- Home

- Encyclopedia

- William Jefferson Hardin: Wyoming's First Black...

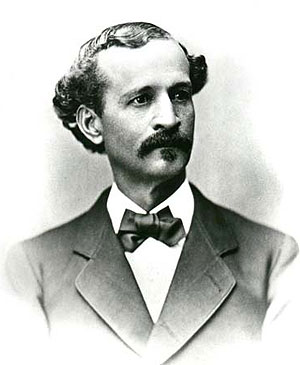

William Jefferson Hardin: Wyoming's first black legislator

Old West adventurer, orator, barber and reported bigamist, William Jefferson Hardin was Wyoming’s first African-American legislator in its territorial days.

Hardin served two terms in Wyoming’s Territorial Legislature, first in 1879, and again in 1882. He was the only member to serve in both the Sixth and Seventh Legislative Assemblies, and the only African-American to serve in the Wyoming Territorial Legislature.

His impressive public speaking skills gained him positive recognition in both Wyoming and Colorado territories, but personal scandals plagued him throughout his adult life.

Hardin was born in Russellville, Ky., in 1831. His father was white and his mother was a free woman who had one black parent. Their son was light-skinned, and claimed to be the nephew of a well-known Kentucky statesman, Benjamin Hardin, but this was never proven. Raised by Shakers in Bowling Green, Ky., in 1849 he began teaching “free children of color” and about that time married a slave named Caroline. Sometime after 1850, he headed to California, seeking his fortune in gold.

There was no mother lode for Hardin. After prospecting for five years in the gold country, he traveled to several states and Canada and eventually moved to New Orleans, La. He began service as a second lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guards in December 1862, in the Union Army but working mostly as a sugar cane harvester. Racial tensions ran high during those Civil War days, and the regimental commander who allowed blacks to serve was dismissed. The new commander did not want blacks in the regiment. Much bitterness ensued. In February 1863, the blacks resigned en masse.

Apparently leaving his wife and family in Kentucky, Hardin again went West and spent the next decade working mostly as a barber in Denver, Colorado Territory. He became well-known for his oratorical skills, which he employed in advocating equal rights for blacks, supporting public school integration, and black suffrage. An 1861 territorial law, interpreted liberally, allowed blacks to vote, but an 1864 amendment prevented them from doing so. In 1865, Hardin requested a public equal rights debate with two candidates for Congress. His persuasive oration caused one of the men to reverse his position and support black suffrage. In 1870, the nation ratified the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which guaranteed the right to vote to all men, regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Hardin was named delegate-at-large from Colorado Territory to the Republican national convention in 1872. In 1873, influential supporters helped him obtain a job weighing gold at the United States Mint. He married a white milliner, Nellie Davidson, that year.

That summer, his personal life changed. In July 1873, Caroline K. Hardin arrived in Denver, claiming W. J. Hardin was still married to her and that they had a daughter. She also accused him of having been a draft dodger during the Civil War. Hardin did not deny the charges. He argued that because he had been a minor at the time of their wedding and she had been a slave, their marriage was not valid.

He was not formally charged with bigamy, but he lost his job at the mint. While Hardin believed racial prejudice led to his dismissal, Director of the Mint Chambers C. Davis countered that Hardin was unqualified for his job.

Hardin and Nellie moved to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, where he opened a barbershop. The fate of Caroline and her daughter is not well documented.

Hardin once again gained recognition as a fine speaker and was often invited to address public meetings. In 1879, he was one of the men elected on the Fusion ticket to represent Laramie County in the Sixth Territorial Legislative Assembly. (The Assembly was the lower house, the Council the upper house of the legislature.) Fusion, a controversial practice, allowed Democrat and Republican delegates from the conventions of both parties to select the county’s legislators rather than allowing voters that privilege. Because fusion sparked controversy, a second “Workingmen’s convention” was held. Hardin attended but did not speak until invited to do so. He was nominated on both tickets and received 988 total votes, winning a seat with the third highest vote total.

On the opening day of the legislative session, which ran from Nov. 4 to Dec. 13, 1879, he introduced newly elected Speaker H. L. Myrick to the assembly. Hardin served on two relatively minor committees, the Indian and Military Affairs committee and a two-member Joint Standing Committee on Printing. It is unknown whether he chose these positions or was simply not offered better assignments.

During this term, Hardin introduced six bills, two of which were enacted into law. One was “to protect dairymen,” and the other “to protect poultry.” The poultry bill set a twenty-five cent bounty on chicken hawks and passed unanimously in the House. The Council added an amendment to include eagles.

The Sixth Assembly changed meeting dates of legislative assemblies from November of odd-numbered years to January of even-numbered years, beginning in 1882. Regular general elections were held in November of even-numbered years, creating a fourteen-month gap between election and service, which continued until Wyoming became a state in 1890.

Hardin was nominated at the 1880 Laramie County Republican convention for a seat on the Council but he finished low on the ballot and declined the opportunity to run. He had received enough votes, however, and he was nominated. Although he asked that his name be withdrawn, possibly because traditions of the time dictated that members serve a single term, delegates refused. Hardin was elected in November.

During the Seventh Assembly, January 10-March 10, 1882, Hardin introduced three bills. Two became law. One expanded the city boundaries of Cheyenne and the other made it a misdemeanor to use weapons in a threatening manner except in cases of self-defense.

He also supported a bill requiring the closure of barbershops on Sundays. This bill was considered too restrictive by other barbers, and Hardin was criticized because he asked another legislator to introduce the bill.

Hardin also supported a law allowing interracial marriage. In 1869, Wyoming Territory had enacted a law making interracial marriage a crime, but Hardin had not violated this law because he married his white wife outside of the territory. He did not seek a third term.

Although his term did not officially end until Dec. 31, 1883, duties of legislators did not include year-round meetings as is common today. He and Nellie sold their Cheyenne property in 1881 and 1882 and in 1882 moved to Ogden, Utah. He opened a barbershop there with partner David L. Lemon, but was once again beset by personal problems. Nellie eloped with another man.

In August 1883, he moved to Park City, Utah, where he operated still another barbershop. He was active in the Congregational Church and the Park City Liberal Party. His final public address, advocating party unity, was given at an 1887 event held for the Liberal candidate for Congress, John M. Young. Although Hardin made plans for a lecture tour, his health failed. He eventually sold his barbershop. He located Nellie in Seattle, Wash., in 1889 and learned she was a widow. He tried but failed to convince her to return to him.

Hardin ended his life by shooting himself in the heart in Park City on Friday, September 13, 1889. He is buried in an unmarked grave in the municipal cemetery.

Resources

Sources

- Berwanger, Eugene H. “William J. Hardin: Colorado Spokesman for Racial Justice, 1863-1873. The Colorado Magazine, Winter 1975, p. 55, 57, 61-63.

- Hansen, Moya. “Hardin, William Jefferson (1831-1889)” at BlackPast.org, accessed March 1, 2011 at http://www.blackpast.org/?=aaw/hardin-william-jefferson-1831-1889.

- Hardaway, Roger D. “William Jefferson Hardin: Wyoming’s Nineteenth Century Black Legislator,” Annals of Wyoming, vol. 63, Winter, 1991, pp.3-9.

- Kimball, Gary. “William Jefferson Hardin: A Grand But Forgotten Park City African American,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Winter 2010. pp. 23, 34, 35, 38, accessed March 18, 2011 at; http://utah.ptfs.com/awweb/guest.jsp?smd=1&cl=all_lib&lb_document_id=28914;

- Van Pelt, Lori. Capital Characters of Old Cheyenne. Glendo, Wyo.:; High Plains Press, 2005, pp. 52-55.

Illustrations

- The photo of William Jefferson Hardin is negative number 12976 from the Wyoming State Archives, used with thanks.