- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Locating The Past: Marking The Site of The Wago...

Locating the Past: Marking the Site of the Wagon Box Fight

One summer morning in 1908, Samuel S. Gibson rode horseback along Little Piney Creek south of present Story, Wyoming, near Sheridan County’s southern border. Gibson’s companion, Charles E. Bezold, rode alongside, eager to hear the older man’s stories of fighting Red Cloud’s warriors more than 40 years before.

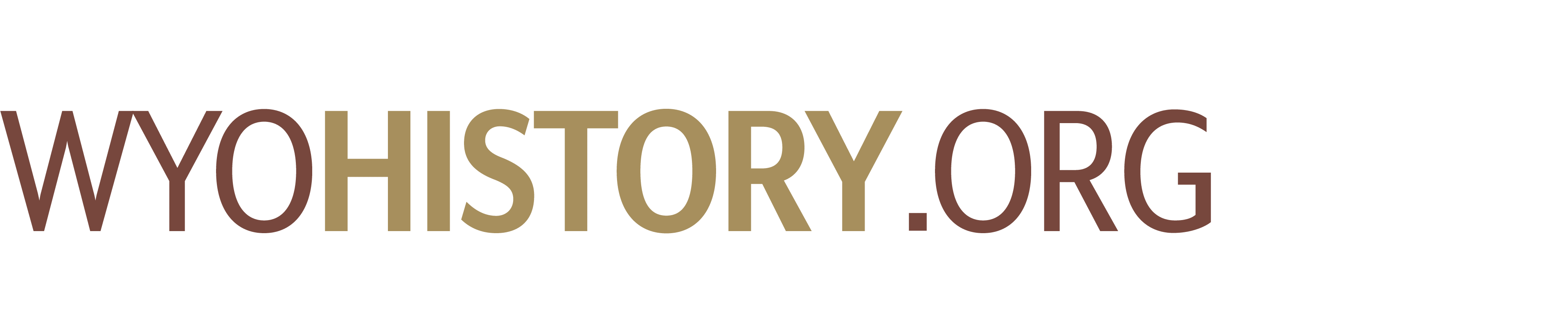

They knew they were near the site of the Wagon Box Fight, a battle in August 1867 between hundreds of Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors and 32 U.S. troops and civilian woodcutters. The white men, a woodcutting detail from nearby Fort Phil Kearny, had made a small stock corral from wagon boxes lifted off the running gears. When they were attacked, the corral became their perimeter of defense. They were armed with new Springfield breech-loading rifles—much deadlier firepower than the tribes had encountered up to that point—and kept their attackers at bay all day.

The outcome was dramatically different from a nearby fight nine months earlier: Riding out in snow and bitter cold from the same fort, Capt. William Fetterman and all 80 men in his command were ambushed and killed by warriors. The fights were two of the main conflicts in Red Cloud’s War which briefly succeeded in driving the Army out of that country. These battles were named for the Oglala Lakota war leader.

Gibson was only 18 when he fought in the Wagon Box Fight, but recalled it vividly. When the men came to a fence blocking them from riding any further, Gibson pointed to the spot where he remembered the wagon-box corral having been located. Several days later, Bezold returned to find handfuls of shells and other artifacts there, including a crushed canteen.

The two men probably met by chance during the large celebrations on July 3 an 4 in nearby Sheridan that year to celebrate a new monument at the site of the Fetterman Fight. The Sheridan Commercial Club invited Chief Red Cloud to the ceremonies, and also Gen. Henry B. Carrington, commander at Fort Phil Kearney at the time of the battles. The ceremonies included a reenactment staged by U.S. regular troops and Crow performers. Too elderly to leave his home on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Red Cloud did not attend the festivities. News of Carrington’s visit brought in a large crowd, however, including several men who had served under him—like Sam Gibson, who had traveled from eastern Nebraska. The event would ultimately inspire Gibson and others to push for a similar monument and celebration to honor the men who fought in the Wagon Box Fight.

For several years Wyoming’s U.S. Rep. Frank Mondell, who’d managed to find federal funds for the Fetterman monument, attempted to secure an additional $3,000 to mark the Wagon Box Fight. Likewise inspired by the overwhelming interest that summer, Gibson wrote his account of the battle with hopes of publishing it. Both men found little success.

Image

Image

Dueling theories about the spot

In 1915, the history-minded Grace Raymond Hebard, longtime University of Wyoming professor of political economy and other subjects, accepted an unpaid appointment as secretary to the Wyoming Oregon Trail Memorial Commission. Expanding the work to include sites along the Bozeman Trail as well, Hebard reached out to a former student, Vie Willits Garber, of Big Horn, Wyoming, in Sheridan County. Her 1911 University of Wyoming master’s thesis was on plant life along the Bozeman Trail. In her thesis correspondence with Hebard, she vividly described tracing the trail on horseback while working to sift the truth out of old-timers’ tall tales. Hebard enlisted Vie and her husband Alvin LeRoy “Roy” Garber to help find the true location of the Wagon Box Fight. The site at the time remained unmarked. Despite Gibson’s and Bezold’s 1908 investigations, local lore only pointed to some supposed rifle pits in the area.

Hebard visited the site in August 1915. She walked the area with the Garbers and two other landowners. By now there was disagreement between backers of a site in Sheridan County and one in Johnson County; still others supported a spot on the county line. With little evidence, Hebard preferred the Sheridan County site, but also thought that if the spot on the county line was chosen, it “might be well, for a great rivalry exits between these two counties, and placing the monument in Sheridan County might not measure much for co-operation.” Hebard went home to Laramie to continue her investigations, enlisting Vie and Roy Garber in her efforts.

Image

She began with published historians Cyrus Brady and E.A. Brininstool. Both men directed her to Samuel Gibson. By September, Hebard had already ruled out the rifle pits as not matching any of the published depictions of the battle. She began corresponding with Gibson.

By now Gibson felt bitter about historians who had used his experiences to publish their own work. He was suspicious of Hebard and frustrated with Wyoming’s “Aristocratic Congressman” Mondell’s failure to come up with funds for a Wagon Box monument.

His pride mixing with his need, Gibson tried to bargain with Hebard for payment for his experience and expertise. She explained that her official resources were limited, but offered to pay Gibson from her own purse and mentioned to him her patriotic motivations to preserve the site. This thawed him out. A flowery correspondence followed, with Gibson often referring to Hebard as his “charming friend.” More than 400 pages of their correspondence is preserved at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center in Laramie.

By January 1916, Hebard was corresponding with another survivor, Max Littmann, who agreed to plan a trip to Wyoming from St. Louis, Missouri to visit the site and Hebard. That winter Vie Garber wrote to Hebard about all of the old-timers and their theories. Yet, one story of a man named Bezold seemed promising to Vie and she was determined to meet the man.

Referring to Littman’s planned visit, Vie wrote Hebard January 14, “I just feel sure that if he were taken over there and not influenced by anyone that he could tell us just what we wish to know. As for Gibson—he surely is a man of many words, but I will not pass my opinion until Ive talked with Mr. Bezoldt. [sic]”

The Custer anniversary

The summer of 1916 drew 5,000 people to the area to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Custer’s Last Stand, as people called it then—the Seventh Cavalry’s disastrous defeat on the Little Bighorn in Montana.

One of the attendees, Chicago historian Walter Mason Camp, had spent years tracking down both White and Native survivors of the Custer fight. By now, Camp’s interests had expanded; in 1915, he also interviewed Max Littmann and Samuel Gibson. After the ceremonies in Montana, Camp traveled through the Bighorns to visit other battlefields and sacred sites like the Medicine Wheel. He was joined by members of the Sheridan Commercial Club and Herbert H. Thompson, one of the editors of The Teepee Book, a local history magazine. Primarily interested in pre-history, Thompson nevertheless felt duty bound to publish on the Indian Wars; he also had a driving desire to help mark its battles.

Thompson claimed later that when the party reached the area of the Wagon Box Fight, they had “no intent in the world of locating anything.” Still, Camp had statements from both Littman and Gibson with him and a discussion of the exact location ensued. The men searched the area, reading over the survivors’ accounts until they felt they had the correct spot.

A few days later, Camp, Thompson and some others went back and drove a metal pipe into the ground with a brass plate naming the spot. Thompson explained to Hebard that they placed it “more for the purpose of selecting some tangible point to work from than for any other reason . . . this monument will be moved to the exact location whenever that exact location can be determined.” The site was in Johnson County.

Image

Littmann’s visit

Littman, meanwhile, had planned his visit for mid-August. By then he, Thompson and Hebard were all corresponding with each other. Vie Garber also had some conversations with Thompson, in which he took a different tone than he had in his letters to Hebard. “Mr. T. had already praised Mr. Camp to the skys,” Vie reported to Hebard, “…and said that you were selfish & personal in historic matters at which he got a good lecture from me & backed down…”

When Littmann visited on August 15, Thompson drove Littmann, his family, Camp, and another landowner up to the general area—without inviting Vie along.

The party first drove to Fort Phil Kearny, where Littmann requested, “Now do not say anything to me from now on. Let me try to get my bearings and locate the site of the fight of August 2, 1867, without any hindrances.” They rode along the Little Piney until Littmann stopped the car in the lower field in Johnson County.

While Littmann looked at each of the mountains and walked about the area, the rest of the party drifted over to the pipe marker. Littmann’s daughter, Sophia, hid the marker with her long skirt, while her father crawled on his belly and tried to remember his view during the fight, muttering to himself about the mountains. Finally, he walked toward his daughter and the rest of the party declaring, “Gentlemen, this is as near the exact spot as I can locate it.” But during that same visit, Thompson did not drive the party to the Bezold site.

Image

Hebard, in later letters to Vie Garber, did not approve of Thompson and Camp’s methods. “The mere thought that his daughter and the others, went over where the marker was, before he went into that region, perhaps had a psychological effect upon him, was the strong point in my mind, although I did not present it to Mr. Thompson as I did not want to antagonize him in any way.”

Hebard’s return scouting trip

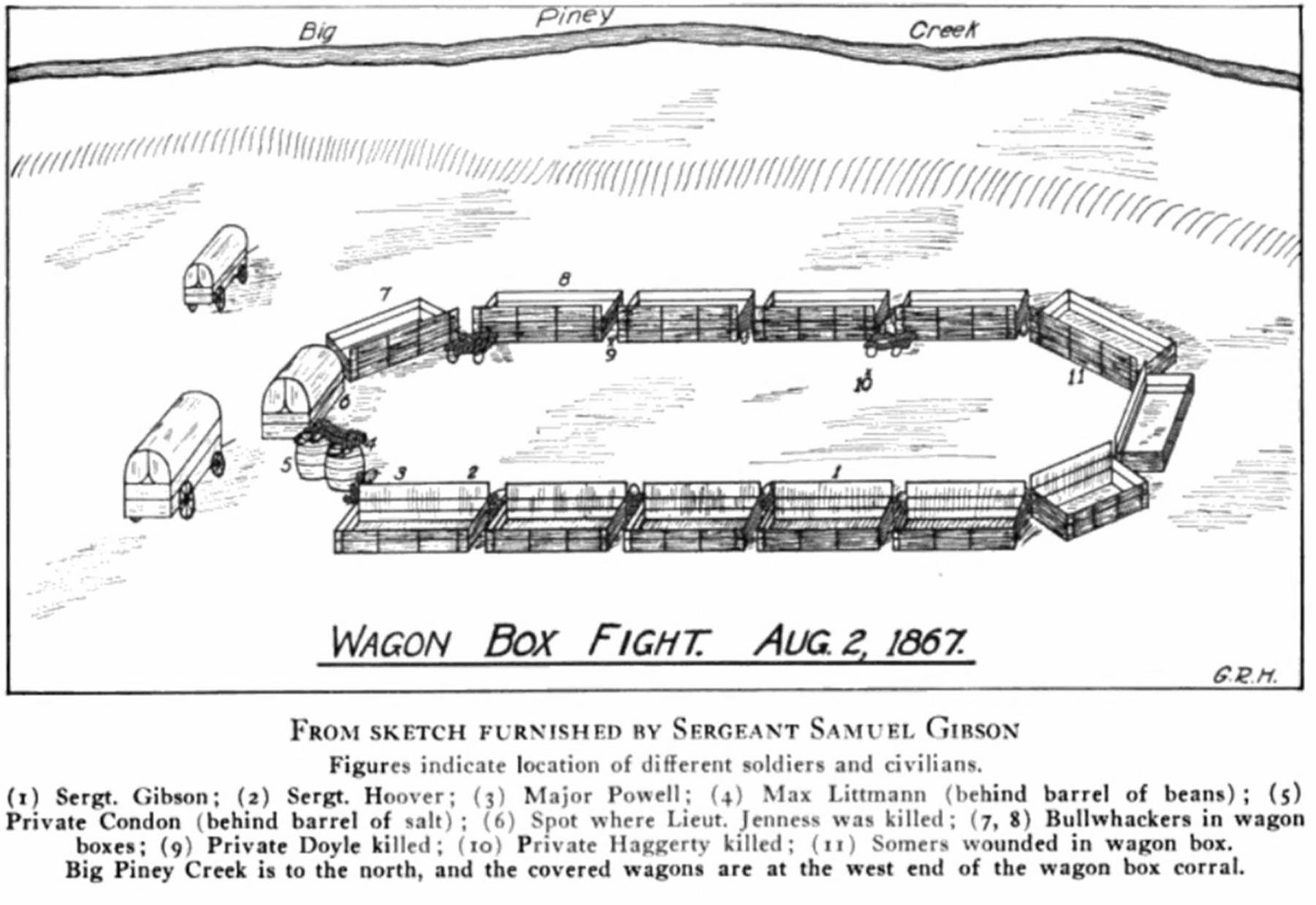

Hebard returned to northern Wyoming in October 1916 to give speeches and preside as state regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution during their annual meeting. And she visited the two disputed Wagon Box sites.

On a crisp, clear October Sunday, Vie and Roy rented a car, bringing along their toddler Orr to take Hebard to meet Bezold. The party first went to the site Bezold had visited in 1908. They spent, Hebard wrote later, “a good deal of the time going on our hands and knees and many times I was prostrate on my stomach… I was thankful that the only kodak of the party was securely strapped on my back, and that no one could take photographs of our to say the least athletic position.” During their crawl, they found a dozen empty cartridges of three different makes, pieces of wooden barrels, wooden wagon tools and “a piece of the wagon box of oak, through which a bolt had been placed.” Several of the shell casings proved to be from centerfire cartridges, the same ammunition for the breech-loading Springfield rifles used by soldiers in the fight.

Afterward, the party crossed the county line to the pipe marker. Again, on their hands and knees, they “could find nothing whatsoever.” Worried that the differing sites would cause conflict between the survivors, Hebard attempted to keep Gibson’s and Littmann’s quarter mile difference quiet.

Not knowing about the difference in opinion, Gibson teased Hebard, “Now about the exact location of the Site of our Fight. Well, Miss Hebard . . . As Littmann has been out there and has located the exact spot where we fought on August 2d. 1867, I am perfectly satisfied that his Judgement is absolutely correct, and you my charming friend ought to be satisfied also.”

After Hebard shared news of the artifacts she and the others had discovered, Gibson declared delightedly, “Why my dear friend. Mr Bezolt has found the site of our Wagon Box Fight without a doubt…” but Gibson feared that Hebard’s letter didn’t seem as elated as he thought it should be. Now that the site had been established by strong evidence, Gibson expected no trouble enlisting the people of Sheridan to place a monument and hold a celebration in time for the 50-year anniversary in 1917. Hebard was not as certain that news of their discovery would be well met.

Planning a monument and a celebrations

A certain M. Steele of the Sheridan Commercial Club initially met Hebard’s suggestion of a 50th anniversary with enthusiasm. After visiting Thompson, however, Hebard remained skeptical about receiving much support for a celebration. Thompson became agitated by Hebard’s interrogation about Littmann’s visit and her declaration that the site was likely in Sheridan County. At the mention of Gibson Thompson declared, “Oh, that Gibson, he is all cock sure.”

The artifacts, as well, would not convince Thompson. He told Hebard, “None of this is any evidence to prove the location of the battle, for there are piles of shells scattered over Wyoming from one end of the state to the other, and skirmishes were fought along the old Piney road hundreds of times.”

Thompson was so convinced that he and Camp had marked the correct spot that when he published Vie’s paper in the Teepee Book in 1916, he changed her article to read Johnson County instead of Sheridan.

Image

Without the support of the locals in Sheridan, a fifty-year anniversary celebration proved impossible. And with the April 1917 entry of the United States into World War I, war fever sabotaged any planning that might have occurred. The German-American Littmann, who had been born in Berlin, made it clear he wished to visit his hometown again after the war was over. Gibson, who was again serving in the Army at the age of 68, working for the quartermaster in Omaha, couldn’t attend because he was overwhelmed by the war effort.

Gibson’s friendly relationship with Littmann dissolved over their difference of opinion and Littmann’s continued support of Germany. Gibson declared to Hebard that should he attend a celebration for the fight he would refuse to dine with or even be under the same roof as a “hyphenated-American” like Littmann.

Both Gibson and Littman had been on the detail that gathered the mutilated, frozen soldiers’ bodies the day after the Fetterman Fight. Like other survivors of the Wagon Box Fight, they made clear to Hebard their hatred of Native Americans. Gibson wrote that he would not welcome them at any celebration. By July of 1917, Hebard was resigned that the anniversary event would not happen.

Gibson’s return

The war ended in November 1918. In 1919, with some funds from the Oregon Trail Commission and some of her own, Hebard was finally able to bring Gibson back to Wyoming. But subsidizing his trip meant she couldn’t afford to travel to Sheridan to meet him. She suggested to Vie Garber that she and her husband, Roy, with Bezold, “go out there in a quiet way and have Mr. Gibson select the site.” Vie agreed. Gibson drove a small metal tie-spike in the spot, along with an old broomstick. After that, correspondence about a marker began in earnest.

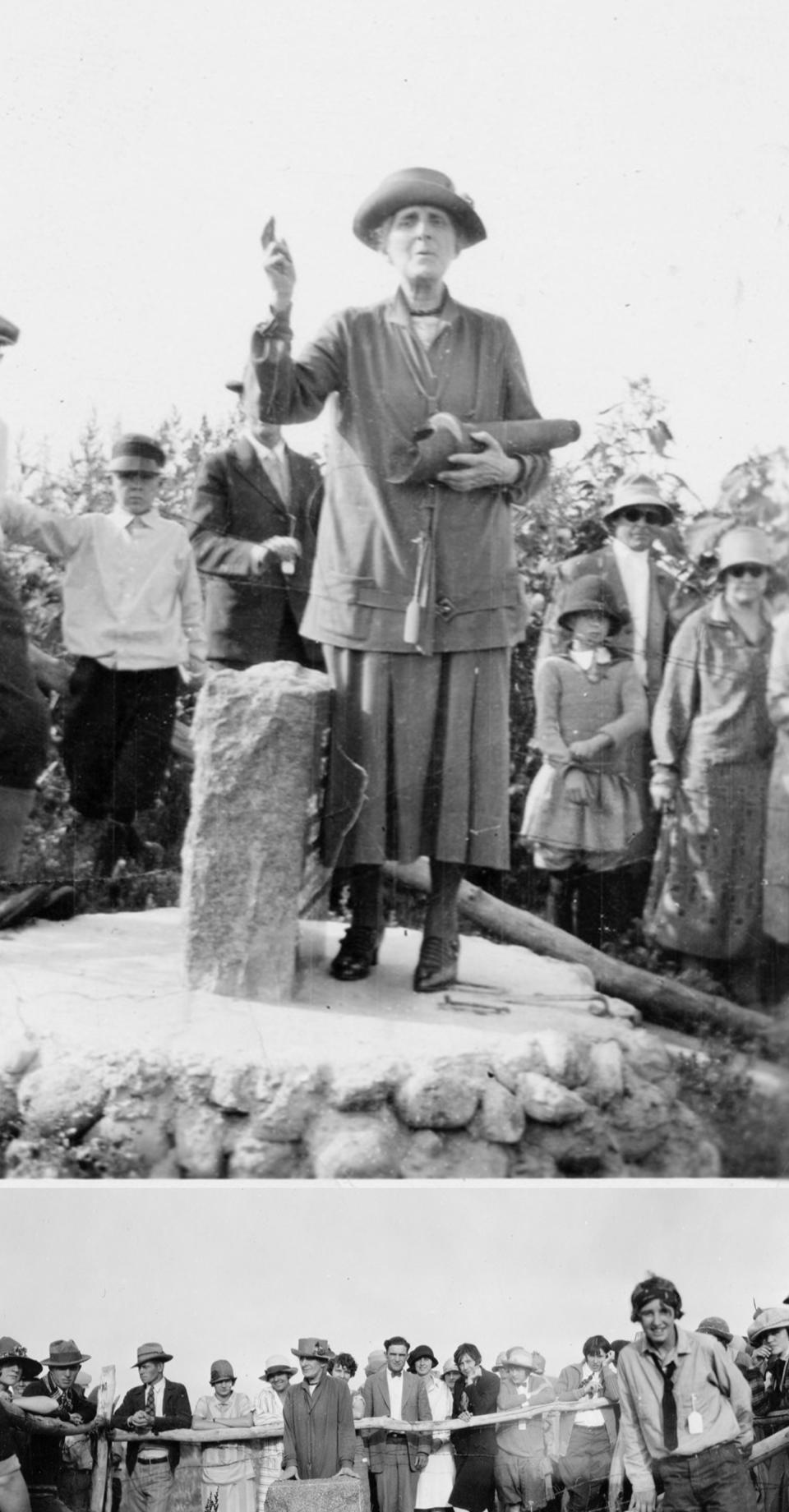

A marker at last

Even with Gibson’s affirmation of the Sheridan County site, Hebard encountered opposition because of the existing pipe marker left by Thompson in 1916. In 1920, Camp and Thompson brought out another survivor, John M. Hoover, who affirmed a site near the pipe. It took Hebard another year but finally in 1921, the Oregon Trail Commission hired Frank Foster with Sheridan Monument Co. to place a small granite monument honoring the battle in the spot Gibson had pointed out to Bezold back in 1908.

Image

Hebard was in her last years when the Army Corps of Engineers began their work to place a large stone monument to the battle, which stands prominently at the location today. In 1929, Corps officers wrote to her about the conflicting markers and asked for information on why she chose the location in Sheridan County.

She sent them a report, remarking that in 1926 she brought a class of 300 out to the site. “Students asked me if I thought they could find anything to indicate that the battle had been fought there, and I said I thought not, because the location had become well-known to souvenir hunters. Even in the face of that, shells were found, and one young man found a piece of [leather] about as big as his middle finger.”

After seven years of investigation, the War Department ultimately agreed with Hebard’s findings, erecting a monument in 1936 in the same location where the state had placed a small granite monument in 1921. The new monument was built by the New Deal-era Civilian Conservation Corps.

While prominent local figures, like historian Jim Gatchell in Buffalo, continued to support the location of the Camp-Thompson marker, in the decades since more archeological studies have substantiated Hebard’s findings. Today, historians overwhelmingly agree the battle took place at the location indicated by Gibson that morning of July 3, 1908.

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund for support that in part made this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Hebard, Grace Raymond Papers. Correspondence, Box 9, Folders 16-18; Box 10, Folders 1-4; Box 30, Folder 23; Box 31, Folders 20-21; Box 36, Folders 15-17; Box 37, Folder 1. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming.

- Camp, Walter Mason Collection. Correspondence, Box 2, Folders 2 and 18. L. Tom Perry Special Collections Repository, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

- Wyoming Digital Newspaper Collection, accessed Aug. 2, 2023:

- The Buffalo Bulletin 21, no. 15, Dec. 21, 1911

- The Laramie Republican 37, no. 10, Aug. 22, 1916

- The Laramie Republican 27, no. 14, Aug. 26, 1916

- The Laramie Republican (Semi-Weekly) 27, no. 95, Aug. 2, 1919

- The Semi-Weekly Enterprise 22, no. 32, July 3, 1908

- The Sheridan Enterprise 13, no. 223, April 26, 1921

- The Sheridan Post 21, no. 34, June 19, 1908

- The Sheridan Post 27, no. 63, Sept. 22, 1914

Secondary Sources

- Cutlip, Kimbra. “In 1868, Two Nations Made a Treaty, the U.S. Broke It and Plains Indian Tribes are Still Seeking Justice.” Smithsonian Magazine, Nov. 7, 2018, accessed Aug. 11, 2023 at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/1868-two-nations-made-treaty-us-broke-it-and-plains-indian-tribes-are-still-seeking-justice-180970741/.

- Drake, Kerry. “The Wagon Box Fight, 1867.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Aug. 2, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/wagon-box-fight-1867.

- Fralick, Lucas. “Frank Mondell: A Congressman for his Times.” March 22, 2023. WyoHistory.org, accessed Aug. 22, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/frank-mondell-congressman-his-times.

- Keenan, Jerry. The Wagon Box Fight, An Episode of Red Cloud’s War. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Publishing Company, 2000.

- Ostlind, Emilene. “Red Cloud’s War.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Aug. 2, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/red-clouds-war.

- Rea, Tom. “Peace, War, Land and a Funeral: The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Aug. 2, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/peace-war-land-and-funeral-fort-laramie-treaty-1868.

- Smith, Shannon. “New Perspectives on the Fetterman Fight.” Nov. 8, 2023. WyoHistory.org, accessed Aug. 2, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/new-perspectives-fetterman-fight.

- Wyoming Heritage. “Fetterman Battlefield.” Nov. 8, 2014. WyoHistory.org, accessed Aug. 2, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/fetterman-battlefield.

Illustrations

- The photos of the landscape around the site of the Wagon Box fight and of the tall rock monument are from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the plaque on the monument is by Vasily Vlasov, rom Panoramio. Used with thanks.

- The rest of the photos and the image of Hebard’s sketch of the battle site are all from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, Used with permission and thanks.