- Home

- Encyclopedia

- John E. Osborne and The Logjammed Politics of 1893

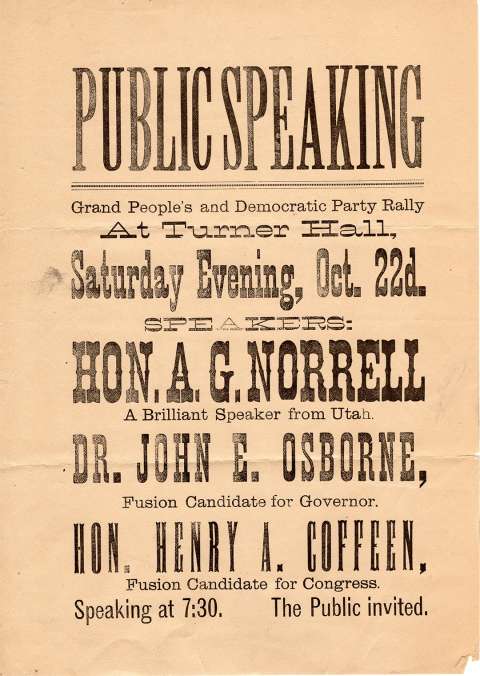

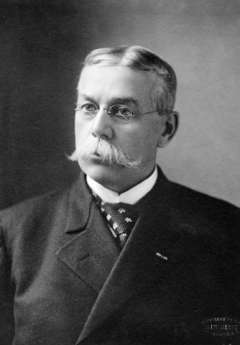

John E. Osborne and the Logjammed Politics of 1893

In December 1892, a tug-of-war between Wyoming Democrats and Republicans resulted in a tense standoff in the governor’s office. Two men claimed to be the state’s top official. The deep-seated conflict carried over into the state’s legislative session. The divide between lawmakers that year was so great that they failed to elect a U.S. Senator, leaving Wyoming with only one senator for the next two years.

The effects of the Johnson County War the previous April, when vigilantes invaded Johnson County and murdered two men in an ill-fated attempt to put a stop to cattle rustling, still resonated with the public. The events occurred in the spring, but became the significant issue during the fall campaign. Would that conflict and its aftermath lead to violence in the capital city?

A Dec. 6, 1892, report in the Cheyenne Daily Sun showed the strain:

No proclamations yesterday. Armed men on both sides of the big hallway at the state house. Armed men in the ‘office’ of the pseudo governor. Armed men with Private Secretary Repath in the office of the acting governor. Armed men with Chief Clerk Meldrum in the office of the secretary of state. No trouble. No sign of trouble. No loud talking. Plenty of quiet, earnest consultation.

Democrat John E. Osborne of Rawlins, elected on Nov. 8, 1892, to fill the vacancy in the office created when the first elected governor of Wyoming, Francis E. Warren, resigned to become U.S. Senator, engaged a notary public to give him the oath of office on Dec. 2, 1892. Osborne issued a proclamation that he was now the governor and set up shop in the governor’s office.

However, Acting Governor Amos W. Barber, a Republican, who had been ill that day, issued a proclamation on December 3 asserting that Osborne had “by stealth and force effected an entrance into the capitol building at Cheyenne” and had attempted to declare himself elected and assume the powers of the office of governor, in “direct violation of the constitution and laws of the state.” Barber, as secretary of state, had become the acting governor in 1890, when Warren resigned from the position.

The Sun reported that Osborne had snuck into the office through a window that had been forced open. Modern-day historians doubt the likelihood of this version of events, attributing it to Republican propaganda. Osborne, the Republican-leaning Sun stated, had been “provided with a pistol and ammunition,” and Barber had allowed a bed to be taken in to him.

Barber’s private secretary, R.H. Repath, made sure the office remained locked and kept the keys. The crowd that night “swelled to enormous proportions,” according to the Sun, and officials and lawmen remained on hand. But by 2 a.m., the “scene wore a decidedly peaceful aspect.”

Post-invasion politics

Violence did not break out in Cheyenne, but the Johnson County War continued to generate newspaper headlines because the trial of the invaders was yet to be scheduled. And in 1892 and 1893, the political stakes were high.

The invasion was “the major issue in the 1892 election,” according to historian T.A. Larson, and while it “was not a Republican project,” he explains, “many citizens associated the big cattlemen with the Republican party.” Democratic newspapers often referred to “The Republican Ring Gang of Cattle Barons of Cheyenne.”

That perception certainly plagued Sen. Warren, whose term would expire in March 1893. He wanted to continue representing Wyoming in Washington, but his arid-lands bill had also been a campaign issue in the state, where Democrats opposed a policy they felt would “permit a ‘land steal’ by large corporations,” according to Larson.

Republican U.S. Sen. Joseph Carey’s term would not expire until 1895. Osborne, a Democrat, could sway members of the Legislature to elect a Democrat to Warren’s senatorial post, especially likely if the Legislature contained more Democrats than Republicans. During the campaign, Democrats had “fused” with Populists, at that time reaching the peak of their power across the nation. Populists supported the free coinage of silver and the interests of small farmers and opposed the power of banks and railroads. Although the Populists weren’t a large force in Wyoming politics, there were enough in the Legislature to make a significant difference that year.

In his book Wyoming Range War, historian and attorney John W. Davis states that the “most important responsibility” of the Legislature was to elect a U.S. Senator, but writes, “As noble as the prize might be, the attempts to obtain it were correspondingly ignoble.” Davis explains, “The effort to select a Wyoming senator in 1893 was a travesty, surely one of the lowest points in the state’s political history. The Republicans did everything they could to undercut the selection of a senator, but they would never have succeeded without the thoroughgoing political incompetence of the Democrats and Populists.”

Distrust, delays and decisions

Osborne originally hailed from Vermont and, after earning his medical degree at the University of Vermont, came to Rawlins in 1881 as a Union Pacific surgeon and practiced with local physician Thomas Maghee. A couple of years later, Osborne had been elected to the Territorial Assembly but did not serve because he had to leave the territory. He did serve as Rawlins’ mayor in 1888 after being elected to that position.

He owned a pharmacy and raised sheep, as well as participating in other businesses, and these enterprises made him wealthy. In July 1892, delegates to the contentious Democratic convention in Rock Springs, Wyo., finally chose him as their nominee for governor on the 37th ballot. At one point, he had withdrawn his name, but delegates convinced him to stay the course. The party platform condemned the actions of the invaders of Johnson County and supported the policy of fusion with Populists.

During the campaign, Osborne traveled thousands of miles throughout the state by buckboard. He defeated Laramie banker Edward Ivinson, a Republican, in the November 1892, election by a vote of 9,290 to 7,509. Wyoming historian Phil Roberts says, “Ivinson did not have the taint of Warren’s operations nor was he close to Carey and apparently believed that he would be able to escape ‘punishment’ in the polls by those facts.” But it did not work that way.

Osborne attempted to assume the duties of governor a month before the constitutionally set time—the first Monday in January following a general election—because Democrats were concerned that Republicans would try to sway election results in their favor so that the Legislature would elect Warren to another term as U.S. Senator. Osborne argued that no state canvassing board was authorized to decide the gubernatorial election and the county canvassing boards showed that he had been elected to the office and was “duly qualified,” and thus, could take office. He accused Amos Barber of being guilty of usurpation of the office.

But as historian Larson notes, Osborne “had a comic-opera time of it.” Legal haggling continued during the months of November and December 1892, and the questions soon came before the Wyoming Supreme Court. Among them were concerns about the assumption of offices after special elections held to fill vacancies—as opposed to after general elections—and the accuracy of decisions by canvassing boards. Attorney Willis Van Devanter, as the state chairman of the Republican Party and an ally of Warren’s, interceded in county canvasses that had questionable results and could affect the political balance of the Legislature. According to historian Lewis Gould, Van Devanter’s plan was to “make the opposition decidedly weary” of all the litigation.

Races were contested in Converse, Fremont and Carbon counties. In Carbon County, the Hanna returns stood out: The precinct was not listed and the polling list had not been signed. If the clerk did not accept the returns, two Democrats would not be elected to the House. Republican County Clerk S.B. Ross canvassed the returns with two justices of the peace, one Republican and one Democrat. They voted two to one accept the Hanna returns. Van Devanter, though, argued that the clerk should have more power than the other two men on the board.

A vote canvass and an appeal

Osborne set Dec. 5, 1892, as the date that a state canvassing board would convene to review all the county votes, but when he arrived at the secretary of state’s office, the doors were locked. The other members of the state canvassing board of officers elected by voters statewide—state auditor, state treasurer and secretary of state—were all Republicans. Acting Governor Barber was also acting as secretary of state in this capacity, and Democrats distrusted him and viewed him as a sympathizer with the Johnson County invaders. He had set a Dec. 8, 1892, date for the canvass.

On that day, members of all three parties—Republicans, Democrats and Populists—were present. Davis writes, “The all-Republican canvassing board accepted every one of Willis Van Devanter’s arguments; the only delay was so that the board was sure of getting Francis Warren’s instructions right.” The board accepted the Carbon County results without the Hanna returns included and ruled that only Acting Governor Barber could issue certificates of election—something that the Democrats had hoped to avoid by having Osborne assume the gubernatorial position.

The Democrats sought a ruling by the Wyoming Supreme Court, which took the case on an expedited basis. Justices listened to oral arguments in mid-December and issued a decision on Dec. 31, 1892. The all-Republican court gave equal power to the three men on the Carbon County canvassing board and allowed the Hanna returns to be included in the final count. Democrats S.B. Bennett and Harry Chapman were elected to the House from Carbon County.

In the decision the justices noted, “The rights of the people in choosing their officers are certainly safer in the hands of three persons, of different political parties when practicable, than in the hands of one man.” The other questionable elections—in Converse and Fremont counties—the court left to the Legislature to decide.

Acting Governor Amos W. Barber issued a pardon to state penitentiary inmate James Moore on Dec. 28, 1892. The question of its validity brought another case before the Wyoming Supreme Court.

An unusual inauguration

John E. Osborne’s Jan. 2, 1893, inauguration was “exceedingly unostentatious,” according to a report in the Cheyenne Daily Sun. Osborne named Democrat Charles P. Hill, a Rawlins attorney, as his private secretary. Hill had been one of the men who served on the Carbon County canvassing board. The Leader reported that Barber officially transferred the office to Osborne at 2 p.m.

While the inaugural formalities were perhaps simple in nature and the newspaper articles did not mention his attire, Osborne apparently wore shoes made from the skin of outlaw Big Nose George, who had been lynched in Rawlins in 1881 after murdering a deputy. Osborne and another local physician, Thomas Maghee, had claimed the outlaw’s body for medical study and skinned the corpse, giving the skullcap to Maghee’s young protégée, Lillian Heath. Osborne had the shoes and a medical bag made from the hide.

The Wyoming Supreme Court ruled on Jan. 17, 1893, that Osborne’s attempt to assume his official duties in December was “premature and invalid.” The pardon of James Moore, which had been issued by Acting Governor Barber, was deemed valid and Moore was set free. The justices debated various constitutional issues including the timing of the governor taking office after an election, whether a special or general election, and the determination of the state canvassing board.

The men who decided the case—Herman V.S. Groesbeck, chief justice; Asbury B. Conaway, associate justice; and Jesse Knight, district judge of the Third Judicial District—were all Republicans. Conaway and Knight had served as members of the Constitutional Convention in 1889. The justices asked Knight to hear the case and help determine the outcome because newly elected Justice Gibson Clark, a Democrat, whose term began in January 1893, had excused himself. He had been nominated for the court at the Democratic convention when John Osborne was nominated as a gubernatorial candidate, and he had served as attorney for A.L. New, the state Democratic chairman.

Second Wyoming Legislature: “a dismal failure”

After this inauspicious start, Osborne, a bachelor who was in his early 30s and acknowledged as the nation’s youngest governor in some press reports, endured a term with a deadlocked legislature. The members decided the Converse and Fremont county races in favor of the Democrats. State Sen. John N. Tisdale, Johnson County Republican, Johnson County invader and by now a resident of Salt Lake City, was removed by a majority vote. The Legislature now totaled 48: Republicans 22, Democrats 21 and Populists 5.

The legislative session was, according to historian Gould, “bitter, faction-ridden and indecisive.” Thirty-one attempts to elect a U.S. Senator failed. Warren realized early on that the votes were too fragmented for him to win the seat. During one ballot, Democrat John Charles Thompson, Sr., a Cheyenne attorney fell one vote short of earning election. Democrats accused Republicans of bribing the man who refused to vote for Thompson. Other “intrigues” occurred, including the alleged poisoning of a Sen. James Kime’s cocktail—he sickened, but did not die—and the censure of Sen. L. Kabis, accused of tampering with the drink.

Gov. Osborne decided not to attend the inauguration of President Grover Cleveland in Washington, D.C., a Democrat, because Republican Amos Barber, who had returned to his original position as Wyoming’s secretary of state, would again serve as acting governor during Osborne’s absence. The risk that Barber might appoint a Republican to the Senate was too great for Osborne feel safe leaving the state.

The Democratic Cheyenne Daily Leader labeled the state’s second legislative session “a dismal failure.” A bill to eliminate the Wyoming Live Stock Commission did not pass, and $23,000 appropriated by the senators for prosecution expenses for the trial of the cattlemen did not reach the House before its adjournment, so that did not become law either. However, Osborne used his veto power to strike down a $12,000 appropriation for the Wyoming Live Stock Commission, which angered cattlemen “offended by suffering real consequences for their actions,” according to Davis.

Two years without a senator

A few days after the Wyoming legislative session ended, Osborne, under the powers granted him by the state’s constitution, appointed a Democrat, A.C. Beckwith to the U.S. Senate. Gould explains that Osborne thus hoped to placate A.L. New, state Democratic Party chairman, who had sought the seat, and John Charles Thompson, who had come near to being elected.

The U.S. Senate met in special session in March that year, but tabled a resolution that would have begun the confirmation process. Historian Gould explains, “The Senate questioned the power of a governor to fill a vacancy left by the failure of the legislature to act, and Beckwith’s case, like that of several other senators appointed from western states, was referred to a committee for investigation.”

After several months without action taken, Beckwith submitted his resignation in July 1893, apparently mostly over patronage issues with New. New convinced Osborne to appoint him, but the governor was understandably reluctant to call a special joint session of the Wyoming Legislature to decide the matter.

According to the 1974 edition of the Wyoming Blue Book, the U.S. Senate convened in regular session in early August, and Beckwith’s resignation was received before the resolution about his appointment was to be considered. Had the resignation not been submitted before the resolution, the Senate might have confirmed Beckwith. Instead, during the years 1893-1895, Wyoming had only one U.S. senator, Joseph Carey, instead of the two allowed for the state.

Osborne’s later political career

In 1896, Osborne declined the nomination for governor, accepting instead the opportunity to run for Congress. He won, defeating Republican Frank W. Mondell by just 266 votes. In 1897-1899, Osborne served as Wyoming’s lone congressional representative with Republican U.S. senators Francis E. Warren and Clarence D. Clark.

In 1898, Osborne tried for a U.S. Senate seat, but lost to Clark. Warren and Clark continued to represent Wyoming in that capacity.

However, Osborne remained active in politics on the national level for many years. From 1900 to 1920, he served as a member of the Democratic National Committee. He enjoyed traveling and while visiting the eastern Mediterranean in 1906, he met Selina Smith of Princeton, Ky., and was immediately smitten.

On his passport application the previous year, he had listed his date of birth as June 19, 1860, although many sources report he was born in 1858. She was more than 20 years younger than he, but they were engaged soon after they met.

They were married Nov. 2, 1907, at Selina’s parents’ house. They honeymooned in New York, Tahiti and Denver before returning to Rawlins. The couple had a daughter, Jean Curtis, in 1908.

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Osborne as first assistant secretary of state under William Jennings Bryan, a longtime friend of Osborne’s. Bryan resigned in 1915 because he disagreed with Wilson’s war policy. Osborne served until December 1915.

In 1918, Osborne once again ran for the U.S. Senate against Francis E. Warren. By this time, the U.S. Constitution had been amended to allow voters rather than state legislators to choose senators. Historian Hugh Ridenour explains that Warren, 75, had planned to retire, but when two Republican candidates, John W. Hay and Frank Mondell, campaigned extensively and then decided Warren’s experience was needed instead, Warren entered the race and they withdrew.

Democrats nominated Osborne. Ridenour states the campaign was “typically acrimonious” and Republicans hounded Osborne about his premature attempt to become Wyoming’s governor in 1892. Osborne lost by more than 6,400 votes.

Traveling and business interests in Rawlins kept Osborne busy after that. Selina Osborne died March 2, 1942, at 59. John Osborne died April 24, 1943, in Rawlins, after having suffered a heart attack. He had served for many years as chairman of the board of the Rawlins National Bank, which closed for a half day to honor him when his funeral was held. Both Osborne and his wife were buried in the family mausoleum in Cedar Hill Cemetery in Princeton, Ky. Their daughter died in 1951.

Osborne had served as Wyoming’s top officer during one of its most tumultuous and least productive legislative terms. His eagerness to take the gubernatorial office is perhaps the most remembered aspect of his political career, but despite that controversial move, he continued to represent the state on the national level in highly respected positions for many years.

Resources

Primary sources

- Newspapers found at Wyoming Newspapers online:

Carbon County Journal, “Governor Osborne.” Dec. 10, 1892, 3.

Carbon County Journal, “The Winners Named,” July 30, 1892, 2.

Cheyenne Daily Sun, “Has Been No Change,” Dec. 6, 1892, 3.

Cheyenne Daily Sun, “Usurpation--John E. Osborne Boldly Attempts to Seize the Office of Governor,” Dec. 3, 1892, 3.

Cheyenne Daily Sun, “Pretender on Deck,” Dec. 4, 1892, 3.

Cheyenne Daily Sun, “As Ordained at the Polls” Jan. 3, 1893, 3.

Cheyenne Daily Leader, “Under Difficulty—Conversations Carried on Through a Door,” Dec. 6, 1892, 3.

Cheyenne Daily Leader, “Again Inaugurated,” Jan. 3, 1893, 3.

Cheyenne Daily Leader, “Peculiar Conduct, “Jan. 3, 1893, 2.

Cheyenne Daily Leader, Feb. 19, 1893, “End of the Session,” 2.

Above listed newspapers found at Wyoming Newspapers. Accessed throughout January 2016, at http://newspapers.wyo.gov.) - “Dr. John E. Osborne Buried This Morning,” Carbon County News, April 29, 1943.

- “Dr. John E. Osborne Dies in Memorial Hospital,” Rawlins Republican-Bulletin, April 27, 1943.

- Hill, C. P. Public Papers, Messages and Proclamations of Hon. John E. Osborne, Governor of Wyoming 1893-4, Together with Some Public Addresses and Correspondence of Interest. Cheyenne: 1894. Osborne Collection, Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyo.

- House Journal of the State Legislature of Wyoming. 1899, 119. Accessed Jan. 26, 2106, at https://books.google.com.

- “In Memoriam—John Eugene Osborne 1858-1943.” Annals of Wyoming 15, no. 3, (July 1943), 279-280. Accessed Jan. 23, 2016, at https://archive.org/details/annalsofwyom15141943wyom.

- “Mrs. John E. Osborne Dies in Kentucky,” Rawlins Republican-Bulletin, March 4, 1942.

- McBride, J.F. “John E. Osborne, Governor of Wyoming.” Typewritten manuscript, 1894. Osborne Collection, Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyo.

- Osborne Collection, Carbon County Museum. Collection includes a massive 200-page scrapbook filled with newspaper clippings about Osborne’s political career, the shoes, the brand, medical items, a desk and a curio cabinet as well as some correspondence and photographs.

- U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for John E. Osborne, from Ancestry.com. Application No. 97972, dated Jan. 30, 1905. Osborne Collection, Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyo.

- Wyoming Constitution, Art. 6, Sec. 17. “Time of holding general and special elections; when elected officers to enter upon duties.” Accessed Jan. 26, 2016, at http://www.uwyo.edu/robertshistory/wyoming_constitution_full_text.htm.

- _________________, Art. 6, Sec. 16. “When officers to hold over; suspension of officers.” Accessed Jan. 26, 2016, at http://www.uwyo.edu/robertshistory/wyoming_constitution_full_text.htm.

- Wyoming Reports, In Re Moore 1892, 113. Accessed Jan. 14, 2016, at https://books.google.com.

- Wyoming Reports, State ex rel Bennett v. Barber 1892, 78. Accessed Jan. 23, 2016, at https://books.google.com.

Secondary sources

- Davis, John W. Wyoming Range War. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010, 227-246, 255-270.

- Drake, Kerry. Francis E. Warren: A Massachusetts Farm Boy Who Changed Wyoming. WyoHistory.org. Accessed Jan. 20, 2016, at /essays/francis-e-warren-massachusetts-farm-boy-who-changed-wyoming.

- Find a Grave. “John Eugene Osborne.” Accessed Jan. 14, 2016, at http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Osborne&GSfn=John&GSbyrel=all&GSdy=1943&GSdyrel=in&GSob=n&GRid=7182235&df=all&.

- Georgen, Cynde. John B. Kendrick: Cowboy, Cattle King, Governor and U.S. Senator. WyoHistory.org. Accessed Jan. 20, 2016, at /encyclopedia/john-kendrick.

- Gould, Lewis. Wyoming: A Political History 1868-1896. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1968, 159-196.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming, 2d ed., rev. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1978. 284-290.

- Ridenour, Hugh. “John E. Osborne: A Real ‘Character’ from the Old West.” Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal, Summer 2008, 2-16.

- Roberts, Phil. University of Wyoming history professor. Email to author, Jan. 18, 2016.

- Trenholm, Virginia Cole, ed. Wyoming Blue Book, vol. 2. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming State Archives and Historical Department, 1974.

- Van Pelt, Lori. Big Nose George: A Grisly Frontier Tale. WyoHistory.org. Accessed Jan. 20, 2016, at /encyclopedia/big-nose-george-grisly-frontier-tale.

- ___________. Dreamers and Schemers: Profiles from Carbon County, Wyoming’s Past. Glendo, Wyo.: High Plains Press, 1999, 113-120.

- ___________. Lillian Heath: Wyoming’s First Female Physician Packed a Pistol. WyoHistory.org. Accessed Jan. 20, 2016, at /encyclopedia/lillian-heath.

- ___________. Willis Van Devanter: Cheyenne Lawyer and U.S. Supreme Court Justice. WyoHistory.org. Accessed Jan. 20, 2016, at /encyclopedia/willis-van-devanter-cheyenne-lawyer-and-us-supreme-court-justice.

- Wyoming State Archives. John Osborne. WyoHistory.org. /encyclopedia/john-osborne.

- ____________________. Wyoming Postscripts. “Wyoming’s Bachelor Governor: Dr. John E. Osborne.” June 19, 2015. Accessed Jan. 15, 2016, at https://wyostatearchives.wordpress.com/2015/06/19/wyomings-bachelor-governor-dr-john-e-osborne/.

Field Trips

The shoes John Osborne wore when he was inaugurated as Wyoming’s governor are displayed today at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins near his livestock brand—the skull and crossbones. For many years, he had displayed the shoes in a glass case in the lobby of the Rawlins National Bank. A massive 200-page scrapbook kept in the museum collections contains numerous newspaper articles about his political career. His private secretary, C.P. Hill, compiled many of Osborne’s proclamations and messages as governor into a book, which is also part of the museum collections. See below for details on visiting the museum.

Illustrations

- The photos of Francis E. Warren and Selina Smith Osborne are from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The rest of the photos are from the collections of the Carbon County Museum. Used with permission and thanks. Museum Registrar Corinne Gordon advises us that though Osborne’s auto was often claimed to be first one in Rawlins, that was not the case. The former governor was the first in Rawlins to order a car, and local newspapers reported his order. But the factory burnt down, shipment was delayed and a different auto arrived in town first. That car, however, did not work well. Osborne’s was the first car in good working order in Rawlins, thanks, says Gordon, to mechanic D.C. Kinnaman.