- Home

- Encyclopedia

- The Deadly Blackwater Fire

The Deadly Blackwater Fire

Fifty years after witnessing one of the deadliest forest fires in the nation's history, Bob Johnstone could still remember the screams of the young men at Blackwater Creek about 35 miles west of Cody, Wyo.

"We wanted to see if we could help get these [firefighters] who were trapped," recalled Johnstone, who, as an 18-year-old in the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, was on the Blackwater fire line. "We could hear those people below us, but we couldn't get down there to help them. ... It was a terrible thing. I hate to tell you some of the grisly things about it."

The fourth deadliest wildfire in the nation's history, the Blackwater Creek fire was started by a lightning strike in the pine-filled Shoshone National Forest on Aug. 18, 1937. The fire smoldered and crept through the ground fuels for two days before it was spotted by the owners of a local hunting camp. It covered about 2 acres; by the time it was controlled four days later it had consumed 1,700 acres.

At about the same time on Aug. 20, seven CCC enrollees returning from a work detail saw the fire crowning into the treetops and decided on their own to begin scraping a fire line at the base of the blaze. The crew's initiative spared the local men at hunting and tourist camps who normally fought forest fires in the Shoshone from having to leave their jobs during the busiest month of the year.

The CCC camp at Wapiti, about 25 miles west of Cody on the road to Yellowstone National Park, was alerted about the fire at 3:30 p.m. Within 20 minutes, 70 CCC enrollees and rangers from the camp were moving toward it. By nightfall the blaze had grown to 200 acres, and firefighters were constructing a fire line around it. Despite only light winds, the canyons pumped air to the fire and pushed spot fires ahead of the main one.

Investigators who later analyzed what happened pointed to several factors that impeded the efforts to contain the fire. There were no radios, so men had to carry notes between the various crews to relay information about where spot fires were cropping up and increasing in intensity because of adverse weather conditions.

Shifting weather

On Aug. 21, weather observers in Idaho told the Riverton, Wyo., weather office that a storm front with strong winds was moving into the Blackwater Creek area. That vital information was given to U.S. Forest Service managers at the Wapiti ranger station. But the lack of radios prevented the station from telling firefighters about the dangerous weather coming their way.

Poor phone communication was another problem. Investigators later determined it, too, probably played a role in the deaths of several firefighters who found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time when the fire went out of control. The Ten Sleep CCC camp in the Bighorn National Forest, far away across the Bighorn Basin, was ordered to send about 50 CCC enrollees and Forest Service personnel to Blackwater Creek, to arrive no later than 8 a.m. the next morning. But there was an unexplained three-hour delay between the attempted phone call notification and when it was received.

By daybreak 120 men were working the fire, but the Ten Sleep crew was nowhere in sight. The Ten Sleep CCC enrollees were meant to serve as fresh reinforcements for those who had been battling the fire since the previous night. But the new men, who traveled more than 180 miles over rough roads in the dark, did not reach the fire until about 11:30 a.m. They were given a quick meal, outfitted with hand tools and marched toward the east fire line, which was being constructed in a canyon that had numerous ravines and moderate to steep slopes with a gradient of 20 to 60 percent.

The fire was blowing in a northeasterly direction, overtopping Trail Ridge to burn in green timber on the other side. Prevailing winds made this area the fire's “hot spot." The forest was dense and mature with heavy fuel loads from dead trees with dead limbs extending to the ground. The situation provided a fuel ladder for fire to leap easily into the treetops.

Fire investigators later speculated that if they had arrived on schedule, the Ten Sleep crew members could have already extended the fire line past this treacherous area when the fire turned deadly and trapped them.

Inexperienced firefighters, rough terrain

The CCC members from the Ten Sleep camp were all Texans with little experience fighting fires. Three months before they were transferred to Wyoming, they had been in their home state helping create a park, establishing bridle paths and stocking lakes with fish. Their new Forest Service supervisors, however, were all experienced firefighters ready to guide them in their Cowboy State assignment.

Forest Ranger Urban Post and Junior Forester Paul Tyrrell led the way for the CCC party, with Ranger Al Clayton and Foreman James Saban taking the rear. They crossed a draw with a small trickle of water where Post detailed one man to remain and build a small dam to impound water for the backpack pumps. Because of the rough climb ahead, the men were told to carry their backpack pumps only half-full.

By 12:40 p.m., aerial observers reported seeing several spot fires near the east and west fire lines. It was 90 degrees, with the relative humidity at only 6 percent. Despite these tinderbox conditions, Ranger Post later recalled he was still optimistic they could get the relatively small fire under control. The fire was barely smoking, and his men were in good spirits. All they had to do, he thought, was extend the fire line to connect with a natural firebreak created by a rocky ridge to the northeast.

Ranger Post left six men to assist Clayton, who only had one firefighter with him, then led his 40-man crew east up a ridge. Clayton and his crew continued to suppress small fires that were spotting over fire lines started earlier by a Bureau of Public Roads crew.

From his higher vantage point Post could see more spot fires below. Clayton saw them too and his small crew quickly went to work to put them out. Recognizing the potential hazard, Clayton wrote a note to Post and gave it to a CCC enrollee to deliver.

The note read, "Post, We are on the ridge in back of you and I am going down to the spot in the hole. It looks like [the fire] can carry on over the ridge east and north of you. If you can send any men, please do so, since there are only eight of us. Clayton."

But the note seeking reinforcements didn't reach Post until it was too late for Clayton and his men. The dry weather front approached at 3:30 p.m., and steady 30 mile-per-hour winds blew from the southwest. Fifteen minutes later, the wind shifted abruptly to the west, causing increased crowning, with the fire leaping from treetop to treetop, and even more spot fires. Gusts reached 45 mph and whipped the flames into a raging firestorm racing east up ravines and gullies, trapping Clayton and his crew. The 45-year-old ranger and six of his men died, and another later succumbed to his injuries in the hospital.

“We have no safer place”

Post’s crew found themselves in an equally dangerous spot. If they were to save themselves, they had only one option: Abandon the fire line, find an escape route and run for their lives. When the wind suddenly pushed the fire back toward the southwest, Post ordered his crew to head northeast to a ridgeline, where they took cover on a rocky outcropping as fire swept over the ridge. They moved around to avoid each successive wave of heat and fire, but soon the rocks below them grew unbearably hot. Their flesh blistered and their clothing caught on fire.

"The heat is terrific, and it seems unbearable, but we have no safer place," Post later wrote about the terrifying ordeal. "If this is the end, we must take it here."

"Tops of the trees swung in the strong wind which was coming up through the basin, spot fires developed between the large spot fire and the main fire, and the wind had reached our line almost at once, and the large fire was a furnace immediately," Post recalled. "... Some of us wait for Tyrrell and the last ones out. The smoke is thick, the air is hot; we hurry up the ridge. Heavy tools are left behind. We take lady shovels, Pulaskis and canteens – we may need them for our own protection." A Pulaski is a tool used for constructing firebreaks that combines an axe and an adze in one head.

Post and his foreman, James Saban, ordered their CCC crew to stay down, but some panicked and refused to remain low while others sat up to say prayers. The 24-year-old Tyrrell bravely pinned three men to the ground, shielding them from the heat. But five other men decided to risk running into the flames, hoping to reach safety on the other side. It was a horrible choice: Four did not make it alive–Billy Lea, a Bureau of Public Roads crewman, and CCC enrollees Clyde Allen, Ernest Seelke and Rubin Sherry. The fifth man did survive but he was badly burned.

Since no one in Clayton's crew survived, their actions as the firestorm swept through the area are unknown. One fire inspector speculated Clayton may have taken some of the men with him to check a spot fire, while the rest waited for the requested reinforcements from Post's crew that were never sent. Once he discovered the danger ahead, Clayton may have tried to lead them back up a gulch toward a streambed, but based upon where the ranger's body was found he probably did not make it before fire overtook the entire crew.

Altogether, the fire killed 15 firefighters–all eight in Clayton’s crew and seven in Post’s unit. Ten CCC enrollees, all Texans between 17 and 20 years old; one was their foreman. Three of the deceased worked for the Forest Service and one was an employee of Wyoming’s Bureau of Public Roads. Thirty-eight more men were burned, many of them badly.

Recovering bodies

By 5 p.m. the worst of the fire was over, but the smoke was so thick the survivors in Post's crew who could walk stayed in place for nearly three more hours before leaving the site.

In the morning hours of Aug. 22, the bodies of Clayton and six of his men were found within 30 feet of each other. Sixty feet away rescuers found CCC enrollee Roy Bevens, who was badly burned but clinging to life. "God, how lucky I am to be alive!" he told the men who evacuated him to Cody, but he later died of his severe injuries at the hospital.

The solemn scene of the bodies Clayton's crew being taken from the forest was recorded by a Cody news reporter. "Seven pack-horses, each with angular forms wrapped in canvas and lashed to the saddles, filed slowly out of the wooded ravine and stopped at the cars," the journalist wrote. "Over a hundred wide-eyed, ashen-gray youngsters, just ready to go to the fire line, pushed forward, drawn by a chilling magnetism to see what their former comrades looked like."

What they witnessed that day stayed with the men, who were haunted by the deaths. In 1987, on the 50th anniversary of the Blackwater fire, CCC firefighter Lloyd Hull described that horrific afternoon. "It baked everybody below [the tree-top fire]. The heat was so intense," Hull remembered. "You knew it was happening. There was no 'figure' to it. We knew it."

Hull was part of the team that searched for bodies and helped the injured. So was 17-year-old Vernon Pitt, a just-discharged CCC enrollee from Cody who volunteered to stay and help.

"There was no way they could get out," Pitt said. "It was a pretty sad deal. Them boys was all young boys."

Morris Simpers, superintendent of the CCC's Cody camp, said when Clayton's body was discovered it appeared remarkably unscathed. Then he described how the ranger's woolen clothing crumpled into ashes when it was touched.

"Clayton's men could have walked to safety within seven minutes," Simpers later told the Billings Gazette. "That shows how fast the fire came up."

Ten of the casualties were young members of the CCC. The five others killed were employed by the U.S. Forest Service. Thirty-eight other men were injured. Putting out the fire took a back seat to the search for victims, but afterward fresh crews numbering up to 500 attacked the fire. It was officially contained three days later on Aug. 24, and the final firefighting crew was disbanded a week afterward.

Changes in firefighting

The Blackwater Creek Fire is a distant memory in wildfire history, but it led to an important change in the way forest fires would be fought in the future. David P. Godwin of the U.S. Forest Service's Division of Fire Control investigated the fire and determined the foremen and supervisors admirably performed their duties and were not to blame for the tragedy. It was beyond their control.

But Godwin questioned delays in the travel times of firefighting units, particularly the one dispatched from Ten Sleep. The investigator speculated that if they had arrived as scheduled, the Texans who left the Ten Sleep camp would not have been deployed where they were when the fire blew up. In his report Godwin noted in that scenario they may very well have survived unharmed.

Godwin ultimately concluded units needed to be on the scene much earlier, and two years after the Blackwater fire he authorized funds to carry out parachute jumping experiments linked to fire suppression. The federal government's smokejumper program, initially tested in Winthrop, Wash., and at two locations in Montana, was born.

On the second anniversary of the Blackwater Creek fire, 500 local residents helped dedicate a 71-foot-long stone monument, which contains the names of all the men who were killed or injured. It is located 38 miles west of Cody on U.S. Highway 14/16, near the junction of Blackwater Creek and the North Fork of the Shoshone River.

Two smaller monuments, accessible only by hiking or horseback on a 12-mile-round-trip trail, were built by CCC crews. One is located at the renamed "Clayton Gulch," and the second is at "Post Point," which fittingly marks the spot where Ranger Post and his men sought refuge. Post received the nation's first forest-fighting medal for leading his men to safety.

Clayton, meanwhile, was honored in a lengthy 1937 poem, "Alfred G. Clayton, Requiescat in Peace." It is credited to "L.C. Shoemaker and Roosevelt." The poem concludes:

"A hero? Oh no! just a ranger

Who answered unquestioned the call;

Whose motto -- like ours -- was service;

Who gave to 'The Service' his all.

And a promise we give to his loved ones,

That as long as rangers shall ride,The name of Alfred G. Clayton

Will still be remembered with pride."

Killed in the Blackwater Fire:

- Alfred G. Clayton, Ranger South Fork District, Shoshone National Forest, age 45.

- James T. Saban, CCC Technical Foreman - Ten Sleep Camp F-35 (former Forest Ranger on Medicine Bow and Chippewa National Forests), age 36.

- Rex A. Hale, Junior Assistant to the Technician, Shoshone National Forest; from the Wapiti CCC camp, age 21.

- Paul E. Tyrrell, Junior Forester, Bighorn National Forest (Foreman), died Aug. 26 at hospital, age 24.

- Billy Lea, Bureau of Public Roads Crewman, originally from Oregon, died later at hospital.

- Civilian Conservation Corps Enrollees: Ten Sleep Camp F-35 in the Bighorn National Forest; Company 1811 -- 3 months earlier came from Bastrop area of Texas, ages 17 to 20 years:

- John B. Gerdes of Halletsville, TX

- Will C. Griffith of Bastrop, TX

- Mack T. Mayabb of Smithville, TX

- George Harold Rodgers of George West, TX

- Roy Bevens of Smithville, TX, died later at Cody hospital.

- Clyde Allen of McDade, TX

- Ernest Seelke of LaGrange, TX

- Rubin D. Sherry of Smithville, TX

- William Whitlock of Austin, TX, died later at Cody hospital.

- Ambrocio Garza of Corpus Christi, TX, died later at Cody hospital.

Resources

- Always Remember website. “1937 08/21 WY15-Fatality Blackwater CCC.” Accessed May 15, 2016 at http://www.wlfalwaysremember.org/incident-lists/255-blackwater.html. Includes the list of the deceased, reproduced here.

- Forest Army: Remembering the Civilian Conservation Corps. “Death on the Fireline: The Blackwater Fire of 1937.” Accessed May 15, 2016 at http://forestarmy.blogspot.com/2007/08/death-on-fire-line-blackwater-fire-of.html.

- Howard, Tom. “CCC Reunion: 'Never Forget Fire.’” Billings Gazette, June 29, 1987.

- Kaufman, Erle. “Death in Blackwater Canyon.” American Forests, November 1937, 534-540, 538-539. Accessed June 21, 2016 at http://www.fireleadership.gov/toolbox/staffride/downloads/lsr5/lsr5_death_in_blackwater_nov1937.pdf. Good article published just three months after the fire, with photos of the Blackwater Creek terrain. If document does not load, copy and re-paste url directly into address window.

- Perry, Dave. “The Fatal Blackwater Fire.” Riverton Ranger, June 30, 1987

- Wikipedia. “Blackwater Fire of 1937.” Accessed June 29, 2016 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackwater_fire_of_1937

- For Further Reading and Research

- Gabbert, Bill. “Blackwater Fire of 1937 Remembered.” Wildfire Today, May 15, 2012. Accessed June 30, 2016 at http://wildfiretoday.com/2012/05/15/blackwater-fire-of-1937-remembered/.

- Gabbert, Bill. “Commemoration of the 75th Anniversary of the Blackwater Fire.” Wildfire Today, August 17, 2012. Accessed June 30, 2016 at http://wildfiretoday.com/2012/08/17/commemoration-of-the-75th-anniversary-of-the-blackwater-fire/.

Illustrations

- The photos of the firefighters monument and of the burned firefighters in hospital were both produced by Hoskins Studio, of Cody, probably in the late 1930s and are now in the collections of the Park County Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- Archives staffers caution that the photo of the burned men and their nurse was identified by its donor as being of firefighters injured in the Blackwater Fire, but the print itself contains no information on the back that would make that identification more certain.

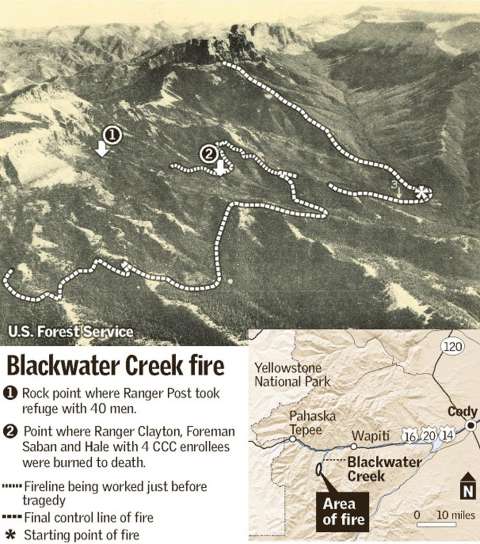

- The aerial photo of the Blackwater Fire is from the U.S. Forest Service. The U.S. Forest service map and graphic about the Blackwater Fire was reproduced on Wildfire Today. Used with thanks.

- The advertisement for backpack water pumps for firefighters was published alongside the 1937 Erle Kauffman article in American Forests, cited and linked in the bibliography above. Used with thanks.

- For 30 more Forest Service photos of the Blackwater Fire and its aftermath, click here.