- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Teapot Dome, The U.S. Marines and a President’s...

Teapot Dome, the U.S. Marines and a President’s Reputation

Editor's note: This article was written by Carolynne Harris, consultant, in collaboration with and for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy.

Part 1 of 2 (Read Part 2 here)

In 1922, Wyoming was invaded by the U.S. Marines. Four marines, to be exact. They were dispatched by Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., and joined by a few officials of the Department of the Interior and some Denver newspapermen to remove—at gunpoint, if necessary—an oil prospector’s crew from U.S. Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3, better known then and now as Teapot Dome.

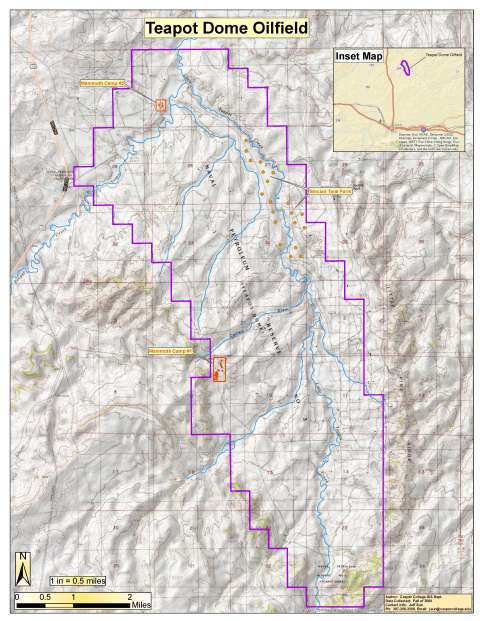

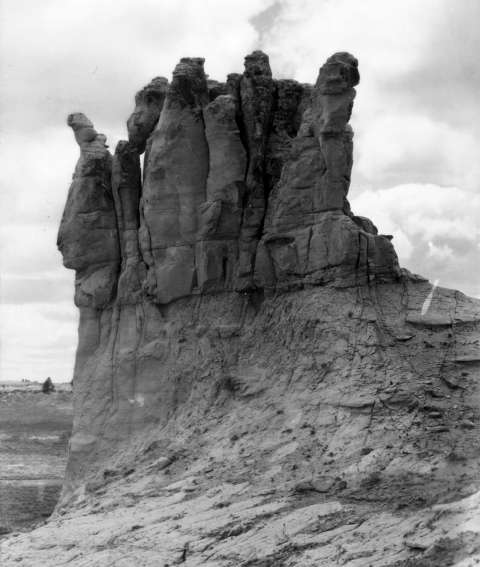

The Teapot Dome Oilfield lies in northern Natrona County, Wyoming, about 25 miles north of Casper. The field is six miles east of Teapot Rock, an eroded sandstone formation that formerly looked like a teapot. The rock is still easily visible from Wyoming Highway 259 about 12 miles south of the town of Midwest. Tornadoes and windstorms in the 1920s broke off what resembled a teapot’s handle and spout.

Early inhabitants

Before any prospectors sought their fortunes in the oil seeps, rocks, sage and dry creek beds around Teapot Dome, Native Americans lived and hunted in the area for millennia, and there is evidence of their use and occupation (e.g. rock shelters, cairns and hearths) in and around the Teapot Dome Oilfield. By the mid-1800s, conflicts with whites had broken out into sporadic warfare. The Bozeman Trail, a shortcut from the Oregon Trail along the North Platte River north to gold fields in Montana, became a focal point for conflict by 1865.

That trail cut northwest across the center of the Powder River Basin in what is now northeastern Wyoming—and across the northeast corner of the Teapot Dome Oilfield. The route was only used for a few years, however. Most of the traveling was done on the dry creek bed of Teapot Creek; no traces of the trail are present at the Teapot Dome Oilfield.

The oil companies start production

The first report on the potential for oil in the area was at nearby Salt Creek in 1886, which eventually led to the development of the Salt Creek Oilfield adjacent and north of the Teapot Dome Oilfield.

The town of Casper was established in 1888 with the completion of a spur of a subsidiary of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. The town was located on the former Oregon Trail, near where the Army had maintained a post at a bridge over the North Platte River decades earlier. Natrona County was formed in 1890 with Casper as its county seat. After oilfields were discovered, Casper became Wyoming’s largest oil refining center.

After 1900, oil began to replace coal as the fuel source for railroad locomotives, as well as for the engines that powered oil drill rigs and pumps. The Navy and Merchant Marines began converting ships from coal to fuel oil and setting up refueling stations at naval bases.

Based on the oil discoveries in the Salt Creek Oilfield and concerns about securing oil for the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of the Interior declared in 1909 that all unclaimed land around Salt Creek would be withdrawn—that is, that no new government land would be available for occupancy and/or mineral claims.

Unlike in the Eastern U.S., in the West, the federal government owned the majority of the land. The land and mineral-claims laws that existed for agriculture and for gold, silver and copper mining were extended to cover petroleum exploration and drilling. Legal disputes over the government’s withdrawal of the lands around Salt Creek led in 1920 to the passage of new laws regarding petroleum. Oil companies were allowed to lease federal lands for oil exploration, while the government retained surface rights.

Still, there was overproduction, waste and lack of storage. The government attempted to enact conservation measures, but oil companies were self-regulated. As a result, these measures were largely ineffective until 1931, when President Hoover required the oil companies to coordinate activities to reduce waste and rapid depletion.

Meanwhile, larger companies had been edging out smaller ones. By 1910, two main companies, the Wyoming Oil Fields Company and the Midwest Oil Company, were well established on the Salt Creek Oilfield. By 1912, each company had built a refinery in Casper and had laid pipe from the wells on Salt Creek to the new refineries.

By the end of 1913, the Midwest Refining Company had bought, swapped for, or absorbed enough of the other interests to become the biggest company on Salt Creek. Midwest owned mineral claims, producing wells, pumping stations, pipelines, storage tanks and refineries. Most of its workers lived along Salt Creek in the biggest of the camps—a town that would become Midwest, Wyo.

The Navy steps in

At the same time, the U.S. Navy was rapidly converting from coal to oil-burning ships, and concern arose over the Nation’s need for a secure domestic supply of oil in case of war or a national emergency. In response to this concern, the Pickett Act of 1910 authorized the U.S. President to withdraw large areas of potential oil-bearing lands in California and Wyoming—then the most active states for oil exploration on federal lands—as sources of fuel for the Navy.

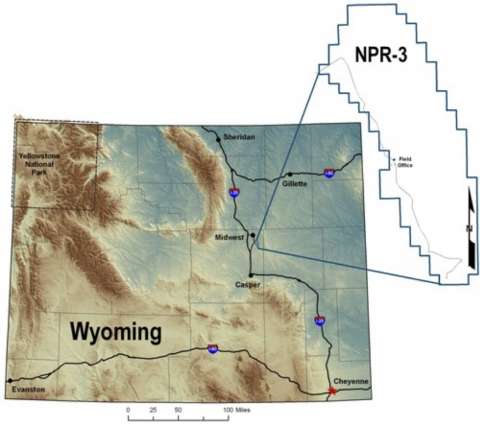

On July 2, 1910, President William Howard Taft set aside federal lands believed to contain oil as an emergency reserve for the U.S. Navy. This eventually led to an Executive Order by President Woodrow Wilson in 1915 designating the Teapot Dome area as Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3. NPR-1 and NPR-2 were in Elk Hills and Buena Vista Hills, California, respectively.

All but 400 of the 9481 acres of the Teapot Dome Oilfield were littered with private claims; however, many claims were invalid.

On May 23, 1921, President Warren Harding, by executive order, with the agreement of the secretary of the Navy, transferred administration of all naval reserves from the Department of the Navy to the Department of the Interior.

In 1921, Harding named New Mexico’s U.S. Senator Albert B. Fall, known as an opponent of federal conservation programs, the new Secretary of the Interior. Soon after taking office, Fall announced that the Naval Reserves would be leased for production in order to prevent private drillers on nearby claims from draining off the oil under the lands reserved for the Navy. Fall also argued that this would allow the Navy better access to fuel when needed, and that the Navy could trade the crude oil for refined fuel oil as necessary.

Fall leases the oil in a no-bid contract

In April 1922, Secretary Fall announced leases had been awarded for production of NPR -1 in the Elk Hills of California. He failed to announce, however, that on April 7, he, along with Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby had also awarded lease rights for NPR-3 at Teapot Dome to the Mammoth Oil Company—without competitive bidding.

Mammoth Oil Company was controlled by Harry Ford Sinclair, owner of the large Sinclair Oil Company. The lease allowed the government to keep 12.5 percent to 50 percent of the oil produced from each well. Mammoth was to construct oil storage tanks on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and to construct a pipeline from the Teapot Dome Oilfield to pipelines farther east.

The lease terms were intended to secure fuel oil and its storage for the Navy, with a sub-text of supporting the Navy in response to recent threats from Japan, to avoid loss of oil by drainage to adjacent wells and to create a more competitive market, thereby securing higher government royalties from the Salt Creek Oilfield.

Secretary Fall avoided the government’s problem of having to clear rights of the doubtful private claimants by requiring Mammoth Oil to do so before the contract was signed. A subsidiary of Midwest Oil Company, meanwhile, had gathered control of all the nebulous claims, and charged Sinclair and Mammoth $1 million to clear the lease.

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., sends in the Marines

An old friend and political backer of President Harding’s, James G. Darden, held claims on part of the Teapot Dome Oilfield that predated the Mammoth Oil Company lease by Harry Sinclair. Darden had entered the deal through the U.S. attorney general’s office, and in June 1922, he started drilling on land Secretary Fall had already leased to Mammoth.

When Fall, who despised Darden, discovered this, he demanded that Marines be sent immediately to Teapot to eject Darden’s “squatters.” President Harding wavered, but Fall pressed, and then spoke directly with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. and asked that the Marines be dispatched. Fall cited a non-existing legal precedent for this action.

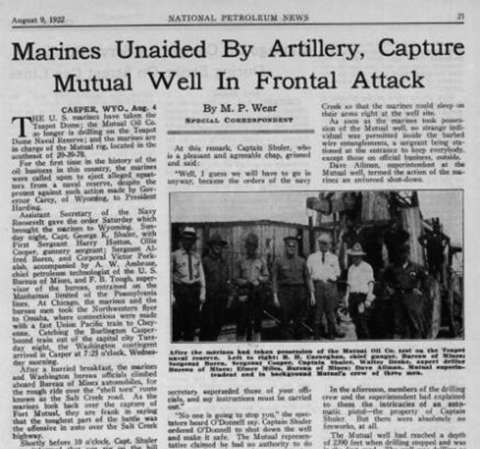

Roosevelt complied, and on July 29, 1922, Capt. George Shuler, four Marines and a geologist left Washington, D.C. for Casper. There they were joined by some Interior Department officials and reporters from the Denver Post. They proceeded north to section 30 of the oilfield, the section in dispute, where they arrived on the morning of August 1.

The Marines, armed with carbines, pistols and enough ammunition to take on a small army of oilmen, encountered a foreman, who, along with his supervisor, capitulated promptly.

After installing “No Trespassing” signs all over the rig, the Marines lunched with the foreman and supervisor, and that was it. It was, says historian Laton McCartney, the only time that a U.S. state had been ‘invaded’ by the U.S. Marines.

The lease hits the press

The invasion was not, however, the end of the drama of Teapot Dome.

In April 1922, prior to public knowledge of the lease agreement with Mammoth Oil, Leslie Miller, a Wyoming oil man, future Wyoming governor and a Democrat, asked Wyoming’s U.S. Senator John B. Kendrick, also a Democrat, to find out if leases were available for the Teapot Dome Oilfield.

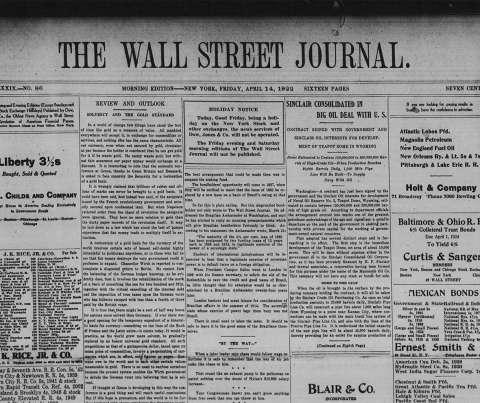

On April 14, the Wall Street Journal reported on the Mammoth Oil Company lease, noting government officials citing its advantages, but also revealing it was a non-competitive agreement. The newspaper seized on the lack of competitive bidding and implied that a conspiracy was underway between the Department of the Interior and the oilmen.

Senator Kendrick and Wyoming Congressman Frank Mondell, a Republican, asked President Harding that the lease be voided; Harding refused. Some oil producers were in favor of the agreement, assuming the pipeline being developed would be beneficial. As the arguments against the lease continued, Mammoth Oil moved forward with exploration and development of the Teapot Oilfield.

Mammoth develops the field

Harry Sinclair formed Mammoth Oil Company for the sole purpose of developing and operating the Teapot Dome Oilfield. Development came quickly, with multiple contracts to several drilling companies for the first round of wells. The company anticipated an output of more than 20,000 barrels per day. Sinclair’s contractors constructed more than 600 miles of pipelines to support anticipated production in Wyoming—including his interests at Salt Creek Oilfield—and to deliver the oil to the mid-continent trunk lines of both the Sinclair Pipe Line and Prairie Pipe Line companies near Kansas City.

About mid-May 1922, Sinclair Oil’s chief engineer arrived in Casper and immediately began inquiring for oilfield supplies and derrick lumber for 20 drilling outfits. By the end of the month, he had let contracts for 20 derricks, the drilling outfits had been shipped and construction had begun on a large tent camp, fleets of trucks were supplying the field from Casper “and the place generally represented an ant hill in point of activity,” writes historian Rear Admiral C.A. Trexel. To start drilling 20 new wells at once on a largely unproven oil reserve “raised public interest to a high pitch,” Trexel adds.

Most of the oilfield was developed between May 1922 and March 1924, and in May 1923 Mammoth Oil Company brought in a gusher. During the field’s development, crews established eight residence/operation camps, laid telephone and water lines, built roads and bridges, drilled natural gas and oil wells and installed tanks and pipelines throughout the field. When fully developed, the field included approximately 84 producing wells. Production peaked in October 1923 at 4,460 barrels per day.

By the summer of 1922, workers were living in 15 large tents with pinewood floors, pine tables and iron-frame beds. Permanent camps were completed in 1923.

Mammoth eventually developed four camps. They housed pump stations, dormitories, multi-room cottages, mess halls, classrooms and other support structures including tanks for oil. Sinclair, Houston, Chanute and Hardendorf companies also erected small camps on the field. Most of the Mammoth and Sinclair camps had water, gas, electricity and telephones, and the main Mammoth Camp had a sewer system. The other companies’ camps had just gas connections, with water available only from outdoor pumps.

The number of structures suggests Mammoth could house about 125 workers, providing family housing for 12 of the workers. The Sinclair Pipe Line Company could house approximately 25 more workers, assuming four rooms per cottage.

Congress and the courts intervene

Meanwhile, back in the U.S. Senate, Sen. Tom Walsh of Montana, a Democrat, was leading an investigation of the Sinclair-Mammoth lease. Walsh was suspicious of the lack of competition, of the lease’s origin in Secretary Fall’s office, and of Fall’s accelerated personal spending. Walsh was also concerned that the Navy’s previous policy of oil-reserve conservation had been so quickly reversed.

On March 13, 1924, Federal court-appointed receivers took control of the Teapot Dome Oilfield and stopped drilling operations but maintained production from existing wells. Drilling rigs were moved into storage at Casper, and many employees were laid off. At the time the receivers took over operations, 82 wells had been spudded in, and 60 wells were producing oil, gas, or water.

Years of argument in the courts and in public opinion continued. In October 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a U.S. Circuit Court decision that the Teapot Dome lease had been fraudulently obtained. The oilfield was officially turned back over to the Navy on January 7, 1928. Production was by then down to 730 barrels per day, and the Navy returned to its conservation strategy of storing the oil in the ground.

The Navy took steps to shut down the remaining wells and return the entire Teapot Dome Oilfield to conservation status. This resulted in the mudding and abandonment of almost all the oil and gas wells in the oilfield and the sale and removal of the infrastructure and camps. The shutdown and sales ended the initial development of the Teapot Dome Oilfield.

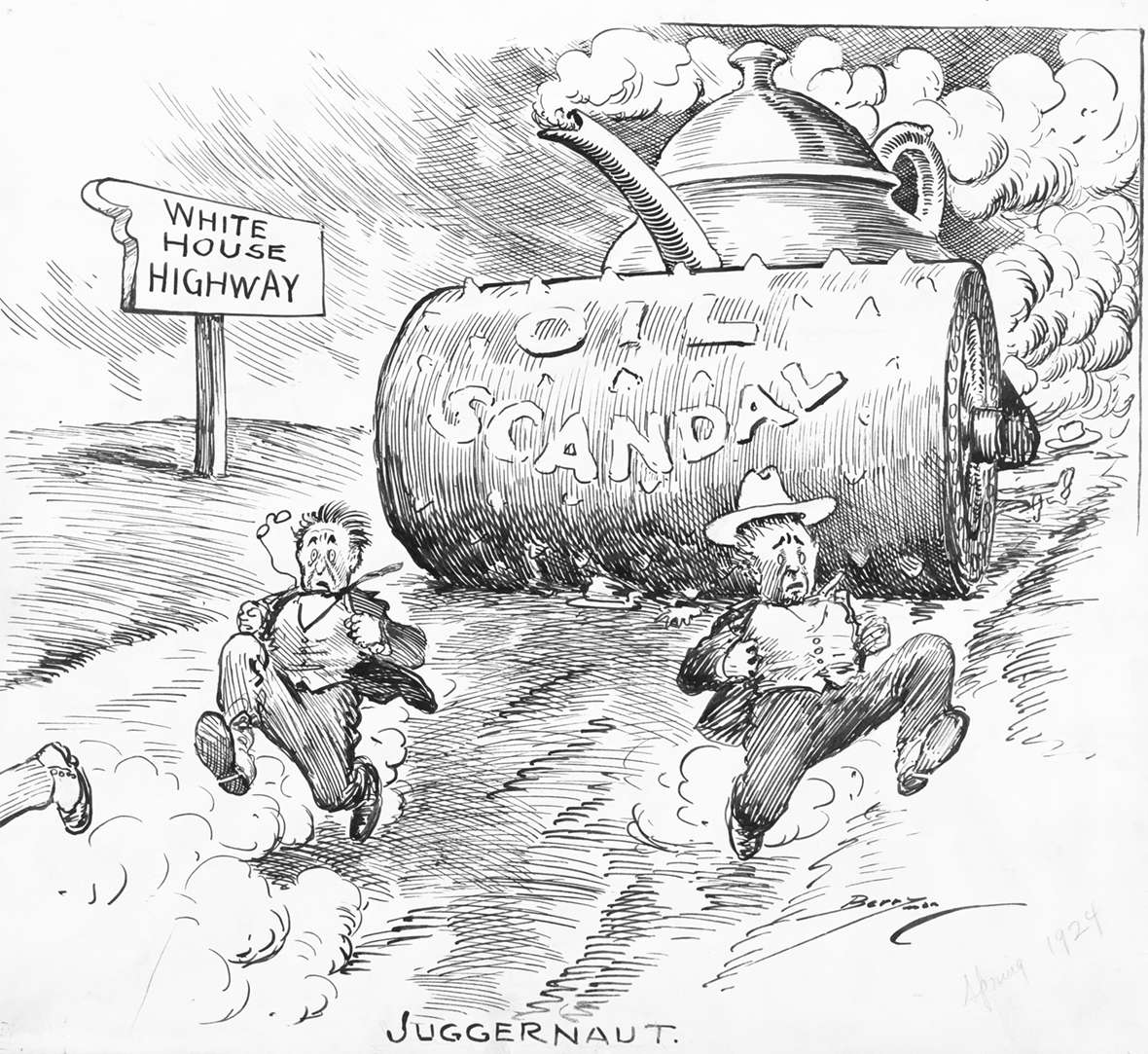

In October 1929, Fall was found guilty of criminal conspiracy, fined $100,000 and sentenced to a year in jail. Sinclair was also tried. Oddly, he was found not guilty of bribing Fall but was sentenced 6 ½ months for refusing to testify and for contempt of court. Edward Doheny, another oil man, was tried for giving $100,000 in loans to Fall, but even more oddly, was acquitted. This entire episode permanently damaged Harding’s reputation and contributed to his administration’s reputation as riddled with controversy and shady deals.

(Editor’s note: Publication of this and a companion article on the Teapot Dome Oilfield since the 1970s are supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy as part of the terms of the 2015 sale of the field to the private sector.)

Resources

- Darnell, J.L., Lieutenant Commander, U.S.N. “Report on Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3, (Teapot Dome), Natrona County, Wyoming.,” 1953.

- Fritz, John N., Ph.D. “Ethnographic Overview and Potential Traditional Cultural Properties Within the Teapot Dome Oil Field (RMOTC) North of Casper, Wyoming.” Report prepared for U.S. Department of Energy, 2007.

- Greer Services. “National Register of Historic Places Evaluation of Twenty-One Tank Rings Slated for Reclamation at the U.S. Department of Energy Rocky Mountain Oilfield Testing Center, Natrona County, Wyoming.” Casper, Wyoming, 2011.

- McCartney, Laton. The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding White House and Tried to Steal the Country, Laton McCartney, New York: Random House, 2008.

- National Petroleum News, July 3, August 9,1922.

- “Marines Unaided by Artillery, Capture Mutual Well in Frontal Attack.” National Petroleum News, Aug. 4, 1922

- Rea, Tom. “Boom, Bust and After: Life in the Salt Creek Oil Field.” WyoHistory.org, accessed March 21, 2016 at /essays/boom-bust-and-after-life-salt-creek-oil-field.

- Stubbs, Donna. “A Class I Cultural Resource Survey and Ethnographic Overview of the Rocky Mountain Oilfield Testing Center (RMOTC) and the Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 (NPR-3) in Natrona County, Wyoming.” ACR Consultants, Inc. Sheridan, Wyoming, 2013.

- Stratton, David Hodges. Tempest Over Teapot Dome: The Story of Albert Fall, Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

- Trexel, C.A., Lieutenant Commander, U.S.N. “Compilation of Data on Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 3 (Teapot Dome) Natrona County Wyoming,” 1930. Copies of cover sheet, table of contents and individual chapters available at U.S. Department of Energy.

- U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. “Teapot Rock” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form. December 1974, accessed March 21, 2016 at http://focus.nps.gov/pdfhost/docs/NRHP/Text/74002028.pdf.

- The Wall Street Journal, April 14, 1922, p. 1.

Illustrations

- The images of the newspaper clippings are courtesy of the author.

- The locator map and the photo of the rock cairn are from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photos of Teapot Rock and the string team are from the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The Clifford Berryman “Juggernaut” cartoon and the 1905 photo of Albert Fall by Harris and Ewing, photographers, are courtesy of the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the U.S. Marine is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The topographical map and animated flyover of the Teapot Dome field are courtesy of the Casper College GIS Department. Special thanks to Jeff Sun and his students.