- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Ham’s Fork Crossing

Ham’s Fork Crossing

In southwestern Wyoming, Ham’s Fork is a principal tributary of Blacks Fork of the Green River. Presumably, it was named for mountain man Zacharias Ham of William Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company, who trapped in the area during the early 1820s. There were two Oregon/California Trail crossings of the Ham’s Fork. One was on the Sublette Cutoff of the near present Kemmerer, Wyo., and the other near present Granger, Wyo. on the main branch of the trail to Fort Bridger. The second of these is the focus of this article.

Coming from the northwest, Ham’s Fork flows into Blacks Fork, coming from the southwest, near Granger. Fort Bridger is located on the upper Blacks Fork about 30 miles southwest of where the two forks join. Blacks Fork then continues east to the Green River—Flaming Gorge Reservoir at that point—10 or so miles south of present Green River, Wyo.

The trail normally crossed near the junction of the two streams, although the precise site was not fixed and moved up or down Ham’s Fork depending on conditions. Usually, it was an easy crossing.

William Clayton described the area in his guidebook, The Latter-Day Saints’ Emigrants’ Guide,on July 6, 1847: “Ham’s Fork, 3 rods wide, 2 feet deep. Rapid current, cold water, plenty of bunch grass and willows, and is a good campground.” The wagons made this crossing with ease.

After several snowy winters, however, emigrants in 1849 and during the early 1850s found a far different stream, especially if they arrived early in the season. Ham’s Fork then was high and swift. A local mountain man operated a profitable ferry, as attested to by William J. Clark on June 2, 1849: “[T]raveled fourteen miles to Blacks Fork, followed up another four to Hams Fork where we ferried our things in a skiff of rough architecture two dollars per load. Had to swim our horses, river forty yards wide. Ferry kept by half-breed Indians and French. Traveled three miles and camped on Blacks Fork.”

William Johnston arrived about two weeks later. Though he seems to have crossed at a different location from Clark, his company found the stream still too high to ford easily. On June 15, 1849, Johnston wrote: “By measurement we ascertained that to ford it without damaging our goods in our wagon, it was necessary to elevate their beds a few inches; and further to aid in crossing we were obliged to use ropes, these being fastened to the forward axles, and carried to the opposite shore; while with others tied to the mules in the lead they were kept from being borne down stream by the rapid current. In all this we succeeded admirably, although at the outset we feared that we should be necessitated to ferry across as at Green River.”

In July, Ansel McCall found a stream more in keeping with Clayton’s description. On July 12, 1849, McCall noted, “[A]bout nine o’clock struck Ham’s Fork, a tributary of Black’s Fork, a beautiful little mountain brook, clear as crystal, rattling over a pebbly bed. Its banks were clothed with rich grasses and fringed with alder and willow.”

The ferry owner was back the next year and probably ran the ferry for about a month, when water was high. On June 8, 1850, Daniel Gardner arrived and ferried across, but it is unclear if his company used the commercial ferry. He wrote, “Thence to Hams Fork, a small stream sixty feet wide, very swift current. Too high to ford. We ferried our things in a wagon box and swum our horses and wagon. Here we came very, very near having one of our horses drowned by getting his feet entangled in the reins of his bridle. F swam in after him and came very near drowning himself.”

Silas Newcomb reached Ham’s Fork on June 28, and found the ferryman out of business, but apparently settling down for a longer stay. Newcomb found conditions a bit different from those recorded in Clayton’s guidebook, which he referred to, explaining that the water was deeper and the grass had been “eaten down and passed on.” He wrote that the water “wet our wagon boxes, though not to injure anything in the wagons. … Here also was the lodge of the now idle ferryman who had a squaw and several half breeds around–he had a large number of horses and oxen, cows & calves. Soon after leaving Ham’s fork we rose a small hill, and found on the left of the road a grave ‘N. Tharp, died Aug. 6th, 1849.’”

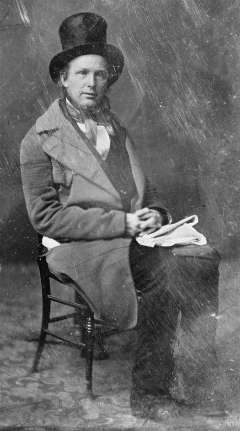

In 1857, during the so-called the Utah War, when President Buchanan sent U.S. troops to the Salt Lake Valley to re-establish federal control, the Army built a bridge at Ham’s Fork, but it was rarely used and short-lived. New York newspaperman Horace Greeley arrived on July 8, 1859, aboard the overland stage. He didn’t mention seeing a bridge, but did take notice of the locals Newcomb had seen nine years before.

“Eighteen miles [from the Green River] more of perfect desolation brought us to the next mail company’s station on Black’s Fork, at the junction of Ham’s Fork, two-large mill streams that rise in the mountains south and west of this point, and run together into Green River. They have scarcely any timber on their banks, but a sufficiency of bushes—bitter cottonwood, willow, choke-cherry, and some others new to me—with more grass than I have found this side of South Pass. On these streams live several old mountaineers, who have large herds of cattle which they are rapidly increasing by lucrative traffic with the emigrants, who are compelled to exchange their tired, gaunt oxen and steers for fresh ones on almost any terms,” Greeley wrote.

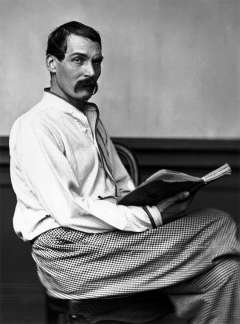

The mail station and future Pony Express and telegraph station was in a small cove on the north side of the stream and was described well by British travel writer Richard Burton, who arrived there on Aug. 22, 1860. Like Greeley, Burton was traveling in a stagecoach.

He was often unimpressed by the stations or their keepers, but thought he had discovered a new low at Ham’s Fork: “At mid-day we reached Hams Fork, the north-western influent of Green River, and there we found a station. There pleasant little stream is called by the Indians Turugempa, the “Blackfoot Water.” The station is kept by an Irishman and Scotchman—“Dawvid Lewis:’ it was a disgrace; the squalor and filth were worse almost than the two–Cold Springs and Rock Creek–which we called our horrors, and which had always seemed to be the ne plus ultra of western discomfort. The shanty was made of dry-stone piled up against a dwarf cliff to save back-wall, and ignored doors and windows. The flies–unequivocal sign of unclean living!–darkened the table and covered everything put upon it.” Station keeper David Lewis was actually a native of New York, but his two wives, sisters, were from Scotland.

From Ham’s Fork the trail continues southwest past Church Butte and after about 30 miles reaches Fort Bridger.

Resources

- Antilla, Jacob W. and Alice. History of the Upper Hamsfork Valley. Salt Lake City, Utah: Smith Printing Co. 1972.

- Burton, Richard F. The Look of the West, Overland to California. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1963.

- Clark[e], William J. Diary, 1849. Elko, Nevada. Undated typescript. Northeastern Nevada Genealogical Society.

- Clayton, William. The Latter-Day Saints’ Emigrants’ Guide. Stanley Kimball, ed. Gerald, Mo.: The Patrice Press, 1983.

- Gardner, Daniel B. Journal to California. Transcribed by Richard Rieck. MS 703, Shelf 21. Library of Congress.

- Greeley, Horace. An Overland Journey, from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859. Charles T. Duncan, ed. New York, N.Y: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964.

- Johnston, William G. Overland to California. Oakland, Calif.: Biobooks, 1948.

- McCall, Ansel J. The Great California Trail in 1849: Wayside Notes of an Argonaut.Bath, N.Y: Steuben Courier Printing, 1882. Photocopy.

- Newcomb, Silas. Overland Journey from Darien, Walworth County, Wisconsin, to Sacramento, California, 1850. Typescript. MS 359, Beinecke Library.

Illustrations

- The photos of Richard Burton and Horace Greeley are from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the Ham’s Fork Crossing is from the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Used with permission and thanks.