- Home

- Encyclopedia

- “It Can Be Done:” Mayor Lizabeth Wiley and The KKK

“It Can Be Done:” Mayor Lizabeth Wiley and the KKK

On January 5th, 1923, the Greybull Tribune ran a front-page article praising the Ku Klux Klan. At the farewell services of Reverend W.J. Lloyd, pastor of the Christian Church in Greybull, Wyo., masked men in white robes appeared and ceremoniously delivered a letter and $25 present to the “awe struck minister” before speeding away “in a high powered automobile which awaited them outside.”

The Tribune wouldn’t be the only paper to favorably print the story and letter from the KKK in full. The Greybull Standard described young children exclaiming, “look! there comes Santa Claus” at the sight of the robed men. Reverend Lloyd also published his response, “Although the Klan gave us all no small shock, we have entirely recovered normally and wish to thank you for your kind words of appreciation of our work in Greybull, your splendid cash remembrance, and especially your frank and open elucidation of your principles which I had very much misunderstood, due to current reports.”

A month later, the Klan delivered another donation and similar letter to Rev. William J. Law and the Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church.

Image

The second Ku Klux Klan

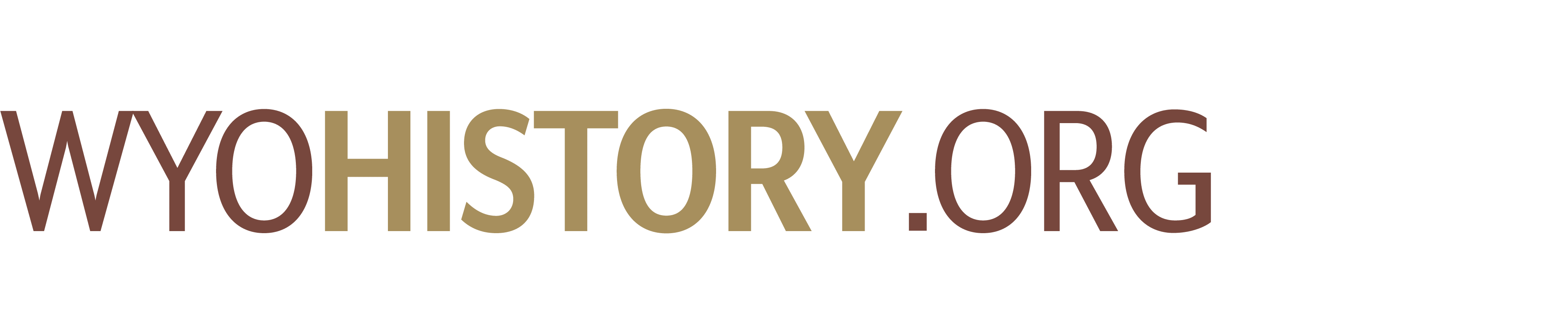

Greybull was not unique. All across the country, the second Ku Klux Klan was growing fast in membership and through public charity, newspaper campaigns and other promotional tactics. J William Joseph Simmons formed the second Klan in 1915 in reaction to the widely distributed racist film Birth of a Nation and the lynching of Jewish factory owner Leo Frank by a mob in Marietta, Georgia. (Frank had been convicted in 1913 of the rape and murder of a 13-year-old girl. Gov. John Slaton, convinced Frank was innocent, later commuted his sentence to life. A mob broke into the prison and hanged him from a tree.) The second Klan was rooted in the white supremacy, terror and pageantry of the first Klan of the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, with added customs and rituals based on Masonic rites.

The hate group struggled to gain membership for five years until it began to flourish in 1920 under the guidance of Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke. By the summer of 1921, the Klan claimed to have grown from a few hundred members to 850,000. Tyler and Clarke accomplished this by specifying white supremacy to be the supremacy of Anglo-Saxon Protestants and thus expanding the Klan’s targets to include Jews, Catholics, and immigrants. They promoted the Klan as a patriotic, Christian organization for “100% Americans,” in a nationwide newspaper campaign and offered free membership to ministers. By 1923, the organization claimed to have membership in the millions.

During the 1920s, there is evidence that the Klan in Wyoming established Klaverns in Casper, Cheyenne, Green River, Greybull, Laramie, Riverton, Rock Springs, Pinedale, Sheridan and more. While the Klan presented itself as a respectful, all-American, Christian organization, its defenders could not hide their bigotry.

After publishing a positive editorial on the Klan in 1922, The Riverton Review printed a critical letter written by O.N. Gibson and invited the Klan to comment. Gibson took issue with the deceitfulness of the Klan, its bigotry, race hatred, and vigilantism.

The Klan responded by masking its members’ bigotry with claims to patriotism and respectability, but another letter from a supporter saw nothing wrong with being explicitly hateful. Signed “A War Veteran,” the man endorsed an antisemitic and anti-Catholic claim that both groups “controlled” the Associated Press. He blamed them for stirring up “most of the excitement over this secret order,” before glorifying the first Klan’s terrorism of Black communities after the Civil War.

Greybull’s opposition to the Klan

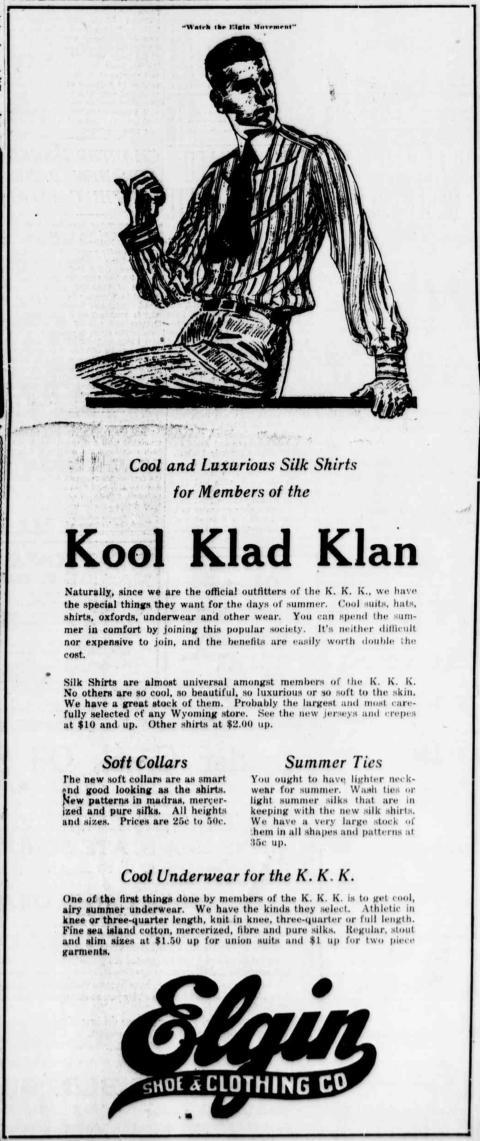

Several citizens of the Equality State vehemently opposed the hate group’s successful spread across Wyoming. In Greybull, a town of 2,140 people in 1920, the fight against the KKK was led by bookstore owner Lizabeth Wiley. Wiley wrote to Grace Raymond Hebard at the University of Wyoming in 1924, “I am intensely anti-klan, but have never talked much of the matter and to the inhabitants in general my idea of it would not have been known, had I not expressed myself very forcibly more than two years ago to a man, who is now a klan leader here.”

Lizabeth Wiley came to Wyoming in 1914 from St. Louis, where, she wrote Hebard, she recalled earning her living “as seamstress, saleswoman, proprietress of rooming and boarding houses, book-keeper, traveling saleswoman, manager of a Baking Powder Factory and running a poultry ranch.” Wiley settled in Greybull with her mother, Mary, and opened a small bookstore using “orange boxes set on end” to create bookshelves. Soon Wiley’s Bookstore also became the home of the Greybull library. Wiley used her bookstore to donate and sell books at cost to the fledgling library, becoming a lifelong advocate for its betterment.

Image

Wiley gained a reputation for being fearless in her convictions and her ability to get things done. While her business activities expanded to include a candy shop with a soda fountain, she also became a more outspoken advocate for community improvement. Over the next ten years, Wiley would negotiate donations to the library and grow its collection to over 3,000 volumes. She served three consecutive terms as the Greybull Women’s Club president, as well as a term as the reporter, and another as the treasurer. At the state level, she served two years as the treasurer of the Wyoming Federation of Women’s Clubs. She also helped to create a city park while serving as chairman of the Civic Committee of the Fortnightly Club.

While Wiley fought to improve her chosen home, the Klan’s presence in Greybull grew. Wiley recalled that leading up to the 1924 election, there were many crosses burned—and a rival organization began burning circles in response. Starting in 1923, the group called Knights of the Flaming Circle (KFC), aimed to fight fire with fire, violently opposing the KKK and offering membership to anyone the KKK would target or deny. For nearly two years, Greybull’s nights were often ablaze with the battling organizations’ burning symbols. With the Klan’s power only growing, and the city’s finances in a state of ruin—Lizabeth Wiley became determined to run for Greybull’s mayor.

A campaign for mayor

She recalled to Hebard, “The activities of the K.K.K. here probably had more to do with my political plunge than did any other one thing. They were hated and feared by the men—feared that they could not be beaten.” Wiley’s decision to run was marked by her characteristic confidence; she wrote, “There has never been a time when I doubted the klan could be beaten and I found that women in general believed as I did.”

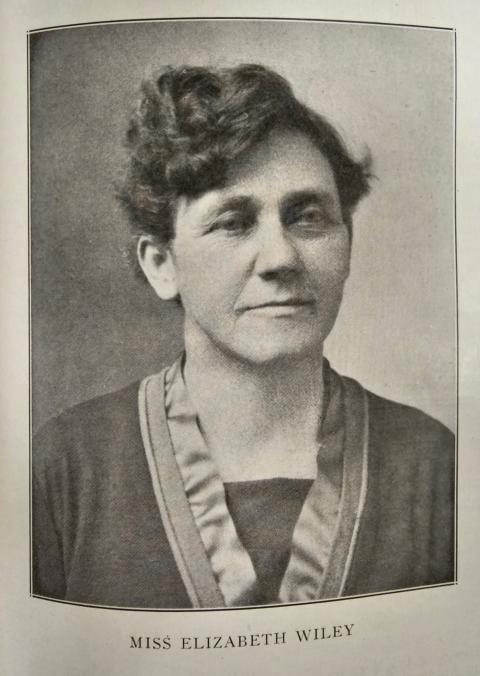

Wiley selected three men for her ticket and wrote three of the four planks of her platform. She explained in an aside to Hebard “(could have elected women, but could not get them to serve).” The first two planks directly addressed the city’s financial woes, promising a “strict economy and efficiency.” The third plank contained a euphemism for the party’s opposition to the Klan, “A business administration with law enforcement by legal methods with equal rights to all and special privileges to none.” [Author’s emphasis.]

Image

The Klan consistently promoted “law enforcement” but it was clear to opponents like Wiley, that the Klan’s idea of law enforcement was driven by bigoted vigilantism and mob mentality. The fourth and final plank promoted “cooperation for the advancement and good of our home town.” Wiley’s confidence reassured voters with her slogan, “It can be done!”

Soon even the men who feared the KKK were convinced by Wiley and believed “it could be done.” Wiley wrote they tried to “ditch me” by replacing her with a male candidate but failed. On May 13th, 1924, Lizabeth Wiley received 444 votes; her opponent W.W. Braden received 278. The incumbent mayor, G.M. Clement received only 1 vote.

To celebrate Wiley’s victory the KFC burned a circle. Wiley quickly responded, publicly thanking the men and women of Greybull for their support at the polls before scolding, “I regret that some of my youthful boosters became over enthusiastic and indulged in illuminated display. Please don’t do it again. I appreciate your boosting and good intentions, but am asking you to help bury the hatchet and hasten an era of a “pull-together town.”

In 1929, the Chillicothe Constitution, a newspaper in Missouri, recounted Wiley’s first public battle with the Klan as mayor:

The Klansmen announced they would attend the first council meeting in a body and masked.

“Lizzie” warned them no masked persons would be allowed inside the room.

“Wear masks and take what falls on you,” she said.

No Klansmen came.

Wiley’s first term was marked by her successful intimidation of the Klan and her competent town management. A year and a half into her two-year term she wrote to Hebard, “The mayor’s job is rather tame this winter—just trying to amend and improve from Ordinances, keep the youngsters out of the Pool Halls, foster the Ice Skating and make plans for spring.” Wiley’s town improvements included improving the city’s water system and reforming the burn laws.

Her past work experiences also inspired her to advocate for statewide child labor laws. Writing to Hebard she explained, “I, of course, realize the importance of this matter, since I was a Working Woman in St. Louis for twenty years and was there at the time that children as young as seven were working---I did not just hear about it; I saw it. I am heartily in favor of regulating child labor---or preventing---so long as there is no sex distinction made.” In 1925, she promised to advocate and organize for the cause at the local and county level.

She also moved the city treasurer’s office out of one of the town banks, which was an election promise that had won her opposition from both banks. She was determined to manage the city’s finances like a business and foster a city government friendly to business owners.

Scandal in the Second Term

In the May 1926 election, Lizabeth Wiley ran unopposed for another two-year term as mayor. From cleaning up trash to investigating bootleggers, Lizabeth Wiley took a hands-on approach to her administration. After shadowing the home of Thelma Olson for two months, Wiley became convinced that Olson was running liquor out of her house. Wiley obtained a warrant from Justice of the Peace Draper and conducted a raid with Police Chief Ed Cusack and Deputy Sheriff Frank James.

The raid on Olson’s home began with Cusack threatening to break down the front door. In Wiley’s public statement she recalled, “The door was locked and the house darkened, giving the impression that no one was home, but the mayor, having shadowed the house was sure that two persons were inside and insisted on entrance being made.”

Finally, entry was obtained, but no liquor was discovered. Instead, the three found Thelma Olson with Sheriff A.C. Burgess. Burgess fired Frank James on the spot and claimed the raid ruined his investigative work with Olson who had been passing him tips on the illegal liquor trade. Olson then sued Lizabeth Wiley and the others for $5,000 in damages.

The scandal received national attention when Lizabeth Wiley lost her case. She was ordered to pay around $1,000 of the damages because a judge determined that the warrant for the raid didn’t specify a time, place, or purpose. Wiley stood by her public statement on the raid and continued her earnest efforts to reform and enforce the laws of Greybull.

Image

Election of 1928

When the election of 1928 came around, Wiley did not want to run for a third term. Despite her scandal and failure in her second term, Wiley remained popular. Her party insisted she run, and, as one newspaper reported, “Citizens at a mass meeting […] said they would not permit her to retire.” With less than a week before the election, Wiley jumped into the race for mayor, opposing Sam Pritchett. Pritchett’s campaign charged Wiley’s administration with inefficiency. In her closest race for mayor, Lizabeth Wiley won the seat by 22 votes, narrowly defeating Sam Pritchett.

Again, Lizabeth Wiley demonstrated her take-charge leadership. Spring 1929 found Greybull facing heavy snows followed by rapid melts. The floods of early March 1929 caused hundreds to flee their homes. Reconstruction of damaged roads and buildings began immediately, only for residents to have to evacuate again as flood waters returned. In desperation to escape the flood waters, one motorist ran over and killed a young child—the only casualty from the floods.

But the deluge of snowmelt left at least 35 families destitute, destroying homes and businesses. Property damage was estimated between $150,000 and $200,000. Personal loss was immeasurable in photographs and family heirlooms.

Like a captain on a sinking ship, Lizabeth Wiley remained in Greybull during the evacuation, retreating to the higher points of the town. After the flood, Wiley appealed to communities around Wyoming to raise relief funds and led relief efforts until the 1930 election, when she did not run again.

Still, she received a few votes. Wiley’s continued popularity was a result of her ability to stand strong in her convictions, face down opponents, take responsibility for her mistakes, and keep a tight budget.

By the end of Wiley’s political tenure, the second Klan had lost most of its following. The hypocrisy and moral failings of its leaders led many to abandon the organization, as well as its political failures. Wiley’s landslide election in 1924 and her unopposed run in 1926 sent a clear message that the Klan was not welcome in Greybull. Fearless in her convictions, Lizabeth Wiley stopped cross burning and other Klan activity in Greybull simply because she believed that “it could be done.”

[Editor’s note: Special thanks to Leslie Waggener of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming for her insights on the Second Klan in Wyoming, to Rick Ewig, formerly of the AHC, for alerting us to the 1919 shirt advertisement, and to the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, for support that in part made this article possible.]

Resources

Primary Sources

- Lizabeth Wiley Correspondence 1923-1929, Grace Raymond Hebard Papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

- Beach, Cora M., Women of Wyoming. Cheyenne, Wyo., 1927, pp. 488-491

- Newspapers from the Wyoming Newspaper Project, Accessed between Oct. 10, 2021 and April 26, 2023.

- The Casper Daily Tribune 19 Dec. 1926

- The Casper Daily Tribune 03 Mar. 1927

- The Casper Daily Tribune 04 Mar. 1927

- The Casper Daily Tribune 25 Mar. 1929

- The Casper Daily Tribune 14 May 1930

- The Cody Enterprise And The Park County Herald, The Park County Herald 31 Dec. 1924

- The Cody Enterprise And The Park County Herald, The Park County Herald 12 May 1926

- The Glenrock Gazette 12 Apr. 1923

- Greybull Tribune, May 19, 1922

- Greybull Tribune 5 Jan. 1923

- Greybull Standard 6 Jan. 1923

- Greybull Tribune 12 Jan. 1923

- Greybull Tribune 9 Feb. 1923

- Greybull Tribune 9 Mar. 1923

- The Greybull Standard and Tribune 12 Dec.1924

- The Greybull Standard and Tribune 14 Mar. 1924

- The Greybull Standard and Tribune 16 May 1924

- The Greybull Standard and Tribune 2 Oct. 1925

- The Meeteetse News 21 May 1924

- Park County Herald 24 Dec. 1924

- The Riverton Review 1 Nov. 1922

- The Riverton Review 20 Dec. 1922

- The Riverton Review 27 Dec. 1922

- The Riverton Review 3 Jan. 1923

- The Riverton Review 10 Jan. 1923

- The Riverton Review 14 Feb. 1923

- The Riverton Review 21 Feb. 1923

- The Riverton Review 19 Sep. 1923

- Sheridan Journal 20 May 1926

- Sheridan Post-Enterprise 1 Aug. 1926

- Sheridan Post-Enterprise 20 Dec. 1926

- Wyoming State Tribune, Cheyenne State Leader 21 Dec. 1926

- Newspapers from Newspapers.com by Ancestry accessed between April 23-26, 2023.

- The Billings Gazette 12 Mar. 1927

- The Billings Gazette 19 Mar. 1926

- The Billings Weekly Gazette 11 May 1928

- The Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune 21 Mar. 1928

- The Journal 11 Mar. 1929

- The St. Louis Star and Times 04 May 1928

- The Salt Lake Telegram 11 Mar. 1929

- The South Bend Tribune 14 Sep. 1924

- Woman Citizen; New York Vol. 9, Iss. 5, (Aug 9, 1924): 22-24, Accessed via ProQuest on April 25, 2023

Secondary Sources

- Blasi, Brie. “This Great Struggle: African-American Churches in Rock Springs.” WyoHistory.org, accessed April 25, 2023 at https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/great-struggle-african-american-churches-rock-springs.

- Dinnerstein, Leonard. "Leo Frank Case." New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Aug 11, 2020, accessed April 27, 2023 at https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/leo-frank-case/.

- Gordon, Linda. The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017.

- “The Greybull Public Library History”, Greybull Public Library, 2017, accessed April 28, 2023, at https://www.bhcwylibrarysystem.org/_files/ugd/39f23c_b38371d669c94d8696df077d04b8cc95.pdfy.

- Larsen, Justine S.I. “Rise of the KKK: Political Rhetoric of the 1920s Ku Klux Klan in the West” (2018),Undergraduate Honors Capstone Project. Utah State University, accessed April 20, 2023, via Digital Commons at https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1445&context=honors.

- “Mapping the Second Ku Klux Klan, 1915-1940,” Virginia Commonwealth University, accessed April 23, 2023 at https://labs.library.vcu.edu/klan/.

- Neymeyer, Robert. “The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s in the Midwest and West: A Review Essay.” The Annals of Iowa, (Fall 1992): pp. 625-633, accessed Apr. 27, 2023, at https://pubs.lib.uiowa.edu/annals-of-iowa/article/id/5206/.

- Waggener, Leslie. “Cheyenne Women of the Ku Klux Klan.” Sept. 21, 2020, Discover History, blog of the American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, accessed April 28, 2023 at https://ahcwyo.org/2020/09/21/cheyenne-women-of-the-ku-klux-klan/.

Illustrations

- The photos of downtown Greybull are from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The portrait of Lizabeth Wiley is from Women of Wyoming, by Cora Beach (Cheyenne, Wyo.: 1927), v.1, p. 491. Used with thanks.

- The image of the sympathy card is from Box 26 in the Nellie Tayloe Ross papers at the American Heritage Center, via the AHC blog at https://ahcwyo.org/2020/09/21/cheyenne-women-of-the-ku-klux-klan/. Used with permission and thanks.

- The image of the clothing ad from the Casper Daily Tribune, July 19, 1919, is from Wyoming Newspapers. Used with thanks.