- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Wyoming State Hospital

The Wyoming State Hospital

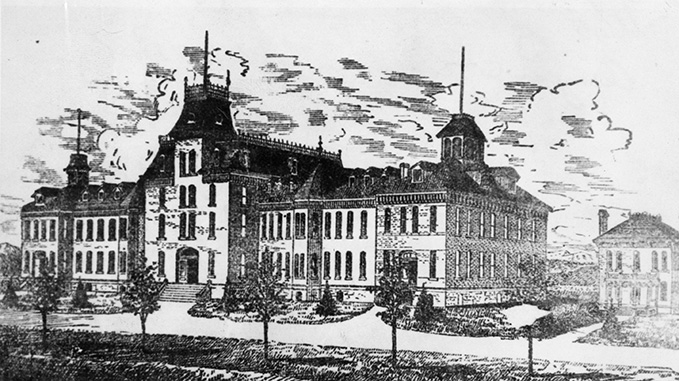

Originally established as the Wyoming Insane Asylum by the Wyoming Territorial Legislature in 1886, the Wyoming State Hospital in Evanston, Wyo. is dedicated to the care of mentally ill residents of the state. The story of the hospital is the story of an institution that evolved and a campus that was built according to trends in psychiatric thought and therapeutic practices.

The oldest part of its campus, a cluster of handsome brick buildings around a lawn shaded with cottonwoods, stands on a hill about a mile south of downtown and is visible from most of Evanston's downtown neighborhoods, as well as Interstate 80.

The hospital's stately architecture and peaceful setting are neither incidental nor accidental. Both were deliberately created to serve therapeutic purposes for the thousands of patients housed at the institution since 1889, when it opened. The hospital is also very much a part of community life, with a staff drawn from four generations of Evanstonians.

The Kirkbride model

When the Wyoming Insane Asylum was established, the idea of government responsibility for the care and treatment of the mentally ill was less than 30 years old. The chief agent of change was Quaker physician Thomas Kirkbride of Pennsylvania, who advocated what he termed “moral treatment” of the insane, and argued that asylums ought to have a curative rather than simply a custodial function.

Kirkbride's principles were published in 1854 in his book On the Construction, Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane. The chief features of his model were a country setting for the institution on at least 100 acres; a fireproof building constructed of stone or brick with a slate or metal roof that would house both patients and staff; a maximum population of 250 patients; and pleasant surroundings, intellectual amusements and “rational discussion” to encourage patients to regain their mental balance. Kirkbride placed special emphasis on training staff to treat patients with gentleness and compassion.

By the 1860s, several states had created state asylums based loosely on the Kirkbride template. The establishment of the Wyoming Insane Asylum was thus part of a larger social movement.

In 1887, the Wyoming Territorial Legislature located the Insane Asylum in Evanston, appropriated $30,000 for its construction and stipulated that at least 100 acres be procured for the grounds so that land could be farmed to produce income to offset hospital expenses. A site was chosen on the southern edge of Evanston on a hill overlooking the town. Intentionally or not, the site fit the ideals of the Kirkbride model.

Local government, at first

Dr. William A. Hocker of Evanston was named superintendent and construction on the hospital began in June 1888. Hocker had served in the Territorial Legislature from 1879 to 1884 and was a logical choice for the post since he had been a strong advocate for a state mental institution.

The first building was a brick, two-story structure housing male patients on the first floor and females on the second. It also included space for administrative offices and living quarters for staff. At his own expense, Hocker built a superintendent's residence on the hospital grounds for himself and his family. On May 15, 1889, the hospital welcomed its first patients, transported by rail in a Pullman car from Jacksonville, Ill., where Wyoming Territory’s mentally ill had been previously housed.

The first governing body of the asylum was a local board of commissioners appointed by the legislature. The board included three prominent businessmen: A. C. Beckwith, William Crawford and Charles Stone. When Wyoming's state government was organized in 1890, the asylum was placed under the jurisdiction of the new state Board of Charities and Reform, abolishing local control of the institution.

In 1891 the board replaced Hocker with Dr. C. H. Solier. The change was apparently motivated by politics. Solier had graduated from medical school in 1888 and moved to Rawlins, Wyoming, in 1889 where he was the county physician and a surgeon for the Union Pacific Railroad. Those who wrote letters of support for Solier's appointment stressed that he was a “good Republican” (Hocker was a Democrat) as were all the members of the Board of Charities and Reform.

Green lawns and a new name

In many respects, the institution that became the Wyoming State Hospital was Solier's creation. His annual reports vividly demonstrate its evolution and show his commitment to the Kirkbride model for care.

In his 1894 report, for example, Solier asked the Legislature for funds “for grading, terracing, seeding to grass and setting out of trees around the asylum buildings. The great desirability, in fact the almost absolute necessity of a well arranged park and lawn around such an institution as this must be obvious to every one,” he argued. “It is not merely to appeal to the aesthetic tastes of the more refined and cultured, but it is in many cases really curative of mental disorder.”

In his report for 1895, Solier recommended a name change. “Most of the older states have already discarded this term [Asylum] and have substituted in its stead the word ‘Hospital,’” he explained. Accordingly, in 1897, the Legislature adopted the Wyoming State Hospital for the Insane as the name of the institution.

In 1896, Solier asked the Legislature for funds for a new building to house the growing population of male patients. By that time, the patient population had risen to 129--90 men and 39 women--from a total of just 31 in 1891. The steep increase was due to the low discharge rate—between 30 and 35 percent—of the population, dominated as it was by aging alcoholics and those suffering from general paresis resulting from syphilis.

Early farm and garment work

At the turn of the 20th century, doctors frequently believed it best to treat mentally ill patients by keeping them occupied with meaningful work. Farm work filled this purpose at the Wyoming State Hospital and, at the same time, served the economic needs of the institution. While male patients performed much of the work on the hospital farm, female patients were kept busy making and repairing garments and other items needed by hospital patients and staff. They also produced a variety of “fancy work” for sale to hospital visitors.

From the beginning, annual and biennial superintendents' reports chronicle the growth of the hospital farm, accounting for each bushel of vegetables and gallon of milk produced. Staff and patients alike worked on the farm. The number of buildings needed to support their work grew steadily. An icehouse was built in 1892; by the 1930s, structures included a kitchen and bakery, a dairy barn, livestock barns, a granary, a slaughterhouse, a root cellar and various sheds.

Already by the late 1910s, with a patient population above 300, the hospital farm was producing thousands of pounds of beef, pork, mutton and chicken per year, along with substantial crops of hay, wheat, oats and a wide range of vegetables. The hospital bakery supplied the bread consumed by staff and patients; by the 1930s, the farm was producing a large array of canned fruits and vegetables. In addition to feeding hospital patients and staff, much of the food produced was sold locally, fulfilling the original legislative mandate that the hospital be largely self-sustaining.

More patients, more therapies, more buildings

From 1906 through 1918, the hospital continued to change thanks to growing numbers of patients and new therapeutic considerations. Among these were new treatments, the separate spaces for different kinds of patients, and amenities as porches and walking paths that supported therapeutic goals.

In 1906, the legislature approved adding a new wing for male patients to the original hospital building. In 1907, lawmakers authorized construction of a building for women patients.

Designed by Cheyenne architect William Dubois, the women’s building was completed in 1910 and named Brooks Cottage in honor of Gov. Bryant B. Brooks. It featured open porches and spacious, well-lighted and well-ventilated interiors. Another new addition to the original men’s building included rooms for hydrotherapy, a new treatment believed to have a calming effect on patients.

Beginning in 1914, Solier was able to fulfill his plan for a park by creating a lawn planted with several hundred trees for shade and windbreaks, along with a concrete roadway from the main gate to the buildings, for use by “daily walking parties of patients.”

Fire destroyed the original building in 1917. Fortunately there were no injuries and the 1916 addition for male patients was not damaged. By 1918, a one-story fireproof cottage, also designed by Dubois, was under construction to house 45 of the “more disturbed and unmanageable male patients.”

“All of our male patients are now housed in modern, well-built and comfortably furnished fire-proof buildings,” Solier reported in 1918. “Each [ward] has a comfortable and spacious outdoor porch always open to patients and so sheltered that only in the severest winter weather will they be uncomfortable.”

In contrast to the picture Solier painted for the Board of charities and Reform, charges of abuse and maltreatment periodically arose. The most public, even notorious, of these were made by journalist E. T. Payton, who had been a patient at the asylum on several occasions beginning in 1899. For the next 20 years, Payton waged a campaign against Solier, claiming that patients were regularly beaten and forced to live in squalid conditions.

The Board of Charities and Reform undertook an investigation of the charges in 1903 but took no action. Payton believed that Solier was exonerated because of his political affiliation. In succeeding years, former patients also told their stories of abuse to various Wyoming newspapers, but the board steadfastly refused to take action against Solier. In 1923, a woman patient brought her charges of cruelty directly to the board but received no recourse.

In 1923, the name of the institution was changed a final time, to the Wyoming State Hospital. By then, the campus had matured into two distinct areas--the residential/administrative complex at the north end and the farm operations on the south. Construction continued through the 1920s. The patient census reached 460 by 1930.

In addition to buildings to house patients, tunnels were built linking the buildings' basements. The tunnels allowed for easier transport of meals and supplies in winter and secure transport of patients year round.

After nearly 40 years as superintendent—some would argue an autocratic one protected by his politics—Solier died in California in December 1930. In 1931, the Board appointed Dr. David Williams to replace him.

Judging from his first report in 1932, Williams seems to have taken up the work of the hospital where Solier left off. “Where it has been possible,” the Williams report states, “patients were assigned congenial, as well as useful occupations, and most of them having a preference for outdoor life, were engaged in farm work and the other departments outside.” Williams' account of a smooth transition did not mention the mass resignations of many of the staff loyal to Solier, nor the impending investigation of continuing charges of abuse against hospital staff.

New times, new treatments

By the mid-1930s life and work at the state hospital was coming under economic and social pressures. During the Great Depression, the only building added to the campus was the Building for the Criminal Insane in 1935, constructed as a Federal Works Project.

More important, radically different treatments began to emerge, intended to reduce the role of mental hospitals as custodial institutions for long-term care. These treatments included insulin-induced coma, electroshock, lobotomy and, after World War II, psychotropic drug therapy. Unfortunately, none of the superintendents' reports from 1933 to 1950 are extant, so it is difficult to gauge how these national trends played out at the hospital during this time frame.

In the 1950s and 1960s, two more trends affected the operation of Wyoming State Hospital. First was the rapid development of psychotropic drugs, used to control symptoms and regulate the behavior of the mentally ill, reducing the need for long-term care. The second was the emergence of a national policy calling for community-based mental health care, which relied on outpatient and day care facilities rather than more expensive hospitals for care of the nation's mentally ill. Both practices have resulted in a steady decline in patient populations in mental hospitals and the closure of many institutions across the United States.

By the 1960s, patient populations at the Wyoming State Hospital were fluctuating between 400 and 600 patients. Following national trends, hospital populations declined as the use of psychotropic drugs and community care became more common.

The facility now houses fewer than 100 residential patients at any given time, and several of the older buildings on campus have been abandoned. The staff concentrates on providing outpatient services. But the campus still stands on the hill as a symbol of the historical continuity of the hospital's statewide mission and of its role in Evanston's own history.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Manley, Woods Hocker. The Doctor's Wyoming Children: A Family Memoir. New York: Exposition Press, 1953. Woods Hocker was Dr. William Hocker’s daughter.

- Solier, C. H. Report of the Superintendent, Annual and Biennial Reports of the

- Wyoming Board of Charities and Reform for 1892-1930. Wyoming State Archives.

- Williams, D. B. Report of the Superintendent of the Wyoming State Hospital for 1932.

- Biennial Report of the Wyoming Board of Charities and Reform for 1930-32. Wyoming State Archives.

- “The State Insane Hospital.” Industrial and Homeseeker's Edition, Wyoming Times. Evanston, Wyo.: June 8, 1911, 5.

Secondary Sources

- Barbero, Kerry, Barbara Bogart and Dubbe-Molder Architects, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for the Wyoming State Insane Asylum, 2003. Wyoming State Preservation Office.

- Bogart, Barbara. “The Hospital on the Hill.” Annals of Wyoming 79, no.1 (2007): 2-10.

- Browne, W.A.F. What Asylums Were, Are, and Ought to Be. New York: Arno Press, 1976.

- Ewig, Rick. “E. T. Payton: Savior or Madman?.” Annals of Wyoming 79, no.1 (2007): 18-36.

- Prochaska, William. “Farming Operations at the State Hospital, Evanston, Wyoming.” Annals of Wyoming 79, no. 1 (2007): 11-17.

- Grob, Gerald N. The Mad among Us: A History of the Care of America's Mentally Ill. New York: Free Press, 1994, 47-48.

- Stone, Elizabeth Arnold. Uinta County: Its Place in History. Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H.

- Clark, 1924.

- Tomes, Nancy J. “A Generous Confidence: Thomas Story Kirkbride's Philosophy of Asylum

- Construction and Management.” In Madhouses, Mad-Doctors, and Madmen: The Social History of Psychiatry in the Victorian Era. Philadelphia: University of

- Pennsylvania Press, 1981, 121-143.

- Whitaker, Robert. Mad in America: Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring

- Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill. Cambridge, Mass.: Perseus Publishing, 2002.

Illustrations

- The 1930s picture of staff and patients on the hospital lawn is from the photo collections of the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The rest of the images are all from the collections of the Uinta County Museum. Used with permission and thanks.