- Home

- Encyclopedia

- From Wind River To Carlisle: Indian Boarding Sc...

From Wind River to Carlisle: Indian Boarding Schools in Wyoming and the Nation

Sharp Nose was a sub-chief of the Northern Arapaho tribe during the tumultuous period after the Indian Wars in the late 19th century, when the subdued tribes were pushed onto reservations. In the 1870s, The Northern Arapaho were supposed to transform instantly from hunters to farmers, in the long-wintered mountains and foothills of what’s now the Wind River Indian Reservation, surrounded by the newly carved Wyoming Territory. They were supposed to share resources with a tribe from a different cultural root whom they had recently fought against, the Eastern Shoshone. And the supplies promised by the federal government in fulfillment of treaties – both the tools to farm and the food to feed children – were sparse or non-existent.

Though Sharp Nose had been a respected warrior, he was not vainglorious in defeat, and attempted, like many tribal leaders, to ensure the survival of his people. To this end, he allowed his son, Little Chief, to be taken by train to a boarding school in faraway Pennsylvania, to learn “how to do as white men do” because, as he put it to an Indian agent, “there are not enough good men to show us how to plant and cultivate our crops.” In a dictated letter to Richard Henry Pratt, the U.S. Army veteran of the Indian Wars who founded the school, Sharp Nose wrote: “We give our children to the Government to do as they think best in teaching them the right way, hoping that the officers will, after a while, permit us to go and see them.”

But Sharp Nose would never see Little Chief again. The boy died in the infirmary at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1883, and was buried on the school grounds. Sharp Nose was in Yellowstone – guiding another chief, President Chester Arthur, on a fishing trip in the primitive park. In his tent, Sharp Nose cut off his long braids, a traditional sign of mourning. President Arthur would return east; but Sharp Nose had no means to travel and retrieve his son’s body.

The children who died at Carlisle were buried in graves located near what is now called the Jim Thorpe Fitness Center – named after a graduate of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School who became a fabled football and Olympic athlete. The school was built on a military outpost that dated back to the American Revolution, and the boys at Carlisle, some of whom had accompanied their fathers during battles against the U.S. Army, were dressed in Army-style uniforms. On their way to play sports at Carlisle they would have had a view of a cemetery of their peers.

Today, the Carlisle Barracks, as it’s called, is the U.S. Army’s War College campus, and on guided tours there is little mention of the boarding school era … except Thorpe, its most famous graduate. In 1927, the cemetery was moved to a less central location – a move that may have resulted in some careless scrambling of bones and grave-markers, as the Northern Arapaho would discover in 2017.

Assimilation, or cultural genocide?

There’s little mention of Indian boarding schools in American history books, though there were hundreds of them a century ago. Many were located on reservations, and many were run by religious orders, subsidized by federal funds. Others were intentionally built far from tribal homelands, following the model of Carlisle, to separate kids from the isolation of reservations and from what schools’ founders saw as the corrupting influences of traditional culture.

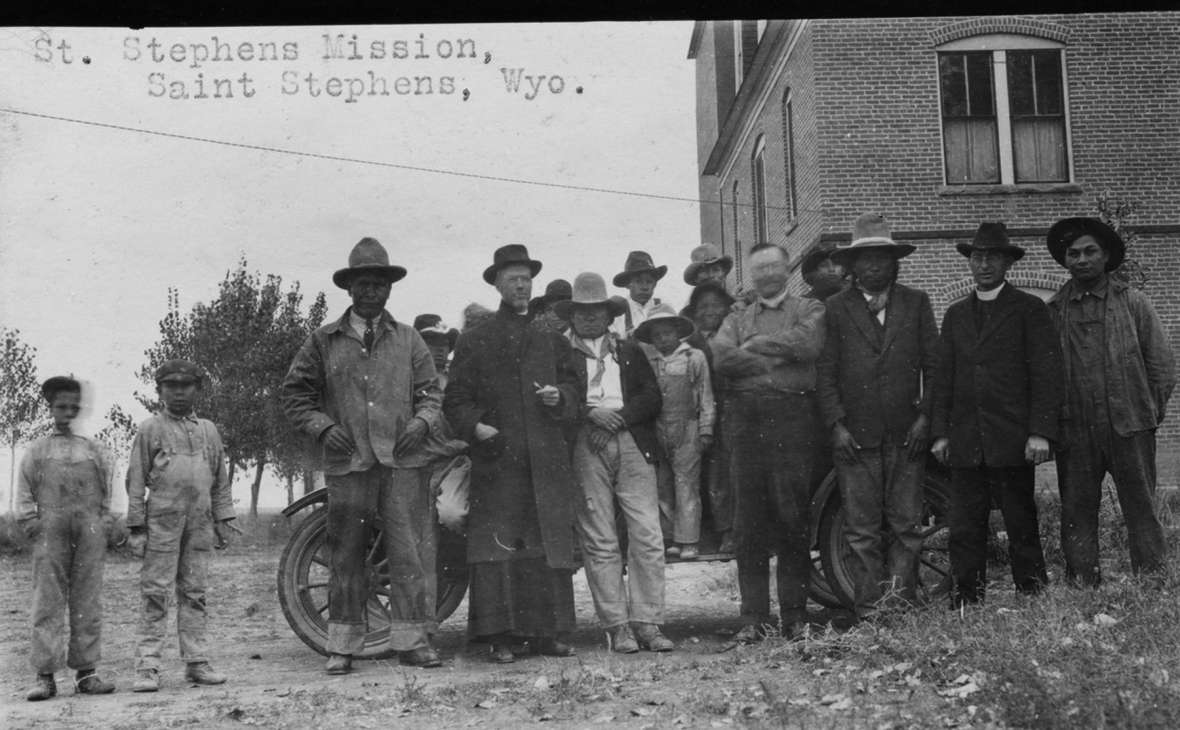

At the time Sharp Nose sent his son to Carlisle there were no boarding or day schools on the reservation, but that would soon change. In 1883, Episcopal minister John Roberts arrived at Wind River, and with the government Indian agent’s approval began teaching children in his one room cabin on Trout Creek, where “boarding” children slept on the rug. Jesuits arrived a few years later, and when they found Roberts entrenched on the west side of the reservation, they built their mission and school, St. Stephen’s, on the east side. In 1892, a government school went up near Fort Washakie, nicknamed “Gravy High” because of a staple food served in the dining hall. The government school was more severe in its methods – students were beaten for speaking their native languages, and military drills were part of the curriculum – but the religious schools also sought to reshape the tribes’ children in the ways of white society.

Education as a tool to “assimilate” indigenous peoples into the society that conquered them is as old as colonization, and, compared to slavery and other methods of subjugation, suggests a more benign intent. There were “practical” reasons as well. After the Civil War ended at Appomattox, the exhausted Army found itself pulled west into a prolonged war of attrition against scattered Indian tribes. It was expensive: Civil War general and Senator from Missouri Carl Schurz calculated that the geographically distended war against Indians cost the country $1 million per Indian killed, whereas it cost $1,200 to school an Indian for eight years, and presumably “civilize” him.

Many of those who decried the erasure of Native Americans – whose numbers in North America plummeted from more than 5 million when Columbus arrived to fewer than 250,000 in the 19th century – saw education as a way to “save” Indians by re-making them in the image of their conquerors. As early as the 16th century, Jesuit missionaries began schooling Indian children in Florida, and later, in the 19th century, the federal government would divvy up reservations among denominations and help fund their parochial schools with something called the “Civilization Fund.” That brought the Episcopalian Roberts Mission to Wind River, and the Catholic St. Stephens. But even with the salve of salvation, the aim was the same: By various methods, and in various locations, schools would be a weapon to, in the worlds of Carlisle founder Richard Henry Pratt, “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Carlisle, the boarding school where Little Chief and other Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone children were sent – along with children from as many as 140 other tribes – set the standard for Indian boarding schools. Life was highly regimented. Children who arrived in their finest traditional clothing, often bearing pipes and other gifts, were stripped of their tribal possessions and their hair was cut short. Their days were divided between academic classes – intensive English classes when they arrived, and then math, physiology, geography, and U.S. history – and a half day working at trade skills, such as carpentry and agriculture. The children also lived and worked for periods with white families in surrounding communities on “outings,” ostensibly for them to experience a non-Indian family and workplace, but sometimes merely providing their hosts inexpensive farm and domestic labor.

Pratt was a complicated figure. His experience on the frontier, working with black Army units and Indian scouts, had convinced him of the intelligence and ability of people of color. At the same time, he was critical of tribal life and the reservations, and argued that only by separating children from their families and tribe could they be molded into successful American citizens, weaned of communal tribalism and converted to individualism, work ethic, and patriotism. If Carlisle graduation rates are any indication, the experiment failed: By 1909, 4,151 students had been to Carlisle, but only 532 had graduated. Pratt, whose confidence in his own ideas never wavered, would say that a diploma wasn’t as important as the skills they now had to navigate the modern world.

The experiment fails

But many students – Little Chief, Horse and Little Plume from the Northern Arapaho among them – would never make it out of Carlisle. They would die there, of diseases like tuberculosis, measles and influenza. In 1881, the Superintendent of Indian Education reported that of 49 students brought to Carlisle in its first year, 10 had died. That figure may have understated the problem: chronically ill students were often sent home, so their deaths do not show up in Carlisle’s records.

“The children were much more vulnerable to all the European diseases, just as Native people had been down the centuries,” said Dr. Jackie Fears-Segal, a professor at the University of East Anglia. “They were also in a completely different climate. And they were surrounded by a different environment. And we know now, that anybody who is suffering emotional deprivation, their immune system is compromised.”

Students were dying at the boarding schools on reservations, too, and Rev. John Roberts, noting the heavy death rate of pupils at the Wind River government school, asked the government to let the children have more time with their families. He noted that despite good food and exercise, “in school, they droop and die, while their brothers and sisters, in camp, live and thrive.”

Roberts corresponded with Pratt, trying to convince him that Indian children would do better if schooled closer to home. Pratt, always blind to faults in his own vision, blamed the unhealthy condition of the children sent from Wind River. But it was becoming clear that the boarding school experiment – in this early form – was not succeeding.

Estelle Reel, who had been Wyoming’s Superintendent of Public Instruction, became the national Superintendent of Indian Education in 1898, in charge of government Indian schools nationwide. Reel was a hard worker, who traveled extensively among reservations and met with tribal leaders all over the country. But she took office with little respect for Indian children’s academic prospects, and she issued a massive “Course of Study for the Indian Schools” in 1901 that steered instruction at the boarding schools toward “practical” learning, like agriculture and manual tasks.

“Her expectations for them learning were very, very low,” said Michelle Hoffman, a Wyoming education consultant and former superintendent at Wyoming Indian Schools. “They were wonderful artisans, they could weave baskets and do artwork…but not the book type of education.”

That view of Indians, and the Pratt approach to civilizing them, would hold for another 30 years in federal programs for Indian education. Pratt would lose his job, and Carlisle would close in 1913, but other boarding schools – Haskell in Kansas, the Phoenix Indian School, Chemawa in Oregon, among them – would continue. Then, in 1928, the Rockefeller Foundation funded a study that became known as the Meriam Report, which exposed the dire conditions on reservations and the inadequacy of federal Indian programs, including the boarding schools.

"In nearly every boarding school one will find children of 10, 11, and 12 spending four hours a day in more or less heavy industrial work—dairy, kitchen work, laundry, shop,” the report’s authors wrote. “The work is bad for children of this age, especially children not physically well-nourished; most of it is in no sense educational ... At present the half-day plan is felt to be necessary, not because it can be defended on health or educational grounds, for it cannot, but because the small amount of money allowed for food and clothes makes it necessary to use child labor.”

After the Meriam Report, the federal approach to providing education for Indians—a responsibility written into treaties with the tribes—changed for the better. The military models were discarded, day schools were supported, primers in English and native languages were written, and tribal cultural activities were included or encouraged on campuses.

But Indian education, like Indian programs generally, was chronically underfunded; facilities were often in poor shape (though maintained with student labor), and the caliber of teaching was often sub-par. In 1969, a Senate special subcommittee on Indian Education summed up its 4,500 pages of testimony and research in its simple title: “Indian Education: A National Tragedy – a National Challenge.”

Boarding schools on and off the reservation began closing their doors, not just because of their poor reputation, but because improved roads and community growth gave reservation residents better access to local public schools. The boarding schools on the Wind River Indian Reservation were among the longest surviving: St. Stephens stopped boarding kids in 1939; Roberts’ school for girls closed in 1949, and the Government Boarding School shut its doors in 1955.

Boarding schools today

Off-reservation schools dwindled as well, but a number survived, including Chemawa, in Oregon; Haskell, in Kansas (now a college); and Sherman Indian School, in Riverside, CA. In many reservation families, successive generations have availed themselves of parochial or government boarding schools, though younger family members say their grandparents rarely talk about the experience. The option comes up, though, when a child has problems or isn’t performing well.

“In junior high, I wasn’t making good decisions for myself,” recalled Millie Friday, who runs the White Buffalo Youth Prevention program at Ethete on the Wind River Reservation, “so my dad just told me, he said, ‘You can go to Lander Valley High School, or you can go off to boarding school.’ I chose boarding school.”

The boarding schools of today are a far cry from Carlisle, though they still suffer from chronic underfunding. Recent interviews with Wind River youth at Sherman Indian School, in Riverside, Cal., revealed a variety of reasons for their being there. Some wanted a fresh start after getting in trouble on the reservation; some had lost parents or had other family problems; some just wanted a change, closer to a big city like Los Angeles; and some thought the school gave them a better shot at college.

The Sherman campus is a sprawling, fenced enclave with abundant athletic fields and some striking artwork by students decorating the walls and grounds. There is a weekly pow-wow, regular sweats, and native language instruction, as well as college counselling and a robust vocational program with hydroponic gardening and industrial arts. But budgetary problems depress teacher pay, curtail mental health counselling, and hamstring course offerings (the only native language taught is Din’e, the Navajo tongue, despite dozens of tribes represented in the student body).

One Wind River boy, about to graduate after spending only his senior year at Sherman, struggled to describe his loneliness during a recent interview, but stood by his decision to board. “I was moving with some bad influences back home,” he said, and then smiled shyly when asked how his grandparents would feel when they came to his graduation. Soon he would return to his reservation, intent on following a better path. A Bureau of Indian Education official, monitoring the interview, came up to him afterward and offered to write college letters of recommendation.

His grandparents, and other older reservation residents, know of the darker experiences of their predecessors at boarding schools, and the emotional remoteness that they inherited. There is debate in Native American communities about whether that boarding school legacy has left scars deep in their DNA; groups like the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition have campaigned for “truth and reconciliation” efforts in the United States, to acknowledge the historical trauma of the boarding school era.

“As educators and families from this (Wind River) community we are dealing with the effects in the form of generational and historical trauma,” said Lynnette St. Clair, Indian education coordinator in the Fort Washakie, Wyo., schools. “It’s not a pleasant place to be.” St. Clair is one of many educators who are trying to incorporate traditional tribal values – particularly respect – into curriculum, but with the difficult twist of filtering those values through the new technology that young people use.

In 2017, elders and youth from the Wind River Indian Reservation, including relatives of Horse, Little Plume and Little Chief, traveled to the Carlisle Barracks. Yufna Soldierwolf, a Sharp Nose descendent, had led a persistent campaign by the Northern Arapaho Tribal Historic Preservation Office to bring the remains of the boys home. After years of resistance, the U.S. Army relented.

Nelson White, one of the elders who traveled to Carlisle, said the decision to move them was fraught, but “their spirits were still here roaming around looking for help, so this is the way I take it, we’re here with these children. They’re still roaming around. With all this noise. I think it would be better for them to be back home.”

And when hundreds of tribal members gathered as rider-less horses brought the boys to their resting places at Wind River, White was thinking of an awakening for contemporary youngsters. “Maybe we can use this here as a light being turned on…Maybe the kids will listen to us. Help us along. Get our language back and our secret ceremonies.”

Resources

Primary sources

Archival Collections

- Carlisle Barracks Inventory – Volume 1, Manuscripts. U.S. Army Military History Institute, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA.

- “Carlisle Indian School History”, Cumberland County Historical Society. Oral histories, government reports, correspondence, and an extensive photo collection on the Carlisle Indian School, some of which can only be accessed at the society’s office in Carlisle, Pa., accessed May 23, 2019 at www.Carlisleindian.historicalsociety.com/resources.

- “Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center”, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa. Another extensive archive of Carlisle related material, collecting publications, administrative papers, recordings, and photographs from a variety of sources, most of it accessible digitally, accessed May 23, 2019 at http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu.

- “From Trout Creek to Gravy High: Boarding Schools at Wind River.” An on-line exhibit at the Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. A largely anecdotal history of boarding schools on the Wind River Indian Reservations, using taped interviews now held at Central Wyoming College in Riverton, Wyo., accessed May 23, 2019 at

- https://jacksonholehistory.org/from-trout-creek-to-gravy-high-boarding-school-experience-at-wind-river/.

- “Remembering Our Indian School Days: The Boarding School Experience.” Exhibit, Heard Museum, Phoenix, Ariz. Heard also has an extensive collection of documents and photographs related to boarding schools, focused on the Southwest. The call number for the exhibit materials in the Heard archives is RC 125. www.heard.org/exhibits/boardingschool.

- Record Group 75 – United States National Archives, Suitland, Md. Records of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs hold records of Carlisle Indian School and other federally funded Native American boarding schools. Most of the records relate to individual students; the records are otherwise fragmentary. Some of this material is summarized in an unpublished dissertation by Carmelita Ryan, “The Carlisle Indian Industrial School”, Georgetown University.

Reports

- Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, U.S. National Archives, accessed May 23, 2019 at http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=browse&scope=HISTORY.COMMREP.

- “The Problem of Indian Administration” (1928). Sometimes called “The Meriam Report”. A study of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from the Institute for Government Research (later to become the Brookings Institution) with a lengthy section on Indian education, accessed May 23, 2019 at https://www.narf.org/nill/resources/meriam.html.

- “Indian Education: A National Tragedy – A National Challenge” (1969). Sometimes called “The Kennedy Report.” 4,500 pages of testimony and documents about the state of Indian education compiled for the Senate Special Committee on Indian Education, a subcommittee of the Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED034625.pdf.

Interviews

Interviews quoted in this article were conducted by Caldera Productions, of Lander, Wyo., for the documentary “Home from School”, scheduled for release in fall, 2019, and are used by permission:

- Dr. Tsianina Lomawaima, Tucson, AZ

- Nelson White, Wind River Indian Reservation.

- Phyllis Gardner, Wind River Indian Reservation.

- Dr. Jacqueline Fears-Segal, Carlisle, PA.

- Millie Friday, Wind River Indian Reservation.

- Yufna Soldierwolf, Wind River Indian Reservation.

- Michelle Hoffman, Lander, WY

- Lynette St. Clair, Wind River Indian Reservation

Secondary sources

- Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875-1928. Lawrence, KA: University of Kansas Press, 1995. The most definitive book to date on the history of Indian boarding schools in the United States, with a focus on Carlisle.

- Bear, Charla. “American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many.” National Public Radio, May 12, 2008. www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1651865.

- Child, Brenda. Boarding School Seasons. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

- Drake, Kerry. “Estelle Reel, First Woman Elected to Statewide Office in Wyoming”. Wyohistory.org, accessed May 23, 2019 at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/estelle-reel.

- Fowler, Loretta. Arapaho Politics, 1851-1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

- Hipp, Martha. Sovereign Schools: How Shoshones and Arapaho Created a High School on the Wind River Reservation. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2019

- O’Gara, Geoffrey. “Home from School.” Wyofile, Sept. 1, 2017, accessed May 23, 2019 at www.wyofile.com/home-from-school.

- Yager, Sarah. “Making New Promises in Indian Country” The Atlantic, March 23, 2012.

- Pratt, Henry. Battlefield & Classroom, Four Decades with the American Indian. Edited by Robert Utley. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

- Stamm, Henry E. IV. People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825-1900. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

- Yager, Sarah. “Making New Promises in Indian Country” The Atlantic, March 23, 2012, accessed May 23, 2019 at www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/03/making-new-promises-in-indian-country/254969.

Illustrations

- The photo of the students in traditional dress at Carlisle was taken by the photographer John Choate, who died in 1902. Thanks to the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center at Dickinson College for information on the photographer.

- The photo of the larger group of schoolboys with Sherman Coolidge and John Roberts is from the Baker & Johnston Photographs Collection at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming; the 1911 photo of the Shoshone girls is from the John Roberts papers at the AHC and the photo of the people at St. Stephens is from the AHC’s St. Stephens Mission photo file. All are used with permission and thanks.

- The J. E. Stimson photo of the U.S. government boarding school at Fort Washakie—"Gravy High”—is Stimson negative 660 from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The Joseph K. Dixon photo of the unnamed schoolboy in uniform is from the collections of the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum in Casper. Used with permission and thanks.