- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Frontier Index: “Press On Wheels” In a Part...

The Frontier Index: “Press on Wheels” in a Partisan Time

When the Union Pacific railroad tracks reached Cheyenne in the fall of 1867, three little newspapers had already appeared on the streets of what soon would become Wyoming Territory’s capital.

But the Frontier Index, which began publication in Wyoming a few months later, has attracted the most attention from newspaper historians during the past 150 years. The Index came to be called the “Press on Wheels” as it was published in five or perhaps six end-of-tracks towns that sprang up in southern Wyoming (then Dakota Territory) as the railroad’s graders and track-layers moved across the coal-rich southern part of the future state in 1867-68.

Press equipment for the Index was hauled by ox wagons ahead of the tracks from Kearney, Nebraska Territory, to North Platte, N.T., to Julesburg, Colorado Territory and then to Fort Sanders, just south of what soon became the town of Laramie. There, the Index was issued for the first time in Wyoming. Subsequently it was headquartered in Laramie, perhaps in Benton—east of present Rawlins near where the tracks crossed the North Platte River—Green River City, Bryan and southeast of present Evanston at Gilmer, which soon was renamed Bear River City at the request of the Index’s publisher.

The Index has also drawn attention because of the blatant anti-African American, anti-Native American and anti-Chinese attitudes displayed often in its pages by its owners and editors, two brothers from Virginia named Legh and Fred Freeman. The Freemans had served the rebel cause in the Civil War and, afterward, were dead set against giving the vote to African Americans. In essence they were white supremacists, still fighting. They hated Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, calling him “Useless Slaughter Grant—” an allusion to the hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers under his command who died in the war—and they hated his Republican allies’ Reconstruction program to extend civil rights to the formerly enslaved.

In those years the Republican Party was still the party of Lincoln. This was the party that had joined Abolitionism to the Union cause, had won the war and pushed through the revolutionary 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution—ending slavery, extending citizenship to former slaves and the vote to men of color. In coming decades the Republican party would abandon those priorities and transform into the party of business enterprise and corporate power.

The Freemans were Democrats, members of the party that traced its roots to Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. Its members saw themselves as the party of small farmers, small government and white men. Not until the 1930s did the party begin paying at least lip service to civil rights for black people. In the 1960s, when Democrats pushed through the Civil Rights Act, southern whites switched to the Republican Party.

During the Civil War, many Northern Democrats had little sympathy for the abolitionist cause and hoped for a peace settlement for the Confederacy. Angling for more unity in the North’s war effort, Lincoln, when he ran for president a second time in 1864, chose as his running mate Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee. When Lincoln was assassinated at war’s end, Johnson became president.

In the spring of 1868, the Republican-dominated Congress impeached but failed to convict Johnson, who had strong sympathies for the previously slaveholding class in the South and had turned out to be the most outspokenly racist president the nation has seen. That summer, the Republicans nominated Grant for president: the Index thus was published across the future Wyoming in an election year of deep divisions and partisanship.

The Index, perhaps out of old, anti-Union Army sentiments, also frequently criticized the U.S. Army units sent west to protect the railroad builders. The paper charged that Gen. John Gibbon, a veteran of Bull Run and Gettysburg, was misusing government funds for private gain at Fort Sanders.

Finally, the Index unintentionally achieved a sort of immortality when its support of a vigilante mob’s hanging of three robbers—“garroters,” they were called in the paper—led to a riot at Bear River City by liquored-up graders and outlaws who freed a fellow railroad grader from the newly-built jail and then burned the Index’s office and destroyed its presses.

This occurred Nov. 20, 1868. Grant had been elected president 17 days earlier. Though reports of whether anyone was killed during the riot are contradictory, Legh Freeman could very well have been a casualty if he had not been warned of the mob’s approach and escaped on horseback.

The Freemans

Frederick Kemper Freeman and Legh Richmond Freeman were born in Culpeper, Va. northeast of Charlottesville in 1841 and 1842, respectively, two of 12 children in the farming family of Arthur B. and Mary Freeman. They had slaveholders among their ancestors. One of the ancestors was an overseer for Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. An uncle on their mother’s side would become the first post-war native-son governor of Virginia from 1875-79.

Their father for a time was a railroad depot agent at Gordonsville, Va., which is most likely where Legh learned telegraphy. He served as a telegraph operator in the Confederate Army until he was captured in May 1864 in eastern Kentucky and held at a Union prison on Rock Island in the Mississippi River between Illinois and Iowa. Frederick served in the signal corps.

In October 1864, Legh took advantage of a call from President Lincoln for prisoners at Rock Island to swear allegiance to the North and be sent west to man forts and protect Oregon Trail travelers. Thus, on the day in April 1865 when the South surrendered at Appomattox, Legh the “galvanized Yankee” arrived at Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, and became a telegraph operator there.

The Kearny Herald had been founded in 1862 by Moses H. Sydenham, who sold it to Hiram Brundage, also a telegraph operator, and Seth P. Mobley, a cavalry soldier. (Brundage had previously published the first printed newspaper in what would become the state of Wyoming, the Daily Telegraph, while he was the telegraph operator at Fort Bridger in southwest Wyoming in 1863.)

Legh Freeman bought out and began publishing the Herald and, according to a 1979 biography of Legh, he interviewed Jim Bridger. Many years later, Sydenham recalled Legh Freeman as “a red-hot, unreconstructed ‘secessionist’ fresh from the southland.” But Legh soon developed a case of wanderlust, so he asked his brother Frederick in 1866 to come to Kearney and take over the newspaper.

During the next three months Legh traveled to California, Arizona, Nevada and Utah, often sending dispatches back to his brother for publication in their Index, sometimes under his nom de plume “Gen. Horatio Vattel, Lightning Scout of the Mountains.” During this time the brothers in their Index began frequently promoting the founding of a town named Freemansburg along the Colorado River in western Arizona, which never materialized. They predicted their town would become the capital of a new state of Aztec.

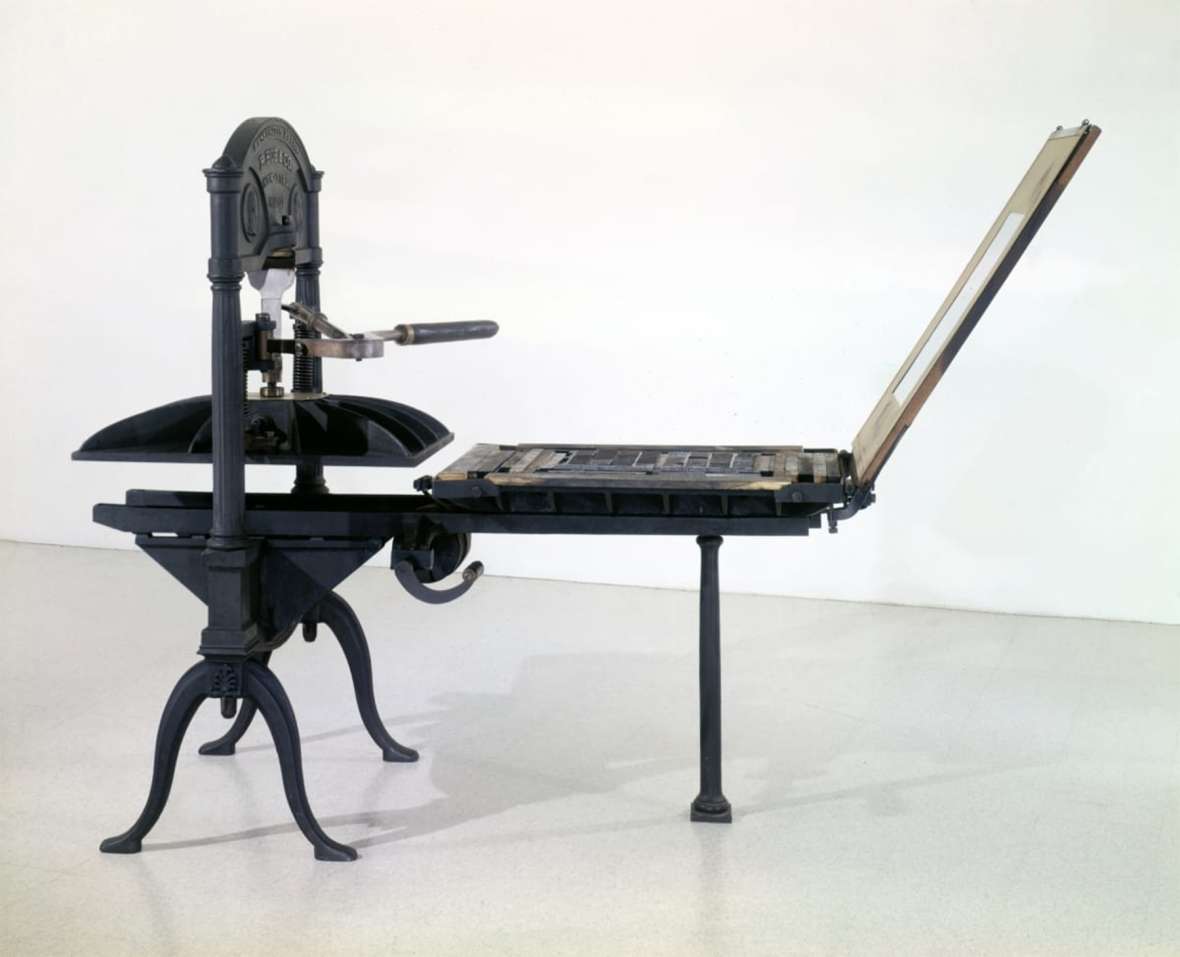

So Frederick edited and published their newspaper as it moved with the railroad builders. After moving to North Platte, N.T., the Freemans acquired a new Washington hand-press and the paper was renamed the Frontier Index.

Boosting towns and bashing tribes

Because the transcontinental railroad route dipped a short distance into Colorado Territory at Julesburg, Freeman published some issues of the Index there before moving the press ahead of the track layers to Cheyenne. Researchers have concluded that they did not publish any papers in Cheyenne; soon the brothers moved on across the Laramie Mountains to Fort Sanders ahead of the tracks. During this trip the wagon carrying their press and type cases capsized and ran over Fred in 20-degrees-below-zero weather. A wagon and personnel were sent from Fort Sanders to rescue him.

Many of the Indexes published in Wyoming can be searched and read at the Wyoming Newspaper Project’s web site. Many other issues have not survived. One hallmark of the existing issues of the four-page paper was its hyperbolic boosterism. Even before the tracks reached Laramie in May 1868, the Frontier Index was already proclaiming the Union Pacific would choose Laramie as its chief “half-way” city between Omaha and Utah, and that Cheyenne, often referred to derogatorily as “Shian,” and its newspapers would soon dry up and blow away.

The April 21st issue, for example, said that none of the railroad towns established through Nebraska and Wyoming “have one-hundredth part of the natural advantages that Laramie boasts of,” such as iron and copper ores, “coal cropping out from one end of the plains to the other,” gypsum, gold and silver, timber and “very attractive farming lands of which this whole valley is composed.”

Fred Freeman then exclaimed: “[T]ell us if we have not reached the real paradise of the western world. ... Laramie will prosper and become the pride of western people. ... The valley of the Nile offered not one half the flattering inducements to early settlement that we find here in this magnificent valley.” As late as September 1868, the Index was predicting that “Laramie will undoubtedly be the permanent capital of our new Territory.”

A week later, Freeman predicted that in six months “Shian will be composed of two saloons, two dance-houses—and another saloon.”

Another theme prominent in the Index’s pages was a hatred of Indians and, even more so, of the government’s “Commishers—” peace commissioners—including Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. The peace commission that spring negotiated a treaty at Fort Laramie between the plains tribes and the whites pouring into the West. “[H]ow kind it is in Sherman and the balance of the peace commissioners,” Legh Freeman noted sarcastically in the September 22 edition, “to give [the tribes] arms, ammunition and scalping knives to flay the frontier Democrats.”

On May 22nd, Freeman predicted that the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant to run for president on the Republican ticket would bury “the Republican party forever, and guarantees the victory of the Democratic or white man’s ticket.” At Green River City in August, the Index predicted that Grant’s Republican platform “will Africanise and Indianise our whole mountain region.”

In every issue the Index promoted the Democratic national ticket of Horatio Seymour for president and Francis Preston Blair for vice president.

An election year

In its June 9th issue, the Index described a visit to Laramie by railroad of eight carloads of New Yorkers and Chicagoans, including reporters from the leading newspapers. First they went on west to watch the track-laying and then returned to visit the gambling, dance and music halls of Laramie. “One Chicago gent remarked that our town was despretely [sic] wicked; we replied that the only difference between Laramie and eastern towns is that the people of Laramie are open and above board in all of their dissipations, while eastern people kept all of theirs behind the curtain,” Freeman wrote. (The June 30th issue reported a man found literally dead-drunk “in Askew’s tent. Death caused by excessive dissipation.”)

On June 16th the Index said Alexander Pyper of Salt Lake City was in Laramie preparing for 8,000 European emigrants on their way to join the Mormons in Utah. “They will start overland [by wagon train] from Laramie,” the report said.

On June 26th the Index discussed proceedings in Washington aimed at carving a new Territory of Wyoming out of southwestern Dakota Territory. Backers of Colorado statehood opposed the idea, the Index reported, because they wanted to have the population the railroad would bring included as part of Colorado. The Index also declared that when Wyoming Territory was created, “intelligent Western men should be appointed as territorial officers rather than “old, worn out Eastern politicians.” President Grant did not follow this advice.

On June 30th, the Index noted that its editor Fred K. Freeman had been appointed a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in New York City beginning July 4th. On July 3rd the Index said the 4th should be celebrated as the day on which the Convention meets “to frame a platform that will insure regenerated Independence of the white race.”

In the law enforcement report on July 7th the Index reported arrests for “females on the streets in male’s costume.”

Green River City

By Aug. 11, 1868, the Frontier Index had arrived by ox train at Green River City, Dakota Territory—the present Green River, Wyo. That issue includes a description of Legh Freeman’s previous railroad trip to the end of tracks at Benton. At Benton, the Index reported, Grant had given a campaign speech and afterward, “Buffalo Bill mounted a dry goods box at a street corner and returned thanks to the people for the splendid ovation (that was not) given.”

Also at Benton, Freeman met “a very prominent individual who thought a negro was as good as a white man, and a darned sight better than some white men.” Freeman replied that he thought “a ring tailed monkey was better than any white man who seeks to degrade anglo-saxons by comparison with any inferior race.”

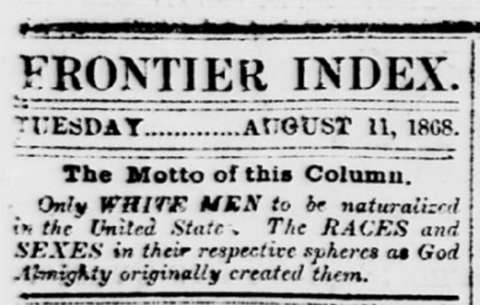

This and subsequent issues included “The Motto of this Column:” “Only WHITE MEN to be naturalized in the United States. The RACES and SEXES in their respective spheres as God Almighty intended them.”

As they moved to Green River the Freemans called their paper “the Star of Empire taking its way westward” and “the official organ of the Armies of Masonic Democracy.”

Legh told his readers that Gen. Grenville Dodge, the Union Pacific’s chief engineer; Jack Casement, boss of the UP construction; and Col. John Wanless, “the proprietor of the largest wholesale houses at Laramie City and Fort Sanders,” were in town “looking after the winter terminus interests. Wanless seized our hand with ‘Is this Leg[h]? ... I left your brother (Hon. Fred K. Freeman) in New York as high as a kite!’”

In a 1903 article reviewing Legh Freeman’s time as a newspaper publisher in Ogden, Utah in the mid-1870s, the Ogden Standard said Legh “was a strong anti-‘Mormon.’” But it certainly appears he held a different view in 1868, as shown in a long discourse in the Sept. 18, 1868, Frontier Index, after a reader asked him what he thought of the Mormons:

We favor [the Mormons] because they are white people who have improved a savage desert waste when they were isolated thousands of miles from the necessaries and comforts of life and because they are white we want to see their one hundred thousand people ... admitted to the rights of citizen-ship before the polygamy-practicing Chinese, Indians and negroes are given the right of suffrage. ... We oppose the privilege of voting being extended to negroes, Indians and Chinese, at least until the industrious white citizens of Utah are given a State Government. Utah should have been admitted fifteen years ago!

Freeman noted to the reader that “the polygamists of the inferior races are being shipped into America by tens of thousands, and whom the Republicans are trying so streneously [sic] to have admitted to full citizen-ship in all the States, regardless of the will of the people of those States. . . . The Mexican Greasers, barbarians of Russian America [Alaska], Chinese, Indians and Negroes and all inferior races . . . .” He noted that the Mormons were supplying Green River with bread, meat, vegetables and fruit. “Lastly, we favor white men of all nationalities and believe in keeping all inferior races in their respective spheres, as God Almighty originally created them.”

On August 18th, the Index reported that one of the Union Pacific’s grading contractors—who were usually far ahead of the track-layers—was setting off “heavy blasts at the rock cut five miles east” of Green River and that the tracks would reach the town in about 30 days.

The Freemans loathed Pennsylvania Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, a leading opponent of slavery in Congress before the Civil War and a fierce advocate of civil rights for former slaves during Reconstruction. After Stevens died on August 11th, the Index issued forth a “Glory to God in the highest. Death is victorious over the leader of the enemies of the white race.” Stevens’ “carcass,” the newspaper noted, was escorted from Washington to Lancaster, Pa., by an African American military company in the District of Columbia with only four white men in the funeral train—and “they were white only on the outside.”

The Freemans never hesitated to praise their own work. On September 8th Legh wrote that the Index “is eagerly sought for by our whole community. It is looked upon as the only outspoken, independent people’s organ in the Territory, and is admired by all parties for its anti-military Democratic bravery.” The paper’s influence, however, probably didn’t match its rhetoric.

The Index strongly supported Gen. John B. S. Todd of Ft. Randall, Dakota Territory in his race for Dakota’s delegate to Congress that fall. Todd was a cousin of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of President Lincoln. “None but enemies of the white race will vote for any one but Todd,” the paper noted, predicting he would badly beat the two leading candidates, Republican-independent Walter Burleigh and Republican Solomon Spink, both of whom the Index called “mongrels.” Spink came to Green River to campaign, but, according to the Index, “Stink or slink, the riptail wrangler and radical roaring rumpite” drank so much while playing billiards that he “lost all his oratory.” In the end, Spink won the election by a large margin.

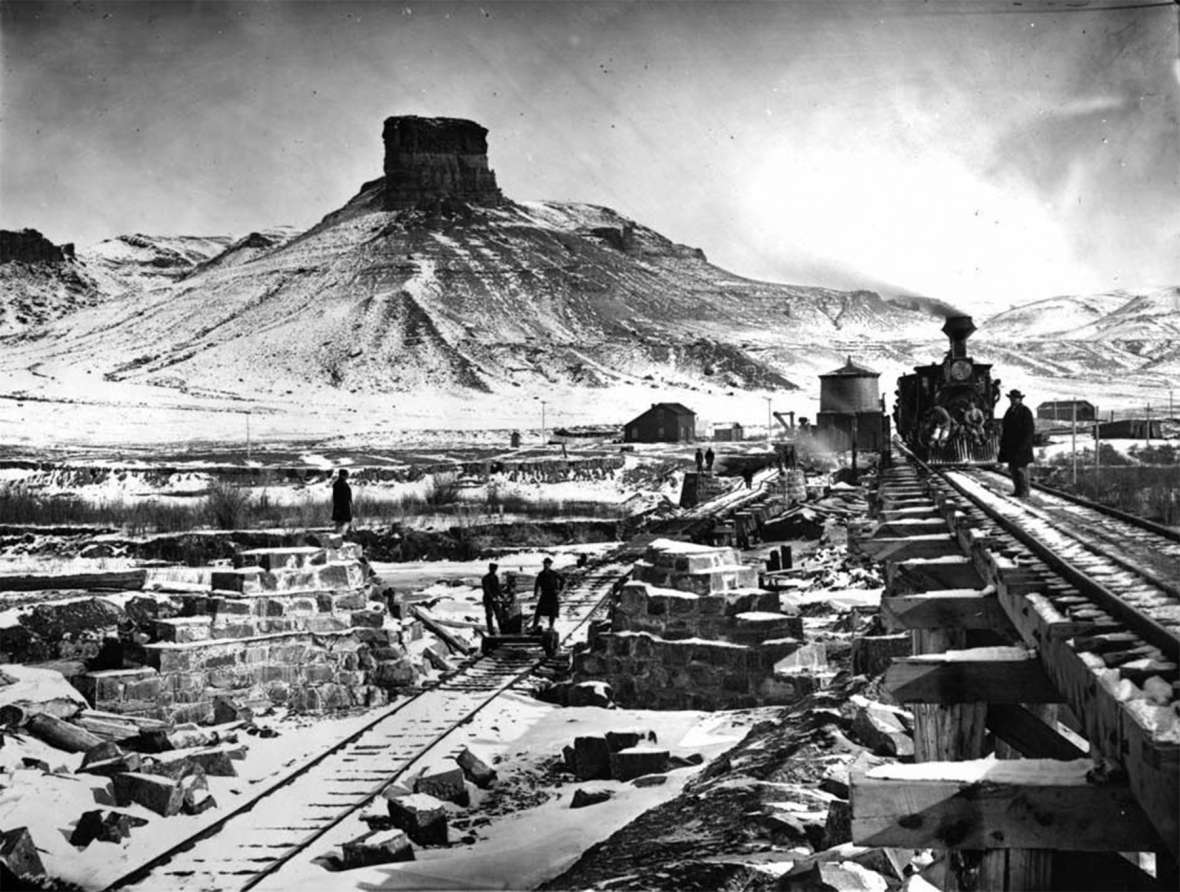

On October 6 the Union Pacific tracks reached Green River City. As the editor looked eastward “we saw the breath ascending from the monster nostrils of the Iron Horse.”

Wild times at Bear River City

By November 3 the Index had moved to Bear River City near present Evanston, Wyo., and immediately began proclaiming that “the town is the greatest success of any founded on the line of the Great National Highway. ... Houses and streets are built up by magic. ... A jail is being built. Great is Bear River.”

In the same issue, the Index reported that somebody went crazy from bad whiskey and opened fire with a pistol in the Southern Restaurant on Uintah Street, severely wounding four men in their legs. It found that “a prize fight in front of our office just after our arrival is another evidence of the progress of civilization.” In short, the paper noted, it was “Times tip top, and prospects bright.”

Publication of the Index, like the town itself, was short-lived, however. On November 10, a group of citizens removed three alleged law-breakers from the jail and hanged them. When accused of being the mob’s leader, Legh Freeman denied it, but still supported the act. “We have never been connected with the vigilantes at any time, though we do heartily endorse their action in ridding our community of a set of creatures who are not worthy of the name of men,” he wrote. A few days later, a mob led by friends of some of those “creatures” put the Index out of business.

Suddenly, everyone moved on ahead to Evanston, and Bear River City quickly disappeared. The run of the Frontier Index in Wyoming was over before Wyoming even was Wyoming, and before the tracks had reached the Utah border.

Legacies

The newspaper’s and the Freemans’ sentiments, therefore, reflect national politics, not local ones, at a time when the nation was divided by the bitter aftermath of war and uncertain about the tasks ahead—especially Reconstruction. There really were little local politics and little law enforcement along the Union Pacific tracks in the future Wyoming in 1867 and 1868 – but crime, vice, dissipation and vigilante action thrived.

Boosterism of local business prospects, however, remained a solid foundation of the Wyoming press well into the 20th century, and a deep skepticism of federal policies runs through the Wyoming press to this day. The Frontier Index’s attitudes on race, however, are another matter. One can hope they are gone forever.

The following May, the Union Pacific met the Central Pacific at Promontory Point, north of Great Salt Lake, and the railroad became truly transcontinental. Real government arrived in Wyoming that same month when the first officials of the new Wyoming Territory, appointed by President Grant, arrived in Cheyenne. Politics began that summer; the first territorial election was in September.

Legh retreated to Culpeper, Va., and earned some money giving a lecture on his experiences in the West. He was married a few days after the lecture and took his bride back to Rock Island, Ill, where he had been held as a prisoner of war. There, he worked again as a telegraph operator. Census records show him living in Indianapolis in 1870. He came west again after that and published a semi-weekly newspaper, the Ogden Freeman from 1875-79.

On Aug. 26, 1879, the Weekly Miner in Butte, Montana Territory, reported that Legh’s wife, Ada Freeman, also of Virginia, died when a “gun dropped from its fastenings” and shot her in the midst of their four young children as the family was moving from Ogden to Butte, to participate in the mining economy there.

Legh died in 1915 in North Yakima, Wash. Fred followed in 1928 and is buried in Athens, Ga.

Editor’s note: WyoHistory.org thanks the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming for support that made publication of this article possible.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Chaplin, W. E. “Some of the Early Newspapers of Wyoming.” Wyoming Historical Society Miscellanies. Laramie Republican, 1919.

- Coutant, C. G. The History of Wyoming Vol. 1, Laramie, Wyo.: Chaplin, Spafford & Mathison, 1899.

- Freeman, Legh. Letter to Wyoming Historian C. G. Coutant. April 1887 University of Wyoming Chisum Collection, Coe Library.

- Frontier Index, 1868: April 21 p. 2; June 9 p. 3; June 16 p. 3; June 26 p. 2; July 7 p. 3; Aug. 11 p. 1, 2; Aug. 18 p. 3; Sept. 8 p. 1; Sept. 18 p. 2; Sept. 22 p. 2; Oct. 6 p. 2; Nov. 3 p. 2.

Secondary Sources

- Brumbaugh, Thomas B. “Fort Laramie Hijinks.” Annals of Wyoming 58 no. 2 (Fall 1986): 4-9.

- Heuterman, Thomas H. Movable Type: Biography of Legh Freeman. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1979. Includes an extensive bibliography.

- ______________. “Assessing the ‘Press on Wheels’: Individualism in Frontier Journalism.” Journalism Quarterly Fall 1976: 423-428. Joseph Jacobucci collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

- Lent, John A. “The Press on Wheels: A History of the Frontier Index of Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Elsewhere?” Annals of Wyoming 43, no. 2 (Fall 1971): 165-204.

- McMurtrie, Douglas C. “Pioneer Printing in Wyoming” Annals of Wyoming 9 (January 1933): 729-42.

- “The Sweetwater Mines, A Pioneer Wyoming Newspaper.” Journalism Quarterly 12 (June 1935): 164-65.

- Tate, Michael L. The Frontier Army in the Settlement of the West Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

- Thompson, Claudia. “Driven from Point to Point: Fact and Legend of the Bear River Riot.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 46, no. 4 (Winter 1996): 24-37.

Illustrations

- The photo of the Washington hand press is from the Henry Ford museum. Used with thanks.

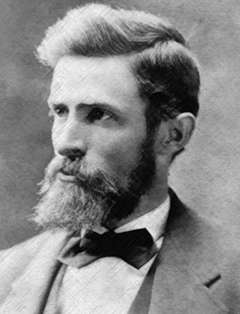

- The photos of Legh Freeman and his wife, Ada Freeman, are from glendalemt.com. Used with thanks.

- The image of the Index’s motto is from Wyoming Newspapers. Used with thanks.

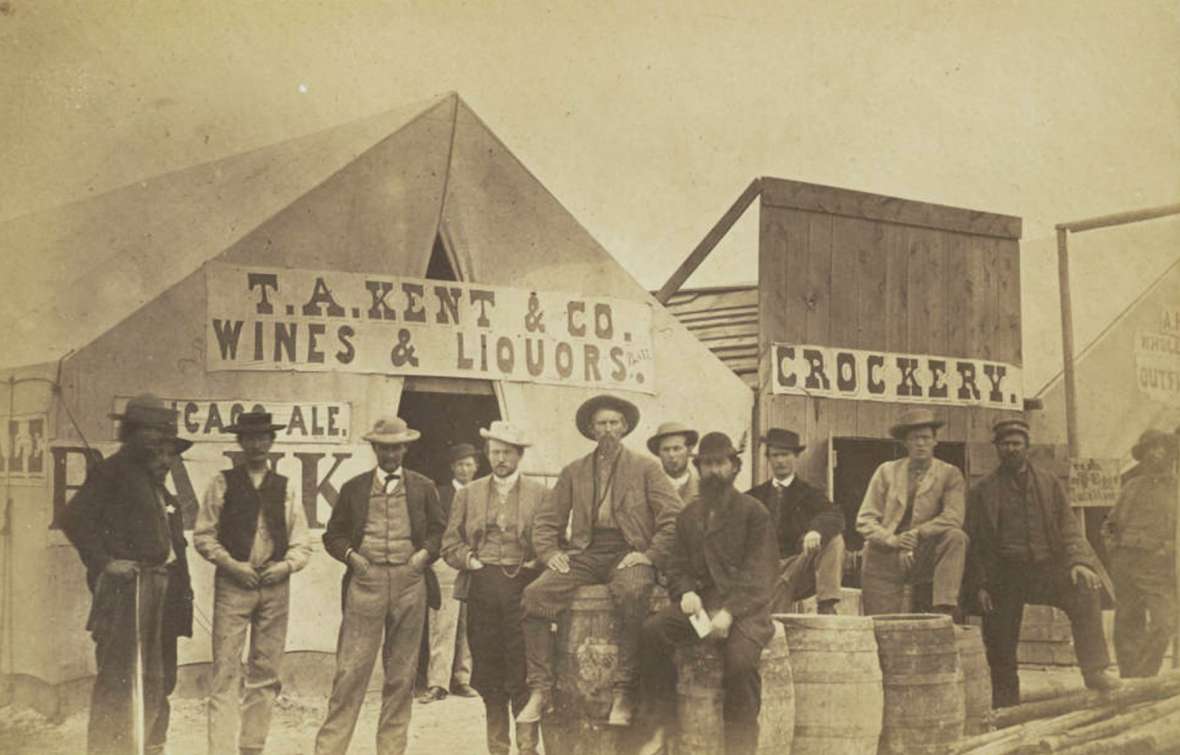

- A.C. Hull’s photo of Benton in 1868 is from the western history collections at the Denver Public Library. Used with thanks.

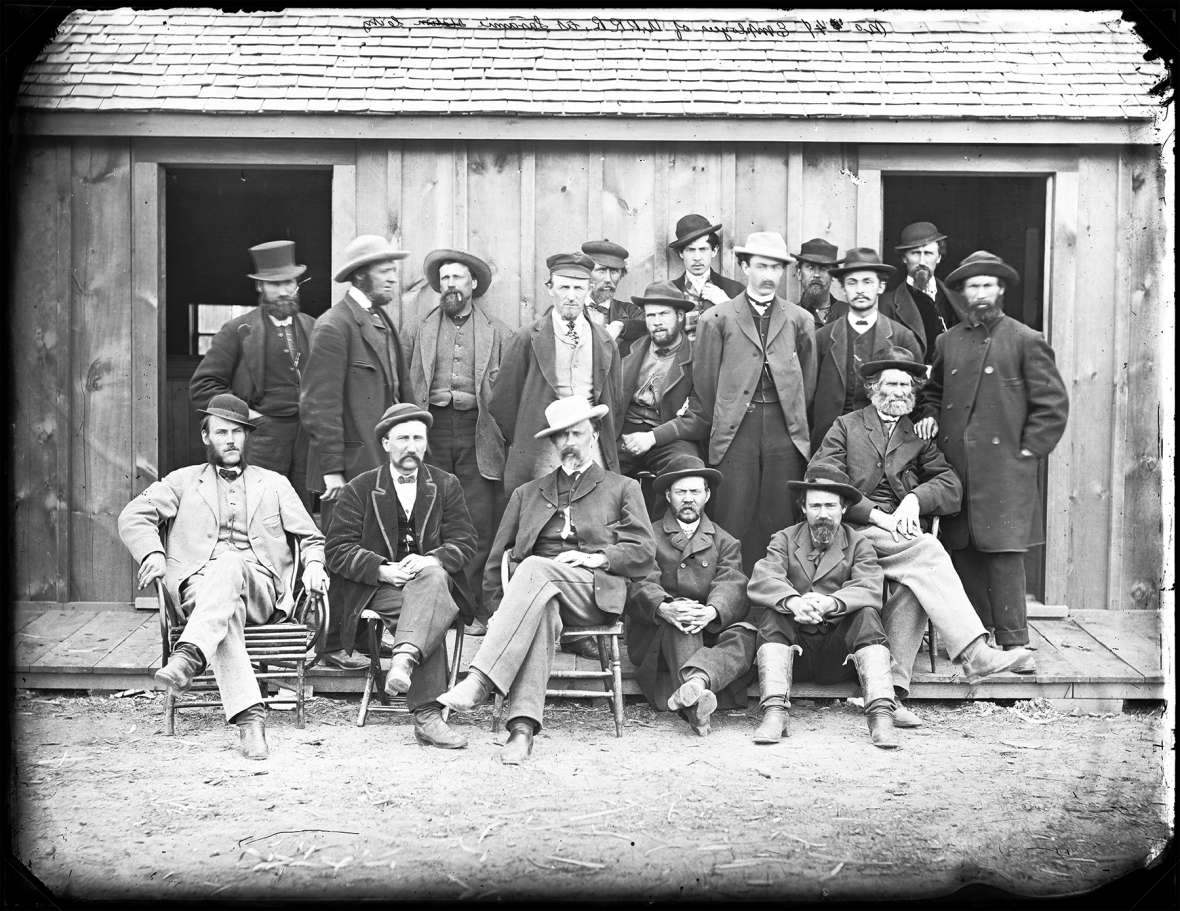

- The photos of Bear River City, the locomotive and Bridges at Green River City and the the Union Pacific employees at Laramie are all from the Andrew J. Russell collections at the Oakland Museum of California. Used with thanks.