- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Grave of Charlotte Dansie

The Grave of Charlotte Dansie

Like many of their faith, Charlotte and Robert Dansie converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints while still young adults in England. After 13 years of marriage they determined to make their way with other Mormons to their Zion in the Salt Lake Valley. Crossing an ocean and a continent, would prove too much, however, and Charlotte, pregnant with her eighth child, would fail to finish the journey.

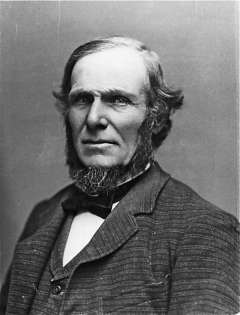

Charlotte Rudland and Robert Dansie were married April 8, 1849, in the parish church at Newton Green, Suffolk, England. They were residents of Boxford, Suffolk County, northwest of London. Robert was a blacksmith. Robert had been born Feb. 5, 1825, in Boxford and Charlotte Feb. 10, 1832, in nearby Newton. Their houses of birth still stand in their respective Suffolk villages. Robert described Charlotte to his grandchildren as a “beautiful wife,” small in stature with black hair and dark, flashing eyes.

Shortly after their marriage, the Dansies joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and then moved to Barking, Essex, a town near London. Disapproval of their new religion by their families and friends prompted the move. Robert became a gardener and took care of the grounds and flower gardens of a wealthy landowner. They left for America on May 12, 1862, with their five offspring, leaving behind in England the graves of two other children.

They sailed from Liverpool on May 14 aboard the sailing ship William Tapscott, which had been chartered by the church to bring 850 English saints to the United States. They arrived in New York on June 25 and docked the next day, arriving after 42 long days at sea, a voyage that harmed the health of many of the passengers.

The church had chartered a train to take the converts to Florence, Neb., the gathering point near Omaha on the Missouri River, where Mormons gathered to outfit for the trip to the Salt Lake Valley. The Dansies were assigned to the company of Capt. Ansil P. Harmon, who led one of six companies of teams sent east from Utah that year—so-called church trains—to bring Mormon emigrants to the valley. The Harmon company consisted of 48 wagons and nearly 500 individuals. They left Florence on Aug. 2.

John D.T. McAllister was elected president and chaplain of the company and unofficial journal keeper. He had made several similar trips between Salt Lake and Florence in previous years and now was returning from missionary work in Birmingham, England. From his journal we learn there were eight deaths while the company camped at Florence and probably at least 25 more, the majority children, many of them from measles, before the company in the third week of September reached a camp on the Sweetwater River a mile east of Twin Mounds as they approached South Pass.

Charlotte Dansie was expecting the birth of an eighth child, but we do not know how far along her the pregnancy was. She had suffered during the voyage, and her health had continued to deteriorate during the wagon journey. On the night of Sept. 20 the baby was born prematurely and lived just long enough for his parents to name him Joseph.

A Dansie descendant would remember years later that “before grandmother died she was in such pain that she told [her husband] she could stand her suffering no longer and asked him to pray to God that she might be released and return to her maker. Grandfather did pray and it was only a matter of minutes until both she and the baby died.”

The journal of John D.T. McAllister, president and chaplain of the company, notes, “September 21, Sunday. At 7 ½ o’clock a few of us went ahead to dig a grave for the body of Sister Charlotte Dansie, wife of Robert, age 32, who died early this morning of a “Miscarriage” and general debility. One mile brought us to the Summit or pass. Three more we made the Pacific Spring, one mile farther we crossed Pacific Creek and dug her grave on the right of the road[. W]hile [we were] digging the grave, Captain Harmon rode up and informed us that Caroline Myers, aged 25 was dead. She died of bilious fever just after the wagons left camp. We widened the grave for both bodies. We stopped there three hours then traveled 11 miles to Dry Sandy.”

Little is known about Caroline Myers (or Meyers) except for the sad circumstances of her death. She seems to have been traveling alone with no other family members, and does not appear on the list of passengers from the William Tapscott.

Caroline had probably been sick for several days, but on the morning of the 21st she began that day’s journey by walking ahead of her team. Diarist William Priest wrote, “When the wagons came, the teamster reported another death a young woman belonging to Bro Jarmin’s tent. She started to walk a little from camp but had to sit down on the road. The teamster of the wagon she belonged to would not take her up. The captain had her put in another wagon. She had only been in a few minutes and she died. The camp stopped to water the oxen where they was all buried.” [The passage has been edited for readability.]

Robert Dansie put a strand of blue beads around Charlotte’s neck and, from the family belongings, tore the lid off a large trunk, its brass hinges stamped with images of the British lion, and placed it over Charlotte’s body in the grave. The baby was buried in the arms of its mother who lay beside the body of Caroline Myers. After the burial a large rock was placed over the grave.

The Harmon company arrived in Salt Lake on Oct. 2. In December Robert married Jane Wilcox, who also had been a member of the company. They settled in Herriman, Utah, and had nine children together. In all, Robert and his two wives, Charlotte and Jane, had 13 children who lived to have families of their own, by which the Dansie family has continued to multiply and prosper in Utah and Idaho.

Some of Robert’s children later tried to locate Charlotte’s grave, but without success. In 1939 some members of the next generation, armed with an earlier letter to the family from D.T. McAllister, made another attempt. When they reached Pacific Springs they found a man they described as a “Mexican sheepherder” camped nearby. They asked him if he knew of any old graves in the area. He told them that some other sheepherders had dug into a grave he had noticed nearby, but when they found that three people were buried in the grave, two adults and a baby, it had been covered back up.

After they questioned him further, it began to appear to the Dansies that the man himself had dug up the grave. Becoming frightened, they said, he admitted to it and produced a string of blue beads that he had found in the grave. The necklace was recognized as the one placed by Robert around Charlotte’s neck before her burial.

At the grave, scrap metal from the trunk, copper rivets, brass hinges and lock engraved with the image of the lion, and old pieces of leather were scattered around the grave. All this evidence led the family members to believe that they had finally relocated the grave of Charlotte and Joseph Dansie and Caroline Myers.

Little more than a month later, the present monument and fence were installed and dedicated by more 80 members of the Dansie family. The senior Dansie present for the ceremony was Sarah Ann Dansie, Charlotte’s last surviving child, who had been 4 years old when she witnessed her mother’s burial 77 years before.

In 1958 President Eisenhower authorized the Secretary of the Interior to convey an acre and a quarter of land to be used as a grave site and memorial to Charlotte Rudland Dansie. The Dansie Family Organization now has a deed to this property, where every few years they hold family reunions.

The words quoted on the monument are from the Mormon rallying anthem, “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” written by William Clayton of the 1847 Mormon Pioneer Company that led the way into Salt Lake Valley. Clayton wrote the words while camped in Iowa 43 days out on the journey from Nauvoo to Winter Quarters—later Florence—in 1846. The fourth verse is as follows.

And should we die before our journey’s through,

Happy day! All is well!

We then are free from toil and sorrow too;

With the just we shall dwell.

But if our lives are spared again,

To see the Saints, their rest obtain

Oh, how we’ll make this chorus swell –

All is well! All is well!

Resources

Sources

- Brown, Randy. “The Grave of Charlotte Dansie.” Headed West: Historic Trails in Southwest Wyoming. Brown, ed. Mike W. and Gorny, Beverly. Sweetwater County Joint Travel and Tourism Board. Printed for the Oregon–California Trails Association 10th Annual Convention in Rock Springs, Wyoming. 1992.

- Dansie, Julian LeGrande. “Robert Dansie: Devoted Pioneer Father, Faithful Latter-Day Saint.” Privately printed. Dansie Family Association. 55 pages. No date.

- Dansie, Marvin. “Finding the Pioneer Grave of Charlotte Rudland Dansie after Seventy-five years.” Unpublished monograph, 6 pages. No date.

- Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel. Priest, William, "A record of my life, 1828," 42-62. https://history.lds.org/overlandtravel/sources/17501/priest-william-a-record-of-my-life-1828-42-62.

- Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. “Charlotte Dansie Grave.” Emigrant Trails throughout Wyoming, accessed May 2, 2017, at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/trailsdemo/charlottedansie.htm.

Illustrations

- The photo of the grave is by the author. The photo of Robert Dansie is from the author’s collection, courtesy of the Dansie family.