- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Astorians Discover South Pass

The Astorians Discover South Pass

In August 1812, one of the natives whose people had used South Pass to cross the Rocky Mountains for centuries mentioned this natural corridor to an American fur trader. And the history of this great pass, as well as that of the United States, was set on a course of change.

The previous October, Wilson Price Hunt, a partner of fur-trade mogul John Jacob Astor in the sprawling Pacific Fur Company, had left St. Louis with four other partners, a clerk, 56 voyageurs, a woman, two children, and 82 horses. After wintering on the Nodaway River 400 river miles up the Missouri from St. Louis, the group continued up the Missouri to the Grand River, where they left the bigger stream to avoid the Blackfeet tribe, with whom Lewis and Clark had had so much trouble five years earlier. The Grand took them west across present South Dakota.

Hunt crosses the Rockies the hard way

From there, they set out overland across the Powder River Basin and the Bighorn Mountains of present Wyoming to the Wind River, across the Continental Divide at Union Pass, and down the Hoback River to its confluence with the Snake, where Hunt dispatched four trappers to collect furs. Leaving his horses behind, Hunt set out with 15 dugout canoes to descend the "Canoe River," now known as the Snake and considered one of the West’s most treacherous watercourses.

The voyage came to a disastrous end among the rapids of Caldron Linn below today’s Minidoka Reservoir in southern Idaho, when a canoe capsized and a voyageur died. It was clear the river was no longer navigable. These westbound "Astorians" divided into smaller parties and made their way down both banks of the Snake to the Columbia River and into the Oregon Country. In mid-February 1812 Hunt finally reached Fort Astoria, the company’s headquarters at the mouth of the Columbia, after traveling "2,073 miles since leaving the village of the Arikara [on the Missouri River]. July 18th to February 15th—7 months."

But, having arrived at Fort Astoria, Hunt discovered only bad news. Astor’s ship, the Tonquin, had earlier sailed around Cape Horn and established Fort Astoria. After the post was established, Tonquin Captain Jonathan Thorn, a notorious martinet, took a smaller crew and sailed north along the coast to trade for furs. Near Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island, Thorn insulted the local chief. The natives attacked and nearly all of the crew were killed. One survivor blew up the powder magazine, destroying the ship and himself. This left the Americans at Astoria with no transport home for themselves or their furs—and that and other information had to be communicated to Astor in New York.

Stuart heads east

Thus, on June 29, 1812, the guns at Fort Astoria saluted as Robert Stuart set off on a return journey with several companions. At least three of the party had come west with Hunt and knew the challenges that lay ahead. The travelers met two barges and ten canoes at Tongue Point and departed the next morning with a larger contingent of traders and trappers bound for the Spokane and Okanogan rivers and "the interior parts of the country above the forks of the Columbia."

Stuart made a difficult crossing of the Blue Mountains and the Grande Ronde Valley and an equally tough ascent of the left bank of Snake River before reaching the Bruneau River, in what is now southwest Idaho, in mid-August.

The next morning the Astorians met the Shoshone who had guided Wilson Hunt’s outfit "over the Mad River Mountain last Fall." Members of the Absaroka tribe—Crow Indians—had raided the Pacific Fur Company caches, the Shoshone reported, "and carried off every thing."

An easier way

But he also had more important news: "Hearing that there is a shorter trace to the South than that by which Mr. Hunt had traversed the R. Mountains," Stuart wrote the next day, "and learning that this Indian was perfectly acquainted with the route, I without loss of time offered him a Pistol a Blanket of Blue Cloth—an Axe—a Knife—an awl—a Fathom (of blue) Beads a looking glass and a little Powder & Ball if he would guide us to the other side, which he immediately accepted." Two days later, the erstwhile guide disappeared with Stuart’s horse.

This appears to have been the first hint of the existence of South Pass in the annals of the American West. French and American fur traders wandered the northern Rockies even before the return of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and Indian nations such as the Shoshone, Arapaho, and Absaroka had used the corridor for centuries, but no one of European extraction appears to have so much as heard a rumor of its existence before that fateful day in August 1812.

Since leaving the Columbia River, the Stuart party had essentially followed what later became the Oregon Trail, but concerned about meeting Crow warriors, Stuart decided against crossing directly from the Bear River to the Green. Instead, he turned north, leading his band, low on food now and hungry, up Thomas Fork on a wandering trek that covered 417 miles, by his own estimate, to reach the Big Sandy, less than one hundred miles from the start of their detour.

Horses stolen from hungry men

But their concern about the Crows had not been misplaced. On September 19, the Crow made off with all the horses of the Astorians. "Destitute of horses," the men later recalled, "the party hardly knew what to do." Some were ready to give up all hope "and die where they were, as it seemed hardly possible to cross the immense prairies on foot, weak as they had become and destitute of provisions."

A newspaper report the following spring explained, "Some idea of the situation of those men may be conceived, when we take into consideration, that they were now on foot, and had a journey of two thousand miles before them, fifteen hundred of which was entirely unknown." Seeking to avoid the Crow and even more fearful of the Blackfeet, Stuart and his men roamed "through a country, in Mr. Stuart’s own words, 'more fit for goats than men.'" Barely surviving on trout, duck, beaver, elk and grizzly bear meat, the men traveled up Thomas Fork and up and down the Salt, Greys, Teton and Hoback rivers, and even took a raft trip down the Snake. At one point, Ramsay Crooks fell desperately ill. Some of the men wanted to abandon him, but Stuart refused. Pressing on, the party finally "reached the drains of the Spanish River"—the Green River Valley—on October 12.

The starving men hoped to find bison in the valley, but the tracks of an old bull "was all we had for hope," Stuart wrote. They continued to follow the Green, coming upon various recent Indian encampments. Eventually, they met six friendly Shoshone who were willing to trade for some badly needed meat and one broken-down horse.

South Pass

Eventually, they made their way to the Big Sandy, which they followed for a couple of days. But, fearing the Crow, they abandoned a broad trace left by traveling bands of natives and headed northeast. The Astorians’s route brought them to a camp at or near the spot where the wagon and Pony Express trails later crossed the Dry Sandy.

As they struggled to keep warm, Stuart and his men could see the broad plain of South Pass looming before them. "The ridge of mountains which divides Wind river from the Columbia and Spanish waters ends here abruptly," Stuart wrote in the bitter cold.

The next day, Oct. 22, 1812, after a "hard tramp," the beleaguered Astorians "passed thro a handsome low gap" to reach the far side of the Rocky Mountains.

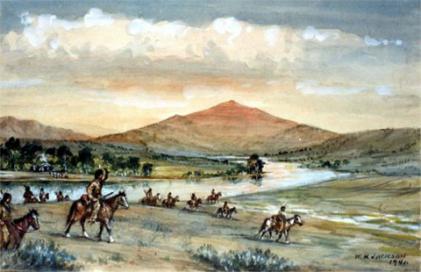

The party continued east, but south of the Sweetwater Valley and the route that later would become the Oregon Trail. Near Devil’s Gate they rejoined that route, and followed it to Red Buttes, west of present Casper, where they built a log hut—supposedly the first European cabin in Wyoming—and expected to spend the winter. After just two days, however, local Arapahoes were making them nervous and they moved on again, down the North Platte to a spot east of present Torrington, Wyo. In March 1813 they continued down the Platte and the Missouri, finally reaching St. Louis safely on April 30, 1813.

The seven white men who "discovered" South Pass were Robert Stuart, Ramsay Crooks, Benjamin Jones, François LeClerc, Robert McClellan, Joseph Miller and André Vallé.

Resources

- Stuart, Robert. The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart’s Narratives of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812–13. From the original manuscripts in the collection of William Robertson Coe, esq., to which is added: An account of the Tonquin’s voyage and of events at Fort Astoria and Wilson Price Hunt’s diary of his overland trip westward to Astoria in 1811–12. Translated from Nouvelles annales des voyages, Paris, 1821. Ed. by Philip Ashton Rollins. New York, N.Y: Eberstadt & Sons, 1935. Paperback edition, Lincoln, Nebr: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- Stuart, Robert. On the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart’s Journey of Discovery. Edited by Kenneth A. Spaulding. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953.

For Further Reading

- Eddins, O. Ned. “Astorians from the Oregon Country to St. Louis,” accessed 5/1/12 at http://www.thefurtrapper.com/robert_stuart.htm.

- HistoryLink.org. “John Jacob Astor and Pacific Fur Company partners sign agreement in New York City on June 23, 1810,” accessed 5/1/12 at http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=9437.

Illustrations

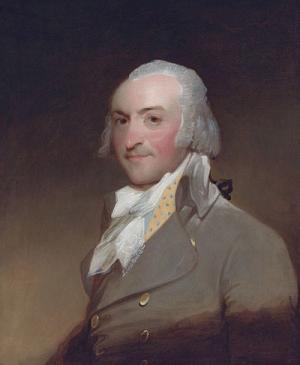

- The 1794 Gilbert Stuart portrait of John Jacob Astor is from Wikipedia.

- The photo looking north from Pacific Butte across South Pass at the Wind River Range is by Barbara Dobos. Used with thanks.

- Pioneer photographer William Henry Jackson painted many watercolors late in his life of scenes on the historic trails. This scene, painted in 1941, shows fur trappers crossing the North Platte west of present Casper, Wyo. near Red Buttes. From the Jackson Collection at Scotts Bluff National Monument. Used with thanks.