- Home

- Encyclopedia

- High School Hair Wars: 1960s Casper Board Suspe...

High School Hair Wars: 1960s Casper board suspends boy’s education

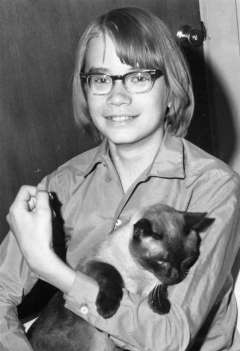

In September 1967, a ninth-grade boy at Dean Morgan Junior High School in Casper, Wyo. was suspended for refusing to cut his hair to the length required by the Casper-Midwest School Board. Loren Evans, then 14, did not attend school for the next three years.

Nationally, the parents of other long-haired students were taking schools to court. However, since Evans’s widowed mother did not, the issue never became a court fight; Wyoming’s compulsory education law allowed students to leave school after eighth grade.

Evanses meet with the school board

About three weeks after Evans was suspended, the Oct. 17, 1967, Casper Star-Tribune reported that at the recent school board meeting, “A mother defended her 14-year-old son’s refusal to have his nearly shoulder length hair cut as required by school rules.”

“His hair is his declaration of independence,” stated Mrs. Mary Evans. “He will not give it up. I will not force him to.”

At this meeting, Kelly Walsh, the school district’s assistant superintendent, told the board “that the boy was neat, clean, and well-behaved.” Walsh also commented that the length of Evans’s hair wasn’t as important as his defiance of the principal and school rules. That would lead to anarchy, Walsh said.

About five weeks after the board meeting, the Star-Tribune published an article focusing on Mrs. Evans and her son, noting that despite his absence from school, his education was progressing. “We can’t keep up with trips to the library,” Mary Evans noted. Loren “reads almost anything,” including college-level books. He focused especially on science, history and philosophy. Mrs. Evans had few concerns about college, commenting that “We just have to find the right school. … If he can pass the college boards he won’t have trouble getting into college.” All of her five older children graduated from college, earning associate’s, bachelor’s or master’s degrees.

Comments come in from around the state

About a year and a half later, on March 5, 1969, the Star-Tribune reported that Mrs. Evans asked the school board to discuss with her a Feb. 20, 1969, ruling by James E. Doyle, federal judge of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin. Doyle upheld the right of two Williams Bay, Wisc., students to attend school with long hair.

During that time, many more boys and men across the United States—though less so in Wyoming—began wearing their hair longer. In more important ways, too, the nation was changing fast. Fierce fighting in the Tet Offensive in Vietnam in January and February 1968 swung U.S. public opinion more and more strongly against the war there. Martin Luther King, Jr., was murdered that April and Robert Kennedy was murdered in June. In August 1968, violence at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago brought images to Wyoming television screens of helmeted police clubbing long-haired male protesters to the ground. On the Olympics podium in October in Mexico City, African-American gold- and bronze-medalist sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised gloved fists when the Star-Spangled Banner was played.

In the three weeks between Mrs. Evans’s request and the board meeting, the Star-Tribune published 11 letters to the editor, eight supporting the existing policy and three supporting the Evanses.

“If your school has rules, stick up for your school because if you don’t even if you win this round your child will be damaged,” wrote Mrs. Paul Baker of Moorcroft, Wyo. “I feel so sorry for these young people that their parents allow all this permissiveness,” Baker continued, “the child … want[s] authority.”

Emma Fillerup of Thermopolis, Wyo., implied that Mrs. Evans was the problem: “I would like to state Mrs. Evans should ask herself if she isn’t using her son to flaunt her own disregard for authority.”

Readers on the other side were just as outspoken. Dyan Talkington of Casper wrote, “Conformity is stupid beyond compare. When a person lives in a society of cripples, should he sever a limb in order to be like the others? The fact that so many Casperites become irate because of a trivial matter is appalling.”

“Instead of finding America a people with ‘well-rounded and open minds,’” wrote Steven R. Gunderson, referring to an earlier letter to the editor, “Loren Evans will find hate and persecution because of his … long hair. If you wish to see the real America, be a black man or grow your hair long.”

The board keeps the rule

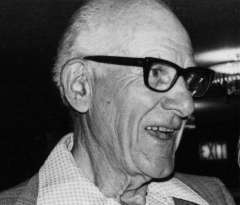

On Monday, March 24, 1969, the school board met with Loren Evans and his mother to consider Mrs. Evans’s request that the board suspend all rules related to personal appearance except those prohibiting lewdness and extreme uncleanliness. Two days later the Star-Tribune reported, “The board showed little sign of sympathy to her request.”

At this meeting, when board President Dr. Nathaniel E. Fowler asked Loren his opinion of the rules, Evans replied, “I think that if I want to wear something that is not considered obscene, I have a right to. In a public-school system using government money, you don’t really have a right to tell me what I should dress like and look like.”

On April 28, 1969, Casper attorney Robert A. Burgess wrote a legal opinion, requested by the school board, on the existing hair-grooming policy. Burgess noted that the Wyoming Education Code granted local school boards the right to set and enforce rules. Therefore, “the requirement of the school is reasonable, and … it has not acted arbitrarily, capriciously or discriminatorily.”

The Star-Tribune reported on May 3 that an unidentified Casper resident had contacted the American Civil Liberties Union in Denver, Colo., on Loren Evans’s behalf. The ACLU had in turn contacted Mrs. Evans. This was one of five times the Star-Tribune reported over the next six months that the ACLU might advocate for Evans, but apparently the ACLU took no action.

UW faculty and students support Evans

Next, the editor of the University of Wyoming’s student newspaper voiced his support for the Evanses. On May 9, 1969, The Branding Iron published an extensive interview with Loren and Mary Evans, plus an editorial, “The Making of Automatons.” In his interview article, editor Phil White mentioned events apparently not reported so far.

“The case of Loren Evans has a long history sprinkled with harassing phone calls and letters,” White wrote, quoting from an example, “Dear Miss Loren Evans … I’ll be darned if you don’t look feminine. My odium for long, shaggy hair is beyond words to express. Good bye, ‘Cutie.’”

Mrs. Evans told White, “We’ve reached the place where we can laugh at … [the letters] or ignore them. It wasn’t too easy at first.”

In his editorial, White wrote, “If we agree that intolerance is bad … and that hatred of another human being solely because of his hair can be called intolerance, then we submit that the removal of the one with long hair only perpetuates and strengthens intolerance.”

Further support for Evans emerged about two weeks later when the May 23, 1969, Star-Tribune reported that four faculty members and 38 students at the University of Wyoming law school had written to the school board: “We believe the Constitution of the United States protects the right of a person to grow his hair to any length … and not be denied the opportunity to attend public school because of it.”

Star-Tribune articles and letters to the editor continued through early June.

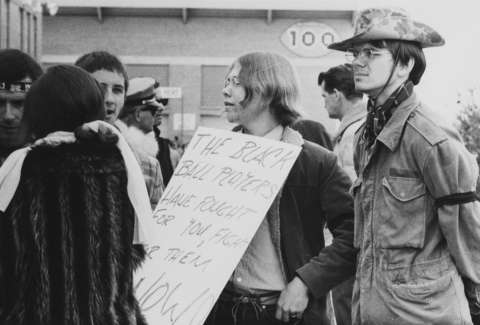

In October, widespread protests over, again, deeper issues came to the University of Wyoming campus. On Oct. 17, UW football coach Lloyd Eaton immediately dismissed 14 black players from the team when they wore black armbands to a meeting with him to discuss how they might protest what they saw as racist policies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints--the Mormons--during the game scheduled the next day against church-owned Brigham Young University. The conflict was covered widely in local and national news sources.

Discussion and reporting on the Loren Evans question in Casper resumed when the October 21, 1969, Star-Tribune wrote, “A group calling itself the Committee to Reinstate Loren Evans … mailed a petition signed by 335 University of Wyoming students to the Casper-Midwest School Board protesting ‘its continued deprivation of a public education to Loren Evans of Evansville.’”

Evans remained out of school; fall 1969 was the beginning of his third year of suspension. In late April 1970, Mary Evans retained a Casper attorney—not affiliated with the ACLU—and this attorney contacted Superintendent of Schools Maurice Griffith.

National unrest, meanwhile, continued to spread. On May 4, 1970, 28 national guardsmen killed four students and wounded nine, on the campus of Kent State University in Kent, Ohio. Two of the mortally wounded students had been taking part in ongoing mass protests against the Vietnam War; the other two had been walking to class.

One year previously, discussing campus turmoil with Phil White, Mary Evans said, “I have felt for these students for so long. People don’t listen to them. People seem to think that young people either can’t feel at all or that their feelings don’t count.”

School board solicits comment

Perhaps responding to the possibility of a lawsuit, the school board held two meetings to discuss the current hair-grooming policy, at which they heard public opinions.

Important information surfaced at the second meeting, on May 25, 1970: Students at Natrona County High School, along with Principal William Reese, reported that hair-length rules were so difficult to enforce that many male students were attending school wearing long hair, sideburns and mustaches.

Reese said that he did not see every student every day, and that teachers were not sending long-haired students to his office. In addition, student council member Dave Kubichek stated, “[L]ong hair on males presents no deterrence to getting a good education,” adding that long hair “was accepted by other students and was no distraction.”

Evans returns to school

On Monday, June 1, 1970, the United States Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal of Wisconsin judge James E. Doyle’s decision, thus letting it stand. About a month later, the July 3, 1970, Star-Tribune reported that the school board had discontinued hair-length restrictions and that Loren Evans would be readmitted to school.

In 1969 and 1970, the Star-Tribune published three editorials supporting the school board, but also noting that Evans was a fine young person, and “undoubtedly … a good, misguided youngster.”

Wyoming and the nation

Other schools around Wyoming also had rules against long hair for boys. In 1969, the Gillette school board’s policy prohibited “extreme hair styles … such as Beatle cuts, duck tails, Mohawks” or those long enough to cover the collar. Two male students were suspended for violating the rule in October of that year. The Cheyenne Central High School hair-grooming code stated that a boy’s hair could not cover his ears, nor sideburns be longer than the bottom of the ear. More than 60 Central High students were suspended for hair and dress code violations in November 1969. At Laramie High School, boys were prohibited from wearing mustaches, beards, long sideburns and hair touching the ears. In November 1970, 123 of the 900 Laramie High students petitioned the school board for a modification of the hair and dress code, but were denied.

Yearbooks for high schools in Cody and Cheyenne from the early 1970s show photos of many boys with hair covering their ears and eyebrows, as well as sideburns and mustaches. This may reflect the same social trend toward long hair mentioned at the 1970 Casper-Midwest School Board meeting.

Although the Supreme Court’s 1970 refusal to hear the Wisconsin case settled the question for Casper and Midwest schools, the hair-length debate has never stopped, sometimes leading to litigation. In January 2019, the mother of a first-grader who wore dreadlocks to his Texas school refused to require her son to cut his hair after school officials invoked their rules against long hair.

Loren Evans’s three years’ absence from school, though he studied materials above his grade level at home, was a major personal event. Yet some Star-Tribune readers felt that hair length was a trivial barrier to education. Furthermore, only a few of these readers commented that they were much more concerned about social problems such as violence or government corruption. But given so many contemporary episodes of opposition to the Vietnam War, civil rights struggles and student unrest, the Evans’s local battle against established norms occupies a significant place in the story of the times.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Bronc. (Yearbook, Cody High School, Cody, Wyo.), 1970, 1971.

- Burgess, Robert A. Letter to Dr. Nathaniel E. Fowler, April 28, 1969. Loren Evans Vertical File, Casper College Western History Center, Casper, Wyo. (Hereafter WHC).

- Casper Star-Tribune. Articles and letters to the editor, April 2, 1969, March 13, 14, 26, 1969, May 16, 28, 29, 1969, Oct. 24, 1969, April 30, 1970, May 25, 28, 1970, Aug. 24, 1970. Newspapers.com. Database available to patrons at the WHC and at the Natrona County Public Library, Casper, Wyo. (Hereafter NCPL).

- Doyle, James E., District Judge, U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin. “Opinion, Order and Judgment.” Breen v. Kahl, Feb. 20, 1969, accessed April 18, 2019 at https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/Fsupp/296/702/1982747/.

- Earthflax. (Yearbook, Kelly Walsh High School, Casper, Wyo.), 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1974, 1975.

- Loren Evans Vertical File. Casper Star-Tribune. Articles and letters to the editor, Oct. 17, 1967, Nov. 26, 1967, March 5, 9, 10, 16, 19, 20, 23, 25, 1969, April 30, 1969, May 3, 23, 24, 1969, June 1, 4, 6, 10, 1969, Oct. 21, 1969, April 23, 1970, June 2, 3, 1970, July 3, 1970. Also available at Newspapers.com, to patrons at the WHC and NCPL.

- Mustang. (Yearbook, Natrona County High School, Casper, Wyo.), 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973.

- Pow Wow. (Yearbook, Cheyenne Central High School, Cheyenne, Wyo.), 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972.

- Wahina. (Yearbook, Cheyenne East High School, Cheyenne, Wyo.), 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972.

- Walsh, S. K. Policy on Hair Grooming for Boys, Casper-Midwest Schools, April 15, 1969. Loren Evans Vertical File, WHC.

- White, Philip Jr. “The making of automatons.” The Branding Iron, May 9, 1969. Loren Evans Vertical File, WHC.

- ____________. “Mother and son fight school board ‘lock’-out.” The Branding Iron, May 9, 1969. Loren Evans Vertical File, WHC.

Secondary Sources

- Brunsma, David L. The School Uniform Movement and What It Tells Us about American Education: A Symbolic Crusade. Lanham, Md.: ScarecrowEducation, 2004.

- Donnelley, Erin. “Mom says elementary school is demanding that her first-grader cut his dreadlocks: ‘I won’t conform to racist policies’.” Yahoo Lifestyle, Jan. 9, 2019. Yahoo.com, accessed June 9, 2019 at https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/mom-says-elementary-school-demanding-first-grader-cut-dreadlocks-wont-conform-racist-policies-120109868.html.

- Graham, Gael. “Flaunting the Freak Flag: Karr v. Schmidt and the Great Hair Debate in American High Schools, 1965-1975.” The Journal of American History 91, no. 2 (Sept. 2004): 522-543, accessed June 7, 2019 via JSTOR at https://www.jstor.org/stable/3660710?mag=the-high-school-hair-wars-of-the-1960s&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- Wills, Matthew. "The High School Hair Wars of the 1960s." March 10, 2018. JSTOR Daily, accessed June 7, 2019 at https://daily.jstor.org/the-high-school-hair-wars-of-the-1960s/.

- White, Phil. Wyoming in mid-century: prejudice, protest and the "Black 14." Self-published, 2018, 82-86, 229-230.

Illustrations

- The 1969 photo of Black 14 protestors is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks. The rest of the photos are from the Casper Star-Tribune collections at the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.