- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Esther Hobart Morris, Justice of The Peace and ...

Esther Hobart Morris, Justice of the Peace and Icon of Women's Rights

In late 1869, the territory of Wyoming was ahead of the rest of the United States in its strides for gender equality. Fifty years before the passage of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, women in the territory were granted the right to vote and, beginning with Esther Morris, the territory’s first female justice of the peace, to hold public office.

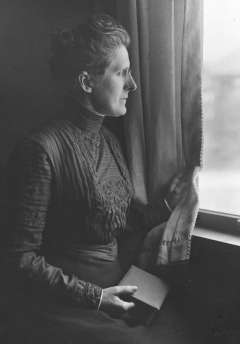

![Esther Hobart Morris was in her late 50s when she was appointed justice of the peace in South Pass City, Wyoming Territory, in 1870. '[I]n performing these duties I do not know as I have neglected my family any more than in ordinary shopping,' she wrote the following year, 'and I must admit that I have been better paid for the services rendered than for any I have ever performed.' Wikipedia.](/sites/default/files/styles/small/public/morris1_0.jpg?itok=mu8GVAGA)

While Morris is notable because of her excellent performance in this office and her advocacy for women’s suffrage both in the territory and, later, around the nation, much of her fame comes from something she almost certainly didn’t do. Long after Morris’s death, Fremont County legislator Herman Nickerson and University of Wyoming Professor Grace Hebard claimed that Morris deserved credit for effective lobbying in 1869 that resulted in the introduction of the women’s suffrage bill at the territorial legislature. This, however, seems not to have been what happened.

Born Esther Hobart McQuigg, in Tioga County, New York, on Aug. 8, 1814, she was orphaned at age 11 and apprenticed to a seamstress. She then, according to a brief biography at the website of the U.S. Capitol, became a successful hat-maker and businesswoman. In 1841, she married civil engineer Artemus Slack and gave birth to her first child, Edward Archibald or “Archy,” a year later.

Three years after the wedding, her husband died and Morris moved to Peru, Ill. to settle his estate. Doing this, she faced difficulties as women were not allowed to own or inherit property, the Architect of the Capitol writes. She re-married in 1850 to local merchant John Morris and gave birth to twin boys, Robert and Edward. In 1869, the family moved to gold-rush boom town South Pass City in the new Wyoming Territory, where John Morris opened a saloon.

The “terror of all rogues”

Esther Morris had been living in South Pass City for less than a year before her appointment as justice of the peace in early 1870 at the age of 55. During her eight and a half months in office as a judge, she heard nearly thirty cases.

Wyoming Territorial Secretary Edwin M. Lee wrote later that Morris’s court sessions were “characterized by a degree of gravity and decorum rarely exhibited in the judicature of border precincts.” He also said that during her administration, an “improvement in the tone of public morals was noticeable.”

An April 1870 piece in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper—a national publication—about Morris’s first day in the position focused, first, on her clothing. She wore “a calico gown, worsted breakfast-shawl, green ribbons in her hair, and a green neck-tie.” Later, however, the newspaper noted that Morris offered “infinite delight to all lovers of peace and virtue” and nicknamed her the “terror of all rogues.”

In January 1871, Morris was invited to a national women’s suffrage convention in Washington, D.C. but did not attend. Instead, she wrote a letter to prominent suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker which was read aloud before the convention. She wrote that her appointment, due to the circumstances in the political climate, “transpired to make [her] position as a justice of the peace a test of a woman’s ability to hold public office.” She also wrote that she felt that her work was “satisfactory” though she regretted that she was “not better qualified to fill the position. Like all pioneers,” she noted, “I labored more in faith and hope.”

By 1890, when she was 75, Morris was well known in Wyoming as an advocate of woman suffrage. In statehood celebrations that July, she presented the flag of the new state to Gov. Francis Warren on behalf of the women of Wyoming. She died at 87 on April 2, 1902, in Cheyenne.

A reputation grows

More than seventeen years after her death, however, her reputation suddenly began to grow.

Herman Nickerson, who had been one of the early pioneers of South Pass City and later served many years as a state legislator representing Fremont County, published in the Lander-based Wyoming State Journal his first-hand account of a supposed tea party.

According to Nickerson, Morris hosted a tea party in 1869 for South Pass City’s two candidates for Wyoming’s territorial council––William Bright and Nickerson himself. In front of a crowd of dozens of people, Morris supposedly extracted promises from both men that whichever of them won the seat would introduce a women’s suffrage bill to the new council. Bright was elected, proposed the bill and on Dec. 10, 1869, Territorial Gov. John Campbell signed it into law

“[T]o Mrs. Esther Morris,” Nickerson wrote, “is due the credit and honor of advocating and originating women's suffrage in the United States.” He explained that “there were about forty ladies and gentlemen present” at the party.

At the end of his account, he noted that he did not write it for “political purposes” but “to correct historical misstatements.”

But Nickerson appears to have been making some misstatements of his own. His account in the Wyoming State Journal implies that only he, the Republican, and Bright, the Democrat, were running for a single seat on the territorial council. In fact, seven candidates were running from Sweetwater County, where South Pass City was located at the time, for three seats in the upper house in the new territory’s legislative body. Bright was the third highest vote-getter with 747 votes, and so won a seat on the council. Nickerson came in fifth, and did not.

Bright and all the members of both houses of that first territorial legislature were Democrats. One reason the suffrage bill succeeded may have been their desire to embarrass the governor, a Republican. But he surprised them by signing the bill.

There is no record of any meeting between Morris and Bright before the election. After the bill was passed, however, Morris and her son did pay a call on Bright back in South Pass City, to thank him for his efforts. The son, Robert Morris, wrote a letter about the visit to The Revolution, a weekly magazine that advocated for women’s rights.

While she was alive, Morris credited Bright with passage of the bill. In her 1871 letter to Hooker, she wrote that “to William H. Bright belongs the honor of presenting the woman suffrage bill.” In that letter, too, there was no mention of a tea party.

Nickerson and Hebard

While Morris did not credit herself for the passage of the suffrage bill, others, long after she and Bright had both passed away, claimed it for her.

After Nickerson’s account was published, University of Wyoming professor and historian Grace Raymond Hebard rallied by his side, hoping to credit Morris for the introduction of the bill. Nickerson and Hebard were friends, and had spent many days and miles marking historical sites around Wyoming.

He may have been looking to advance the status of Wyoming’s Republican party at a time when women were 18 months away from winning the vote nationwide.Nickerson, that is, may have been hoping to extend some credit for the passage of the original bill to his own party.

For her part, Hebard was a staunch supporter of women’s rights and Esther Morris made a convincing hero. Contemporary historians now agree, however, that Hebard made things up from time to time. Historian Virginia Scharff labels Hebard a “self-described feminist” who did everything she could to “stake women’s claim to space, to historical significance.”

Hebard clearly championed Morris as the “Mother of Woman Suffrage.” According to Hebard, Morris and Bright held discussions about women’s rights around fireplaces in their homes. Hebard credited these conversations with giving Bright the inspiration and the final courage to introduce the women’s suffrage bill. In later stories Hebard changed the tea party into a dinner party.

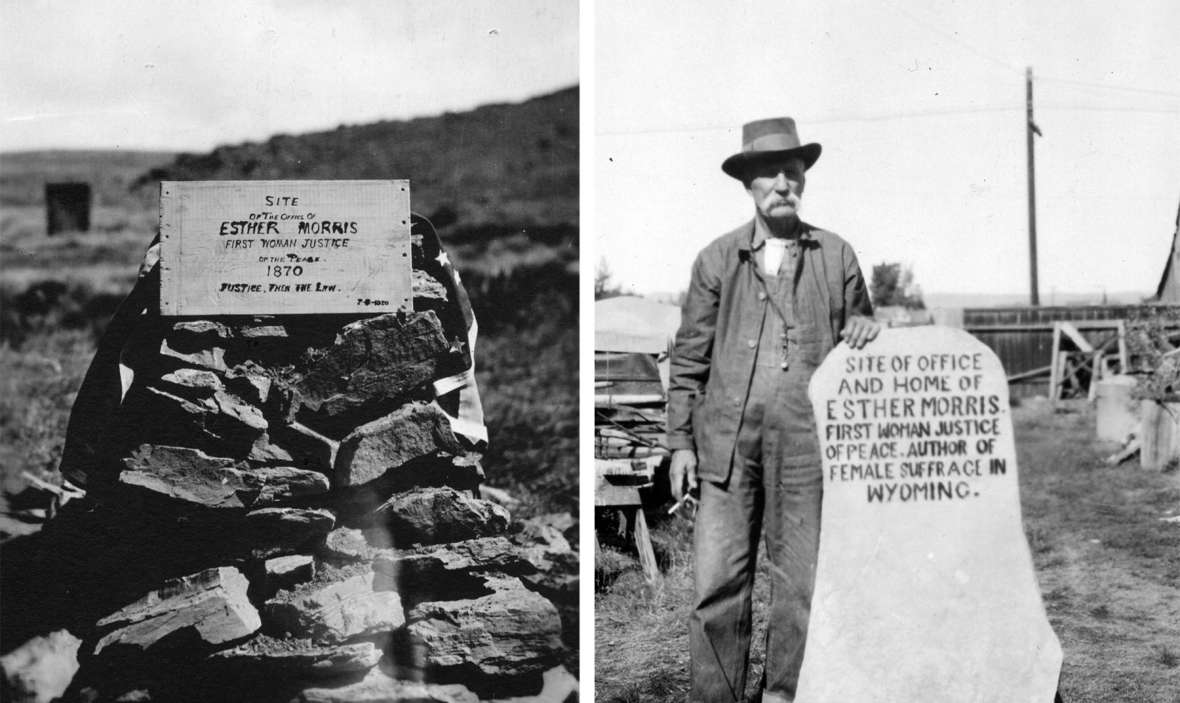

In 1920, Hebard and Nickerson had a stone marker erected in South Pass City memorializing the “Site of Office and Home of Esther Morris, First Woman Justice of the Peace, Author of Female Suffrage in Wyoming.”

The tea-party story continues

Though no contemporary records document the tea party, longtime women’s suffrage leader and president of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association Carrie Chapman Catt, in her Women's Suffrage and Politics; the Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement, published in 1923,writes that Morris invited all candidates for the council and persuasively presented “the woman’s case.” Each candidate then pledged to support a suffrage bill if elected. Catt and Hebard were frequent correspondents.

In Morris’s obituary in the Cheyenne Leader,there was no mention of her role in the suffrage movement. The piece, however, was later reprinted as a pamphlet with new additions saying that Morris was “instrumental in securing the passage of the law.”

In 1953, Wyoming’s U.S. senator, Lester Hunt, proposed that a statue of Morris be erected in the National Statuary Hall in Washington D.C. States were each allowed two statues; Morris was to be Wyoming’s first. University of Wyoming History Professor T.A. Larson objected to the decision, not believing the tea party had happened. Larson wrote in his History of Wyoming that one who introduces a bill “normally” gets credit for it and that Bright was clearly credited when he was alive.

In 1960, a statue of “Mother Morris” was erected in Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol. To this day, she is one of only nine women in the hall. This statue, to Larson, was placed “thanks to the upstaging” of Bright by Morris. On the Capitol’s website, The Architect of the Capitol notes only that with the statue, “Morris is honored as a pioneer for women’s suffrage.”

In 1963, a duplicate of the statue was erected in front of the Wyoming State Capitol in Cheyenne. When the Capitol reopened in 2019 after a four-year remodel, the Morris statue had been moved inside, to the Capitol Extension, the expanded underground space between the Capitol and the Herschler building.

“Future authors, teachers [and] historians,” writes longtime Wyoming historian Rick Ewig, “need to follow Esther’s lead, and not award her credit” for passage of the suffrage bill, “which she did not claim, and for which there is no supporting evidence.” Ewig’s article in the Winter 2006 Annals of Wyoming is one of the main sources for this piece.

Resources

Primary Sources

- Catt, Carrie Chapman. Woman Suffrage and Politics, the Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement. Buffalo, N.Y.: Hein, 2005, 75.

Secondary Sources

- Anderson, Jessica. "Overlooked No More: She Followed a Trail to Wyoming. Then She Blazed One." The New York Times. May 23, 2018, accessed Aug. 07, 2019 at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/23/obituaries/overlooked-esther-morris.html.

- "Esther Hobart Morris." Architect of the Capitol, accessed Aug. 07, 2019 at https://www.aoc.gov/art/national-statuary-hall-collection/esther-hobart-morris.

- “Esther Morris Turns 50.” Wyoming State Archives blog post Dec. 30, 2013, accessed Aug. 29, 2019 at https://wyostatearchives.wordpress.com/tag/esther-morris/.

- Ewig, Rick. "Did She Do That? Examining Esther Morris' Role in the Passage of the Suffrage Act." Annals of Wyoming 78, no. 1 (Winter 2006): 26-34.

- Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 78-94.

- Mackey, Mike. "Grace Raymond Hebard: Shaping Wyoming's Past." WyoHistory.org. November 29, 2014, accessed Aug. 07, 2019 at /encyclopedia/grace-raymond-hebard-shaping-wyomings-past.

- Roberts, Phil. "Wyoming Almanac and History of Wyoming." Everything About Wyoming - New History of Wyoming, Chap. 5, Territory and Suffrage, accessed Aug. 22, 2019 at http://wyomingalmanac.com/history_of_wyoming/new_history_of_wyoming_chap_5_territory_and_suffrage.

- Scharff, Virginia. Twenty Thousand Roads: Women, Movement, and the West. Berkeley, Calif: Univ. of California Press, 2003, 67-114.

Illustrations

- The portrait of Esther Hobart Morris is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

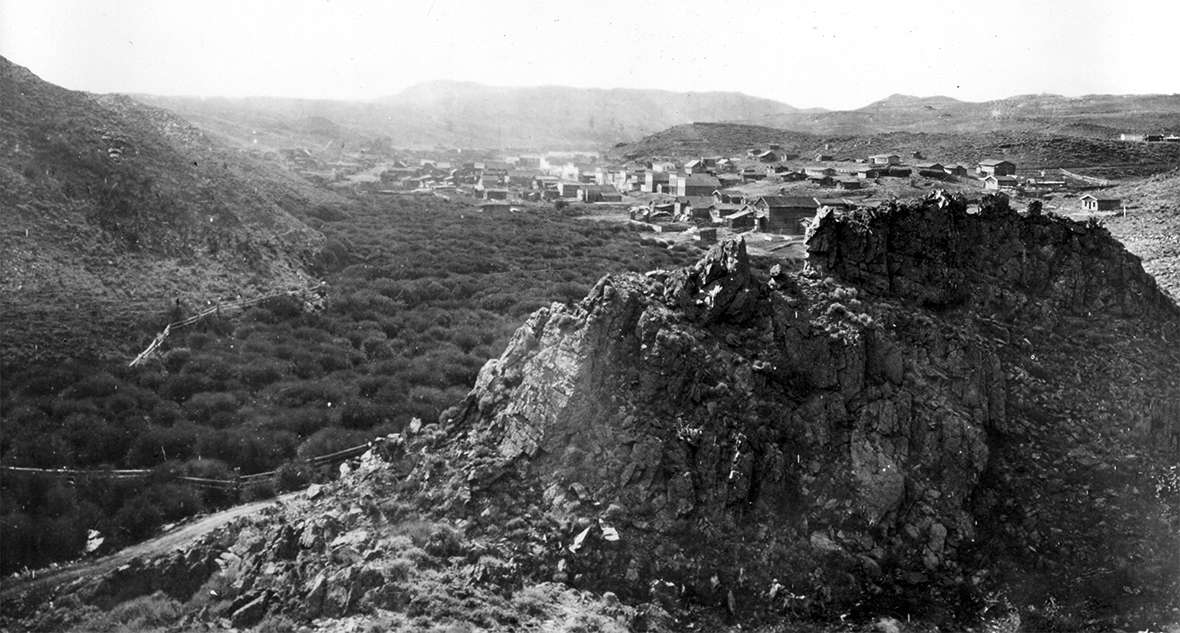

- The 1870 William Henry Jackson photo of South Pass City is from the U.S. Geological Survey’s online photo library. Used with thanks.

- The photos of Grace Hebard, Herman Nickerson and the two markers at South Pass City are all from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Esther Morris statue is from the Architect of the Capitol’s website. Used with thanks.