- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Ernest Hemingway In Wyoming

Ernest Hemingway in Wyoming

The Wyoming story of American novelist Ernest Hemingway began when he sought solace, seclusion and beauty near Yellowstone National Park. Its chapters span the entirety of his adult life yet have been accorded only passing significance. In Ernest Hemingway’s life, scenes of hunting, a wedding, miscarriage, injuries and physical degeneration all found Wyoming settings. Friendships grew, he fished with his sons, and he wrote much of his best work here—with great energy, productivity, and vividness.

Italy, World War I and Wyoming dreams

Ernest Hemingway, barely 19, had a lot of time to think during his six months’ hospitalization in Milan. He had been hit in the legs less than three weeks after coming to Italy as a United States Red Cross ambulance driver. In the room next to his was fellow ambulance driver Henry Villard, later to become a U.S. ambassador, who was suffering from jaundice. The two swapped tales about the size of trout they had caught back home and cooked with bacon over a fire. They reminisced about being far from civilization and spending days in a tent when it rained.

Villard described a ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River in Wyoming where he had spent the previous summer. “I am going to live out there, Hem,” he declared. Hemingway responded, “Hell, I’m going out there myself someday.”

Hemingway would mourn the loss of his mostly fantasized relationship with his nurse Agnes von Kurowsky.

He would marry and divorce Hadley Richardson and live in France and Spain; become a father; have an affair with Pauline Pfeiffer, a marriage to her, and a second son before he and his friend and fellow ambulance driver Bill Horne would load into Ernest’s yellow Ford runabout and head west.

“Wine of Wyoming”

Hemingway had already published the novel The Sun Also Rises and the short-story collections In Our Time and Men Without Women when he arrived at the Folly Ranch near Sheridan in July 1928, just a month after the birth of his second son, Patrick.

Hemingway had left the sweltering Midwestern heat for the cool, clear air of the Wyoming mountains. He and Horne arrived in Sheridan and found their way to the Folly Ranch in the Bighorn Range. The ranch log includes an entry in which a Dr. Spaulding was summoned in the middle of the night to treat Hemingway’s “twitching insomnia,” likely restless legs syndrome.

That summer, at age 29, he wrote to a friend from the ranch that he was “lonely as a bastard,” was drinking and eating too much, and that his whole life seemed pointless. He hoped to finish A Farewell to Arms , set in Italy during World War I, before Pauline arrived. Pauline’s recent difficulty giving birth to their son, Patrick,was the model for Catherine’s death during childbirth in A Farewell to Arms . Bothered by the noise and the tourists at the Folly Ranch, Hemingway moved to the Sheridan Inn, built in 1893 by the Burlington Railroad, then to the Donnelly Ranch and eventually to the Spear Family Ranch, called Spear-O-Wigwam. In August, Pauline joined him, having left infant Patrick to be cared for by her parents and sister.

After Pauline arrived, the two ate and drank wine in Sheridan with the Moncini family, immigrants from France. This was during Prohibition, making the Moncinis bootleggers with an arrest record. Hemingway renamed them the Fontans in his short story “Wine of Wyoming.” Despite the idyllic setting and the narrator’s happy associations with Europe, the story reveals glimpses of trauma and the restlessness of Hemingway’s psyche. Some scholars have centered on Prohibition and the political situation to which the story alludes. But Hemingway had been greatly affected by Gertrude Stein and her coterie of artists and writers in Paris after the war.

What came of their association was a movement called Dadaism. Dada means hobby horse in French, and the expatriates in Paris were attempting to deal with their war-wracked,demoralized state by simplifying their art and writing to the point of absurdity and child’s play. “Wine of Wyoming” seems in many ways to fit this Dadaist model.

The expatriates were influenced by dreams, the unconscious, and free association. They rejected the bourgeois in society and the Victorian age and used this model to protest the insanity of war. One of the strongest influences was cartoonist George Harriman’s cartoon strip Krazy Kat in the New York Times . In the case of Hemingway, heavy drinking seems to have contributed to the nonsensical style of “Wine of Wyoming.”

Wister and Yellowstone

Pauline and an exhausted Ernest headed for Yellowstone National Park after he finished A Farewell to Arms . On the way, they stopped in Shell, Wyo., on the west side of the Bighorns, to meet Owen Wister, who wrote The Virginian , the most famous western of its time, set in Wyoming. Wister was an ardent supporter of Hemingway’s work, and the two shared a dedication to observation and detail.

Wister was born in 1860. By the time he died in 1938, he said, “It’s not my world anymore.” Hemingway would remember Wister as a “sweet old guy” and “most unselfish and loving,” one of the few writers he ever liked. Wister was an old-fashioned gentleman and one of the last of a vanishing breed.

After taking in the beauty of Yellowstone National Park, Hemingway and Pauline concluded their automobile trip in Casper, where they caught the train to visit Pauline’s family in Piggot, Ark. Hemingway reportedly wrote 600 pages in Wyoming that summer, which was about the same number of fish he and Pauline had caught during their stay.

The L Bar T near Cody

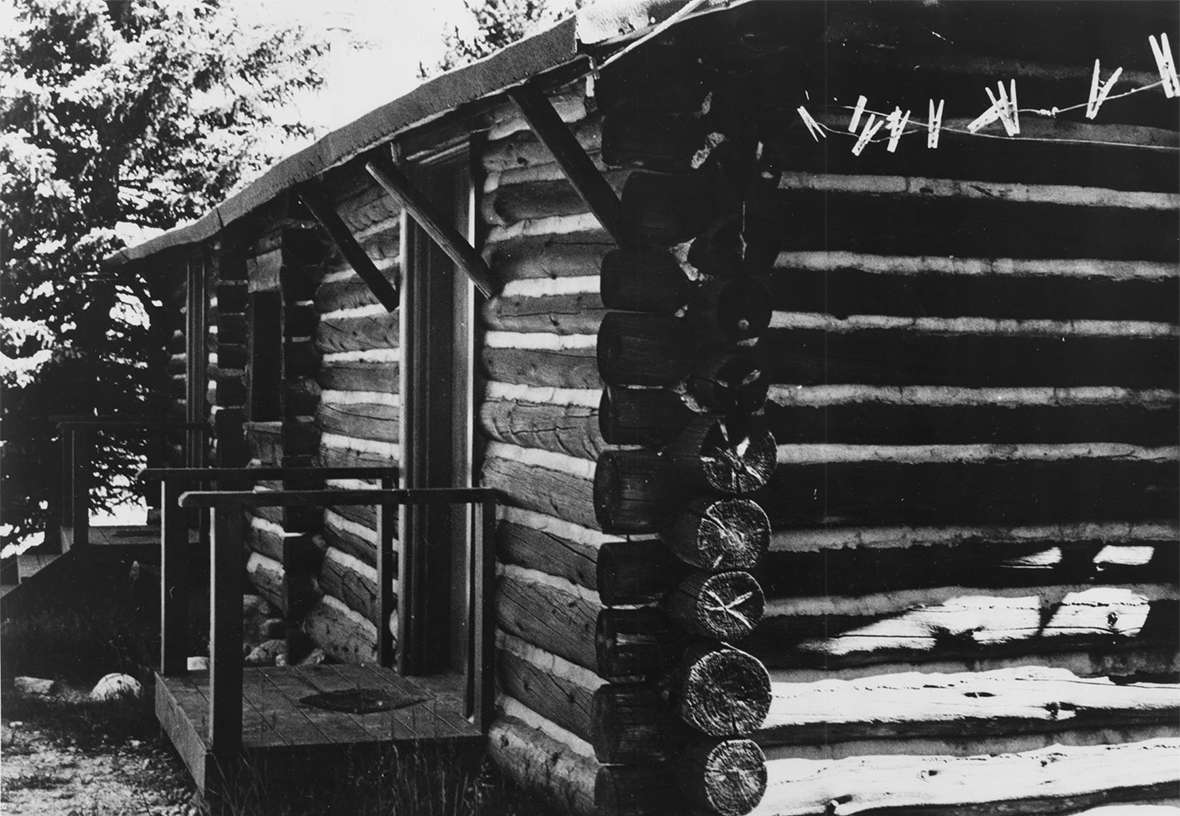

In 1930, Hemingway, Pauline, and Ernest’s son Jack (Bumby) returned to Wyoming, this time traveling to Cody, Wyo., named for its founder, Wild West showman William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. From there, the Hemingways found their way to the L Bar T Ranch, northwest of Cody, in Wyoming but near Cooke City, Mont. The ranch was owned by Olive and Lawrence Nordquist, who would become his friends. Ernest liked the L Bar T because no one seemed to know him there and when they learned who he was, they didn’t seem to care. Olive Nordquist reported that Hemingway started each day with a big breakfast and half a bottle of wine, then retired to his cabin to write. For the rest of the day, he drank whiskey. He was working on Death in the Afternoon , his bullfight book.

That first year at the L Bar T, there were reports of a black bear bothering cattle on the South Fork of the Shoshone River. Hemingway and the other hunters killed a horse, sliced it open and left it in the sun to rot. When the bear was attracted, they shot her.

Whether it was recklessness, alcohol, sheer accident or some combination, injuries plagued him. After killing a grizzly at the L Bar T, Ernest galloped triumphantly down the mountain, smashed his knee and had to be taken to the Cody hospital, where he suffered septicemia. In another accident, he slashed his face while hunting and required stitches. Accidents are a recognized manifestation of PTSD, especially in those who have experienced war.

In November 1930, he rolled his car while trying to avoid an oncoming car on one of the narrow roads of the time. A spiral fracture of his arm required several surgeries and a two-month recovery in the hospital in Billings, Mont. In true Hemingway fashion, he made notes and observations that would become the short story “The Gambler, the Nun, and the Radio.”

In 1936, Hemingway worked on To Have and Have Not at the L Bar T. The book is violent, with death or the threat of death as a constant theme. He wrote to poet Archibald MacLeish from the ranch that he had killed two grizzlies. He would later kill another.

In the letter, he told his friend, “Me I like life very much. So much that it will be a big disgust when have to shoot myself.” And he lamented that no one liked what he wrote anymore. He hadn’t had a big hit since A Farewell to Arms .

In 1939, Ernest brought with him to the L Bar T the portable radio he had carried during the Spanish Civil War. On Sept. 1, 1939, he ran out into the field, shouting for anyone to hear, “The Germans have marched into Poland! The Germans have marched into Poland!” It was a watershed moment and the end of an era; World War II had begun in Europe. Ernest would never again return to the L Bar T.

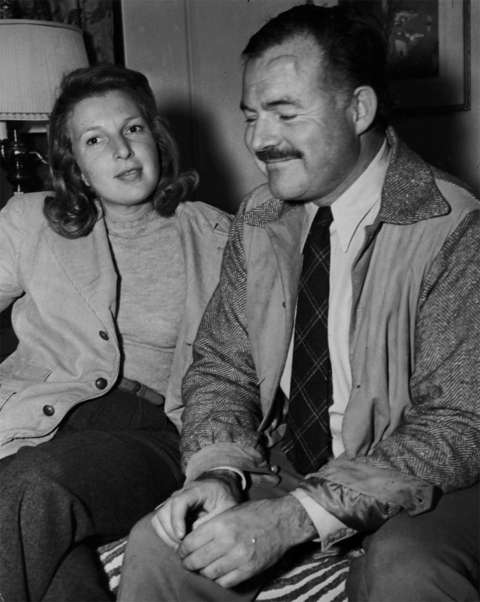

That last visit to the L Bar T was a watershed in another way. Within the span of a few days in July, Hemingway had separate encounters with two of his wives, Martha Gellhorn, whom he would soon marry, and all his children. The meeting with Hadley Mowrer (now remarried) focused on their son, Bumby. Later, Pauline flew out to meet him; his intent was to use this time to end their marriage. Without missing a beat, Hemingway left with Martha to drive to Sun Valley, Idaho, before Martha, a journalist, set out to Finland to cover the war.

He had met the restless and ambitious Martha in 1936 at Sloppy Joe’s café and bar in Key West, Fla. The history of Hemingway’s triangulations was repeating, with Martha now the third party, just as Pauline had been when Ernest and Hadley were married.

Cheyenne and a new wife

Ernest and Pauline divorced in November 1940, and again without missing a beat, Ernest and Martha were married that same month by a justice of the peace at the Union Pacific Railroad depot in Cheyenne.Traveling by train, they got off to get married, then traveled on to New York. Almost as if it were a honeymoon present, Martha begged Hemingway to go with her to China. There, she covered the war in China for Collier’s Magazine , and Ernest secured a magazine assignment of his own. He called her “Ambition” and she called him “U.C.” for “uncooperative companion.”

He could also be called spy: A Soviet-era document reveals that before he left for China, Hemingway signed on for espionage with the Soviet Union.

In 1944, as both covered the war, Martha arrived in England where Hemingway was recovering in the hospital from a concussion caused by an auto accident after a drunken party. She was not inclined to be sympathetic, as she despised his overeating and drinking. In London, Hemingway met and began to court Mary Welsh.

Mary worked as a feature writer for Time , Life and Fortune magazines. He was still married to Martha, but their marriage was unraveling. Martha divorced him in 1945, and he and Mary married in 1946 in Cuba. Richard and Marjorie Cooper hosted the wedding reception at their flat in Vedado, Cuba. Richard had served in the British army but also had ties to Wyoming. Their gift to the Hemingways was a set of silverware engraved with a custom design that included mountains, arrows and military insignia.

Casper and a difficult pregnancy

In 1946 in Casper, Hemingway again witnessed a wife endure a dangerous pregnancy. Mary was admitted to Natrona County Hospital with an ectopic pregnancy and a ruptured fallopian tube. After hours of intense pain, her veins collapsed, and the attending physician declared he could do no more.

Ernest scrubbed and flew into action, demanded the physician find a competent vein and give plasma. Ernest manipulated the bag and line until it flowed. After more plasma, blood transfusions, and surgery, she survived. For Ernest, this was proof that “fate could be f--ked.”

Hemingway met his sons in Rawlins and took them to Casper, where they fished in the North Platte River while Mary rested in the hospital. At the Mission Motor Court in Casper, Ernest began the manuscript that would later become Garden of Eden . At the same time, he was writing the novel, Across the River and into the Trees. The setting is once again Italy, yet Wyoming makes an early appearance.

In the novel, Jackson, the driver, is an auto mechanic from Rawlins. He talks about going to that “big place,” the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, to look at paintings because he thinks he ought to. The colonel reminds him the painters were restricted to religious subjects and asks him his theories on art. Jackson remarks he wishes they would paint some of the high country around Cortina, the “sunset color rocks, the pines, and the snow and all the pointed steeples.”

“If I had a joint or a roadhouse or some sort of inn, say, I could use one of those,’ the driver said. ‘But if I brought home a picture of some woman, my old woman would run me from Rawlins to Buffalo. I’d be lucky if I got to Buffalo.”

“You could give it to the local museum.”

“All they got in the local museum is arrow heads, war bonnets, scalping knives, different scalps, petrified fish, pipes of peace, photographs of Liver Eating Johnston, and the skin of some bad man that they hanged him and some doctor skinned him out. One of those women pictures would be out of place there.”

Later, on the causeway entering Venice, the colonel says to Jackson, “…It’s a tougher town than Cheyenne when you really know it, and everybody is very polite.”

“I wouldn’t say Cheyenne was a tough town, sir.”

“Well, it’s a tougher town than Casper.”

“Do you think that’s a tough town, sir?”

“It’s an oil town. It’s a nice town.”

“But I don’t think it’s tough, sir. Or ever was.”

“O.K., Jackson.”

Liver Eating Johnston was not the only mountain man to make his way onto a page of Hemingway’s. In 1948, a former Soviet spy gave testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which came uncomfortably close to the writer. In a letter to his friend Charles “Buck” Lanham, Hemingway offered a “Jim Bridger defense.” Yes, he had done odd jobs for the Soviets, he said, but he was trustworthy like Bridger. He compared his actions to those of the fur trapper, who had mediated between Indian tribes and encroaching settlers.

The Lanham friendship was sealed during World War II. Hemingway served as a war correspondent embedded with Colonel Lanham’s infantry regiment in France and was later reprimanded for military activities that were not allowed in his role as a correspondent.

Hemingway lived by his own code. In literature, it had to do with his revolutionary writing style.

A long Wyoming friendship

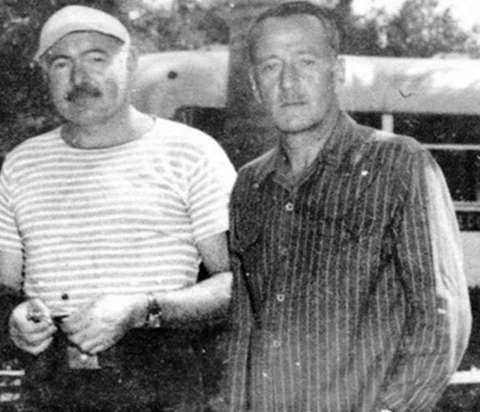

Hemingway visited Richard and Marjorie Cooper in Wyoming. More often, the Coopers and Hemingways met in Cuba, Bimini, and Tanganyika, where the Coopers owned a tea plantation.

Cooper’s entrepreneurial father, Frank, had moved his wife, son Richard, and daughter Barbara from Medicine Bow, Wyo., back to England but had to return to Wyoming in 1904 when oil was discovered in McFadden, near Medicine Bow (setting for The Virginian ). Richard Cooper had to maintain residence in Wyoming to collect the royalties.

Hemingway and Cooper shared more than a friendship. At different times they both had affairs with the same woman, Jane Mason, in Africa and Cuba. This worldly, wealthy lifestyle meant the Hemingway and Cooper children were frequently without their parents. The Coopers’ son and daughter were left in the care of Cooper’s sister Barbara in the Laramie home at Grand Avenue and 15th Street. (The house is now home to the University of Wyoming’s American Studies program.)

In 1951, Hemingway endured a string of losses. Richard Cooper drowned in three inches of water in a lake in Africa. Both Ernest’s mother and his former wife Pauline died in 1951, and he expressed considerable remorse.

Hemingway was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Old Man and the Sea in 1953. In 1954, he was awarded the Nobel Prize, but was unable to travel to Sweden because of declining health.

Casper again

The last Hemingway site in Wyoming is again Casper. His friend A.E. Hotchner described the April, 1961, scene. Ernest was on a flight from Idaho to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he received electric shock treatment for depression. The plane stopped in Casper for repairs, and he tried to walk into the moving propeller, presumably an attempted suicide.

At 61, Hemingway was battling depression, diabetes, high blood pressure, and liver disease caused from years of hard drinking.

When two professors from the University of Montana had come to Ketchum the previous November to invite Hemingway to lecture, they were stunned by his frail appearance and demeanor: He spoke in spurts and didn’t want to discuss his writing at all. The scene was reminiscent of Hemingway’s visit with Owen Wister more than 30 years earlier in that they considered Hemingway “enormously considerate,” gentle, and a man with “Old World manners.”

The electroshock therapy resulted in memory loss and an inability to string words together. After a second hospitalization, again at Mayo with more electroshock, he was discharged with the prognosis that he was improved, yet Mary felt that he was not. Though she had locked up the guns, Ernest knew where the keys were. On July 2 ,1961, in Ketchum, he held a gun to his forehead and, like his father, pulled the trigger.

In Hemingway’s story, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” first published in Esquire in 1936, a dying writer waits to be flown out of the African bush for treatment of gangrene. In his fevered state, he remembers Wyoming:

But what about the rest that he had never written?

What about the ranch and the silvered gray of the sage brush, the quick, clear water in the irrigation ditches, and the heavy green of the alfalfa. The trail went up into the hills and the cattle in the summer were shy as deer. The bawling and steady noise and slow moving mass raising a dust as you brought them down in the fall. And behind the mountains, the clear sharpness of the peak in the evening light and, riding down along the trail in the moonlight, bright across the valley. Now he remembered coming down through the timber in the dark holding the horse’s tail when you could not see and all the stories he meant to write.

Resources

- Bak, John S. Homo Americanus. Madison, Wisc., and Teaneck, N.Y.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2010.

- Baker Carlos. Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story . New York: Charles Scribners’ Sons, 1969.

- Baker, Carlos. Ernest Hemingway: Selected Letters 1917-1961 . Charles Scribners’ Sons: New York, 1981.

- Buckley, Peter. Ernest . New York: Dial Press, 1978.

- Egolf, Jamie. “The Cooper-Hemingway Connection.” Laramie Boomerang , 1980.

- Egolf, Jamie, and Kelley, Chavawn. “Ernest Hemingway, Wilderness of Wyoming and Wilderness of the Psyche.” Paper presented at Creativity and Madness, American Institute of Medical Education conference, Santa Fe, N.M., August, 2011.

- Goodheart, Eugene.Critical Insights: Ernest Hemingway . Pasadena, Calif.: Salem Press, 2010.

- Gutkind, Lee Allan. “Hemingway’s Wyoming,” “Bearskin Tempting,” and “Why Did Hemingway Leave Wyoming?” Billings Casper Star-Tribune , Oct. 19, 20 and 21, 1970.

- Hemingway, Ernest. A Farewell to Arms. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929.

- Hemingway, Ernest. Across the River and into the Trees. Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1950.

- Hemingway, Ernest. “The Clark’s Fork Valley, Wyoming.” In White, William, ed. Byline Ernest Hemingway: Selected Articles and Dispatches of Four Decades. Article republished from Vogue Magazine , 1939.

- Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon. Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, 1932.

- Hemingway, John, Patrick and Gregory. The Complete Stories of Ernest Hemingway . The Finca Vigía Edition. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1987.

- A.E. Hotchner, “Hemingway, Hounded by the Feds,” New York Times , July 1, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/02/opinion/02hotchner.html

- Moran, Eugene V. “Ernest Hemingway in the Sunlight Basin of Wyoming.” Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal , 77:1(Winter 2005): 293. Quoting Carlos Baker, Ernest Hemingway.

- Reynolds, Michael. Hemingway, The Final Years . W.W. Norton and Company. New York. 1999.

- Reynolds, Nicholas. Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy: Ernest Hemingway’s Secret Adventures, 1935-1961 . New York: HarperCollins, 2017.

- Sidley, Cornelia, Denver. Telephone interviews by Egolf, March21, April 14, and May 16, 2011, about the William Sidley diaries and Hemingway visits to the Silver Spur Ranch near Saratoga, Wyo., which the Sidleys owned.

- Slack, Judy, Wyoming Room, Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library, Sheridan, Wyo. Telephone interview by Egolf, May 16, 2011. Slack is the author of a book compiling numerous clippings, photos and diary entries about Hemingway’s 1928 stay in the Bighorns.

- Sojka, Greg. 1989. “Hemingway in Wyoming.” Paper presented at the Sense of Region: Cultural Patterns and Human Landscapes, Rocky Mountain American Studies Association Annual Meeting, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo. April 21-22, 1989.

- Villard, Henry Serrano, and James Nagel. Hemingway in Love and War: The Lost Diary of Agnes von Kurowsky, Her Letters, and Correspondence of Ernest Hemingway. Boston, Mass.: Northeastern University Press, 1989.

- Wagner-Martin, Linda, ed. Hemingway: Eight Decades of Criticism. East Lansing, Mich.: Michigan State University Press, 2009.

Illustrations

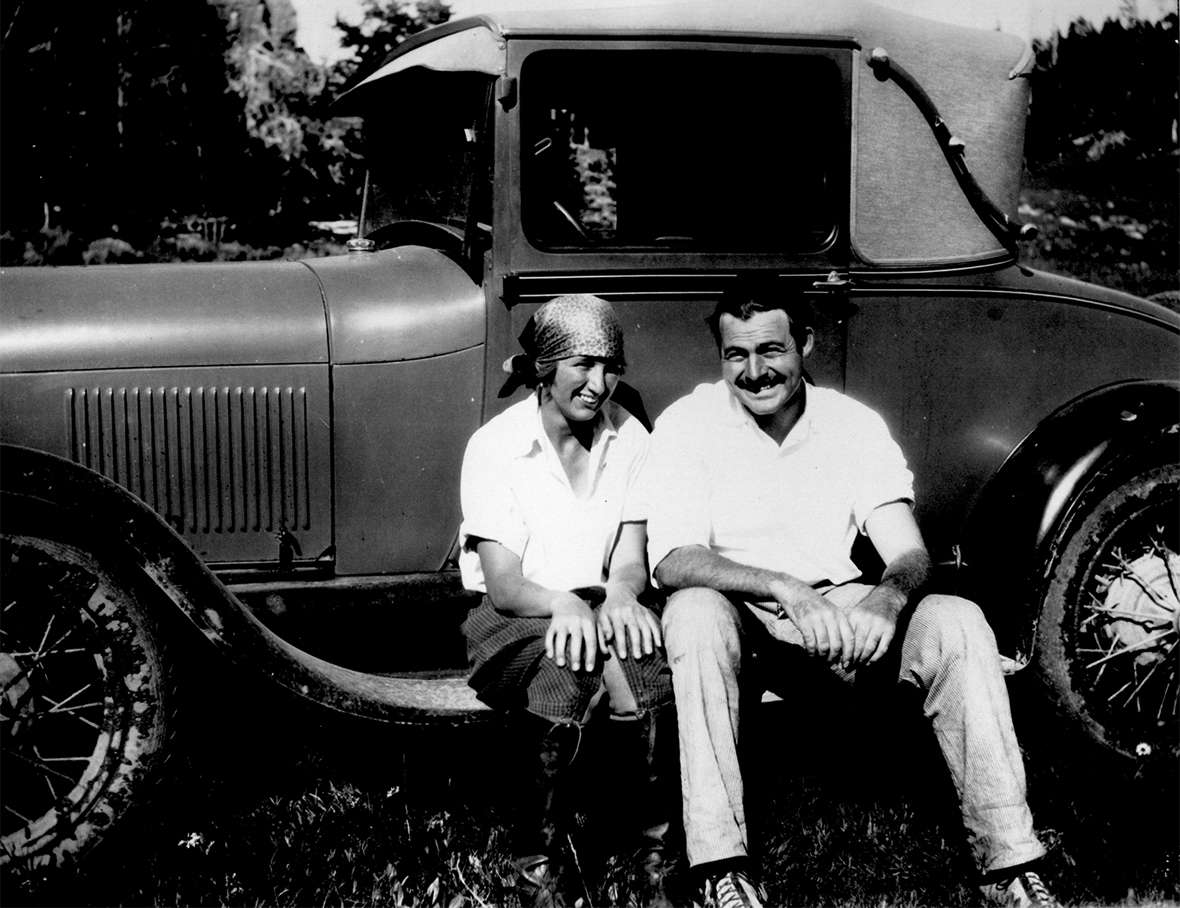

- The photo of Ernest and Pauline Hemingway in 1928 is from the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

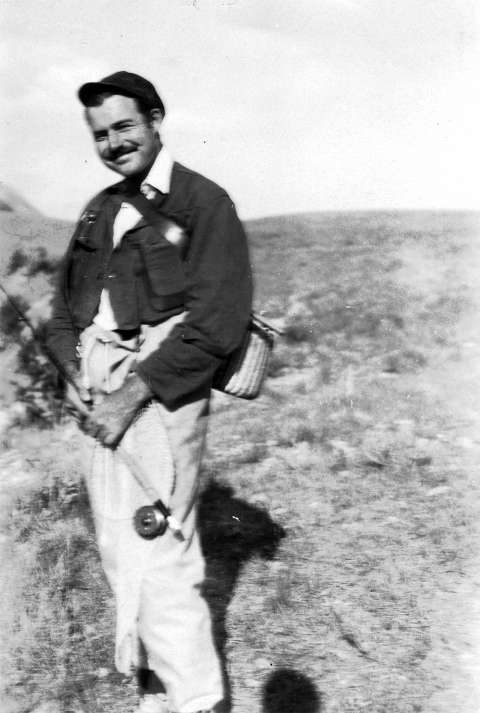

- The photo of Hemingway, his car and Bunny Thorne, 1928, is from the Wyoming Room at the Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Ernest and Pauline en route to Wyoming from Paris, 1934, is a file photo from a Casper Star-Tribune story published in 1970. The photo of the cabin that they stayed in at the L Bar T, taken by Lee Gutkind, is from the same news story. Both are from Casper Star-Tribune Collection, Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Pilot Peak from the L Bar T is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of Hemingway fishing in Wyoming, Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn in Sun Valley and Hemingway and Mary Welsh Hemingway in Venice are from the Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Library. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Hemingway and Richard Cooper was given to author Jamie Egolf by Hemingway biographer Carlos Baker in 1985. Used with permission and thanks.