- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Hot Springs County, Wyoming

Hot Springs County, Wyoming

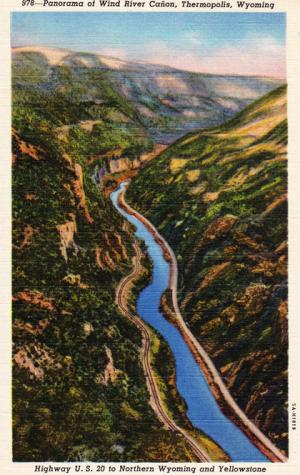

Hot Springs County is located in the southwest corner of the Bighorn Basin. Much of the county is mountainous, with the Owl Creek Mountains on the south and the Absaroka Range on the west. The northeastern part of the county opens into the Bighorn Basin. The Wind River, which enters rugged Wind River Canyon under its own name, becomes the Bighorn River when it emerges into the basin. The stream is the largest passing through Hot Springs County. Important tributaries are Owl Creek, Bridger Creek, Grass Creek and Kirby Creek.

The Owl Creek Mountains are made of warped and uplifted sedimentary rocks while the Absarokas are the remnants of a chain of extinct volcanoes. They were active in the Eocene, or roughly 45 million years ago. The Absaroka peak Washakie Needles, elevation, 12,518 feet, is the highest point in the county.

Outcrops of rocks near the Owl Creek Mountains from the Jurassic age, roughly 145 million years ago, bear fossils of dinosaurs, some of which are on display in the Wyoming Dinosaur Center in Thermopolis, Wyo. Younger rocks in the Absaroka range have many fossils of extinct mammal species such as the titanothere, a rhino-like creature with many short protuberances on its forehead and snout.

Several large hot springs rise near the mouth of Wind River Canyon and flow into the Bighorn River. These springs are similar to those in Yellowstone but are not caused by the same process. The Yellowstone thermal features come from heat sources relatively close to the surface; these hot springs result from structural geology that allows water to percolate deep in the earth, absorb heat, and then return to the surface through fractures. The five most abundant compounds dissolved in the hot water are bicarbonate, sulfate, chloride, sodium and silica, all present in concentrations of parts per million.

Prehistory

Many areas of Hot Springs County show evidence of prehistoric occupation, such as the petroglyphs incised or pecked onto weathered sandstone rocks with flint tools. Archaeologists attribute many of these petroglyphs to the ancestors of Shoshone people who live in Wyoming now, and believe that they probably had to do with visions, spirit power and vision quests.

The images represent humans, animals or creatures assumed to be spirits. Legend Rock, a cliff located in the central part of the county, displays some of the most spectacular such carvings in Wyoming. Bloody Hand Cave, near the mouth of Wind River Canyon, also has pictures and carvings.

Thermopolis and the hot springs

The large hot springs near present-day Thermopolis were sacred to the Shoshone people who recognized their therapeutic properties and thought of them as inhabited by spirits. These springs were one of the first attractions bringing white settlers to the future Hot Springs County; fur trapper Daniel Potts described them in a letter back home to Pennsylvania as early as 1826.

Later, after the Shoshone Reservation was established in the Wind River Valley in 1868, the hot springs were on the reservation. This meant that white settlers could not formally claim the land or erect permanent structures. It did not prevent numerous squatters from living near the springs in tents and dugouts, however, either to soak in the springs themselves or to sell food and lodging to others.

Thermopolis began in the 1880s near the mouth of Owl Creek, just outside the reservation boundaries of the time and downstream from the town's present-day site. It provided better quarters for visitors than the pole-and-brush "Hotel de Sagebrush" near the hot springs, and offered stores and other businesses to serve the ranchers and homesteaders on Owl Creek and along the river.

Just across the Bighorn River from Thermopolis was the town of Andersonville, where outlaws like Jim McCloud; Harry Longabaugh, known as the Sundance Kid; and Robert Leroy Parker, known as Butch Cassidy, appear to have visited regularly.

The fugitives probably chose the isolated area to thwart pursuers. Before the Burlington Railroad, building down from Montana, reached Thermopolis in 1910, people gained access to the area only by wagon roads over mountains from central or eastern Wyoming, or down from Montana. The first telephone went into service at Thermopolis in 1903, and the Western Union Telegraph Company arrived in 1907.

The “Gift” of the Waters

Each year the town of Thermopolis holds a pageant called "The Gift of the Waters" to portray the transfer of the springs from Shoshone ownership to the state of Wyoming. A member of the Shoshone tribe reads from a 1925 script: "I, Washakie, freely give to the Great White Father these waters beloved of my people. . . ."

Washakie, who died in 1899, was in fact chief of the Eastern Shoshone tribe for many decades before that. But what actually happened was a little more complicated. In 1896, Indian Inspector James McLaughlin of the Indian Service, a predecessor to today’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, came to the Shoshone Reservation, which since 1878 had included the Northern Arapaho tribe as well. (The name was changed to the Wind River Reservation in the 1930s.) McLaughlin came to negotiate an agreement with the tribes for the transfer of the springs to the federal government.

McLaughlin had been authorized to spend as much as $1.25 per acre, but he purchased 100 square miles of reservation land surrounding the springs for only $60,000, or about 94 cents an acre. Settlement and disturbance of the area around the hot springs had driven away game, decreasing the land's value to the tribes. The money and goods from this sale, elders hoped, would help the tribes in their transition to reservation life. There is no mention in any of the records kept of the 1896 negotiations that Washakie made a speech like the one in the pageant.

After this deal had been reached, the U.S. Senate decided not to accept the land. Wyoming Congressman Frank Mondell proposed a new arrangement in which the federal government would make the payments on the property, but the square mile containing the springs would be given to the state and the remaining 99 square miles would be opened for settlement.

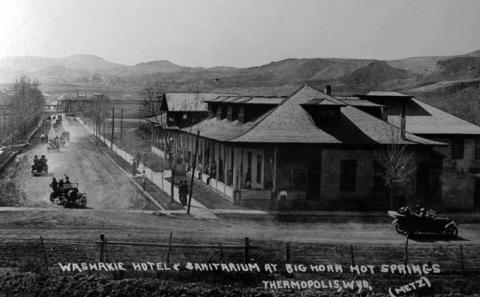

In 1897, Congress passed Mondell’s plan. Almost immediately, Hot Springs State Park opened and the town of Thermopolis was moved by its residents to the newly opened public land by the park. The water from the springs was piped into bath houses. Visitation increased, in spite of the difficulties of access to the area from other parts of the state.

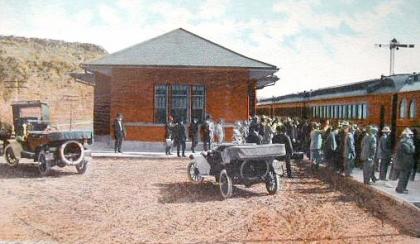

In 1910, the Burlington Railroad reached Thermopolis from the north. The first train, reported the Thermopolis Record, "included sixty or more people, and several dray loads of baggage and express were sent out...Quite a large number of people were on hand to see the train service started." The "Railroad Days" celebration began shortly afterward with horse races and other competitions that drew large crowds from the surrounding towns.

In 1911, the Burlington completed its line through Wind River Canyon to the south. This gave the entire Bighorn Basin much better connections with the rest of Wyoming. The resulting growth of Thermopolis, Worland and other towns led to the creation of Hot Springs, Washakie and Park counties out of parts of the original Big Horn County. On Feb. 9, 1911, the Legislature approved establishment of Hot Springs County with Thermopolis as county seat. County government was organized in January 1913.

Agriculture

Aside from the welcoming mineral waters, Hot Springs County’s mountains and arid plains seemed inhospitable for settlers. The daughter of Jess Hiram, a 1908 settler, told local historian Dorothy Milek of her father's first reaction on arriving at his uncle’s ranch on Owl Creek from Missouri. She said, "Dad got up, looked outside, turned to Uncle Hiram and said 'I just want to know—what did you do that you had to come here to hide. No one would live here if they didn't have to!'"

In spite of the hostile terrain, settlement began early. The first cabin in the Bighorn Basin was built by John Woodruff who trailed his cattle to a homestead on Owl Creek, the largest Bighorn tributary, in 1878. Other early cattle ranchers were Capt. R. A. Torrey, who started the Embar Ranch; Vincent Hayes, who started the Hayes ranch; and John McCoy with the Keystone Ranch. Much of this early settlement was along Owl Creek.

One of the first sheep ranchers in the area was Lucy Morrison, the "Sheep Queen," whose range in the 1880s was largely outside the basin, but extended to Kirby Creek north of Thermopolis. Sheepman Dave Dickie settled on Grass Creek in 1896 after armed cattle ranchers in present-day Washakie County prevented him from trailing sheep farther north to Canada.

After the winter of 1886-87, which decimated many large cattle ranches in Wyoming Territory, some of the Hot Springs County ranches closed down while others changed their operations to breed fewer but higher-priced cattle.

Farming also began several years prior to the creation of the future county. By 1900, ranchers were using ditches from Owl Creek to irrigate hay and alfalfa crops for livestock feed. However, because of high elevations and unsuitable land conditions, farming proved difficult for most and was never as significant here as in other parts of the Bighorn Basin.

Energy development

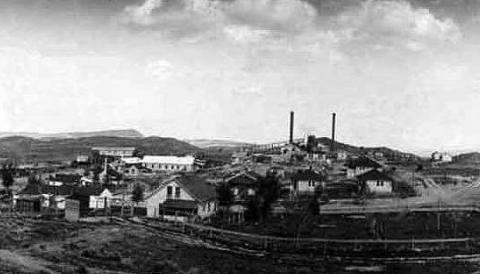

Coal was one of the first mineral resources to be developed in Hot Springs County. The Big Horn Collieries began mining deposits in 1898 near the future town of Gebo, a few miles southwest of Kirby. These mines helped bring the Burlington Railroad to Kirby in 1907. In 1910, Sam Gebo and his partners in the Owl Creek Coal Company began working in the same area.

Thirty-three claims covering a total of 13 sections were filed on Jan. 19, 1910, at the Lander land office. Most of these claims, says local historian Tacetta Walker, were filed under fictitious names or the names of dead people. They were intended to secure enough land that Gebo and his partners could attract financial backing. However, a federal investigation in 1912 led to all the claims being cancelled. Gebo and four partners were fined $1,500 each.

The coal lands were then leased by the federal government. By 1920, the town of Gebo, which housed miners and their families, had grown to a population of more than 2,000 people. Mining continued around Gebo until 1938, when financial losses and maintenance problems forced much of the operation to close. The remaining work ceased shortly after World War II, when railroads began using diesel instead of coal. By 1960, even the old buildings at the town site had almost disintegrated.

In the early 1900s, meanwhile, many of the early oil discoveries in the Bighorn Basin were made in Hot Springs County. Surface indications of domes, geological features that trap oil and natural gas, were prominent in the county. These areas were easy to discover and develop in the early days of oil exploration in Wyoming.

The Grass Creek Field northwest of Thermopolis, one of the largest in the state, was discovered in 1907. The Ohio Oil Company began substantial development in 1913 and the town of Grass Creek was founded. Mule-and-wagon freighters hauled equipment from the railroad at Kirby; according to historian David Wasden, it could be as expensive to haul the equipment as to drill the well. The town was successful, however, with a population that swelled to 500.

The town of Hamilton Dome, further northwest and named for Dr. A. G. Hamilton, one of the pioneers of oil exploration in Wyoming, was located at the oil field of the same name, discovered in 1915. The town of Grass Creek lasted until the 1960s; Hamilton Dome still had a rural school in 1986.

Depression years

During the Depression, energy development slumped in the county, and many workers lost their jobs in the mines or oil fields. As meat prices dropped, ranchers also suffered losses. President Franklin Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration, with projects like the maintenance of Hot Springs State Park, provided jobs for some.

Other men turned to bootlegging—selling illegal liquor—or poaching game to support themselves and their families. Bootlegging, especially, was almost commonplace in the county during Prohibition in the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1930, William Irving, state law enforcement commissioner, was convicted of accepting bribes from Hot Springs County moonshiners, among other charges, and sentence to 18 months in federal prison. A few county officials were also convicted on similar charges.

World War II

World War II brought on an energy boom and higher meat prices, which re-invigorated those parts of the county economy. The restrictions on gasoline and rubber, though, caused many to cut down on travel and reduced tourism to Hot Springs State Park.

Other types of rationing reached the Hot Springs County residents as well. "Tenderize your inexpensive cuts of meat…with cranberries," recommended an item in the 1942 Hot Springs Review. "With meat rationing just around the corner," another article in the same paper advised, "wild game of all types should be properly preserved...quick freezing and canning are two very satisfactory methods."

Reclamation projects

Several reclamation projects were built during and after World War II in this area of the state. All of these construction projects, while they lasted, gave jobs to many people in the county. In 1944, Boysen Dam, at the head of Wind River Canyon just south of the county line, was rebuilt, with concurrent improvements to the railroad and highway through the canyon.

For many years, officials discussed plans to dam Owl Creek. In 1956, Congress appropriated the money and a site was chosen on the Anchor Ranch. More than $5.35 million was spent on the project. Construction lasted three years, and the dam was completed in 1960. Unfortunately, the bedrock around the dam site was too permeable to hold water, a discovery made only after the project was finished. Anchor Dam stands today some 200 feet above a small pool.

Modern times

Tourism and energy remain as foundations of the Hot Springs County economy. Agriculture plays a lesser but significant role, with working farms and ranches scattered throughout the areas of lower elevation. Hot Springs State Park at Thermopolis incorporates hotels, public soaking pools, walking and biking trails and a free campground. The Wyoming Dinosaur Center in Thermopolis showcases fossils from throughout the world, many of them excavated locally. There are seven producing oil fields in the county—nearly a quarter of the currently operating fields in the entire Bighorn Basin.

Resources

Primary Sources

- "Did Herself Proud on Railroad Days," Thermopolis Record, June 30, 1910, 1.

- "First Train Out Monday," Thermopolis Record, June 16, 1910, 1.

- "Gift of the Waters," Thermopolis Record, Oct. 1, 1925, 1.

- Potts, Daniel. Letter to Robert Potts, July 16, 1826. Accessed Nov. 28, 2012 via http://user.xmission.com/~drudy/mtman/html/pottsltr.html.

- "Tenderize Meats," Hot Springs Review, Nov. 21, 1942, 1.

- "Wild Game Important Food," Hot Springs Review, Nov. 21, 1942, 1.

Secondary Sources

- "Coal Mining Exhibit." 2012. Hot Springs County Museum and Cultural Center. Accessed Dec. 1, 2012 via http://hschistory.org/page_pathcoalmining/

- Donahue, James, ed. Wyoming Blue Book: Guide to the County Archives of Wyoming. Vol. 5, Part I. Centennial Edition. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Wyoming State Archives, Department of Commerce, 1991, 313-316.

- Francis, Julie and Lawrence Loendorf. Ancient Visions: Petroglyphs and Pictographs from the Wind River and Bighorn Country, Wyoming and Montana. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2002, 1-32.

- Hot Springs County Planning and Zoning Commission. "Hot Springs County Land Use Plan." 2002. Accessed Oct. 31, 2012, at www.hscounty.com/upload/File/20080811_538_land_use_plan_1.doc.

- Lund, John. "Thermopolis, Wyoming." 1993. Accessed Dec. 6, 2012, at http://geoheat.oit.edu/pdf/bulletin/bi039.pdf

- Milek, Dorothy. Hot Springs: A Wyoming County History. Basin, Wyo.: Saddlebag Books, 1986, 129-275.

- -----. The Gift of Bah Guewana: A History of Wyoming's Hot Springs State Park. Thermopolis, Wyo.: Hot Springs County Bicentennial Project, 1975, 29-41, 169-178.

- O'Gara, Geoffrey. What You See In Clear Water: Life On the Wind River Indian Reservation. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2000, 1-23, 38-43, 270 n.11.

- Sundell, Kent. Geology of the Headwater Area of the North Fork of Owl Creek, Hot Springs County, Wyoming. Laramie, Wyo.: The Geological Survey of Wyoming, 1982, 1,17,32.

- Walker, Tacetta. Stories of Early Days in Wyoming: Big Horn Basin. Casper, Wyo.: Maverick Press, 2004, 29-35, 91-127, 201-231.

- Wasden, David. From Beaver to Oil: A Century in the Development of Wyoming's Big Horn Basin. Cheyenne, Wyo.: Pioneer Printing and Stationery Co., 1973, 110, 261-277, 286.

- Woods, Lawrence. Wyoming's Big Horn Basin to 1901: A Late Frontier. Spokane, Wash.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1997, 219-247.

- Wyoming Places. "Explore Wyoming by Clicking on the Map" Accessed Dec. 3, 2012 at http://wyld.sdp-sirsi.net/maps/

- Wyoming Home Town Locator. "Wyoming Cultural Features: Oilfields." Accessed Oct. 31, 2012, at http://wyoming.hometownlocator.com/features/cultural,class,oilfield.cfm.

Illustrations

- The photos of Gebo and of the Washakie Hotel at Thermopolis are from the Wyoming State Archives, by way of Wyoming Places. Used with thanks.

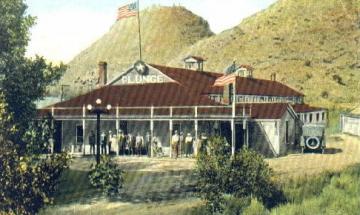

- The photos of the state bath house, the Burlington depot and the Star Plunge are from Wyoming Tales and Trails. Used with thanks.

- The 1940s postcard of Wind River Canyon was mailed on June 24, 1946 to Mrs. Carrie Hegery, Grainfield, Kansas, and reads on the back,

Mammoth Springs Yellowstone Park

Dear Mamma,

Spent the day driving through this. Really having a good time. We will go to “Old Faithful” tomorrow. Have a lovely cabin. We surely were lucky to get one inside of Park.

Love, Westlie - The photo of the view from Roundtop is by Jonathan Green, from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.