- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Seminoe Cutoff and Sarah Thomas Grave

The Seminoe Cutoff and Sarah Thomas Grave

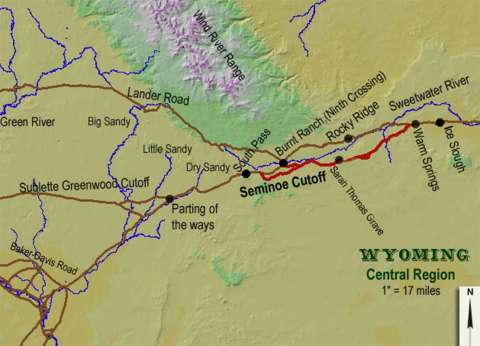

Among the many branches and variants of the Oregon Trail was the 35-mile Seminoe Cutoff, which allowed travelers to avoid the last four crossings of the Sweetwater River as well as the difficult climb over Rocky Ridge.

The cutoff was opened to wagons in the spring of 1853, after heavy snowmelt and heavy spring rains made the fords across the Sweetwater impassable well into the traveling season. The cutoff, combined with the use of the so-called Deep Sand Road that bypassed Three Crossings, enabled emigrants to stay south of the Sweetwater and avoid all the river’s fords except the first one—near Independence Rock. There, French-speaking traders with Shoshone families built a bridge across the river that lasted only until late June 1853, when it washed away.

In subsequent years, the cutoff was used at times of exceptionally high water or early in the season when the river was too high to be safely forded.

In a letter on June 1, 1853, Joseph Crabb wrote: “We started for the Sweet Water, a distance of 26 miles, got within two miles of the crossing, and stopped, finding the Sweet Water from 8 to 10 feet deep. Here we expected to be detained some days or weeks. I rode up to the crossing, and luckily found that there was a company of French traders encamped at Independence Rock, and lots of shanties. They came there early in the spring, and had built a bridge over this stream. It was just finished.”

Crabb’s company was to become one of the first to use the bridge and then the Seminoe Cutoff. Succeeding bridges at Independence Rock came and went as the years of the emigration passed.

The cutoff was probably named for Charles Lajeunesse, one of owners of the post at Devil’s Gate and likely one of the builders of the Independence Rock bridge of 1853. His nickname was “Semino.”

The cutoff commenced about seven miles west of Ice Slough. Warm Springs and Alkali Creek were passed on the way, but they only supplied poor, brackish water essentially unfit for use. The first good water on the route was at Immigrant Springs, as it is called now; in trail days it was called Rock Springs or Antelope Springs. The spring is about 15 miles west of where the cutoff leaves the main branch of the Oregon Trail and seven miles west of Alkali Creek.

A grave at immigrant springs

Diary and newspaper accounts show that there were emigrant deaths on the Seminoe Cutoff just as there were on the “old road,” as the main route was sometimes called, but existing identified graves on both routes are now rare. The only one that can be identified on the Seminoe is the grave of Sarah A. Thomas at Immigrant Springs.

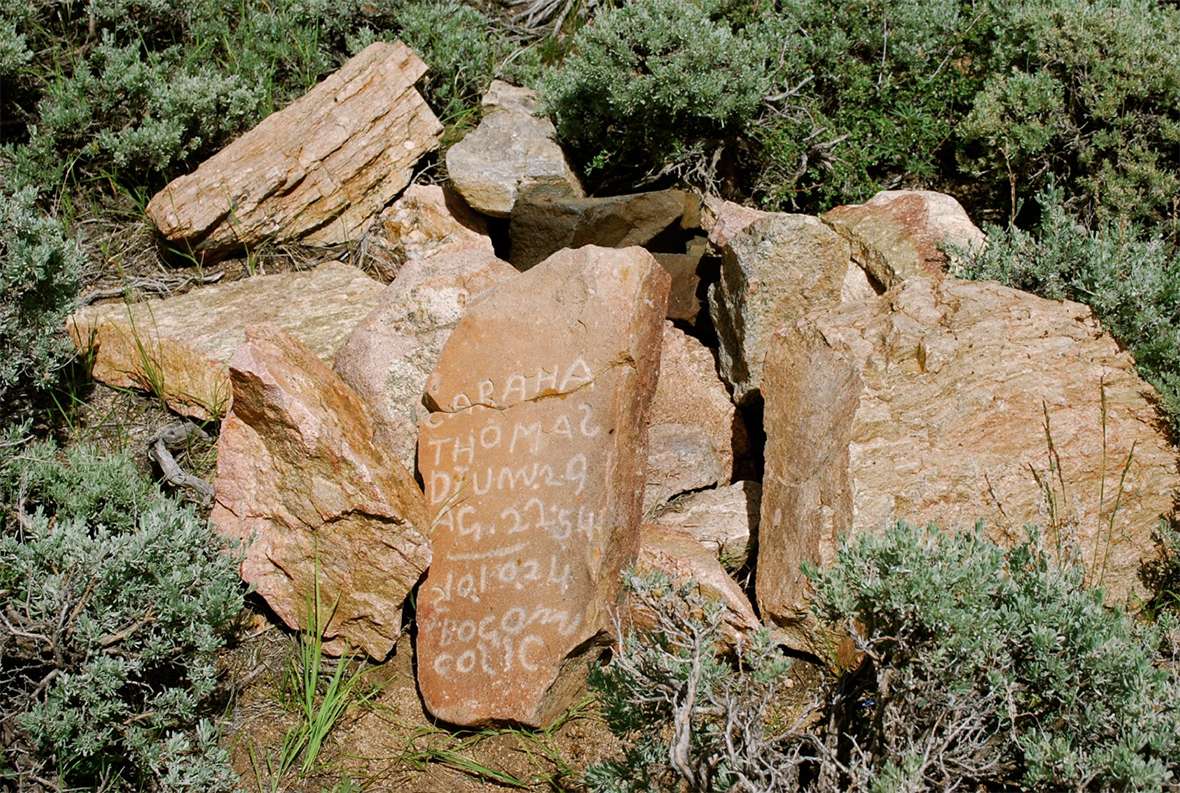

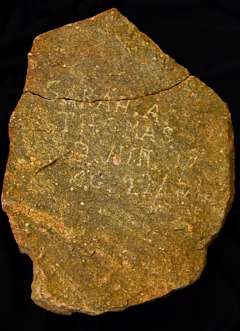

Nothing is known of Sarah Thomas other than the date of her death and age at the time, and these facts only because someone inscribed the information on her headstone. The epitaph reads: “SARAH A. THOMAS D. JUN 29 /54 AG. 22.”

One account survives of her burial, but it does not even include her name. Jacob Hays of Missouri was heading for California when his company reached the springs on June 29, 1854. He wrote: “Clear but very windy, traveled over some pretty rough roads some 13 miles, encamped for the night on Rock Creek [the runoff from Immigrant Springs]. Witnessed the burial of a lady, herded cattle some miles from the wagons to the left of the road where there is a noble spring. Spring near the road called Rock Spring.” That’s it, and it’s the only contemporary account of the life and death of Sarah A. Thomas thus far discovered.

The grave was covered over with large rocks collected from the surrounding hills, and a headstone was neatly inscribed and placed over the grave. Whoever Sarah Thomas was, her family and friends went on, likely to California or Oregon, and only Jacob Hays left us an account of her burial.

New stones in 1924

His is the last-known record of the grave until 1924 when it was re-marked by three newly inscribed stones. Two were left at the grave, and a third is now in the Pioneer Museum in Lander, as is the original. One of the two placed at the grave has since vanished completely. They are all dated Oct. 10, 1924, inscribed “10, 10, 24.” and all confirm what Jacob Hays had written, that Sarah A. Thomas died on June 29, 1854, at the age of 22.

These three markers include a cryptic postscript that proved difficult to interpret, as was the 1924 date. For years this postscript was a mystery to trail researchers, and several interpretations of what it says were suggested including “bacon colic,” as a possible cause of death, or “Bogan County” as her place of origin, but nothing really made any sense.

I now think the phrase is the name of the person who inscribed the three secondary markers, a Bogdan Cosic—the “S” is backwards—who, immigration records show, came to America in 1907 to settle in Rock Springs, Wyo. The immigration officials apparently spelled his name wrong: “Bogdan” instead of “Bogan.”

Cosic must have become a history buff, since it seems he went to the Thomas grave in 1924, collected the original marker, and left at least two of the replacements he had inscribed, signed and dated by himself, but all this is speculation. Emil Kopak of Oshkosh, Neb., photographed the grave and these two markers in 1930.

This convoluted story of Thomas grave markers received a happy ending when curator Randy Wise at the Lander Pioneer Museum rediscovered in storage what is assuredly the original headstone. The inscriptions on the replica markers were found to exactly match the inscription on the original grave marker, inscribed and placed over the Sarah Thomas grave on June 29, 1854. Whoever Bogan Cosic was, we owe him a debt of gratitude, along with the Lander Museum, for preserving this historic artifact.

Sometime early in the 1960s a ghoulish vandal desecrated the Sarah Thomas grave by digging up her bones, and leaving them scattered at the grave. It is not known if anything was taken, perhaps nothing. When Tom Bell, the curator at the Lander Museum at the time, heard about the vandalism, he organized a party that went to the grave where they collected the bones, reburied them, and replaced the rocks over the grave, including the remaining secondary headstone. Except for occasional visits by trail buffs exploring the Seminoe Cutoff, the grave has remained undisturbed ever since.

Resources

Sources

- Crabb, Joseph. Letter. The Alton Weekly Courier, Alton, IL, July 8, 1853, Vol. 2, #6, p. 3, 3, cols. 2-3.

- Hays, Jacob O., 1854. Diary- Lexington, Mo., to Sacramento, Calif., typescript, Acc. No. 543 Box 1, 10 p., American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie.

- Wise, Randy. “Emigrant Trail Grave.” E-mail messages to Randy Brown. November 17, 18, 20, 24, 29, 2015.

- Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. “Sarah Thomas Grave.” Emigrant Trails Throughout Wyoming. Accessed April 28, 2017 at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/trailsdemo/sarahthomas.htm.

- Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. “Cutoffs Seminoe.” Emigrant Trails Throughout Wyoming. Accessed April 28, 2017 at http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/trailsdemo/seminoecutoff.htm.

Illustrations

- The two color photos are by Randy Brown, and the black and white photo of the two headstones from his collections. Used with permission and thanks. The photo of the two BLM staffers at the Sarah Thomas grave is from the Lander Pioneer Museum. Used with permission and thanks. The map of the Seminoe Cutoff is from the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Used with permission and thanks.