- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Outlaw and His Lawyer: Butch Cassidy and Do...

The Outlaw and his Lawyer: Butch Cassidy and Douglas Preston

He was a member of Wyoming’s Constitutional Convention of 1889, a signer of Wyoming’s State Constitution, a member of the Wyoming House of Representatives and served two terms as Wyoming’s attorney general, but Douglas A. Preston is remembered for being the lawyer for Butch Cassidy, the outlaw.

An Outlaw’s Odyssey

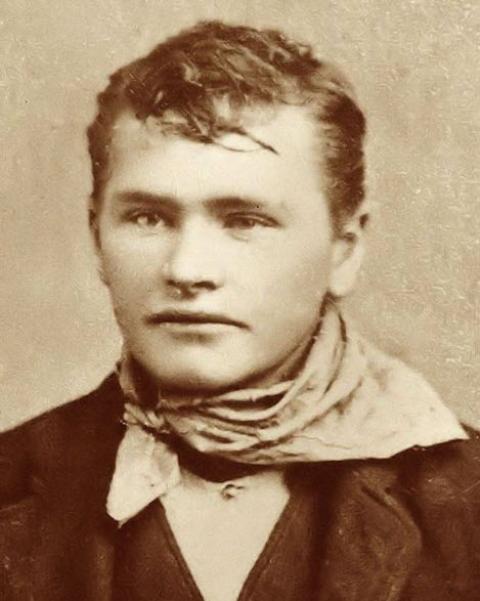

Robert Leroy Parker—better known later as Butch Cassidy—was born in Beaver, Utah, on April 13, 1866, where he lived for the first 13 years of life. The Parkers were a large, poor family, and in his teens Robert hired out to local ranches to provide extra income. At a ranch belonging to a man named Jim Marshall he encountered a small-time outlaw named Mike Cassidy, who became his mentor and introduced him to crime—intermittent livestock theft. Young Parker admired Cassidy, and later adopted his last name as part of his alias. (How he came to be called “Butch” is debated to this day, but “Butch” he became, and the name stuck.)

Parker/Cassidy left home in 1884 and for the next five years drifted through ranch jobs in Wyoming, Nebraska, Colorado, Montana and Utah. During this time he befriended two other cowhands and part-time thieves, Elzy Lay and Matt Warner.

On June 24th, 1889, Cassidy, Warner and Warner’s cousin, Tom McCarty, robbed the San Miguel Bank in Telluride, Colorado, of more than $20,000, launching Cassidy’s career as a professional criminal, which lasted until his (still disputed) death in Bolivia in 1908.

For the next 12 years, Cassidy led a loose network of notorious outlaws known variously as the Wild Bunch or the Hole in Wall Gang. (Hole in the Wall was a favorite hideout in Johnson County, Wyoming. So was Brown’s Hole—now called Brown’s Park—which straddles the Utah-Colorado border just south of the Wyoming state line, and so was Robber’s Roost in southeastern Utah.) Gang members included Harry Longabaugh—the “Sundance Kid”—“Kid Curry” and “Flat-Nose Curry,” (Harvey Logan and George Curry), Lay, Warner and Ben Kilpatrick, the “Tall Texan.”

Not long after the Telluride holdup, Cassidy surfaced in Dubois, in Fremont County, Wyoming, about 65 miles northwest of Lander, the county seat, where he met and partnered with a cowboy named Al Hainer on a ranch north of town. It is believed that the proceeds from the Telluride robbery financed the purchase. Affable as always, he made friends quickly, among them Lander banker Eugene Amoretti, Sr. Years later, Eugene Amoretti, Jr. said Cassidy deposited a great deal of cash in his father’s bank. “The cashier and I were sitting behind netting in the bank when a man came in. He threw a leather belt on the counter and said, ‘Count her out.’ The cashier took the belt and found the bills amounted to $17,500.”

Writing in In Search of Butch Cassidy, historian Larry Pointer noted, “Amoretti was probably the only banker in the West who could say Butch Cassidy was his friend. His bank in Lander was never robbed during the entire outlaw era.”

By the early 1890s, organized horse theft had become a highly lucrative epidemic and the Dubois ranch was likely a relay link in a rustling network. In 1891, Cassidy found himself entangled in a series of events that would land him in the Wyoming State Penitentiary, then located in Laramie. In the fall he bought three horses from a shady character named Billy Nutcher, whose story was that he had traded cattle for them the year before. Nutcher’s account did not hold up and, in any event, there was no bill of sale for the horses. Cassidy and Hainer were charged with grand larceny in Fremont County and became wanted men.

Lawmen, vigilantes, and range detectives hired by big ranchers like Otto Franc of the Pitchfork Ranch on the Greybull River near Meeteetse scoured the state for the pair, at first with little success. But in April 1892 a seven-man posse led by Uinta County Sheriff John Ward and Deputy Sheriff Bob Calverly tracked them to the little town of Auburn in Star Valley in far western Wyoming, about two miles east of the Idaho border. On April 11, Hainer was captured without incident, but Cassidy’s arrest was a different story. As Calverly described it later in a letter:

"I arrested Cassidy on April 11, 1892. I told him I had a warrant for him and he said: ‘Well get to shooting,’ and with that we both pulled our guns. I put the barrel of my revolver almost to his stomach, bit it missed fired [misfired] three times but owing to the fact that there was another man between us, he failed to hit me. The fourth time I snapped the gun it went off and the bullet hit him in the upper part of his forehead and felled him. I then had him and he made no further resistance.”

Cassidy and Hainer were taken first to the Uinta County Jail in Evanston, and from there to the Fremont County lockup in Lander. On July 15, 1892, both were formally charged in Fremont County with grand larceny “involving the theft of a horse valued at forty dollars from the Grey Bull Cattle Company on or about October 1, 1891.” District Court Judge Jesse Knight set bond at $400 each and both men were released pending trial.

Preston for the Defense

Due mostly to problems encountered in locating one prosecution witness and several defense witnesses, the trial was delayed for much more than a year. Cassidy retained Douglas A. Preston of Lander as his attorney; Preston would be assisted by C.F. Rathbone.

Born in Olney, Illinois in 1858, Preston was already a young attorney when he resettled in Wyoming in 1887, where he practiced law in Rawlins (1887-1888), Lander (1888-1895) and, beginning in 1895, in Rock Springs.

That Cassidy and Preston were friends is well established. According to a number of accounts, Cassidy and Preston met when Cassidy saved Preston from a beating in a saloon in Rock Springs. However, historian Bill Betenson, a noted authority on Butch Cassidy and author of Butch Cassidy, My Uncle and Butch Cassidy, The Wyoming Years, writes that “there is now a question on the veracity of this story. [Historian] Mike Bell has researched the source and says it originated with Pete Parker of Rock Springs, who has proven to be an unreliable source.”

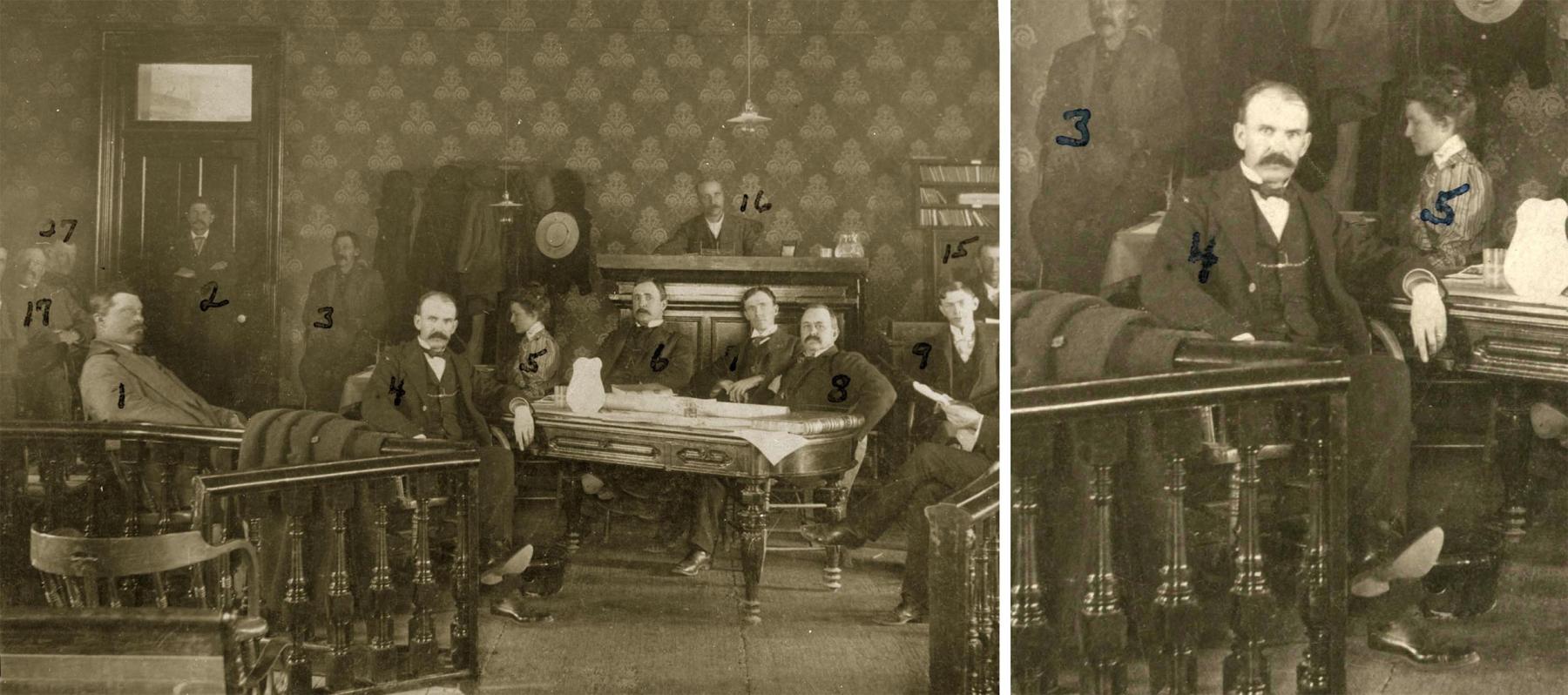

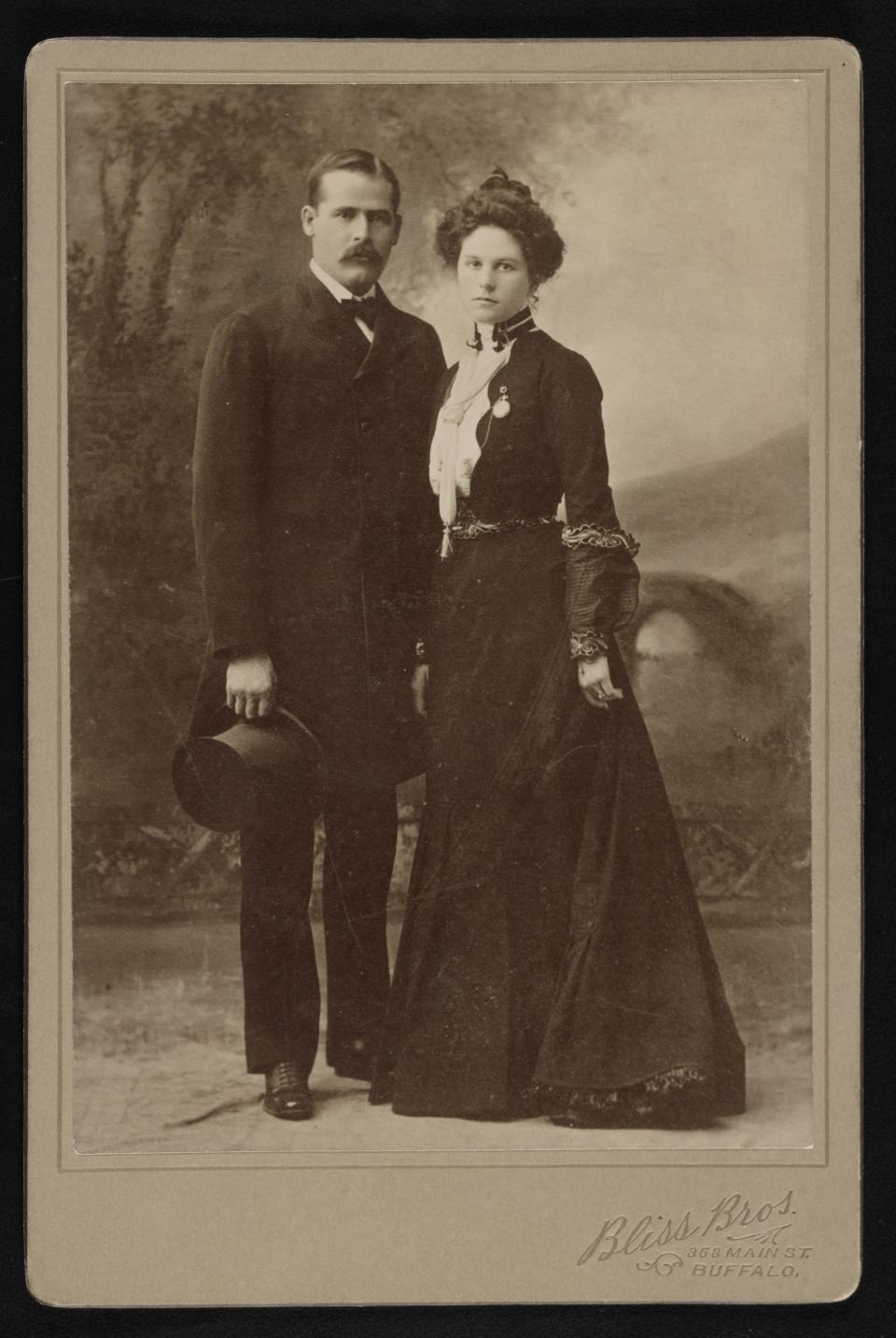

Image

However the two men met, court finally convened in Lander on June 20, 1893, with Judge Knight presiding. The trial was brief and the defense simple; Cassidy and Hainer did not deny being in possession of the horses, but maintained they’d bought them from Nutcher in good faith, unaware they were stolen. (Conveniently, though he’d been subpoenaed to testify, Nutcher did not appear at the trial. Nor did two men Cassidy claimed had witnessed the transaction.) The jury deliberated only a few hours before finding both men not guilty.

As the trial progressed and a “not guilty” verdict appeared likely, rancher Otto Franc filed charges against Cassidy and Haines in the theft of different horses in August of 1891, valued at $50. Both were re-arrested and were once again freed on bond.

The trial on the new charge opened on June 30, 1894. While Cassidy was found guilty, Hainer was once again acquitted. On July 10, Judge Knight sentenced Cassidy to two years at hard labor in the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Laramie.

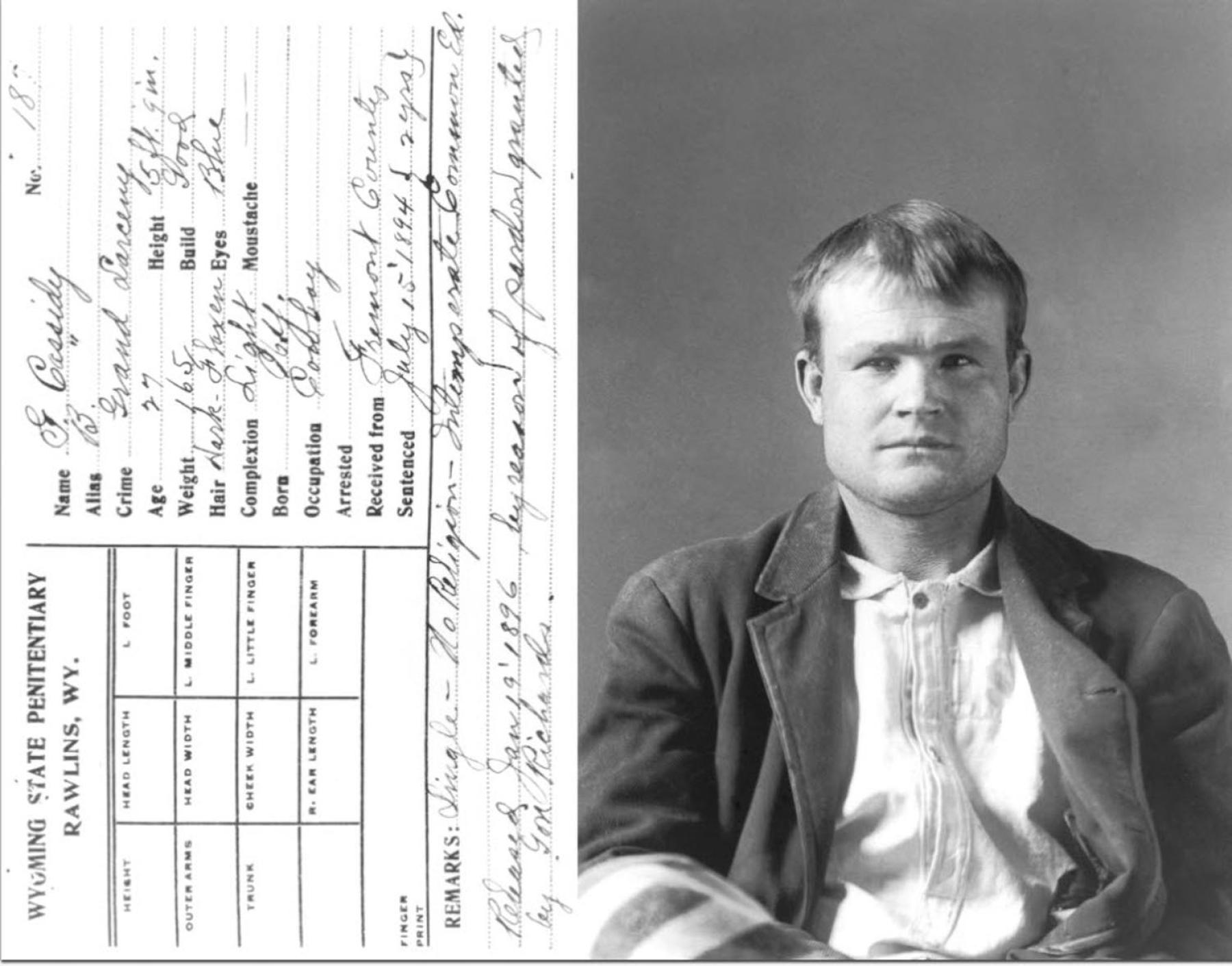

On July 15, Cassidy and five other Fremont County prisoners arrived at the prison, where he was booked in and assigned inmate number 187. There is no evidence that the next 18 months were anything but uneventful for Cassidy while he served his time, but that changed during the autumn of 1895 and early 1896.

A Plea for a Pardon

Judge Jesse Knight, who presided over both of Cassidy’s trials, had been impressed by his demeanor and behavior. This and an apparent twinge of guilt over what he felt to be procedural mistakes made in court compelled him to write a lengthy letter to Wyoming Gov. William Richards on Sept. 28, 1895, stridently requesting a pardon for Cassidy.

Attached to Knight’s letter was a hand-written endorsement of his pardon request, signed, interestingly, by the then-serving Sheriff of Fremont County, a former Sheriff of Fremont County, the Mayor of Lander, the Fremont County Treasurer, two Fremont County deputy sheriffs, the former Mayor of Lander, a state senator, the Lander city marshal and a member of the Lander City Council. Also advocating on Cassidy’s behalf was Uintah County Sheriff John Ward, who was present for his violent 1894 arrest.

Richards traveled to the penitentiary on Jan. 18, 1896, and met with Cassidy. Of the meeting, historian Betenson writes in Butch Cassidy, My Uncle: “Evidence exists that Butch did make some type of deal with the governor promising to commit no more crimes in Wyoming after his pardon.” Richards signed the pardon on Jan. 20. Later, he wrote that Cassidy “told me that he had [had] enough of Penitentiary life and intended to conduct himself in such a way as to not again lay himself liable to arrest." Cassidy was quickly released.

A Friend in Need

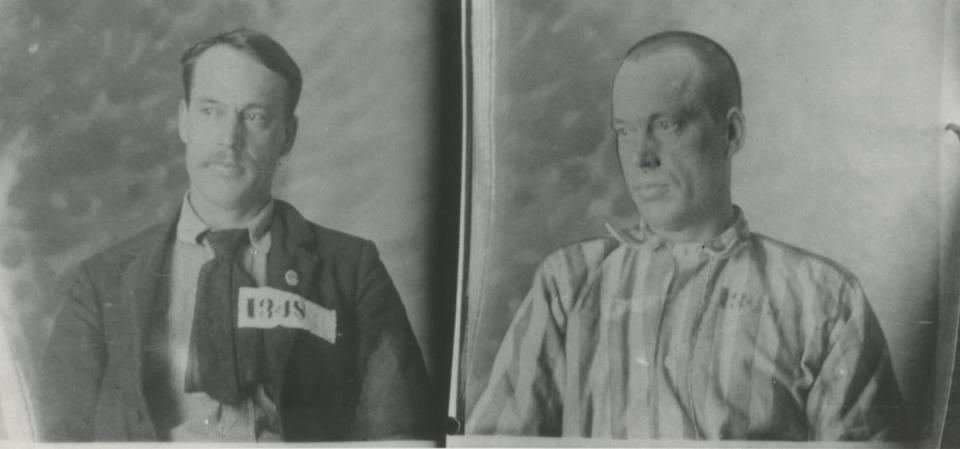

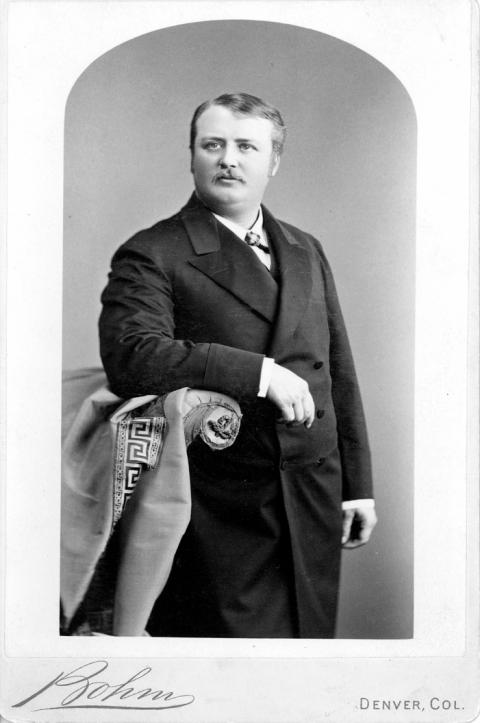

Image

In the spring of 1896—only months after Cassidy’s release—his friend and criminal cohort Matt Warner found himself in serious legal trouble in Uintah County, Utah. Warner and an associate named William Wall were arrested and charged with first degree murder in the deaths of two men in a gunfight in the mountains above Vernal, the county seat. They claimed self-defense; the two dead men, they said, ambushed them. Also charged was E.D. Coleman, a prospector who had hired Warner and Wall to protect his claims.

Uintah County (Utah) Sheriff John Pope decided to move Warner and Wall to the county jail in Ogden in Weber County as a security measure. There Warner was contacted by Cassidy, who offered to break him out. Warner advised against it, and as noted in an account by Cassidy biographer Richard Patterson, wrote back “Butch, we’re goners if we don’t get some money quick to hire lawyers.”

Image

It didn’t take long for Cassidy to devise a plan to “get some money quick,” as Warner put it. On Aug. 13, 1896 Butch, Elzy Lay, and a man named Bub Meeks robbed the Montpelier Bank In Montpelier, Idaho, and got away with some $7,000. (Lay was an old associate of Cassidy’s, and Meeks had a personal stake in the matter: his brother David was married to Wall’s daughter.)

As the Montpelier Examiner reported two days later:

“On Thursday afternoon, at 3:30 o’clock, while the citizens of Montpelier were quietly engaged in their usual daily avocations, three men, none of them masked, rode quietly down Washington Street to the Bank of Montpelier and dismounted. Cashier Gray and Ed. Hoover were standing in front of the building talking. One of the men invited them inside at the same time drawing a six-shooter. They did as directed, and when inside were told to stand with their faces to the wall and hands up. Two more men who happened to pass the bank door were also ordered in. Then one of the robbers went around behind the counter and held up Bud McIntosh, the assistant cashier, taking all of the money in sight and dumping it into a sack. Bud refused to tell where the greenbacks were and the man inside hit him over the eye with a gun. After ransacking the bank vault they went out, mounted their horses and rode off.

“The alarm spread quickly, and Deputy Cruikshank and Attorney Bagley were soon on the trail closely followed by Sheriff Davis when the robbery occurred, and a large posse.

“The robbers took the Canyon Road leading to Thomas’ Fork. When several miles away they changed horses and, crossing Thomas’ Creek, took to the mountains.”

Cassidy was the robber who pistol-whipped McIntosh. Inside the bank with him was Bub Meeks; Elzy Lay remained outside with the horses. The three fled east up Montpelier Canyon to their first fresh horse relay on Montpelier Pass. (Pre-staged fresh horses along a carefully planned escape route were a Cassidy trademark, and a wise one.) The pursuing posse, led by Bear Lake County Sheriff M. Jeff Davis, was soon outdistanced, and the three gunmen escaped into Wyoming, then south, almost certainly through Sweetwater County to Brown’s Hole.)

Warner and Wall’s trial opened in Ogden little over a month later, on September 8. They were represented by a squad of prominent, high-priced lawyers, D.N. Straup, Orlando Powers, F.L. Luther and by the attorney who arranged for their retainment, Douglas Preston, who by then had moved his practice to Rock Springs, Wyoming, in Sweetwater County.

A few days after Warner and Wall arrived at the Weber County jail in Ogden, as Cassidy historian Charles Kelly tells it:

"Douglas Preston of Rock Springs and Evanston, came to Ogden to assist in their defense. They then had an array of the best legal talent in the intermountain country. Preston brought with him his advance fee of $3,000 and enough more to furnish Warner and Wall with whatever luxuries they desired while awaiting trial. Warner bought a complete new outfit of clothes, including the best Stetson hat obtainable in Ogden. Preston left word with the jailer to get them anything they wanted. Butch Cassidy had made good his promise."

One day into the trial, on Sept. 9, the Salt Lake Herald devoted most of its front page to the trial, including a bombshell revelation:

"It has now come to light that the robbery [the bank in Montpelier] was committed for the purpose of securing money with which to defend Matthew Warner and his almost equally notorious associates, Walter Wall and E.D. Coleman, whose trial for the brutal murder of Richard Staunton and David Melton near Vernal last May is now pending in the Second Judicial District at Ogden."

The Herald article also declared that “Cassidy and his gang were camped outside Ogden waiting for an opportunity to rescue Warner and Wall.”

Not surprisingly, lawyers Preston and Powers emphatically denied the report and threatened to sue, but no suit was ever filed. Nor did the Herald ever retract its accusation.

Preston issued the following statement:

“I was employed last July, before the Montpelier robbery, and was paid at that time, but not by Wall . All this rot about receiving any money from the gang that robbed the Montpelier bank, after that robbery, is absolutely and unqualifiedly false. The statement that Cassidy and his gang are near Ogden or that he was engaged in the Montpelier robbery is also false. Cassidy is at this time in the town of Vernal and has been there for some time past. They say there is a reward of $2,000 for the capture of Cassidy. If any party will deposit $2,000 in any bank in Ogden or elsewhere, I will guarantee to deliver Cassidy to any part of the West within 48 hours.”

No one responded to Preston’s offer, and the trial continued. The jury found Warner and Wall guilty not of first degree murder, but of voluntary manslaughter. Coleman was acquitted, and Warner and Wall were sentenced to five years each at the Utah State Penitentiary. Warner was released after serving four years.

Another Holdup and a Misidentification

On April 27, 1897, Cassidy and Elzy Lay robbed the Pleasant Valley Coal Company payroll at Castle Gate, Utah, near Price, in east central Utah. of much more than $7,000 in gold, silver and currency. Cassidy was identified as one of the robbers in at least one newspaper account, and the company put up a $2,000 reward.

In May 1898, a sheriff’s posse pursuing stock thieves in Carbon County, Utah, killed two outlaws in a gunfight. One of them was identified as a bandit named Joe Walker, and the posse believed the other was Cassidy—a belief undoubtedly enhanced by the $4,500 reward posted by Utah Gov. Heber Wells for him and other Robber’s Roost men, plus the $2,000 offered by the Pleasant Valley Coal Company. After a hasty and impromptu inquest, both bodies were buried.

Word spread quickly that Cassidy had been killed, but confirmation was called for. Because of his background with Cassidy, Uinta County, Wyoming, Sheriff John Ward traveled to Utah. The body thought to be Cassidy’s was exhumed, and Ward confirmed that the man was definitely not Cassidy. (He was later identified as a Wyoming cowboy named John Herring or Herron.)

A Question of Ethics

Friendship is a fine thing, but there is a cloud over the ethics of Douglas Preston’s relationship with Butch Cassidy. Historian Richard Patterson imparts this account in Butch Cassidy - A Biography:

"Charles Kelly [another Cassidy historian] provides a footnote to the story, which, if true, places Butch’s Wyoming attorney, Douglas Preston, in a bad light. Kelly says that a mining entrepreneur named Finley P. Gridley [of Rock Springs, Wyoming] happened to run into Preston sometime shortly after the report hit the newspapers that Cassidy had been killed. According to Gridley, when he mentioned Butch’s death Preston threw back his head and laughed. When Gridley asked him what was so funny, he said that Preston replied, ‘Nothing much, except that I talked to Butch just before I left Brown’s Hole this morning.’

"If the story is true, Preston had met and conferred with a suspected criminal who was wanted by the law. Such conduct by an attorney, an officer of the court, though common in the West during the 1890s, was officially considered a criminal act in itself. This didn’t seem to bother Preston, however, and in later years he would brag about his meetings with Butch between holdups.”

Others write of these clandestine meetings, including Bill Betenson:

“Years later, Douglas Preston confided that he often met Butch in secret meetings in the desert between Brown’s Park and Rock Springs. Other reports indicate they would meet near Boar’s Tusk, north of Rock Springs.”

Wilcox and Winnemucca

At 2:18 AM on June 2, 1899, members of the Wild Bunch/Hole in the Wall gang robbed the Union Pacific Overland Flyer Number 1 train near Wilcox, Wyoming, in Albany County. While Cassidy is generally believed not to have been present for the robbery itself, it is safe to assume that he planned it.

Inside the express car was Express Agent Ernest Woodcock, who refused to open the car door. Dynamite was used to blow open the door, stunning Woodcock. The bandits helped him out of the car, then placed some 20 sticks of dynamite on and around the safe and set them off. The explosion blasted the car apart:

“The explosion completely wrecked the front end of the car, blowing off the roof and sides and demolishing most of the express matter. A hole about a foot in diameter was blowing through the top of the safe and the door was blown off.”

Traveling a short distance behind Overland Flyer Number 1 was another train. When the robbery commenced, a brakeman ran back to give warning, and the second train began backing up toward Rock River. Curiously, among its passengers was Douglas Preston. Finley Gridley of Rock Springs, who was also on the second train, reported that he encountered Preston there and Preston cried, “‘Don’t shoot, Grid! Don’t shoot! I can prove an alibi!’ Gridley said that he had the feeling that Preston knew that the train would be robbed that morning.”

In Butch Cassidy - A Biography, Richard Patterson writes:

"Around Rock Springs it was common knowledge that Preston was the Cassidy gang’s lawyer, and Gridley, who considered Preston a friend, was openly critical of him for maintaining such a close relationship with the outlaws, warning him that some people even suspected him of being a tip-off man for the Wild Bunch and that he was getting a share of the proceeds of the gang’s robberies."

Though it was initially reported that the bandits got away from Wilcox with $36,000 in currency and another $10,000 in diamonds, later the take was described as much higher.

The currency was, of course, damaged by the explosion and bore residue from the dynamite.

On April 29, 1900, Wild Bunch bandits Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan, Ben “The Tall Texan” Kilpatrick and William Cruzan robbed the Overland Limited near Tipton, Wyoming, of some $55,000. Dynamite was again used to open the safe, and the express car was blown apart. It is believed that Cassidy planned the holdup, as he had the Wilcox holdup.

(It was the Tipton robbery that inspired the scene in the 1969 film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman, that depicted the tremendous express train car explosion and featured character actor George Furth as Ernest Woodcock.)

In Winnemucca, Nevada, Cassidy, Longabaugh and Will Carver robbed the First National Bank of Winnemucca on Sept. 19, 1900, of a reported $31,640, mostly in gold, along with some $300 in currency. The bandits had arrived in the area around Sept. 9, camped around 10 miles from town, and spent the intervening 10 days casing the bank and planning their escape route. Despite intensive pursuit by posses, they made a successful getaway.

A month after the holdup, investigating lawmen located the robbers’ camp, where they found three letters torn into strips. George Nixon, the owner of the Winnemucca bank, pasted them together. They turned out to be correspondence with Douglas Preston, “dealing with attempts to launder some damaged loot from a prior robbery,” Bill Bettenson writes. One letter was on Preston’s letterhead:

Law Office

D.A. Preston

Rock Springs, Wyo.

8/24/1900

My dear sir -

Several influential parties are becoming interested and the chance of a sale are getting favorable.

Yours truly,

D.A. Preston

Image

The second letter, written by the same hand on plain paper with no letterhead, read:

"Send me at once a map of the country and describe as near as you can the place where you found that black stuff so I can go to it. Tell me how you want it handled. You don’t know it’s value. If I can get hold of it first, I can fix a good many things favorable. Say nothing to anyone about it."

The third letter was on different paper:

Riverside, Wyo.

Sept. 1st, 1900

C.E. Rowe,

Golconda, Nev.

Dear Friends -

Yours at hand this morning. We are glad to know you are getting along well. In regard to sale enclosed letters will explain everything. I am so glad that everything is favorable. We have left Baggs [Wyoming] so write us at Encampment, Wyo. Hoping to hear from you soon I am as ever,

Your friend

Mike

The Twilight of the Wild Bunch / Hole in the Wall Gang

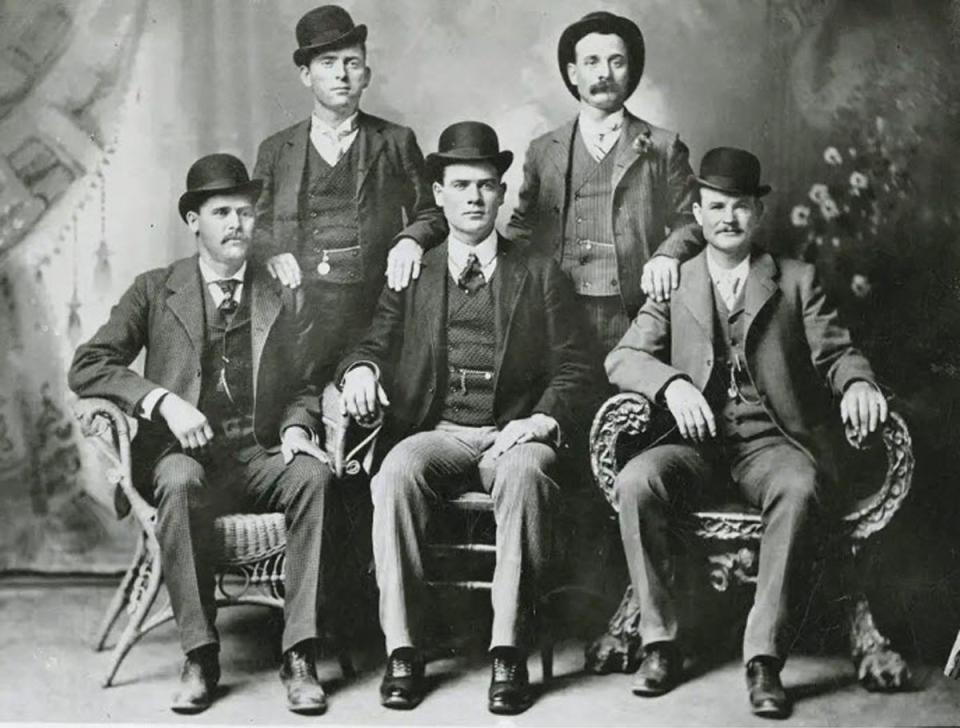

In November of 1900, five of the gang members—Cassidy, Longabaugh, Carver, Logan and Kilpatrick—traveled to Fort Worth, Texas, for something of a vacation. While there, they made a major mistake when they sat for a formal portrait. The Pinkerton Detective Agency learned of the portrait, obtained copies of the photo, and used the image to create top-quality wanted posters. The gang scattered to hinder capture.

The end was approaching for the Wild Bunch. On July 11, 1899, Elzy Lay, Sam Ketchum and two others robbed a train near Folsom, New Mexico, and got away with between $50,000 and $70,000. A posse that included Sheriff Edward Farr and United States Marshal Creighton Foraker located the outlaws in Turkey Creek Canyon and a gunfight ensued. Farr and another posseman were killed; Ketchum and Lay were wounded.

Ketchum was captured later and died of his wounds, but Lay escaped. He was arrested near Carlsbad, New Mexico, on Aug. 15. Lay was found guilty at trial and sentenced to life. He helped quell a prison riot, so in 1905, Gov. Miguel Otero reduced his sentence to 10 years and he was released on Dec. 15 of that year. After drifting around for several years, he settled in California, where he died of natural causes in 1934.

While rustling in Grand County, Utah, George “Flat Nose” Curry was shot and killed on April 17, 1900, by Sheriff Jesse Tyler. (In revenge, Sheriff Tyler, along with Deputy Sheriff Sam Jenkins, was killed the following month by Logan, who was also enraged by the death at the hands of lawmen of his brother Lonny in Missouri.)

On April 2, 1901, Carver was shot to death by lawmen in Sonora, Texas, when they moved in to arrest him on suspicion of murder. In 1904, Logan, who had robbed a Denver and Rio Grande train near Parachute, Colorado, killed himself to avoid capture as a pursuing posse closed in on him. (Logan was thought to be the worst of the Wild Bunch, having killed more than six lawmen and at least two other men.)

Ben Kilpatrick, veteran of the Tipton train robbery in Wyoming, went on to serve 10 years in prison for the robbery of a Great Northern train near Wagner, Montana, in July 1901. After his release, while attempting a train robbery in Texas in 1912, a Wells Fargo messenger named David Trousdale, who had been taken hostage, killed him. Trousdale managed to secrete an ice mallet and smashed a distracted Kilpatrick’s skull in with it, killing him instantly. With one of the guns Kilpatrick was carrying, he then shot and killed Kilpatrick’s accomplice, H. “Ole” Hobek.

Matt Warner’s post-outlaw life was colorful. After serving four years of his five-year sentence, Warner was pardoned by Utah Gov. Heber H. Wells and released in 1900. Afterward, he apparently became a respected member of the community, serving as a deputy sheriff, a detective and even a justice of the peace. In his later years he wrote a vivid memoir of his outlaw years, The Last of the Bandit Riders, and died of natural causes in Price, Utah, in 1938.

Cassidy, Longabaugh, and the mysterious Etta Place, who Longabaugh married, spent what was apparently a pleasant month in New York City, then sailed to Argentina, determined to start a new life as ranchers. By late 1905, though, it was back to a life of crime with a bank robbery in a town called Villa Mercedes, which netted them 12,000 pesos. Both men were identified, and the heat was on. Etta is believed to have returned to the United States alone, and the two men went to Bolivia, where they were reported killed in a gunfight with Bolivian authorities in San Vicente on Nov. 8, 1908. Their deaths—especially Cassidy’s—are a matter of debate to this day, and many believed he survived and returned to the United States.

A Distinguished Career

In 1889 Wyoming was still a territory, but the push for statehood was strong. Preston, then a young lawyer practicing in Lander, was selected as a delegate to the State Constitutional Convention from Fremont County, which opened in Cheyenne in September. Over the course of 25 days, the convention hammered out the state’s constitution, covering issues that included the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government, water law, coal, the railroads, labor, religion, political and sectional divisions and education.

Of prime importance was the provision that stated, “The rights of citizens of the State of Wyoming to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex. Both male and female citizens of this state shall equally enjoy all civil, political and religious rights and privileges,” reaffirming Wyoming’s adoption of women’s suffrage while still a territory, in 1869.

Among the delegates’ 45 signatures was Douglas Preston’s. The statehood bill was introduced in Congress on March 26, 1890, and passed both houses. President Benjamin Harrison signed it into law on July 10, creating Wyoming the 44th state.

After moving his practice to Rock Springs, Preston served in the Wyoming House of Representatives from 1903 to 1905. Gov. Joseph M. Carey appointed him attorney general of Wyoming in 1911, and four years later he was reappointed to the post by Gov. John B. Kendrick, who succeeded Carey. According to an account in Preston’s obituary, “ It is an accepted fact that he filled the office of the attorney generalship with distinction; and public opinion has accorded him front rank among those who have occupied the position.”

Later, he was elected to the Wyoming State Senate from Sweetwater County, and for a number of years was owner or part-owner of the Rock Springs Rocket.

Preston died on Oct. 20, 1929, as the result of an automobile accident on the Lincoln Highway west of Granger. Preston was not driving at the time of the accident. He never learned to drive; his wife Anna (she was his fourth) was behind the wheel, and the cause of the crash remains unclear. He was buried in Rock Springs on Oct. 24. A large crowd attended his funeral, including United States District Court Judge T. Blake Kennedy and Gov. Frank C. Emerson.

Butch Cassidy and Douglas Preston—An Assessment

Historian, writer and Butch Cassidy descendant Bill Betenson is unequivocal about Preston: “Douglas Preston was involved in laundering the damaged currency and continued to be suspected by the Pinkertons, but amazingly no charges or consequences came his way.”

His secret meetings with Cassidy while he was a wanted man were highly questionable and arguably illegal. His odd presence and behavior in the proximity of the 1899 Wilcox train holdup and, more significantly, the discovery of the cryptically worded correspondence from him so near the site of the Winnemucca bank robbery in 1900 cannot be readily overlooked.

And yet, aside from—and especially after—his association with Cassidy, Preston was, by all accounts, a sterling and civic-minded citizen and public official. Extensive research discloses not a whiff of impropriety or misconduct after 1900.

So what is the explanation?

The answer, many believe, was Preston’s friendship with the outlaw, and Cassidy’s affability and extraordinary talent for charming people. Of this there is abundant evidence, exemplified by his pardon following a personal meeting with Gov. Richards, the near-Herculean campaign for that pardon by the judge who sentenced him to the penitentiary in the first place, and the signed support for it expressed by so many Lander and Fremont County officials and former officials and others.

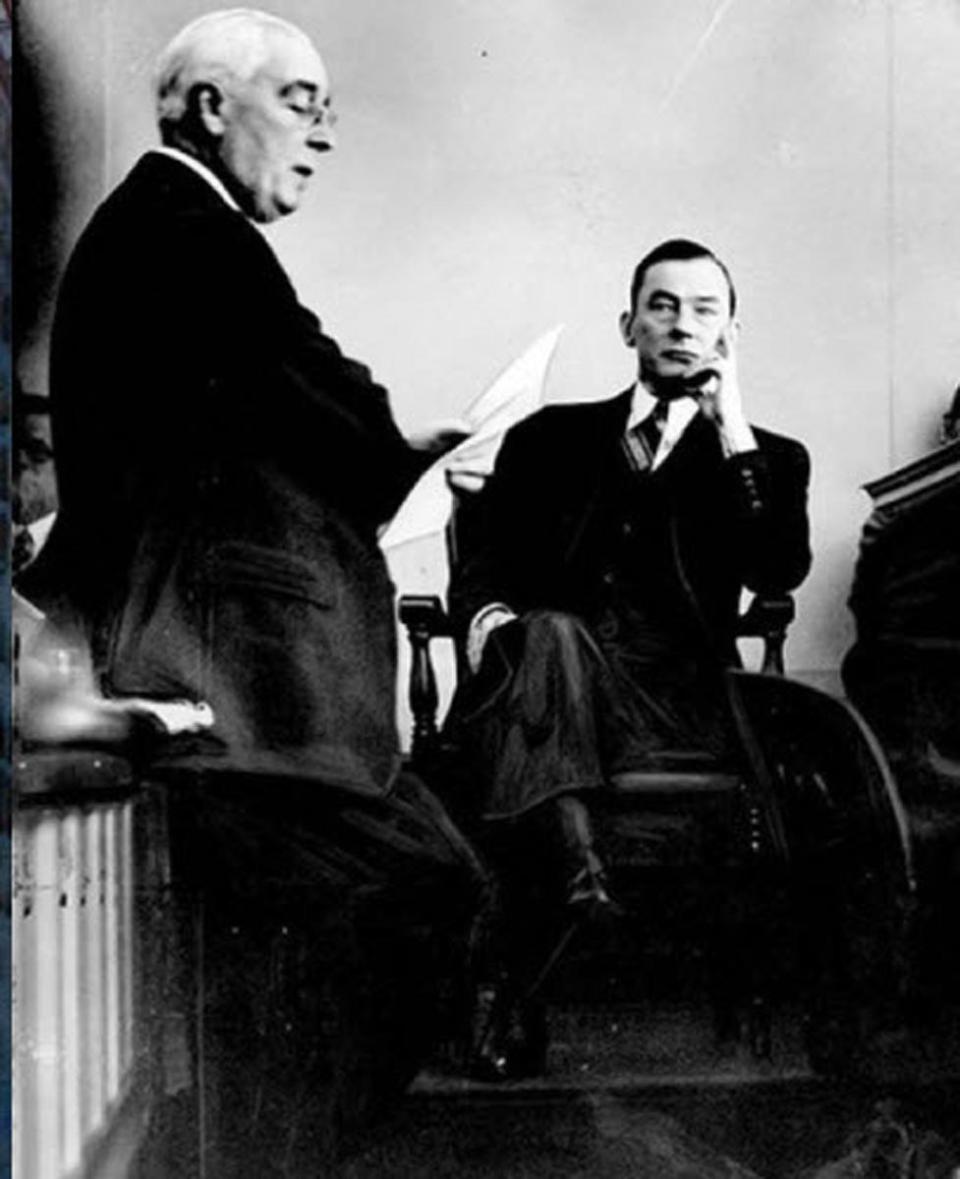

Image

Cassidy is not alone among the criminal charmers of history, who include Ted Bundy, Rodney Alcala, Andrew Cunahan and H.H. Holmes. But these men were serial killers, while Cassidy is believed not to have ever killed anyone. A more appropriate comparison might be James John Walker, known as “Beau James,” who was mayor of New York City from 1926 to 1932.

Jimmy Walker, a stalwart of New York’s Tammany Hall Democratic machine, was completely and unabashedly corrupt. An aide said that he would come into his office in the morning (his work hours were often between noon and 3:00) and see his desk covered with mail. He would ask, “Are there any checks in there?” and if the answer was no, he’d sweep everything onto the floor. But his wit, grace, and prodigious charm made him highly popular, and in his two political campaigns for mayor, he crushed his opponents. In the end, it was not the people who brought him down, but the Seabury Commission, (also known as the Hofstadter Commission ), a joint investigative committee formed by New York Gov. Franklin Roosevelt and the New York State Legislature, tasked with probing rampant municipal government corruption in New York City.

When Walker was obliged to take the witness stand, Judge Samuel Seabury, who led the Commission, cross-examined him. Seabury’s aides cautioned him, “He’s so charming. Don’t look him in the eye; he’ll charm you,” and he took their advice, standing sideways and seldom letting Walker catch his eye. But Walker’s luck had run out, as the Commission amassed evidence that he had collected nearly one million dollars in kickbacks. He resigned as mayor and sailed off to a grand tour of Europe with his mistress. He never faced charges stemming from his time in office, and died of a brain hemorrhage in 1946, age 65.

Charm has been defined as “an intangible quality that has the ability to attract and captivate others.” Charm is an important element of leadership, as evidenced by both Cassidy and Walker. Consider Cassidy’s dozen years leading the rough men of the Wild Bunch and his pattern of careful planning, resulting in successful robberies and getaways. As for Walker, despite his breathtaking corruption, he was known to be a highly effective city manager. As reported in Avenue magazine, “He invested in public utilities like waterworks and subway lines; created the departments of sanitation and hospitals, and greatly improved the city’s docks, parks, and playgrounds. Even critics had to begrudgingly admit he got things done.”

Whether or not Douglas profited from his dealings with Cassidy is unknown. But it seems clear that whatever actions he took likely arose mostly from friendship, not avarice. His decades of unblemished public surface after 1900 attest to that.

Editor's note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, whose support helped make the publication of this article possible.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Betenson, Bill. Butch Cassidy, My Uncle. Glendo, Wyoming: High Plains Press, 2012.

- ___________.l Butch Cassidy, The Wyoming Years. Glendo, Wyoming: High Plains Press. 2020.

- Bragg, Bill. “Prominent lawyer defended Cassidy.” Casper Star-Tribune, March 30, 1975, p. 13F.

- “Death Closes Career of Famous Wyoming Lawyer.” Rock Springs Rocket, Oct. 25, 1929.

- Peterson, C.S. Men of Wyoming. Denver, Colorado, self-published, 1915

Secondary Sources

- Adamson, Richard, and Simon Casson. Riding the Outlaw Trail, London: Eye Books, Ltd., 2004.

- Baker, Pearl. The Wild Bunch at Robbers Roost. New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1965.

- Boze, Bob. “Campfire Shoot-Out.” True West, Oct. 2, 2007.

- Buck, Daniel, Anne Meadows. “The Wild Bunch” True West, Nov. 1, 2002.

- Fowler, Gene. Beau James - The Life and Times of Jimmy Walker. New York: Viking Press, 1949.

- “Jimmy Walker May Have Been NYC's Most Corrupt Mayor, but Damn Was He Fun.” Avenue magazine, Dec. 2, 2021, accessed Jan. 11, 2022 at https://avenuemagazine.com/jimmy-walker-prohibition-era-new-york-mayor-notorious-new-yorker/

- Kelly, Charles. The Outlaw Trail - A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch. New York: Bonanza Books, 1959.

- Knight, Judge Jesse, letter to Governor William Richards, Sept. 28, 1895, Wyoming Postscripts Jan. 19,2016 at Wyoming State Archives, accessed Jan. 17, 2025 at https://wyostatearchives.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/on-this-day-in-wyoming-history-butch-cassidy-is-pardoned-1896/

- Patterson, Richard. “Butch Cassidy’s Surrender Offer.” HistoryNet, Jan. 29, 2024, accessed Jan. 11, 2025 at https://www.historynet.com/butch-cassidys-surrender-offer-2/

- Pointer, Larry. In Search of Butch Cassidy. University of Oklahoma Press, 1977.

- Warner, Matt, Steve Lacy, Joyce Warner. Last of the Bandit Riders . Revisited, Salt Lake City: Big Moon Traders, 2000.

Illustrations

- The photo and prison card of Butch Cassidy, the photo of Douglas Preston and others in the Sweetwater County courthouse, the photo of Matt Warner and the photos of Preston’s law office are all from the Sweetwater County Historical Museum. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of Elzy Lay is from the Utah State Historical Society. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Bub Meeks and the photo of the exploded express car are from the American Heritage Center. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the Fort Worth Five and of Harry Longabaugh and Etta Place are from the Pinkerton Collection at the Library of Congress—the Fort Worth Five via Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Judge Jesse Knight is from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of New York Mayor Jimmy Walker is an Associated Press photo via New York magazine. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Judge Samuel Seabury is from the New Yorker. Used with thanks.

- The death photo of Ben Kilpatrick and Ole Hobeck is from the National Museum of Crime and Punishment. Used with thanks.