up gemstones, Janin busied himself staking out three thousand acres of land at the site. His investors-paid fee was $2,500, but he’d also been offered a thousand shares of company stock at $10 per share. Upon his return to New York he sold his shares for $40 apiece—a $30,000 profit.

Escape—and exposure

Around this point, the Kentuckians Arnold and Slack cashed out. Slack’s take from the investors totaled $100,000; Arnold’s, $550,000 minus expenses. Together they’d bilked their backers of $650,000—well over $13 million in 2020 currency. Slack promptly dropped out of sight and Arnold returned to Elizabethtown, Ky. with his family.

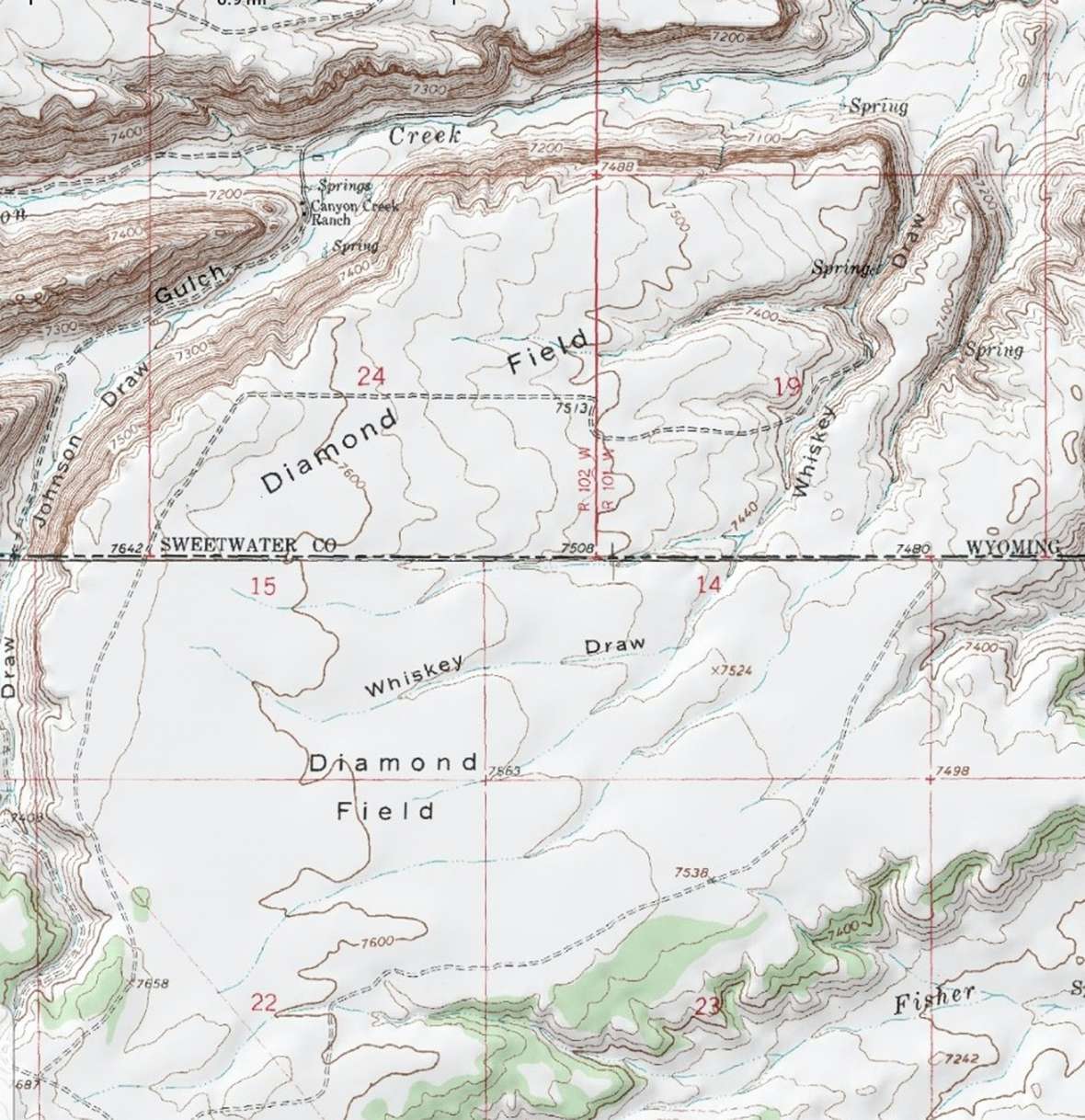

The entire affair was arguably the biggest swindle in the history of the frontier West. Arnold and Slack had “salted” the mesa, which straddles the Wyoming-Colorado border about 44 miles south of Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory, with low-grade diamonds and other gemstones. To this day, the mesa is officially marked on U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps as “Diamond Field.”

Coincidence and first-rate detective work collapsed the hoax. Clarence King, a Yale-educated geologist, was at the time leading the final stages of a U.S. government survey of the mineral, agricultural and other resources of 80,000 square miles of ground along the 40th parallel of latitude. Their investigations followed a wide swath of land along the transcontinental railroad from the Rocky Mountains to the Sierra: King and his crews would already by this time have had a good sense of that part of the West. King’s was one of four surveys that by the end of the decade would be combined into the U.S. Geological Survey.

In October 1872, one of King’s men, geologist Samuel Emmons, encountered Janin aboard a train in California, where Janin showed him several of the diamonds found at the Arnold-Slack site. Suspicious, Emmons reported the contact to King who, equally suspicious, tracked down Janin in San Francisco and interviewed him. Both Emmons and King knew that rubies and sapphires are seldom found exactly where diamonds are.

As previously noted, Janin had been blindfolded during the horseback trip from Rawlins. King’s questions were astute, however, and he made some excellent deductions about the “diamond field’s” location.

In October 1872, King organized a party and traveled to Fort Bridger, WyomingTerritory, where his surveying team had boarded a number of mules. In bitter cold, they set out east and in about a week, reached the Wyoming-Colorado border south of Rock Springs, from which they observed a cone-shaped mountain and the mesa much like those Janin had described. The mountain, 3.5 miles south of the state line, is now aptly named Diamond Peak.

Near the mountain, King’s party began a search and found a sign claiming water rights in the area signed by Henry Janin, confirming that they’d found the Arnold-Slack Site.

“A short time later ... they began to find several gems,” historian Sharon Hall recounts. “Curiously, they didn’t find many diamonds but by the next morning they had found amethysts, spinels and garnets. King then found a diamond perched precariously on a slender rock—how in the world could the stone remained perched for hundreds of years?

“Upon further observation King and his group discovered that every anthill on the ridge had a series of tiny holes, perhaps eight inches deep and made with a stick or some other instrument. At the bottom of each was a precious gem, obviously fraudulently ‘salted’ there by whoever dug the holes. The bankers, financiers, mining engineers and even renowned jeweler Charles Tiffany had all been duped!” Hall concludes.

Once the hoax imploded, it became clear that a shame-faced Charles Tiffany didn’t know much about uncut stones. Janin too was hoodwinked, though that didn’t stop him from making a tidy profit from his stock sale.

Arnold and Slack were both indicted in California for fraud, but never brought to trial. Arnold was sued by investors in the “diamond field” and settled out of court. Eventually he became a banker in Elizabethtown, and was shot in 1878 by a business rival. While recovering from the gunshot wound, he contracted pneumonia and died six months later. Slack reportedly died in New Mexico in 1896.

In 1879, Clarence King was appointed the first director of the United States Geological Survey. In 1881, he was permitted to name his own successor: John Wesley Powell, explorer of the Green and Colorado Rivers and the Grand Canyon and one of the great thinkers about the American West.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Harpending, Asbury. The Great Diamond Hoax and Other Stirring Incidents in the Life of Asbury Harpending. San Francisco: The James A. Barry Company, 1913.

Secondary Sources

- Boessenenecker, John. Badge and Buckshot: Lawlessness in Old California. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.

- Elliott, Ron. American El Dorado: The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872. Sikeston, Mo.: Acclaim Press, 2013.

- Hall, Sharon. “Far-Out Friday: The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872.” Digging History, Jan. 3. 2014, accessed March 5, 2020 at https://digging-history.com/2014/01/03/far-out-friday-the-great-diamond-hoax-of-1872/.

- Moore, James Gregory. King of the 40th Parallel: Discovery in the American West. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford General Books, 2006.

- Wilson, Robert. The Explorer King: Adventure, Science, and the Great Diamond Hoax - Clarence King in the Old West. Berkeley, Calif.: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2006.

- _____________. “The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872." Smithsonian Magazine, June 2004, accessed March 5, 2020 at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-diamond-hoax-of-1872-2630188/.

- Winchester, Simon. The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics, and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible. New York: Harper/Harper Collins, 2013.

- Woodard, Bruce Albert. Diamonds in the Salt. Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Press, 1967.

Illustrations

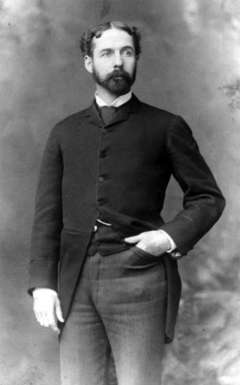

- The photo of Philip Arnold is from alchetron.com. Used with thanks.

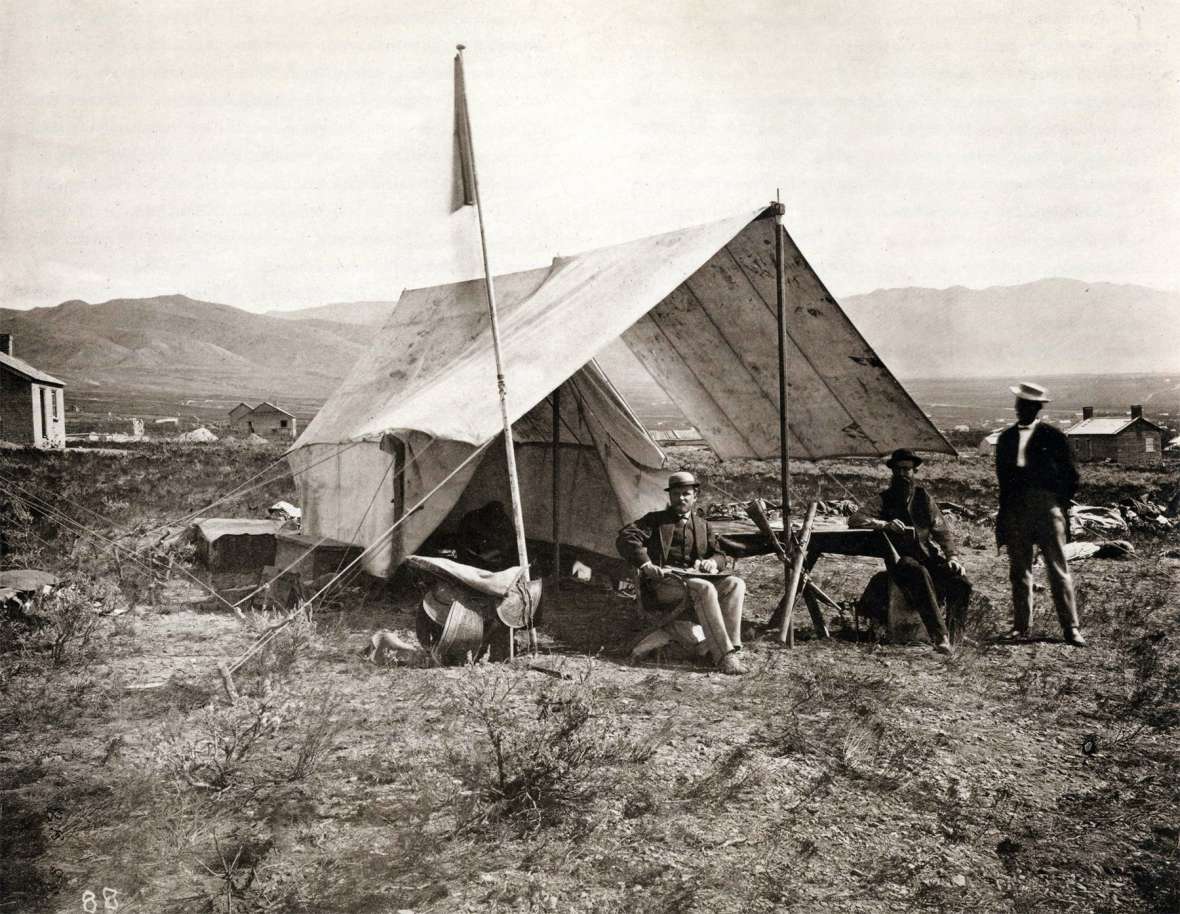

- The photos of William Ralston, Charles Tiffany, Samuel Emmons and the Timothy O’Sullivan photo of Clarence King in camp at Salt Lake City, 1868, are from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photos of Asbury Harpending and Alfred Rubery are from Harpending’s autobiography, The Great Diamond Hoax, first published in 1913.

- The locator map is by the author, used with permission and thanks. The contour map is a detail from two US Geological Survey 7.5-minute quadrangle maps: the Scrivener Butte quadrangle in Wyoming and the Sparks quadrangle in Colorado. Special thanks to the author for assembling the image and the staff at the Natrona County library for locating the quads.