- Home

- Encyclopedia

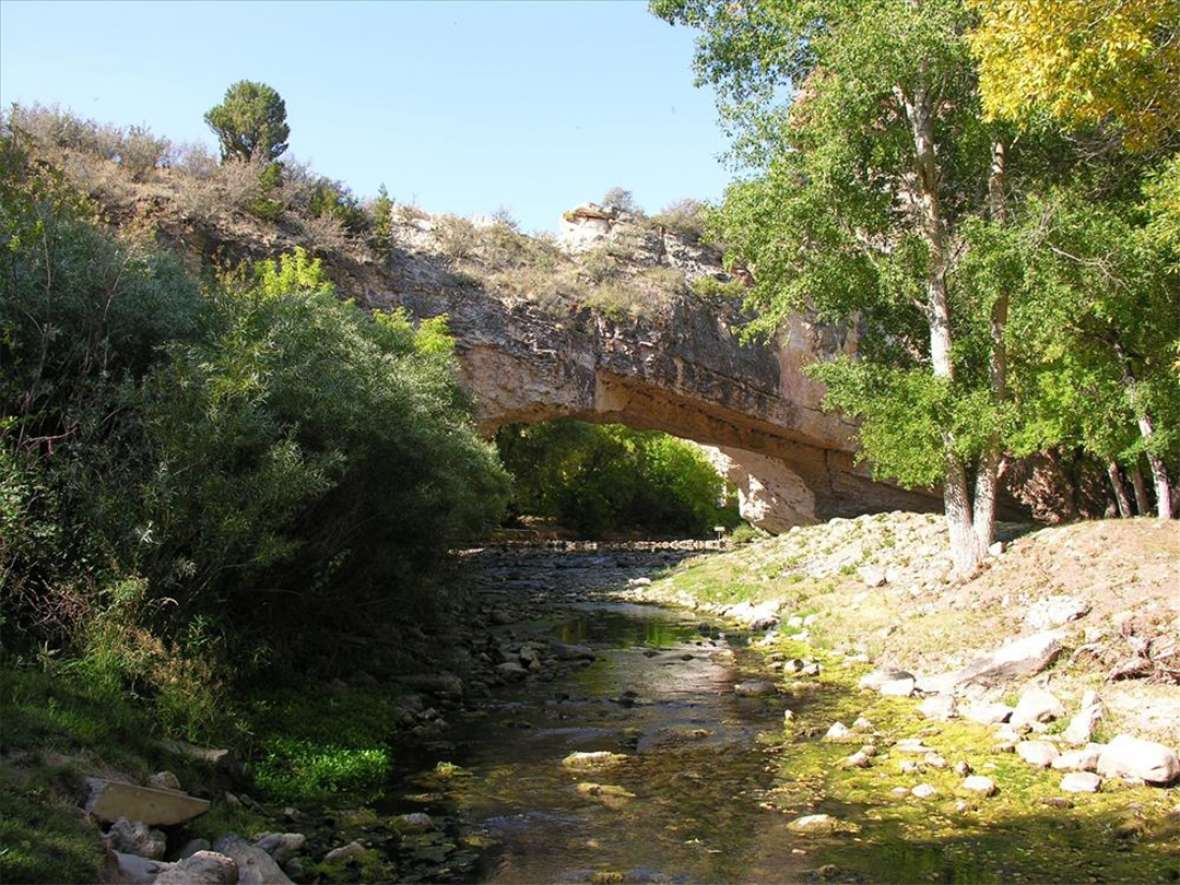

- La Prele Creek Crossing

La Prele Creek Crossing

About 70 miles northwest of Fort Laramie, the Oregon Trail crossed La Prele Creek, flowing north from the Laramie Range toward the North Platte River a few miles away. On a high bluff above the creek mouth the U.S. Army in 1867 would build Fort Fetterman, which became an important supply base in the wars with the Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux in the following decade.

But earlier, in the 1840s and 1850s, the trail left the river for a slightly more direct route, and for the better water available in the tributary creeks. Emigrant traffic was relatively slight through most of the 1840s. In 1849, the first year of the California gold rush, traffic boomed. Fifteen times as many emigrants—25,450 is the best estimate—traveled the trail that year as had the year before.

The creek was named from the French “la prêle,” meaning horsetail, a reference to the genus Equisetum—the odd little stalk with a segmented, bamboo-looking stem and branching head that flourishes on moist, shady creek banks in the Rocky Mountains. Along the creek there are still growths of horsetail and cattails, though it is probably drier now than in trail days. An older name for the same plant is Mike’s Head—which also gave another name to the creek.

The emigrants of 1843 called it Squaw Butte Creek, but by 1846, others referred to it as Beaver Creek. Most diarists did not name the creek at all, however. By the time of the gold rush those who did had settled on La Prele—spelled with great variety and originality. In present Wyoming, the name is usually pronounced with an extra syllable, as though it were spelled “La Parelle.”

“Leaving the Platte out of view,” wrote Pierson Barton Reading on July 20, 1843, during the first year that large wagon companies traveled the trail. “Camped on Squaw Butte Creek about 2 o’clock where we met Messrs. Vasquez and Walker, traders from the mountains, bound for Laramie Fort,” he continued, referring to Louis Vasquez, Jim Bridger’s partner in Fort Bridger, far to the southwest, and longtime fur-trade brigade leader Joe Walker. “Passed on the creek a new made grave over which was a letter informing us it was that of a child killed in Applegate’s company by a wagon passing over its body,” Reading wrote. Here he was referring to the grave of 6-year-old Joel Hembree, who had died just two days earlier and whose gravesite is still the earliest emigrant grave known on the Oregon Trail.

The place was lush and green when diarist Edwin Bryant passed on July 3, 1846. “We encamped this afternoon at one o’clock on Beaver creek, an affluent of the Platte,” he wrote. “The grass and water are good, and the wood is abundant. The timber, which fringes the margin of the stream, is chiefly box-elder and large willows. I noticed scattered among and enlivening the brownish verdure of the grass, many specimens of handsome and brilliantly colored flowers.”

Two years later, the landscape was showing signs of stress from the increasing number of emigrants and their hungry, thirsty livestock “Traveled 18 ½ miles to the A La Prele river,” Hosea Stout wrote July 30, 1848, “where we found some grass but by no means plenty for the immense number of cattle which is now on it. July 31—Lay up. Some cattle strayed for the Platte but were recovered.”

Traveling in early June the following year, William Johnston found the creek crossing a pleasant break from the sagebrush that stretched all directions away from it. “In a few hours we crossed a pretty stream, ‘A la Perle,’” he wrote June 2, 1849, “skirted with fine timber. I noticed a number of wild flowers upon the banks, but away from the stream sterility prevailed, the Artemisia [sagebrush] alone thriving. The road was excellent as any turnpike.”

That year, the first year of the California gold rush, the vast majority of the parties were made up of men traveling without families. At La Prele Creek, the Fourth of July celebration was boisterous.

“Camp on La Parele river,” William Lorton wrote July 3, 1849. “[I]n the night have a grand jubilee fire 2 rounds of Fu de joy [a rifle salute of running fire, from the French “feu de joie”]. 1 grand volley of rifles, revolvers, & musketry. Load an old musket heavy, set a slow match & burst her,” he wrote. “[B]eautiful moonlight night,” he continued, and remembering people at home went on, “think of N.Y. & the preparation there about this time. The La Parele river empties into the Platte & is a right smart stream for a small one …”

Perhaps wary of a Shoshone party nearby, Lorton and his companions were careful to guard their oxen closely. “[D]rove the cattle 2 miles on scant feed, have guard all night. Take their buffalo skins & lie down on the ground to sleep while the relief watches.” But the Indians, he knew, were equally wary of the emigrants’ diseases. “Party of black snake inds camped up in the hills, inds keep away from the road, afraid of the cholera. Cold night …”

Resources

Primary Sources

- Brown, Randy. Oregon-California Trails Association. WyoHistory.org offers special thanks to this historian for providing the diary entries used in this article.

- Bryant, Edwin. What I Saw in California. 1848. Reprint, Palo Alto, Calif.: Lewis Osborne, 1967.

- Johnston, William G. Overland to California. Oakland, Calif.: Biobooks, 1948.

- Lorton, William B. Diary, September 1848–January 1850. C-F 190, Typescript. Hubert Howe Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkley, Calif.

- Reading, Pierson B. “Journal of Pierson B. Reading.” Ed. by Philip B. Bekeart. Quarterly of the Society of California Pioneers 7, no. 3 (September 1930): 134–98.

- Stout, Hosea. On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1848. 2 vols. Ed. by Juanita Brooks. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, 1964.

Secondary Sources

- Unruh, John D. The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1860. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1979, 119-120, 185.

Illustrations

- The photo of the horsetails is from Wikipedia. The photo of La Prele Creek flowing under Ayres Natural Bridge is from the National Park Service. Both are used with thanks.