- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Lynching of Joe Martin

The Lynching of Joe Martin

Editior's note: Research assistance by Clint Black contributed to this article.

Monday, Aug. 29, 1904, started out as a normal, warm, sunny Laramie day. The semi-weekly Laramie Boomerang devoted its front page to a problem with state fishing laws and its back page to a prizefight in San Francisco.

By the end of the day the community would be the scene of an act of racial hatred. An African-American man, Joe Martin, was forcibly taken from the county jail and lynched just across the street, at the corner of Sixth Street and Grand Avenue.

So-called vigilante justice in Wyoming, best exemplified by the invasion of Johnson County in 1892, was tapering off by 1904. The big cattlemen’s hired killer, Tom Horn, was convicted and legally hanged in Cheyenne in 1903. Murders of sheepmen continued a while longer in the Bighorn Basin, however, ending with the successful prosecution of the perpetrators of the Spring Creek Raid in 1909.

Those were all murders of White men. Martin’s death, by contrast marks the beginnings of an intense decade and a half of Wyoming lynchings of Black men. By the 1910s, according to scholar Todd Guenther, Wyoming was lynching Black men at a rate 30 times as great as was occurring at the same time in the deep South. Guenther concluded these were crimes meant not just to punish individuals, but to terrorize a population.

New arrivals in town

A major figure in the Martin drama was Della Krause, a 22 year-old Chillicothe, Mo., native who arrived in the area as early as July when she was reported in the Laramie Republican newspaper as visiting Centennial with 38 year-old William Benton. By late August she was working in the courthouse kitchen, helping to prepare meals for prisoners in the county jail. She was sometimes referred to as a guest of Mrs. Alfred Cook, the sheriff’s wife.

Not much is known about Joe Martin. Some reports indicate he arrived in Laramie from Ogden, Utah, possibly early in 1904. Other reports stated that he had been in the Wyoming State Penitentiary serving a three-year sentence for a “heinous crime.” He worked as a janitor at a local saloon.

Thirty-five year-old Martin was arrested in Laramie on three occasions. In February, Martin was fined five dollars and sentenced to jail time for threatening a cook at the Chrissman Hotel. In March, he was arrested for threatening a man with a knife. Those charges were dropped.

Then in April, Martin was arrested and sentenced to six months in the county jail and fined $50 for sending an obscene letter to Maud Cummings who was working at the Kuster Hotel. Justice of the Peace M. N. Grant stated that he wished the law allowed for a stiffer sentence. During his incarceration, Martin was granted “trusty” status by Sheriff Cook.

The Weekly Boomerang concluded its report on the sentencing, “The Negro has a bald head and slouches as he walks but prides himself upon the nickname of the ‘Kansas City Dude.’"

Attack on jailhouse worker

On Aug. 29, “trusty” Martin was out of his cell performing work around the courthouse, and about 1:30 p.m. he went to the basement kitchen where Krause was assisting Mrs. Alfred Cook in the preparation of meals for the seven prisoners. Details of exactly what happened next are not clear, but the newspaper coverage made it appear that Martin made suggestive comments to Miss Krause. As there was no trial, the true facts of the case will never be known.

When he was rebuffed, Martin reportedly seized a razor and attacked Krause. Before he could be subdued by Mrs. Cook and her son Alden, he managed to slash Krause four times on the neck, right cheek, nose and near her left eye. Reports at the time said she would be “disfigured for life.”

In an article that day titled “Negro Fiend,” the Cheyenne-based Wyoming Tribune reported Sheriff Cook intervened and “beat the Negro nearly to death and threw him into a cell.” Later, jailor A.J. Jones realized that Martin’s condition was such that Dr. S.B. Miller was called to attend to his injuries.

Anger swells among townsfolk

Word of the attack on Della Krause circulated around town later that day.

The Laramie Republican reported that angry mutterings and some open threats of summary vengeance were heard. After the stores closed, a considerable crowd of men gathered downtown at the corner of Second and Thornburgh St. (now Ivinson Ave.) with “one subject of conversation and their eyes to the east” (toward the courthouse). Policemen came to the scene but did not intervene as the crowd eventually surged up the street.

Assault on the courthouse

By 8 p.m., between 200 and 300 men reached the courthouse. Immediately the leaders of the mob entered the building. At this point, reporting on the events becomes confused. Most papers wrote that the men, who were not masked, demanded Sheriff Cook turn over the keys to the jail. When he refused, not-so-subtle threats of violence persuaded him to do so.

Yet the papers also reported that the men battered down the cell doors with sledges and axes. This commotion was apparently loud enough to cause a much larger crowd, variously reported to be between 1,000 and 2,000 residents, to assemble on the courthouse grounds to see what was going on. Laramie’s population at the time was just over 8,000, and women and children were reported in the crowd.

In any case, the leaders of the mob were able to enter Martin’s cell, direct Dr. Miller and jailor Jones to face the wall and drag Martin toward the exit. In the struggle, Martin apparently injured as many as six of the men either with a knife he grabbed from the kitchen or with part of the cell bed that was broken in the struggle.

Other reports said that Martin used the knife to attempt suicide by slashing his own throat.

The lynching

Once outside the courthouse, several men put a rope around his neck and dragged Martin toward the intersection of Sixth Street and Grand Avenue. During the short journey, excitement built in the crowd, and men fired multiple shots into the air until the leaders demanded they stop.

In their recap of events titled “Poor Shots,” the Laramie Boomerang the next day described the action as a “lynching bee” and that “Matin [sic] The Degenerate” was taken to the southwest corner of the intersection. A man shinnied up the streetlight pole and flung the rope around the crossbar. Several men then hoisted Martin off the ground. The Laramie Republican reported, “A hundred willing hands seized the noose and began to draw the Negro upward.” The rope slipped and Martin was again hoisted up.

Someone in the crowd, fearing apparently that Martin was not dying fast enough, shot him at least once with what the coroner later said was a .32 caliber weapon. That did not end the struggle, and Martin slowly strangled to death.

As the crowd silently moved away, acting coroner M.N. Grant who was at the scene ordered the body cut down, and Sheriff Cook took possession. It was soon reported in the Cheyenne Wyoming Tribune newspaper that William Frazee, state senator and homeowner across the street from the lynching scene, and Nellis Corthell, county commissioner and principal owner of the Laramie Boomerang, made lists of names of the participants.

The aftermath

Neither the Laramie Boomerang nor the Laramie Republican editorialized on the actions of the lynch mob. But the Boomerang did blame the whole affair on the “trusty” system. Had Martin not been allowed to work outside of his cell, they argued, he would not have been able to attack Krause. The general tenor of both papers’ coverage was that Martin got what he deserved.

In contrast, both the Rawlins Republican and the Cheyenne Leader newspapers condemned the event. The Rawlins paper called it “a blot on the fair name of the state.”

Although the reporter for the Cheyenne Leader used inflammatory language about the lynching, the editor wrote strong words: “All good citizens of Wyoming must regret the deplorable event which took place in Laramie last evening. The provocation for the lynching of the Negro Martin was certainly great, but it would have been better for the fair name of Laramie and the State of Wyoming had the people of the Gem City, in their anger, remembered that two wrongs do not make a right.”

Not much more was written about the lynching until District Judge Charles Carpenter returned to Laramie from Casper where he had been presiding over several cases. On Sept. 20th he convened a grand jury to examine three incidents, a shooting in northern Albany County, a case of selling liquor on Sunday and the Martin lynching.

The grand jury

The men called to be jurors were George Campbell, Elmer Lovejoy, George Chapman, Leander Keyes, Martin Beck, F. P. Mason, A. Johnson, William Isberg, Frank J. Terry, Frank Vorpahl, C. P. Lund and Peter Cunningham. Campbell was selected foreman.

Judge Carpenter then gave his charge to the jury. After discussing the other two incidents, he addressed the lynching. Characterizing the act as an “outrage upon moral law and upon this community and state,” he told the jurors that only the courts were authorized to deal with Martin no matter the nature of his offense. Carpenter then noted that any men, women and children who witnessed the lynching should come forward to offer evidence.

Carpenter concluded with this statement: “Every man who participated in this lynching and murder, by actual participation or who aided, abetted and counselled the same is guilty of the highest crime known to the law.” He then tasked the grand jurors to carry out their sworn duty “faithfully and fearlessly.”

The jury was conducted by County Attorney Thomas H. Gibson. Immediately several witnesses were called to testify. Among those were three with first-hand knowledge of the lynching: Judge M.N. Grant, Sheriff Alfred Cook and William Frazee. Strangely, Nellis Corthell was not called despite indications in the Cheyenne newspaper that he had a list of the perpetrators.

Grand jury deliberations were done in secret. None of the members leaked information about how they proceeded. In the end, however, the jury indicted no one for the lynching of Joe Martin despite multiple eyewitnesses and clear violations of the law. They did, however, indict druggist Thomas Eggleston in an unrelated case, for selling three glasses of wine at his store at 40 cents each to friends on a Sunday. He was charged and arrested for violating Sunday closing laws.

Moving on

The Laramie lynching made national news. Some papers added lurid, untrue details. For example, one paper said Martin gouged out Krause’s eye. The notoriety was short-lived. Della Krause married Alden Gray, the adopted son of Sheriff Alfred Cook, in 1908 and they later moved to Los Angeles. The sheriff did not run for reelection and later worked as a butcher and manager of a secondhand store.

William Frazee ran his clothing store for several years before moving to Salt Lake. Nellis Corthell continued his law practice and political career. Judge Charles Carpenter served on the bench until 1912 when he died of kidney disease. Thomas Gibson, the county attorney, continued in the practice of law and lost a bid to be elected to the Wyoming Supreme Court.

Joe Martin is buried in potter’s field in Greenhill Cemetery. His grave is within sight of Judge Carpenter’s.

Editor’s note: Special thanks to the author and to the Albany County Historical Society, where an earlier version of this article first appeared.

Resources

Primary sources

- Cheyenne Daily Leader. Aug. 30, 1904, p. 1, col. 3; Aug. 30, 1904, p. 4, col. 1; Sept. 14, 1904, p. 7, col. 3.

- Laramie Boomerang. March 5, 1904, p. 4, col. 2; April 2, 1904, p. 1, col. 2; April 3, 1904, p. 1, col. 6; April 4, 1904, p. 1, col. 2; Sept. 14, 1904, p. 2, col. 2; Sept. 20, 1904, p. 1, col. 1-3; Sept. 21, 1904, p. 1, col. 4; Sept. 23, 1904, p. 1, col. 3-5; July 18, 1908, p. 1, col. 3.

- Laramie Republican. Feb. 4, 1904, p. 1, col. 4; May 16, 1904, p. 2, col. 3

- Rawlins Republican. Aug. 31, 1904, p. 1, col. 1.

- Wyoming Tribune. Feb. 5, 1904, p. 3, col. 3; March 8, 1904. p. 2, col. 4; Aug. 29, 1904, p. 5, col. 3; Aug. 30, 1904, p. 5, col. 1-2; Sept. 12, 1904. p.5, col. 3.

Secondary sources

- Guenther, Todd. “The List of Good Negroes: African American Lynchings in the Equality State.” Annals of Wyoming 81, No. 2 (Spring 2009): 2-33.

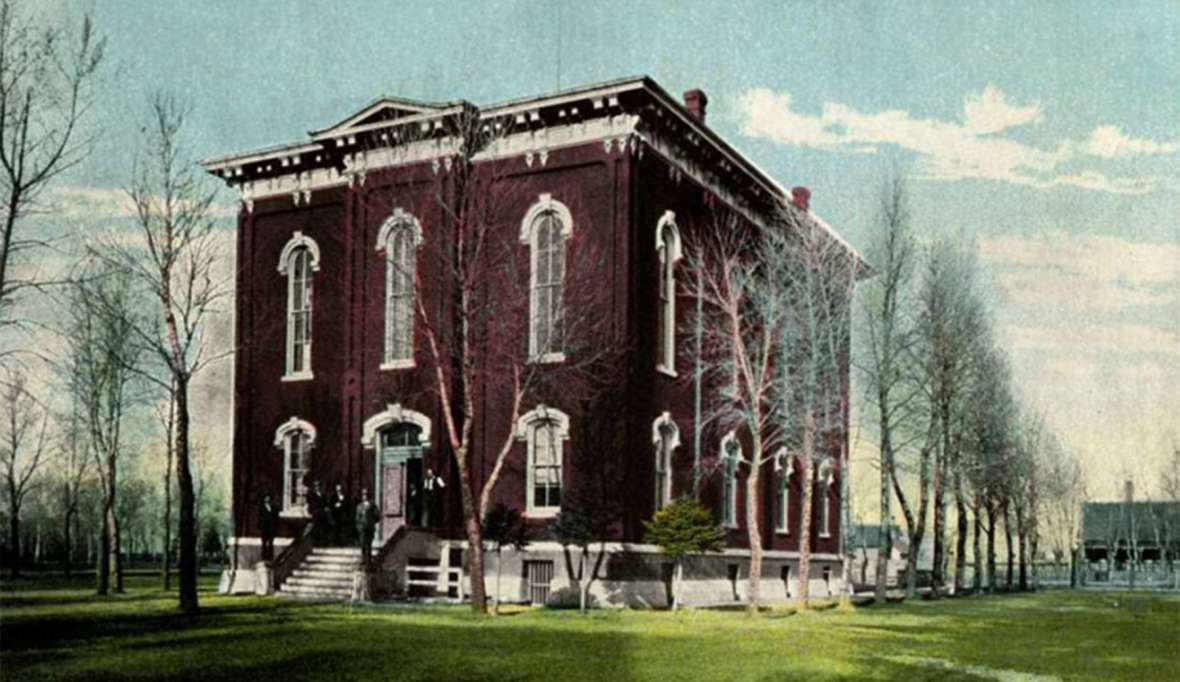

Illustrations

- Both photos are from the author’s collections, the photo of the courthouse from the Laramie Plains Museum and the photo of the Albany County Bar Association originally from the Albany County Clerk of District Court. Used with permission and thanks.