- Home

- Encyclopedia

- Bill Nye, Frontier Humorist

Bill Nye, Frontier Humorist

Few Wyoming newspapers have names as arresting as Laramie’s. Go to the newspaper’s home page on the web, and you will find: “Laramie Boomerang: Laramie’s Voice Since 1881.”[1] But the page provides little else about the paper’s origins or those of its name. In fact, the newspaper and its name were established by a man who resided in the state less than seven years but was, at one time, considered “Wyoming’s most celebrated citizen” and remains one of the state’s most famous historical figures.[2]

Bill Nye, more formally known as Edgar Wilson Nye, was the first editor of the Laramie Boomerang. He named the paper for his mule because of what he described as the “eccentricity of his orbit.”[3] As Nye’s son Frank said, something about the word “boomerang” piqued Nye’s imagination. “His mule, his mine, his newspaper, his [first] book [Bill Nye and Boomerang], all bore the trademark.”

Indeed, the mule and the paper were in close association early on. Originally housed in a shoe store, the paper soon moved to the more expansive loft of a livery stable. Its editor could be found by coming “up the stairs,” Nye said, “or you could twist the tail of the iron gray mule and take the elevator.”[4]

Nye’s signature was humor. As he later said, “I can write up things that never occurred with a masterly and graphic hand.”[5] But when he first arrived in Laramie from Wisconsin, his talents were neither well developed nor well known, although that soon changed. “Ideas rose from his mind like bubbles from champagne,” Nye’s son Frank later observed, but Wisconsin was too conservative for Nye. It took Laramie to pop the cork.[6]

Early life

Nye was born in 1850 in Maine, where his parents found farming difficult. The soil was rocky, Nye later explained, and the farms so upright and steep “they could be cultivated on both sides.” Nye accompanied his family two years later to what would become Hudson, Wis., where as he grew up they led a rural, humble life.[7]

He enjoyed writing plays, instigating pranks and playing hooky from school, but he disliked farming. Instead, he tried working as a miller, then as a schoolteacher. Successful at neither, he tried the law—“Every boy who wore a big hat and got tired easily with manual toil,” he said, “was set aside for the ministry or the law”—but he never passed the bar in Wisconsin.[8]

He tried newspapering as well but could only find temporary work. Nonetheless, a freelance article he wrote for the Chicago Times led a family friend to recommend him to a Cheyenne businessman who in turn referred him to J.H. Hayford in Laramie, where Nye stepped off the train in late spring 1876 with 35 cents in his pocket.[9]

A Laramie newspaperman

During his first year in Laramie, Nye took a position with J.H. Hayford’s Laramie Sentinel, studied the law and passed the Wyoming bar. He also was appointed justice of the peace and notary public for the 2nd Judicial District of Wyoming.

And, he married. His bride, Clara Frances Smith, a petite music teacher, came west anticipating introduction to Nye through family friends. They were married within a year.[10]

Between the occasional law client and even more infrequent commission work, Nye wrote short pieces for various newspapers, which in turn led to a column for the Denver Tribune and national exposure.

When he hired Nye in 1876, Hayford had been publishing a daily version of his Laramie Sentinel, a Democratic newspaper, for about a year. Nye worked two years for Hayford, a straight-laced newspaperman with a medical degree who later became a judge. “He gave me $12 a week to edit the paper,” Nye said. “He said $12 was too much, but, if I would jerk the press occasionally and take care of his children, he would try to stand it.”[11] Nye worked at the Sentinel two years. He said he might have stayed longer “if I hadn’t had a red-hot political campaign, and measles among the children, at the same time. You can’t mix measles and politics,” he said, so he collected his salary and quit.[12]

That’s the way Nye chose to remember it in his autobiography, Bill Nye: His Own Life Story (1926), a book Frank Nye assembled long after his father’s death. But there was more to it. For one thing, the fun-loving Nye and the officious Hayford didn’t see everything eye to eye. Hayford, who gave away the bride at Nye’s wedding, would later chastise Nye for not being serious in his journalism, even suggesting Nye “rub the donkey off his coat of arms.”[13]

A Boomerang humorist

For another, local Republicans, smarting from poor election results in November 1880, wanted a daily newspaper. Hayford was only publishing a weekly, and that did not compete with a new Democratic daily, the Daily Times.[14] So, they raised $3,000 to purchase a newspaper plant and paid Nye $150 a month to edit what became the Boomerang, a Republican sheet. They also gave Nye the county printing contracts, secured for him the Laramie postmaster’s job to supplement his income, and found space for the paper at the livery stable.[15]

Nye came at the end of an already long line of American funny men. Together, they had been developing an American-styled humor since the Revolution and employing the humorous techniques of burlesque, parody, puns, exaggeration, anti-climax and irony since the 1830s. The line can be traced back to Ben Franklin, but in the 19th century, it included such notables as Maj. Jack Downing, Petroleum V. Nasby, Davy Crockett and Mark Twain. Nye became for a time the most successful of them, although Twain remains far better known today. By the 1890s, thanks to the publication of more than 16 books, two plays and a national tour of stage performances, Nye was the nation’s best-known humorist, and at $30,000 a year, its highest paid.[16]

Like other American humorists, Nye deflated those who would be pretentious, vain, or pompous, exposed booster propaganda and wooed readers with local color, which he did not find in paying quantity until he moved to Laramie. As Wyoming historian T.A. Larson notes, Nye’s best material came from his time in Laramie. “His later humor, whether published in newspapers or books, rarely amuses,” Larson concluded, but “in earlier, happier days in the West, Nye had been really funny.”[17]

Indeed, material from his time in Laramie can still bring a smile. Like Twain and most everyone else who went West, Nye invested in mining prospects. As with Twain and most others, mining stocks never earned him a red cent, except as fodder for one of his funniest tales, titled “My Mine.” When he sent a specimen to be evaluated, Nye wrote, the assayer reported what he found: gold, nil; silver, nil; “railroad iron,” one ounce; “pyrites of poverty,” nine ounces; and “parasites of disappointment,” 90 ounces. The formation was “igneous, prehistoric, and erroneous,” said the assayer, who advised: “If I were you I would sink a prospect shaft below the old red brimstone and preadamite slag crosscut the malachite and intersect the schist. I think that would be schist about as good as anything you could do. Please send specimens and $2.”[18]

“Well,” said Nye, “I didn’t know he was ‘an humorist.’”[19]

Bursting the boomers’ bubbles

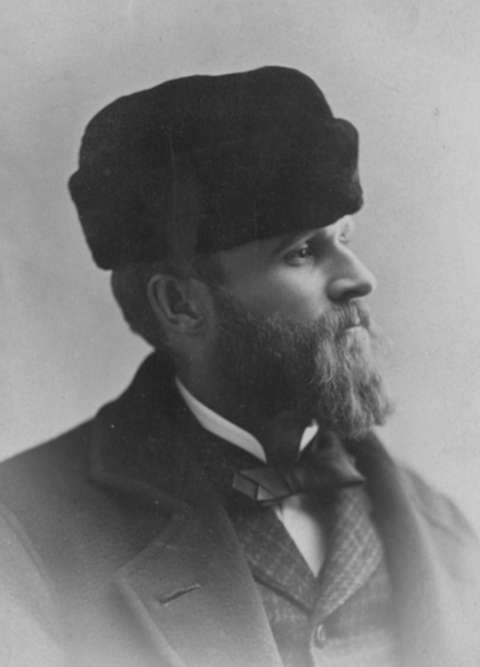

A tall, spare man with what his illustrator Walt McDougall termed “a lounging gait, blue-grey myopic eyes, and a sweet, wry smile,” and best known for his exceptionally bald head, exaggeration and understated self-deprecation, Nye made himself the butt of almost all his humor.[20] “It’s a lot funnier to call yourself names,” he said. “And besides, it’s a lot healthier in Wyoming.”[21]

By nature, Laramie seemed an exaggeration. At the time Nye was there, Laramie’s population numbered perhaps 2,500 souls. It had a burgeoning economy based on heavy industries, including machine shops and a steel mill rolling out rails for the Union Pacific Railroad. The town also had stockyards, a slaughterhouse, a glass-blowing plant, a plaster mill and a brewery. Lodged between the Laramie and Snowy mountain ranges along the Laramie River at almost 7,200 feet elevation, the city was founded less than a decade earlier in 1868, received less than 11 inches of moisture a year, and could record temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

For Nye, Laramie was a gold mine. He had, for example, Wyoming’s climate, and he had Hayford for a straight man. In classic boosterism, 19th-century newspapermen could write unmitigated exaggeration. Hayford, for example, claimed Wyoming’s weather to be a positive factor. He reduced Laramie’s winter storms to tropical breezes: “No other Rocky Mountain town presents as much attraction in the way of climate as Laramie City,” Hayford enthused. “Laramie City is the only one of all the towns in this region which is almost entirely exempt from hard winds. The blustering storms and howling winds spend their fury harmlessly in the mountains around us and above, while perpetual calm and sunshine bless the inhabitants below.”[22]

Nye delighted in bursting such bubbles. Describing the wind from one particular storm, he wrote: “The sun was hidden by clouds and also by flying fragments of felt roofing and detached portions of the rolling mill and machine shops.”[23]

Hayford and company boomed Wyoming’s agriculture absurdly and with straight faces. Hayford not only claimed that rain followed the plow, but that the iron tracks of the railroad attracted it as well.[24] Nye checked his reasoning. “I do not wish to discourage those who might wish to come to this place,” he wrote, but “the soil is quite coarse, and the agriculturalist, before he can even begin with any prospect of success, must run his farm through a stamp-mill.”[25] Winter, he said, “lingers in the lap of spring till it occasions a good deal of talk,” although in Laramie, he admitted, “it does not snow much, we being above snow line.”[26]

If Nye could “write up things that never occurred,” so could J.H. Hayford, but Nye never asked his readers to buy it as truth. Self-deprecation was impossible for Hayford, but it came naturally to Nye, who attributed his election as justice of the peace in Laramie to his ability to make people laugh. Or was the laugh on him? As he said, “I was elected quite vociferously, for the people of the West are a humor-loving people and entered into the thing with great glee.” And further, “While I was called Judge Nye, and frequently mentioned in the papers with great consideration, I was out of coal half the time.”[27]

National fame

Nye left Laramie in 1883, advised by doctors that he could not live at such a high altitude after being diagnosed a year earlier with spinal meningitis. Two of his books, Bill Nye and Boomerang (1881) and Forty Liars and Other Lies (1882), were published before Nye left town. Compiled mainly from Nye’s newspaper work in Laramie, they are what T.A. Larson regards as his funniest. A third volume, Baled Hay, (1884), which Nye is said to have clipped from the pages of the Boomerang’s office files just before he left, also drew from his Laramie newspaper work.[28]

Nye returned to Hudson, Wis., where he lived quietly and produced more material. He also began lecturing, which Larson regards as possibly “the worst mistake he ever made” because his lecturing, ever lucrative, drove him beyond his physical endurance.[29] After three years, Nye moved briefly to New York City and then to Arden, N.C., where he lived the remainder of his life.

Soon after leaving Laramie, he was hired as a columnist for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. On stage, he found great success with James Whitcomb Riley, the “Hoosier Poet.” Working together for four years—Nye with his deadpan humor and Riley with his nostalgic poems—they were even introduced one evening in Newark, N.J., by none other than Mark Twain. Nye hated the lecture circuit, however, and all but gave it up three months before his death on Feb. 22, 1896.[30]

To literary critics, Nye was said to be a realist, a trait hastened on him by his time in Laramie. Nye saw genuineness and forthrightness in western life, and he defended it against Eastern pretensions.[31] As O.N. Gibson would later note in the Annals of Wyoming, Nye “was a humorist, purely and simply. He possessed no poetic gift, no prophetic insight … He acknowledged no graver purpose, claimed no higher mission, than just to make men laugh.”[32] Gibson speculated whether that might be the reason Nye, even then in 1925, was not as well remembered as he otherwise might be.

In February 1896, however, Nye’s obituary ran in scores of newspapers across the nation. In another obituary, one written in 1926 by the beloved humorist Will Rogers for Montana’s cowboy artist, Charlie Russell, Rogers said to Russell: “I bet you hadn’t been up there three days till you had out your old pencil and was a drawing something funny about some of the old Punchers … I bet you Mark Twain and Old Bill Nye, and Whitcomb Riley, and a whole bunch of those old joshers was just a waiting for you to pop in with all the latest ones.”[33] The latest ones were a distinctly American type of humor that Nye knew well. American humor, he said,

crystalized by hunger and sorrow and tears … is not found elsewhere as it is in America. It is out of the question in England … an Englishman cannot poke fun at himself. He cannot joke about an empty flour barrel. We can: especially if by doing it we may swap the joke for another barrel of flour. We can never be a nation of snobs as long as we are willing to poke fun at ourselves.[34]

Few people ever said it better.

(Editor’s note: Publication of this and seven other articles on Wyoming newspapering is supported in part by the Wyoming Humanities Council and is part of the Pulitzer Prizes Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prizes Board and the Federation of State Humanities Councils in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the prizes. The initiative seeks to illuminate the impact of journalism and the humanities on American life today, to imagine their future and to inspire new generations to consider the values represented by the body of Pulitzer Prize-winning work. For their generous support for the Campfires Initiative, the council thanks the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes Board, and Columbia University.)

Resources

Primary Sources

- Laramie Boomerang. Accessed Feb. 9, 2016, at http://www.laramieboomerang.com.

Secondary Sources

- Gibson, O.N. “Bill Nye.” Annals of Wyoming, 3, no. 1 (July 1925): 96-97, 101.

- Kesterson, David B. Bill Nye: The Western Writings. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University Western Writers Series, 1976, 6-7.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 116, 119, 359-60.

- Larson, T.A., ed. Bill Nye’s Western Humor. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1969, v, vii-viii, xi, x, 26.

- Saum, Lewis. “Bill Nye in the Pacific Northwest.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 84, no. 3 (July 1993): 83.

- Nye, Bill, and Frederick Burr Opper. Baled hay: a drier book than Walt Whitman's "Leaves o' grass". New York: Belford, Clarke & Co., 1884.

- Nye, Edgar Wilson. “In Lighter Vein, Autobiography of an Editor.” The Century Magazine, 45, no. 1 (November 1892): 158, 159.

- Nye, Frank Wilson, Bill Nye: His Own Life Story, Continuity by Frank Wilson Nye. New York: The Century Co., 1926, 30, 41, 43-45, 48, 57, 60-63, 77-82, 89.

- Stone, Melville. A Book of American Prose Humor. Chicago: Herbert S. Stone Company, 1904, 82.

- Yagoda, Ben. Will Rogers: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993, 204.

Illustrations

- The line-drawing image of Bill Nye, from the frontispiece of Baled hay: a drier book than Walt Whitman's "Leaves o' grass," is courtesy of the author. The A.J. Russell photo of the UP roundhouse and machine shops is from the U.S. Geological Survey Denver Library Photographic Collection. Used with thanks. The photo of Bill Nye in cowboy garb is from the Rainsford Collection at the Wyoming State Archives, used with permission and thanks. The photos of the early Boomerang office and of Nye in a fur hat are from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks. The cartoon of the crow from Bill Nye's Comic History of the United States (1894) is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- Charles E. Rankin is associate director/editor-in-chief for the University of Oklahoma Press, a position he has held for sixteen years. Before that, he was director of publications for the Montana Historical Society and editor of Montana The Magazine of Western History. He earned a doctorate from the University of New Mexico in 1994 and is editor or co-editor of three books, one on Wallace Stegner, another on the Battle of the Little Bighorn and a third on the New Western History.

[1] Laramie Boomerang, http://www.laramieboomerang.com.

[2] O.N. Gibson, “Bill Nye,” Annals of Wyoming, 3:1 (July 1925), 96.

[3] Ibid., 97.

[4] Frank Wilson Nye, Bill Nye: His Own Life Story, Continuity by Frank Wilson Nye (New York: The Century Co., 1926), 77; Edgar Wilson Nye, “In Lighter Vein, Autobiography of an Editor,” The Century Magazine, 45:1 (November 1892), 158.

[5] Nye, Bill Nye, 44.

[6] Ibid., 45, 48.

[7] Gibson, “Bill Nye,” 97.

[8] Nye, Bill Nye, 30.

[9] Ibid., 41.

[10] Ibid., 60-63.

[11] Ibid., 43; T.A. Larson, History of Wyoming (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 116, n 16.

[12] Ibid., 43-44.

[13] Larson, T.A., “Laramie’s Bill Nye,” 1952 Westerners Brand Book (Denver: Arthur Zeuch Printing, 1953), 41.

[14] Ibid., 40. Burrage, F.S., “Bill Nye Leaped from a $12 Job to World Fame,” Laramie Republican-Boomerang, July 25, 1929.

[15] Nye, “Bill Nye,” 61, 77-82; T.A. Larson, ed., Bill Nye’s Western Humor (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969), v, vii-viii; David B. Kesterson, Bill Nye: The Western Writings (Boise, Idaho: Boise State University Western Writers Series, 1976), 6-7.

[16] Larson, Bill Nye’s Western Humor, viii.

[17] Ibid., xi. See also Davidson, Levette J., “’Bill’ Nye and the Denver Tribune,” Colorado Magazine, 4:1 (January 1927), 17; and Kesterson, Bill Nye: The Western Writings, 12-13.

[18] Nye, Bill Nye, 89; see also Melville Stone, A Book of American Prose Humor (Chicago: Herbert S. Stone ‘ Company, 1904), 82.

[19] Ibid.

[20] McDougall, Walt, “Pictures in the Papers,” American Mercury, 6:21 (September 1925), 72.

[21] Gibson, “Bill Nye,” 101; Nye, Bill Nye, 45.

[22] Larson, “Laramie’s Bill Nye,” 47; Larson, History of Wyoming, 119, 359-360. See also notes 16 and 17 on page 116.

[23] Denver Tribune, Jan. 18, 1880, in Davidson, “’Bill’ Nye and the Denver Tribune,” 16 and n 12.

[24] Larson, History of Wyoming, 119.

[25] Ibid., 359-360.

[26] Larson, Bill Nye’s Western Humor, 26.

[27] Nye, Bill Nye, 57.

[28] Larson, Bill Nye’s Western Humor, x.

[29] Ibid., viii.

[30] Ibid., ix; see also Lewis Saum, “Bill Nye in the Pacific Northwest,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 84:3 (July 1993), 83.

[31] Kesterson, Bill Nye: The Western Writings, 16.

[32] Gibson, “Bill Nye,” 101. On Nye’s diminishing reputation, see also Steven H. Gale, Encyclopedia of American Humorists (New York: Garland Publishing, 1988), 343; and Dumas Malone, ed., Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1943), 13: 599-600.

[33] Ben Yagoda, Will Rogers: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 204.

[34] Edgar Wilson Nye, The Century Magazine, 45:1 (November 1892), 159.