- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Mathew Campfield: Barber, Coroner and Pioneer S...

Mathew Campfield: Barber, Coroner and Pioneer Survivor

In the third week of March 1936, laborers working to reconstruct old Fort Caspar dug up a set of human leg bones. Expert analysis, the Casper Tribune-Herald reported, would soon show whether the legs belonged to an American Indian or a White man, and the search for the rest of the skeleton would continue.

But Natrona County Sheriff Jack Allen was certain there was no need to look any farther. The legs “undoubtedly” belonged to Matt Canfield, Allen told the paper, “a Negro homesteader … whose legs were once amputated at the knees.” Canfield was a former slave who later became a barber in Casper, Wyo. He took out a homestead claim on land west of town near the North Platte River, where the old fort had been. Canfield’s legs froze one winter during a blizzard. After that, he got wooden ones, Allen said.

The paper chewed around on the question for two or three more days. There turned out to be bones of just one leg, not two. Humans have two leg bones below the knee; perhaps that was the source of the confusion. The leg, the paper decided, belonged to Louis Guinard, a trader who had built the bridge that crossed the river by the old fort more than 75 years earlier. One night Guinard had fallen off the bridge and drowned, and only his leg, still inside a boot, had been recovered. His Shoshone wife had supposedly mourned the leg for some time after the death. After that, she must have buried it. This solution to the leg-bone mystery was now “believed certain,” said the reports.[1]

The real Mathew Campfield

And what of Matt Canfield, the barber and homesteader? His name was in fact Campfield, and his first name was spelled more often with one T than two: “Mathew,” not “Matthew.” He was born into slavery in Georgia and served in the Civil War in the Union

Army in a regiment of Black soldiers recruited in Arkansas, the 57th U.S. Colored Volunteer Infantry. He enlisted in the fall of 1863 at Helena, Ark., and was mustered out with an honorable discharge after the war when the rest of the regiment was disbanded at Fort Leavenworth, in northeastern Kansas, in December 1866. In the Army he held the rank of musician and later principal musician—leader of the regiment’s band.[2]

Afterward, he ran a saloon for a while just off the military property near Fort Leavenworth and gave music lessons there as well. By January 1868 he was working in western Kansas as a servant to Col. Edward Wynkoop, Indian agent for the U.S. government to the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

Frozen feet

Campfield was driving a team of horses from Fort Harker to Fort Larned through a snowstorm on the night of January 8 and early morning of January 9. According to at least one account, he may have been one of a party sent into the snow to hunt deserters.[3] He got lost, and before he found his way to safety both feet were badly frozen.

Twenty months later, in the fall of 1869, an Army doctor named Alfred Woodhull found Campfield in the hospital at Fort Larned. He had lost parts of his feet from the freezing “and the stumps were imperfectly healed,” the doctor remembered 25 years later.[4] The doctor did a proper amputation, taking off both feet at the ankles, so that Campfield could later be fitted for artificial limbs. By 1870, the U.S. Census shows, Campfield was back in Leavenworth, working as a barber.

Barbering would have allowed him to make a living without having to move around much. Whether he sat on a tall stool to work or stood on his wooden feet all day isn’t clear. Years later friends remembered that he could “stump around on [his wooden legs and feet] but has to use a cane all the time.”[5]

Sometime in the 1870s, Campfield married Fannie Davis, who had been born into slavery in Missouri but spent the Civil War years in Texas, as her enslaver had shipped her and other enslaved people south, where they were less likely to be freed by Union troops. After the war she joined her mother in Leavenworth and got to know Campfield there. One document places their marriage at 1874, another at 1877. In any case, Fannie was certain, decades later, that it was 1879 when they left Kansas and came to Wyoming Territory.[6]

Territorial Wyoming

The 1880 census places Matt Campfield at Fort McKinney, Wyoming Territory, just outside the new town of Buffalo in Johnson County, working as a barber and living with Fannie, whom it lists as his wife. He was still there in the fall of 1882, when election records show that he ran to represent Johnson County in the Council, the upper house of the Wyoming Territorial Legislature. He received one vote.[7]

Fannie remembered years later that Matt ran the post barbershop and she worked for Col. Verling Hart, the post commandant, and later ran a restaurant for the officers. Then the Campfields moved to Laramie for a few months, and then to Rock Creek, a town about 45 miles northwest of Laramie and for a few years one of the main livestock shipping points on the Union Pacific Railroad. The place was lively, with at least one hotel and four saloons. Matt barbered. Fannie washed and ironed.[8]

A number of White people remembered them there. One rancher, T.S. Garrett, whose wife Mary was an avid horsewoman, liked to tell the story of her outracing all challengers on her splendid buckskin horse and a delighted Matt Campfield winning all the bets: “Another plug of Climax [tobacco] on Mrs. Garrett!” Campfield would yell at the start of each race.[9]

When the Fremont Elkhorn and Missouri Valley Railroad came out of Nebraska and up the North Platte River valley late in the 1880s, the Campfields must have realized that Rock Creek’s days as a shipping hub were numbered. In 1888, the railroad reached what’s now Casper, and the town began. Matt and Fannie Campfield moved again.

Life in early Casper

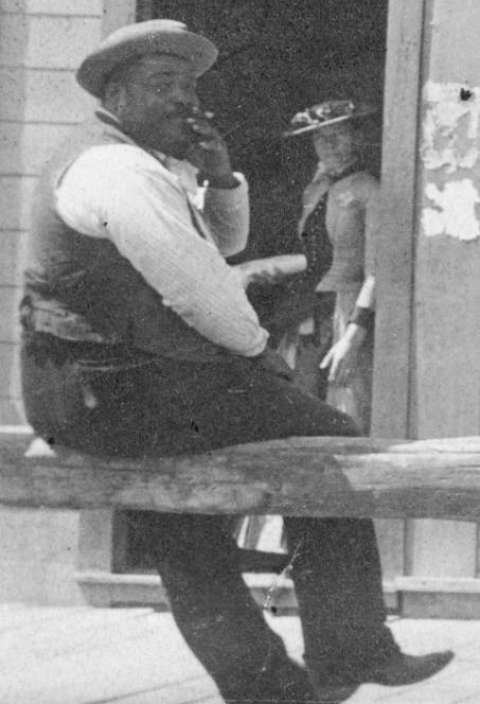

W.S. Kimball was publishing a newspaper in Glenrock, 20 miles east of Casper and the next-to-last town on the F.E.&M.V.R.R. One day a spring wagon, piled high with pots, pans, chairs and bedsprings—and with a coop full of live chickens hanging off the back—came rolling and clucking down the street. Up on the wagon seat were a “large and portly” man and a “somewhat tall and angular woman,” Kimball remembered. He called them Uncle Matt and Aunt Fannie Campfield, as people in Casper would come to know them, using the terms that conveyed a patronizing respect toward Blacks who were well liked and not young.

Kimball wrote a long letter to the Casper Tribune-Herald in 1936, a few days after the paper had settled the leg-bone mystery to its satisfaction. Kimball supported the paper’s conclusions. Matt had clearly lost his feet long before he came to Casper.

That first time he saw the Campfields, Kimball wrote, they were en route from Rock Creek to Casper, behind two bony horses that “could just about pull the load.”

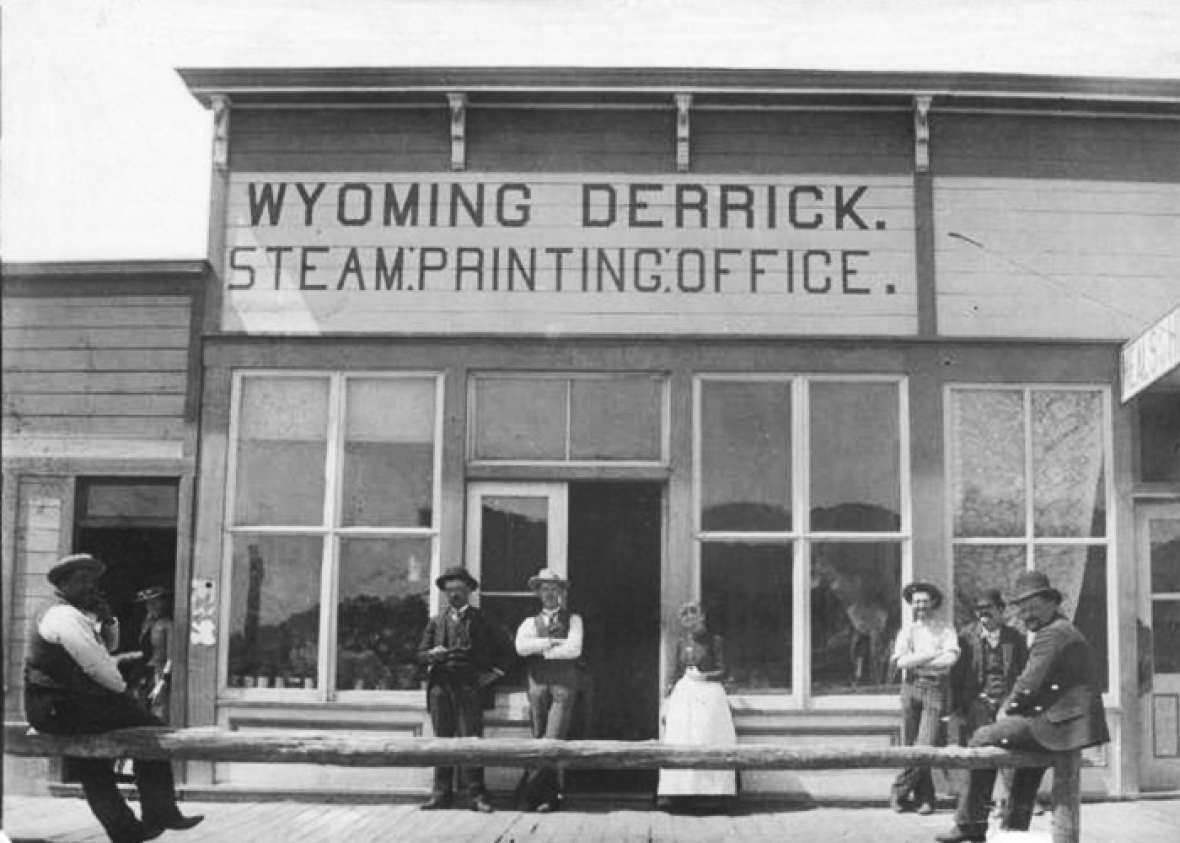

Kimball himself moved to Casper in the spring of 1890 to start “a red-hot Democratic newspaper,” the Wyoming Derrick. The Derrick office and print shop was just north of Campfield’s barber shop, on the west side of Center Street, between what are now Midwest Avenue and Second Street—the block where the Rib & Chop House is now. Two years later Kimball bought a half interest in a drugstore just south of the barbershop. He saw Campfield every day and came to know him well.

Natrona County coroner

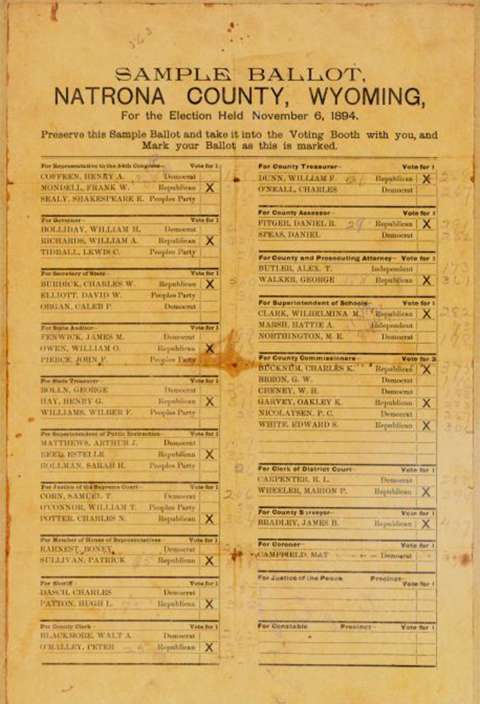

Campfield had “a keen and alert mind” and was “beloved and respected by the people,” Kimball remembered. The people of Natrona County thought well enough of him to elect him twice as Natrona County coroner on the Democratic ticket, in 1892 and 1894. People in those days, Kimball recalled in the letter, were less worried about “race, color, or creed” than they became later. “[E]arly settlers were keen judges of character, honoring courage and integrity [and] quick to detect a ‘streak of yellow’”—that is, cowardice.

A missing bathtub and an eviction

One story that lasted in Casper’s Black community shows the kind of courage the Campfields needed to survive. In the back of his shop Matt had a bathtub where a dusty sheepherder, say, could get a bath after his haircut. Baths cost 50 cents.

A cowboy named George Mitchell stole the bathtub and took it out to Alcova, 30 miles from town, and set it in hot springs near the edge of the North Platte River. Instead of going to the police, or going directly after the cowboy, Campfield used a quieter tactic. Every time a customer came to the shop looking for a bath after that, he made a mark on the wall. These marks would have become well known around town. Casper only had about 500 people in the early 1890s.

Mitchell later returned the tub and started a lumber business. By then there were 70 marks on the barbershop wall. When Campfield needed lumber—perhaps for a cabin or sheds on his homestead claim, west of town—he went to Mitchell’s lumberyard, and demanded and got $35 worth of lumber in exchange for the business Mitchell had stolen from him by stealing the tub.[10]

In 1894, Kimball acquired full interest in the drugstore. With that came title to the building where Matt had his barbershop. Business must have been good, as Kimball decided to expand the drugstore into the barbershop space between his two properties. Campfield had to move. He wasn’t pleased about it.

The day Campfield moved, Kimball remembered years later, there was a gunfight on Center Street between the mayor and another man. One bullet went through the other man’s heart, and two more came through the front of the drugstore and hit the wall right behind where Matt would have been cutting hair. Kimball claimed he’d saved Matt’s life by evicting him. He doesn’t say if Matt agreed with that conclusion.[11]

A veteran’s pension

Maybe because he couldn’t get around much, Campfield was a big man and his health was not good. In 1891, he applied for an invalid’s pension due him as a veteran of the Union Army. Friends filed affidavits saying they knew him well and admired him, and that he could do only about half the work of an able-bodied barber. His doctor noted that both Matt’s stumps were often sore and tender, and the right one still bled from time to time.

Campfield also had rheumatism and heart trouble. He couldn’t lie on his back at night because to do so gave him “a smothering sensation;” his heart sometimes beat irregularly and he was often short of breath. He was 5 feet 9 inches tall and weighed 250 pounds. The doctor could not clearly hear the sound of Matt’s heart “on account of adipose tissue”—that is, fat.[12]

The pension case was straightforward. Campfield had served in the Army, and he was partly disabled. He was granted a pension of $12 per month beginning in September 1892.[13]

Then on the evening of March 5, 1897, while he and Fannie were getting ready for bed, Matt dropped dead on the floor of their room. He was about 52 years old.[14]

A widow’s pension

Fannie was devastated. She also suffered from rheumatism and was not in good health. With the help of friends in Casper and the same lawyer in Washington, D.C., who had worked on her husband’s case, she applied a few weeks later for a pension as a widow of a Civil War Union soldier. The pension, if she could get it, would bring her $8 per month.[15]

Over the next six months, she sold most of their property to pay Matt’s $1,200 in debts. This included 500 sheep that Matt had bought on an installment plan, three horses, some sheds on the homestead claim, a mile of wire fence and a wagon.[16] She returned to Leavenworth in December of that same year, and spent the rest of her life trying to get the government to pay the pension she was certain she deserved.

Over the next six months, she sold most of their property to pay Matt’s $1,200 in debts. This included 500 sheep that Matt had bought on an installment plan, three horses, some sheds on the homestead claim, a mile of wire fence and a wagon.[16] She returned to Leavenworth in December of that same year, and spent the rest of her life trying to get the government to pay the pension she was certain she deserved.

Her friends and family members in Casper and in Kansas filed many affidavits to the effect that she was of good character, that she had been married only once and that Matt, likewise, had never been married to anyone but her. After she’d been back in Kansas two years, she visited a Dr. A.G. Abdelal for her rheumatism. When he learned she was getting nowhere with her pension application, he offered to help. As a doctor, he said, he could make things move along faster. He started collecting small fees from her to do this work and gradually larger ones. Eventually he borrowed money from her as well. Then he left Leavenworth and went to California.[17]

In June 1901, a clerk in the Pension Bureau in Washington noticed some discrepancies in Fannie’s application file.[18] A certificate transcribed from public records in Kansas showed she and Matt were married in 1874. But an affidavit from Fannie in Casper placed the marriage in 1877.[19] Further, some documents showed she was Fannie Davis before she was married; others showed her as Fannie Crump. The different names, she explained later, were due to the fact that she’d been sold away from her family at the age of 8, and had taken the last name of the new owner—Davis—while other family members had taken the name of an earlier owner, Crump. Some people in Leavenworth called her Fannie Crump as a result. The Washington office referred the case back to a pension examiner in Kansas.

Pension examiner Elias Shafer interviewed Fannie at great length about her life. He also interviewed James and Ellen Crump—Fannie’s brother and sister—her brother-in-law John Brown, Samuel Hagwood, who had known Matt in the Army, a neighbor or two, and one or two White women Fannie had worked for.[20] Shafer came away from these interviews sympathizing with her because of her victimization by Dr. Abdelal, convinced she was honest and convinced she badly needed the money. But he felt there were still more people to talk to about her. Washington ordered him back to work on the case.[21]

Only at this point does Shafer seem to have checked back through public marriage records in Leavenworth. The records showed a Mathew Campfield had married a Paulina Davis in November 1867.[22] Finally Shafer found a Mary Marsh, also called Paulina Marsh, who said she was the woman who had married Campfield not long after he was discharged from the Army and before he lost his feet.

“They tell me Mary and Paulina are about the same. Some call me one name and some another,” the woman told Shafer. Her life story wandered unconvincingly through the decades, across the West, and among various husbands. She appears to have been a prostitute some of the time, both in Leavenworth and later in Cheyenne. Still, the records were pretty clear that she had married Matt Campfield, and though they may have spent only three or four scattered weeks together in their lives, neither had ever filed for a divorce.[23] This meant that Fannie was not Mathew’s legal widow, and therefore was not entitled to the pension.

Her application was rejected formally on May 24, 1902.[24] Apparently, however, no one in Washington bothered to inform her. In 1916, a lawyer in Lawrence, Kan., wrote the pension bureau to find out if there was any record of her case.[25] There was, the bureau answered, and gave the 1902 date of the rejection of the application.[26] A letter to Washington followed from a D.B. Hunnicutt of the local chapter of the G.A.R.—the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veterans’ organization. Fannie Campfield, he said, “is a hard working, honorable Christian woman aged and crippled with Rheumatism a true and worthy soldiers widow” whose plight would soon be turned over to Fannie’s senator and congressman.[27] More letters followed from the congressman as late as 1918. Answers, if there were any, have not survived.

A new gravestone

Mathew Campfield was buried in the Highland Cemetery in Casper. By 1936, memories of him and of the nature of his disability were getting a little hazy, at least among Casper’s White people. Fortunately W.S. Kimball wrote his long letter to the newspaper that year. Accounts since then have relied primarily on Kimball’s letter.

Near the end of the account, Kimball noted that Matt’s wooden grave marker was weathering badly and urged the Natrona County Pioneer Association to replace it with a marble stone. But it took Casper’s Black community to bring that about.

In the fall of 1954, when she was running for the first time for the Wyoming Legislature, W.S. Kimball’s daughter, Edness Kimball Wilkins, was invited by the Rev. Belton Randall to speak to the congregation of the Grace African Methodist Episcopal Church in Casper. Wilkins spoke about Matt Campfield that Sunday night. Afterwards, the Casper Morning Star reported, the congregation launched a fund drive for a new gravestone.

In the fall of 1958, Rev. Randall roped several other black churches in Casper into the effort. The newspaper ran a photo of the preacher in the cemetery, kneeling by Matt’s wooden grave marker, looking up at Wilkins, who is looking down at him. In front of the marker, a metal stake with a star on it shows Campfield a member of the G.A.R. By the spring of 1960, the Harmony Art and Literary Club had raised enough money at last to replace the wooden marker with a gravestone. It’s still there, among the stones of Casper’s earliest citizens, and looks as if it will be there a long time yet.[28]

Resources

Primary sources

- Garrett, T.S. “In Memory.” Annals of Wyoming 4, no.1 (July, 1925): 264-65. The account is repeated in Burroughs, Guardian of the Grasslands, cited below.

The following items are cited more fully in the footnotes:

Newspapers

- Casper Morning Star

- Casper Tribune-Herald

- Casper Tribune-Herald & Star

- Casper Tribune-Star May 29, 1960

- Casper Journal, March 22, 2001

- Natrona Tribune

Archives

- Fannie Campfield Pension Records, National Archives

- Mathew Campfield Military Records, National Archives

Secondary sources

- Burroughs, John Rolfe. Guardian of the Grasslands: The First Hundred Years of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Pioneer Printing and Stationery, 1971, 316.

- “A Brief Outline of the Negro in Wyoming.” Booklet published 1955 by the Grace Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Casper. Titled and transcribed by local historian Bob David into a personal notebook, Casper College Western History Center archives, David notebooks pp. 4338-4339, February 1956.

A note on sources

In the footnotes, C T-H stands for Casper Tribune Herald. FCPF stands for Fannie Campfield’s Pension File.

Other Casper newspapers are cited throughout the article. One mention of Campfield not included in this narrative was in Vol. 1, No. 1 of the Natrona Tribune, which published its first edition in 1891 and was a serious competitor to Kimball’s Derrick. The edition included introductions to a number of Casper’s businessmen, surely hoping that buttering them up would lead them to advertise in the paper in the future. Campfield’s notice ran as follows:

“MATT CAMPFIELD, tonsorial artist. Matt is an old timer in this country, he having been here for over thirteen years. He put up the fourth building in Buffalo, Wyoming and was an early settler in several towns through this country. He has a neat shop with bath rooms in connection. Matt came to Wyoming directly from Africa in 1867.”[29] This last detail was not true, of course, but perhaps a way for the paper to let its readers know that Campfield was African-American.

Archival sources for the article include Mathew Campfield’s Civil War-era military records at the National Archives, and Fannie Campfield’s pension file, also at the National Archives. Civil War military records are generally quite brief, showing the dates and places of the soldier’s enlistment and mustering out, his rank and promotion dates, and not much else. The Civil War Pension files, however, are often packed with personal information, as the Pension Bureau had to make sure claims were honest. Thus the bureau often demanded lengthy statements testifying to the claimant’s character and to medical and financial conditions. Records of Mathew Campfield’s original pension claim are included in Fannie Campfield’s pension file. I’m grateful to former archivist Kevin Anderson at the Casper College Western History Center, and especially to Ami Dyrek, formerly of the Casper College Library, who rounded up the Campfield military and pension records years ago and was kind enough to share them with me.

For more on Civil War Records in the National Archives, see http://www.archives.gov/research/military/civil-war/index.html, and for Civil War pension files, see http://www.archives.gov/research/military/index.html. See also tips for researching African-Americans in National Archives resources at National Archives documents having to do with African-Americans in the Civil War at http://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/.

And for a lesson plan using original documents on black soldiers in the Civil War, see http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war/. All links accessed Jan. 21, 2016.

Field Trips

The original wooden marker for Matt Campfield’s grave is in the collection of the Fort Caspar Museum and may be seen there on request. Campfield’s grave with its new stone is easy to find in Block 8, on the right just inside the front gate from Conwell Street into the Highland Cemetery in Casper. More information on the cemetery is included below.

Illustrations

- The photo of the band of the 107th USCI is from the Library of Congress. Used with thanks.

- The two photos of Mathew Campfield, the image of the 1894 ballot and the 1958 photo of his grave are from the Frances Seely Webb collection at the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The 1974 photo of Rock Creek, Wyo., is from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.

- The rest of the photos are by Tom Rea.

[1] “Leg Bones of Skeleton Exhumed at Old Fort Site Recalls [sic] Pioneer Tragedy,” Casper Tribune-Herald, hereafter C T-H, March 22, 1936, MS 334B; “Leg Bones Declared Those of Man Who Constructed Bridge Near Fort Caspar,” C T-H March 24, 1936, MS 336B.

[2] Mathew Campfield military records, National Archives.

[3] Fanny Campfield Pension File, National Archives, hereafter FCPF, M. Campfield affidavit, Jan. 18, 1892; Hagwood affidavit, Jan. 10, 1902.

[4] FCPF, Woodhull affidavit, 27 May 1892

[5] FCPF, James P. Smith, George W. Harmony affidavits, March 19, 1891.

[6] FCPF. F. Campfield affidavit, Dec. 24, 1901.

[7] Wyoming Blue Book, (Cheyenne: Wyoming State Archives, 1974), vol. 1, p. 236.

[8] FCPF. F. Campfield affidavit, Dec. 24, 1901. The town of Rock Creek was abandoned after the Union Pacific re-routed its main line in 1901. The earlier town was north of the present town of Rock River.

[9] T.S. Garrett. “In Memory,” Annals of Wyoming 4:1, (July, 1925), pp. 264-65. The account is repeated in John Rolfe Burroughs, Guardian of the Grasslands: The First Hundred Years of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, (Cheyenne: Pioneer Printing and Stationery, 1971), p. 316.

[10] The story comes from a booklet printed in 1955 by the Grace Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Casper, titled “A Brief Outline of the Negro in Wyoming,” and transcribed by local historian Bob David into a personal notebook, Casper College Western History Center archives, David notebooks pp. 4338-4339, February 1956.

[11] “Matthew Campfield, Pioneer,” Casper Tribune-Herald, March 29, 1936, MS 339B.

[12] FCPF Smith, Harmony affidavits March 19, 1891; Dr. Miller affidavit June 5, 1891; Dr. Leeper affidavit April 21, 1897.

[13] FCPF, U.S. Pension Bureau to J. Thomas Turner, atty., Sept. 5, 1892.

[14] Mathew Campfield’s military records, which show his age as 18 when he enlisted in 1863. Other documents are not consistent on the subject. Many slaves’ birthdays were never recorded.

[15] FCPF, Application for Widow’s Pension, March 26, 1897.

[16] FCPF, Wheeler, Bull affidavits, September 10, 1897.

[17] FCPF, J.M. Spencer affidavit Sept. 18, 1901; F. Campfield affidavit Dec. 24, 1901.

[18] FCPF, note from C.A. Meyers, U.S. Bureau of Pensions, June 6, 1901.

[19] FCPF, Farrell affidavit Sept. 10, 1897; F. Campfield affidavit Aug. 10, 1899.

[20] FCPF affidavits from F. Campfield Dec. 24, 1901; Edrich Thomas Dec. 26, 1901; James Crump Dec. 30, 1901; Ellen Crump and Samuel Hagwood Jan. 10, 1902; John Brown, Emma Wilhelmi, and Belle Spurlock, Jan. 11, 1902.

[21] FCPF, Shafer to commissioner of pensions, Jan. 13, 1902; commissioner of pensions to Shafer Jan. 29, 1902.

[22] FCPF, Leavenworth County marriage license transcription Nov. 18, 1867, copy certified May 8, 1902.

[23] FCPF, Mary/Paulina Marsh affidavit, May 8, 1902.

[24] FCPF, M. Thomas and C.A. Meyers, reviewers, U.S. Bureau of Pensions, May 23 and 24, 1902.

[25] FCPF, S.D. Bishop to commissioner of pensions, March 17, 1916.

[26] FCPF, G.M. Saltzburger, commissioner, Civil War Division, U.S. Bureau of Pensions, to Fannie Campfield c/o S.D. Bishop, April 11, 1916.

[27] FCPF, D.B. Hunnicutt to G.M. Salzguber [sic], commissioner, U.S. Bureau of Pensions, May 8, 1916

[28] Casper Morning Star, Nov. 2, 1954; Casper Tribune-Herald & Star, Oct. 5, 1958; Casper Tribune-Star May 29, 1960; “North Casper park to be named for Campfield,” Casper Journal, March 22, 2001.

[29] Natrona Tribune 1:1, June 17, 1891, p.2 col. 2.