- Home

- Encyclopedia

- 1968: Wyoming Reacts To The King Assassination

1968: Wyoming Reacts to the King Assassination

As the year 1968 dawned, the page one headlines of Wyoming’s and the nation’s newspapers reported that President Lyndon Johnson had resumed the bombing of North Vietnam, further escalating dissent at home about the war. “U.S. Jets Return to North Viet, Hit Hanoi,” the Casper Star-Tribune’s headline read on Jan. 3rd. The report said U.S. forces had killed 348 Viet Cong the previous day.

Unfortunately, the year 1968 would also bring huge losses of American soldiers. That year saw by far the most American casualties in the Vietnam War of any, with 16,592 killed. Civil rights leader the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King had become a strong critic of the war, in part because African Americans were being drafted and killed at rates much higher than their proportion in the population.

But the big news in Wyoming on Jan. 2nd was about the University of Wyoming Cowboys, the only undefeated major college football team during the 1967 season, nearly beating Louisiana State University in the Sugar Bowl on New Year’s Day. On its front page, the Casper Star-Tribune headlined “New Orleans To Remember ‘Poke’ Fans,” and reported that “The Jung Hotel, official headquarters for the Wyoming Alumni Association, was totally unprepared to satisfy the thirsty needs of the free-spending Wyoming fans.”

Also in that issue of the Star-Tribune, “The Star-Tribune Thinks” editorial said recent anti-war demonstrations were “Communist-inspired stuff, basically. ... It is a cardinal Red tenet that nobody but Reds should have freedom of speech, because Reds possess all truth and all wisdom.”

In the early months of 1968, Dr. King’s name made only an occasional appearance in Wyoming newspapers. Several news items covered King organizing a Poor People’s March on Washington to occur in April. On March 7th, a UPI report noted King’s assertion that the purpose of the march was “to try to prevent riots. If nothing is done, I think the riots this summer will be worse than last summer.” King was calling for an “Economic Bill of Rights.”

But violence in the streets was on everyone’s mind in 1968. Riots in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles in 1965 were followed by riots in Chicago in 1966 and far more severe unrest in Detroit, Newark and dozens of other cities across the nation during the so-called “long hot summer” of 1967. That year, 83 people had died in civil unrest by early September.

On March 18, 1968, King told reporters he had no intention of running for any political office. But he said he would not vote for re-election of Democratic President Lyndon Johnson in the fall. Thirteen days later, the heavy weight of the never-ending Vietnam War forced Johnson to bow out, opening the field to Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. Many expected a rerun of the 1960 Kennedy vs. Nixon race, but this time Vietnam War critic Robert would be the Kennedy involved.

On March 20th, a syndicated column in the Casper Star-Tribune said Kennedy was counting on King’s march, slated to start April 22, to give his presidential ambitions a big lift. On March 29th, two southern senators warned that King intended to “build a powder keg” and that the march on Washington should be blocked at the city limits.

At the end of March the focus shifted to Memphis where King had joined 1,300 African-American city sanitation workers who had been on strike for seven weeks after two of them were killed in a trash compactor. They were seeking higher pay and safer conditions. On March 28, UPI reported that “Negro youths hurled rocks and bottles at helmeted policemen today on their way to join Dr. Martin Luther King’s sanitation strike march” in Memphis. The next day the Star-Tribune carried a report of a 16-year-old Black youth killed by a shotgun blast from a White policeman, and 62 others injured during disturbances in Memphis.

Speaking to an indoor crowd there on the evening of April 3, the 39-year-old King concluded his speech by saying, “I’ve been to the mountaintop. I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land!”

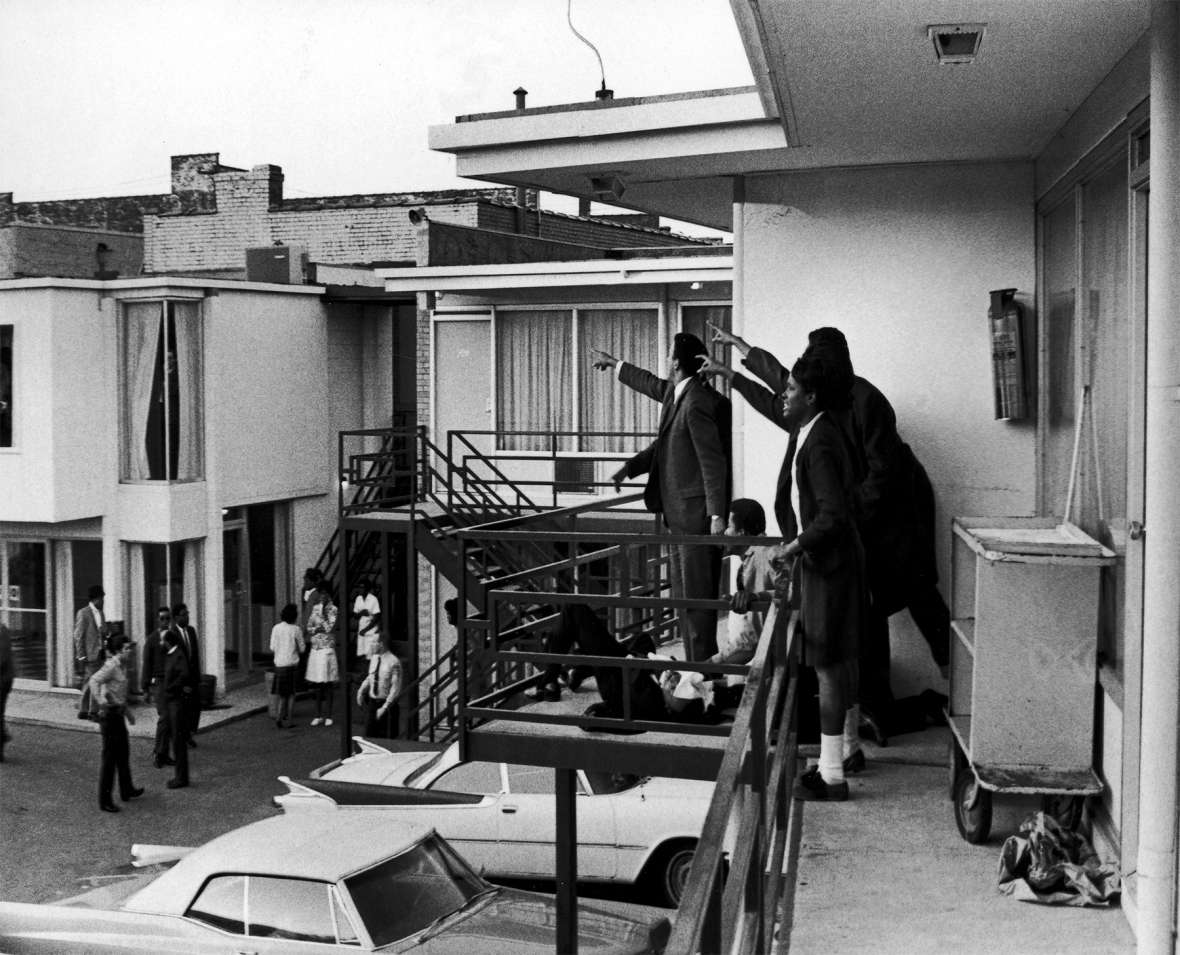

The next evening, escaped convict James Earl Ray, who had traveled from Atlanta to Memphis upon reading of King’s appearance there, and who had holed up in a rooming house across from the Lorraine Motel just waiting for an opportunity, shot and killed King as he was talking to his friends on the balcony of the motel. The motel is now part of the National Civil Rights Museum. The death brought demonstrations and destructive rioting to cities across America.

Reactions In Wyoming Newspapers

Editorials in Wyoming newspapers ran from sadness over King’s death to condemnation of the riots and the demonstrators.

The Laramie Boomerang’s editorial on April 6th, headlined “A Leader Is Lost,” said the death “shows to what lows the moral level of the United States has fallen. Before the summer is over, the white population of the United States may well suffer as the Negro and other minority groups have been made to suffer in the past. . . . Perhaps the death of King will serve to awaken the American people to the equality and equal rights they [African-Americans] claim are granted under the Constitution. Perhaps, somewhere in the not too distant future, a man may be judged on his ability and not on his color or race. Even the Mafia gets a better break now than does the Negro. We hope that Martin Luther King Jr. did not die in vain. We hope that decent Americans will come forward and take up the leadership he gave the Negro people and inspired in many others.”

On April 7, the Boomerang reprinted an editorial from the Denver Post which began, “In the history of the world’s injustice there are few spectacles more deserving of anger and of tears than the striking down of a man of peace and goodness by forces of violence and hate.”

Bob Peck, editor of the Riverton Ranger, on April 6th called it a “tragic assassination. ... Dr. King had a decade of leadership including some substantial triumphs dating back to the Montgomery bus strike that removed one of the many painful Jim Crow discrimination signs. He won world acclaim and received the Nobel Peace prize.” Peck said Dr. King faced “severe tests when he came north to try to provide leadership to break the grip of the ghettos which imprison the poorest Negroes in some of our cities.” Peck expressed hope that courageous leadership would bring the country out of the violence so that “Dr. King’s martyrdom may prove to be his final and greatest contribution toward the cause of brotherhood.”

Dave Bonner, editor of the Powell Tribune, on April 9th spoke of “the feeling of fear” that even people in “this relatively removed area of the West” were experiencing as rioting and looting in urban areas followed in the wake of King’s killing. The editor noted that two wrongs do not make a right and that no one had to accept rioting because of the assassination. Then the editor said: “But out of the death of Dr. King comes one realization of a debt that is owed. We owe it to a group of people to understand Civil Rights as our problem—not their problem. We owe it to a group of people to square up to the fact that black has been black and white has been white for too long in this country and that the two colors have walked in different lines.”

Before the assassination even occurred, one Wyoming commentator was already complaining about the demonstrations in Memphis. In the Jackson Hole Guide that hit the streets early on April 4th, Floy Tonkin said in her “Riding the Range” column: “THE ‘PEACEFUL’ PROTEST MARCH’ in Memphis called by and led by the Rev. Martin Luther King turned into a looting riot, and the Reverend took off hurriedly in a car. Since Mr. King is planning a peaceful poverty march to our nation’s capital, we suggest that business houses there start boarding up their windows.”

In her column a week later, the same columnist continued, “Then came the news of the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King and the terrible rioting of negroes in Washington, Chicago and other cities, with looting and burning. The black people lost more than a leader last week – they lost the respect and tolerance of the whites.”

James Griffith Jr., editor of the Lusk Herald who would later be elected as both Wyoming state treasurer and state auditor, noted in his column “Jim’s Jottings” on April 11th that he had spoken to two Wyomingites living in Washington, D.C., and he “received the same story from both – the looting, burning, sniping at foremen and attacking of policemen and others was largely done by young Negroes who could care little who Martin Luther King was. [T]he assassination ... was an excuse, not a reason, for violence. This action cannot be condoned, must not be tolerated, and should be dealt with forcefully and immediately. . . . However, the [rioters] are not the Negro community, but merely the lunatic fringe of a much larger and responsible group. We as a nation of compassionate people cannot condone or tolerate the hopeless and dire conditions in which many of these people live.”

In Cody, Wyo., 24 miles from Powell, the editor of the Cody Enterprise on April 11th gave no quarter to the concept that poverty, poor schools, employment discrimination and bad housing conditions disproportionately limited the ability of African-Americans to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps. The editor said the rioting “has done nothing to further the Negro cause.” If anything, he said, “even the moderate, tolerant people are being made more ‘set in their ways’ and adamant than ever before.” The editor acknowledged that “the Negro has not enjoyed equality in civil rights,” but this concession was immediately qualified by saying “this is not only true here, but true in almost every nation in the world which is not colored. ... Racial prejudice is a built-in part of life in this world.” The editor said civil rights such as fair taxation and a jury trial do not include “social rights” or “financial rights.” Legislating equal financial rights, the editor argued, was absurd. “They do not exist. The person with more ability, with more property, or with better luck, is normally going to fare better than the one lacking these qualities. ... Social, financial or any other privileges must be earned by the individual himself.”

The editor of the Wyoming State Tribune, the right-wing afternoon paper in Cheyenne, also was looking past the murder itself to the reaction. The editorial on April 5th, before Ray had been identified as the killer, began with the suggestion that it might have been Black radicals who murdered King. Editor James Flinchum then wrote that if the assassin was White, “he has served only the purpose of the black power radicals ... The fomenters of domestic unrest who have been using the civil rights movement and Negro unrest to create the massive civil disturbances in the United States of the past few years.”

The editorial next quoted from King’s statements through the years urging non-violence and said, “We are sorry he went to Memphis.... The important point is that his death has removed a major Negro leader, and also one who stood as an opponent of the urban riots.”

The next day, the Wyoming State Tribune’s editorial was headlined: “A Time for Action.” Printed with unusual double-spacing, the editorial warned: “It is not the first time rioters have swept through the streets of Washington, nor even burned down buildings. But it just might be the last. ... The time has arrived for a stern and fearless leadership that will say to one and all, whites and blacks, young and old, men and women: We must not and we will not tolerate any longer this violence and this lawlessness. It will be put down with every means at our command. ... To those of you who do not [quiet down], we shall deal with you in the harshest possible measures.”

Finally, on April 7, the Wyoming State Tribune condemned the “mass orgy of self-guilt in which America is now wallowing. ... The public display of emotion which has approached that of the Kennedy assassination has entirely obscured the issues .... In the midst of all this wailing, breast-beating and weeping ... some calm assessment of what has transpired and what is needed is in order.” The editorial then rejected calls for civil rights legislation and open housing laws, “plus more billions of dollars of free money from Uncle Sam.” The editors noted that the previous spending for those in urban “congestion centers” had “intensified if not actually accelerated the problems of the ghettoes.”

The editors of the Torrington Telegram, Evanston Herald, the Star Valley Independent in Afton and the Jackson Hole Guide made no mention of the assassination in editorials during the following two weeks.

On Tuesday April 9th, the Casper Star-Tribune said the “recent rioting” in American cities “should assure Senate passage of legislation to make the streets safer for the public,” providing funds to “improve police training and crime-fighting techniques.” The next day, the editorial said “the outpouring of tribute [surrounding the King funeral the previous day] was indicative of the basic values of America.”

The Casper Star-Tribune said all people “took hope from the tragedy that it might provide a gateway to a better understanding.” But the work to solve these problems, the editorial warned, “will not be done in a day. It will take a great deal of money .... Above all, it will take the willing cooperation of those whom it is designed to help. The white man alone cannot solve the black man’s troubles.”

Views from Wyoming’s Black Community

Six weeks before the assassination, African-American leaders in Wyoming attempted to warn state citizens about the desperation, hopelessness and anger of their people and the lack of concern by Congress and local governmental leaders. On Feb. 27, 1968, a long UPI article appeared in state newspapers quoting Johnnie McKinney, president of the Cheyenne branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, saying that Wyoming was not free of the conditions which could lead to rioting. "Unemployment in the ghettoes is of depression proportions, and the housing is unworthy of a wealthy nation—and surely an insult to the black veterans of our wars," McKinney said. He added that riots often were started by “hasty actions on the part of the police,” a premonition of events 52 years later after George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor was killed by police in Louisville, Ky.

In another UPI article two days later in the Casper Star-Tribune and the Rawlins Daily Times, Fred Devereaux, president of the Wyoming-Colorado Conference of the NAACP, said he agreed with McKinney. He said some 700-1,000 African-Americans lived in the north Casper area which he called "a ghetto" and that Casper was more concerned with planning for a civic center than with improving housing conditions. He said he and other NAACP leaders had recently met with Gov. Stan Hathaway and asked for more representation of Blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans on draft boards and on the Fair Employment Practices Commission.

In the same article, however, Cheyenne Police Chief James Byrd, one of the few Black police chiefs in the country, said his city had not experienced racial violence in the past and although “it’s impossible for me or anyone else to say flatly it can’t happen, I certainly don’t think it’s likely.”

A UPI report in the Casper Star-Tribune the day after the assassination quoted Devereaux as saying the murder of King “is one of the most horrible things that ever happened in this country. It’s really a disheartening thing.” In an April 11th Casper Star-Tribune report, Devereaux cautioned that the fact that Wyoming’s Black people had not engaged in rioting was not an indication that they were happy. They “are no different than the black people in New York, Chicago or anywhere else,” he said. “I feel that anyone who lives more or less trapped in an undesirable situation will feel that way. Most white people feel we’re pretty much under their heels.”

Devereaux joined some of the editors in saying the death of King removed a man “the militants would really respect. Now they will say, ‘Look, there’s a man who talked about non-violence and they took his life.’”

On Sunday evening, April 7th, the Casper Interracial Council held a memorial service honoring Dr. King attended by 700 people at the Natrona County High School Auditorium. Dr. Robert Fowler of the CIC minced no words in his presentation. He suggested that the motto should be changed to “hate your neighbor as yourself,” saying people don’t seem to have respect for themselves, much less anyone else.

Another speaker was the Rev. Orloff W. Miller, Director of the Mountain Desert District of the Unitarian Church, who compared King to a modern Moses saying “let my people go.” (Three years earlier, on March 9, 1965, Miller was with fellow Unitarian minister Rev. James Reeb, who grew up in Casper, when Reeb was attacked and killed in Selma, Ala., while supporting the voting rights movement. King gave the eulogy at Reeb’s service in Selma).

Barbara Banister and the Grace African Methodist Episcopal Church choir in Casper honored King’s memory with singing. Across the Casper Star-Tribune’s front page story on the service ran the headline, “Racial Violence Hits 80 Cities.”

On April 10th, the Casper Star-Tribune ran a column by syndicated conservative columnist James J. Kilpatrick urging Congress not to be stampeded into adopting the civil rights bill then pending. “The assassination provided no more justification for passing a bad law than it provides for looting a liquor store. . . [Black leaders] quickly transformed the tragedy into a general club to beat the Congress with.” This sentiment was adopted in the Star-Tribune’s editorial that day.

On April 15th, the Casper Star-Tribune ran a syndicated column by Robert S. Allen warning that Stokely Carmichael, “fiery advocate of racial revolution, bloodshed and destruction to bring this country to its knees” was trying to grab control of King’s “poor people’s march” on Washington. He said Carmichael was allied with groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality, which, he said, had “close Communist ties.”

Aftermath

The assassination of King postponed the Washington D.C. April march, but thousands of people came in June and camped on the Mall for six weeks. On June 8th, three days after his assassination at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral procession stopped at their “Resurrection City” before proceeding to his burial next to his brother at Arlington National Cemetery. In November, Vice-President Hubert Humphrey lost the presidential election to Richard Nixon, who had campaigned heavily on law and order.

In 1990, after eight earlier attempts led by longtime Cheyenne legislator Liz Byrd, the Wyoming Legislature finally passed and Gov. Mike Sullivan signed a bill making the third Monday in January a paid state holiday honoring King. As a compromise measure, the lawmakers named it “Martin Luther King/Wyoming Equality Day.”

Resources

Primary Sources

- Casper Star-Tribune, 1968: Jan. 2, p. 1, 4; Jan. 3, p. 1; Feb. 29, p. 2; March 7, p. 4; March 18, p. 12; March 28, p. 13; March 29, p. 1; April 5, p. 11; April 8, p. 1; April 9, p. 4; April 10, p. 4; April 11, p. 12; April 15, p. 4

- Cody Enterprise, April 11, 1968, p. 2.

- Jackson Hole Guide, April 4, 1968, p. 3; April 11, 1968, p. 3.

- Laramie Boomerang, April 6, 1968, p. 4; April 7, 1968, p. 4.

- Lusk Herald, April 11, 1968, p. 3.

- Oakland Tribune, June 9, 1968, p. 1-3.

- Powell Tribune, April 9, 1968, p. 4.

- Rawlins Daily Times, Feb. 27, 1968, p. 20; Feb. 29, 1968, p. 1.

- Riverton Ranger, April 6, 1968, p. 6.

- UPI report, Daily News Journal, Murfreesboro Tenn., March 21, 1968, p. 12.

- Wyoming State Tribune, April 5, 1968, p. 4; April 6, 1968, p. 4; April 7, 1968, p. 4.

Secondary Sources

- “Long, Hot Summer of 1967.” Wikipedia, accessed Oct. 12, 2020.

- White, Phil Jr. Wyoming in Mid-Century. Self-published 2020, pp. 104-106.

Illustrations

- The photo of the immediate aftermath of the King assassination was taken by Joseph Luow for LIFE magazine. Used with thanks to and permission from gettyimages.

- The 2005 photo of Bob Peck, longtime Riverton Ranger editor and state legislator, is from Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The Casper Star-Tribune photo of the April 7, 1968 King memorial service at Natrona County High School is from the Casper College Western History Center. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the boardinghouse window from which James Earl Ray is believed to have fired the fatal shot is from Wikimedia Commons. Used with thanks.