- Home

- Encyclopedia

- 1924: The Year The Banks Closed

1924: The Year the Banks Closed

When a person puts her money in a bank, she’s confident it will be there when she comes back. In the meantime the bank doesn’t just keep the money in a drawer. It uses it, lends it out most likely, to someone who needs it to buy a house, or start a business, or pay for college. The bank pays the woman a low interest rate for the privilege of using her money. It charges a higher rate to the people it lends the money to, and makes a profit on the difference between the two rates.

If the bank is well run, its owners feel obliged to the woman to keep her money safe. It will lend money, some of which is her money, only to people the bank employees are confident will be able to pay the money back. If the woman thinks about these things at all, she probably knows this. More likely, though, she doesn’t think about it because she’s convinced the money will be there when she returns, just as safe as if the bank had kept it in a drawer for her, the whole time.

Banking, that is, depends on peoples’ confidence in each other. It depends on the woman’s confidence in the bank, and on the reliability of the bank’s confidence in its loan customers. For a while in Wyoming in 1924 it looked as if those kinds of confidence might vanish entirely, and a lot of people would be left with no money at all.

A run on a bank

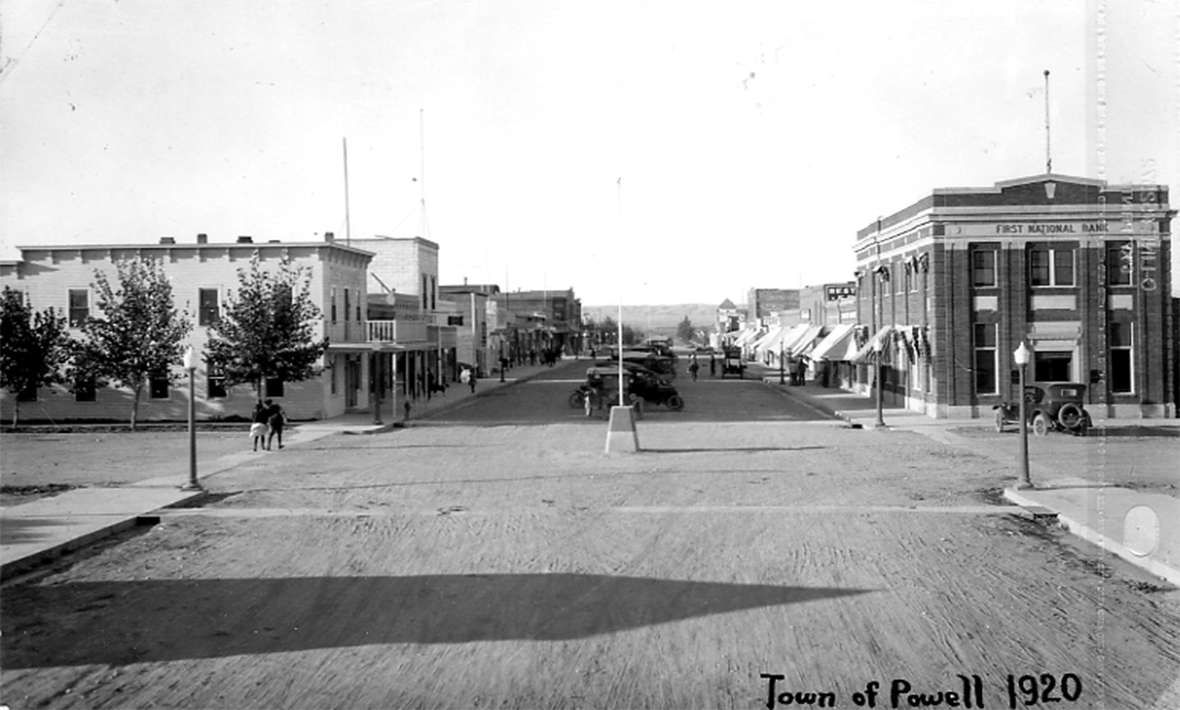

Severt Ambrose Nelson, president and chief owner of the First National Bank of Powell, was at home one Thursday evening in March 1924, when a knock came at the door. S.A., as his friends and family called him, was surprised to find on his doorstep Ed Dowling, his main business competitor in town. Dowling was president of the Powell National Bank. Let’s say Dowling stepped in the door to talk privately. He was nervous, declined any offer of refreshment, and got right to the point: Powell National would not open its doors in the morning, and he could not say when, if ever, the bank would open its doors again.

The hundreds of people who had deposited their money in his bank would not be able to get it out. They would be angry. Word would get around quickly. There was a good chance, both men understood, that once they heard the news, that Nelson’s depositors would want to pull their money out of his First National bank, too—just to make sure. A kind of panic could set in.

This is called a run on a bank, when large numbers of depositors all demand their money at once. A run could ruin a bank in a day. (A bank never keeps enough cash on hand actually to pay out to each depositor his entire account. Most of a bank’s transactions, in fact, don’t involve cash at all. Money comes in in checks or other kinds of bookkeeping records, and goes out the same way. These accounting methods amount to signed, legally binding promises—signs of people’s confidence in each other.)

But when people are worried about whether a bank will keep its promises, the sight of actual cash money can help. On Friday morning, S.A. Nelson told his tellers to pile all the bank’s cash in big stacks behind the counters. He hoped the simple sight of the money would give people the confidence to leave their money in the bank. But if they did demand the cash, here it was, ready to hand out as long as it lasted. A crowd had already gathered outside. Nervously, S.A. Nelson opened the doors.

Early-day banking

Banking in Wyoming had started even before Territorial times with people who needed a safe place to leave their money for a while. People would leave cash in an envelope with the owners of trading posts, stores at army bases or stores in towns. To pay a debt, a person could give a signed note to his creditor, the person he owed the money to. The creditor could take the note to the store, show it to the clerk, and collect money directly from the debtor’s envelope.

Soon it was simpler for the storekeeper to keep track of he deposits by entering the amounts in a record book, and then paying it out to whomever had a note from the depositor. From there it was a short step to running a bank, from which the storekeeper could make a profit on the money he was holding by lending some out at interest.

Early banks lent out money in the form of banknotes, bearing the name of that bank, directly to the borrowers. Borrowers could spend these notes as they needed, and people would keep on spending the notes—the notes would go into general circulation. This worked fine as long as people’s confidence in the bank stayed strong.

Financing the Civil War

More modern banking systems spread nationwide during the Civil War. Congress needed a reliable way to borrow money to pay for the war. During the war it passed a National Banking Act. Banks could officially become national banks if their owners could show they had capital of at least $100,000 to invest in the business.

With this money, the banks could buy government bonds—that is, lend money to the government. Those bonds would be deposited to the banks’ credit in the national treasury, and the banks could now issue bank notes secured by—that is, backed up by—the government bonds. A bank’s bank notes could now be backed by the government’s promise to pay back the money the bank had lent it by buying the bonds.

Besides making available the money Congress needed to fight and win the war, the new system of national banks also allowed the reliability of government finances to spread across the country. In general, national banks could attract more investment capital, and therefore more business, because they were so much more likely to remain reliable over time. The new system gave people more confidence, and banking could run more smoothly.

State banks

States and territories passed similar laws allowing the establishment of state banks. Usually these required less capital for the startup. In Wyoming Territory, banks planning to incorporate needed only $25,000 if they were in towns of fewer than 2,000 people, $50,000 if they were in towns of 2,000 to 5,000 people, and $100,000 only if they were starting up in towns of 5,000 people or more. Also in Wyoming, there were plenty of private banks. These had no startup requirements, and were not subject to any laws.

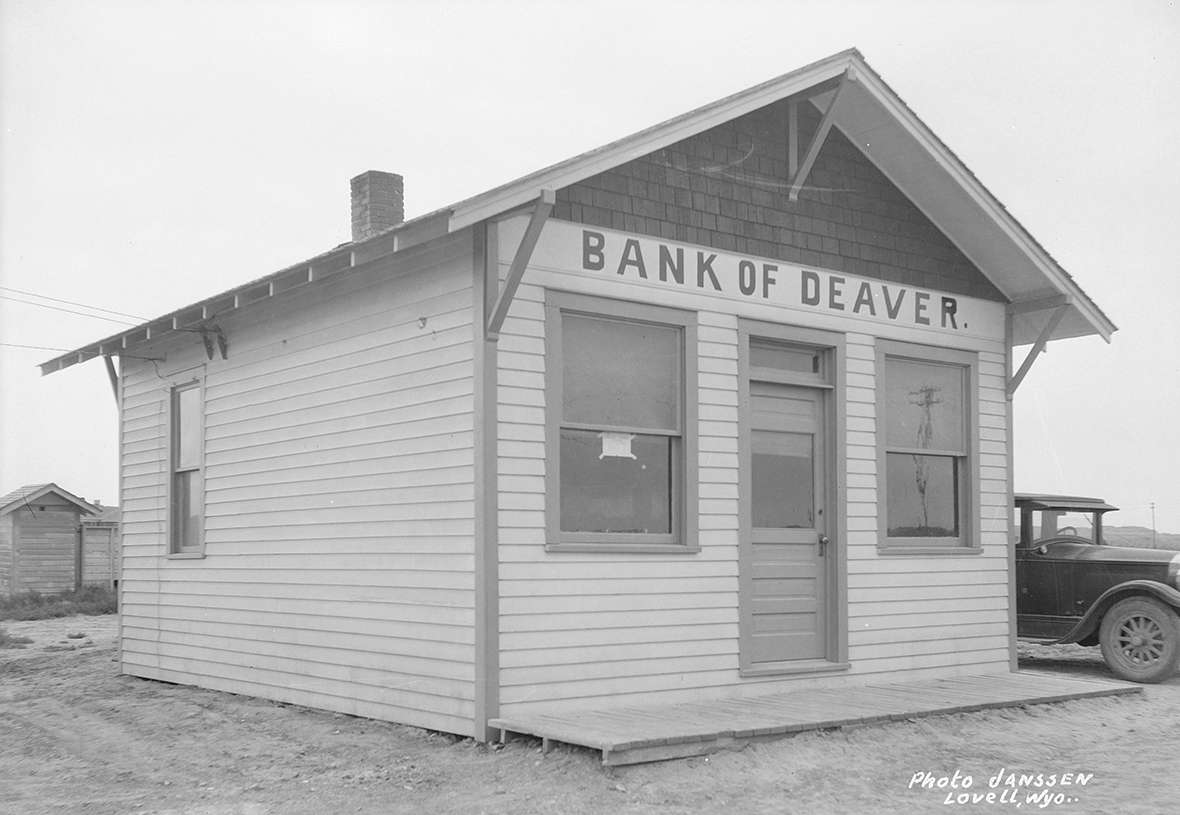

There were only 15 banks in Wyoming when it became a state in 1890. Growth was slow at first. But after 1900, small and tiny towns sprang up as people began to ranch and farm in previously unsettled parts. Few people had cars, however, and roads were terrible.

People who traded at stores in the new tiny towns needed banks, too—so they could borrow money when their farms or ranches needed seed or livestock, and pay it off when they sold their crops or stock each year.

To help out the little towns, the state legislature lowered the minimum startup capital required for a state bank. Tiny banks sprang up in the tiny towns. Sixty new state banks started up between 1900 and 1910, and 22 national ones. In Wyoming by the early 1920s, for example, there were three banks in Lusk, three in Rock River, two in Manville, and one each in Keeline and Van Tassell.

Growing network of loans

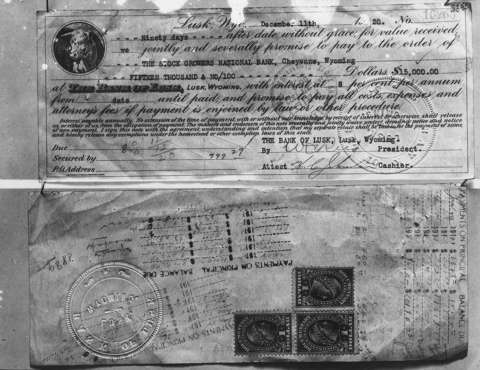

Many of these banks did business with each other—the larger banks backing loans made by the smaller banks in return for a cut of the profits. This allowed the smaller banks to lend more money to more customers. Some Wyoming banks did business with banks much farther away. The brand-new Williams Company Bank of Greybull, for example, had just made some big deposits with the Knickerbocker State Bank of New York, when that bank went broke and started the Panic of 1907.

Banks in Wyoming weathered that storm reasonably well, as their connections with the eastern centers of finance were still rare. Still, people were nervous. Many Wyoming banks kept lots of gold, silver and cash on display for a while to encourage depositors to keep their money in the bank—the same tactic S.A. Nelson would try 17 years later in Powell. It worked. Despite the national emergency, no banks failed in Wyoming in 1907.

The Federal Reserve

Plenty of banks failed elsewhere, however, and in 1913 Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act to make the system more stable and reliable. Banks that chose to become members of the Federal Reserve’s new system could now borrow money from the Reserve when they needed more money to lend out to their customers.

This was similar to the business little banks in Wyoming had been doing with the bigger ones for some years. The local banks used the loans they made to their customers as collateral for the money they borrowed from the Fed. That meant if the banks went under the Fed would take over those loans directly, and so the Fed got a lot more say in the kinds of loans the local Federal Reserve-system banks could make.

There were other rules, too: Member banks had to keep more deposits on hand, relative to the amount of money they were lending out, than they had previously done. The smallest banks had to keep reserves of at least 12 percent of their loan business. The largest member banks had to keep 18 percent. The Federal Reserve System started up in 1916. Wyoming was getting more and more connected to the rest of the banking nation.

World War I and after

Then came World War I, and it must have seemed as if there suddenly was money everywhere. Wheat and cattle prices skyrocketed. Bankers were happy to lend money when farms and ranches had such good prospects.

Not just farmers and ranchers, but speculators, too, borrowed money to buy land, planning to sell it soon for a quick profit. Little banks borrowed more and more money from the bigger banks to keep the engine moving. Everyone’s confidence, in those brief war years of 1917 and 1918, was high.

Then the war ended in November 1918, and the government stopped buying guns, uniforms, trucks, food and fuel to supply its million-man army. Europe, flattened by the war, no longer could afford American wheat and beef. Worse for Wyoming, a terrible drought came in the summer of 1919. The oil business was booming in Wyoming, but farmers struggled to survive.

Many farmers brought in only half the crops they’d harvested in previous years. Ranchers had to sell livestock that their ranges could no longer support. Next came a terrible winter that started in October and ended only in April after the worst blizzard since 1878, killing even more of the livestock that was left.

At the same time, roads had improved, and more people began doing business in the bigger towns. This further hurt the tiny banks in the tiny towns.

Prices fell and kept falling. Steers that had sold for $150 in 1920 went for $65 in 1924. Cows went from $75 to $25, and farmland went from $250 to $75 per acre. This was terrible news not just for farmers and ranchers but for their bankers, too. Loans that had been made with crops, or livestock, or land as collateral suddenly looked far more risky.

If the farmer or rancher could no longer make payments on the loans, the bankers would get the land, instead. But land wouldn’t do the banker much good if it was only worth half or a third the value the banker had counted on when he made the loan.

The Federal Reserve demanded that its member banks make no new loans against ranch land or livestock. In some cases, the Fed even began demanding that its member bankers call in—that is, demand immediate, full payment on—loans they had already made against agricultural collateral.

Many farmers, looking at what their costs would be to start in for another year, and figuring up what their crops would bring at the end of the year and what they would owe the bank, quietly walked away from the land and let the banks have it.

Banks couldn’t sell this land for prices that would pay the debts they, in turn, owed to bigger banks. The bank failures began.

The failures of 1924

When banks failed completely, their depositors lost all their money. When banks were bought or absorbed by other banks, depositors might be safe or partly safe, but loans could easily be called in or cut way back, still ruining even the farmers and ranchers who were keeping up on their loan payments.

In January 1920, there were 153 banks in Wyoming. Four state banks failed that year. Nine failed in 1921. Eight state banks and a national bank failed in Wyoming in 1922, among them Farmers State Bank in Powell—absorbed that year by S.A. Nelson’s competitor, Powell National Bank. In 1923 it was eight and three in each category.

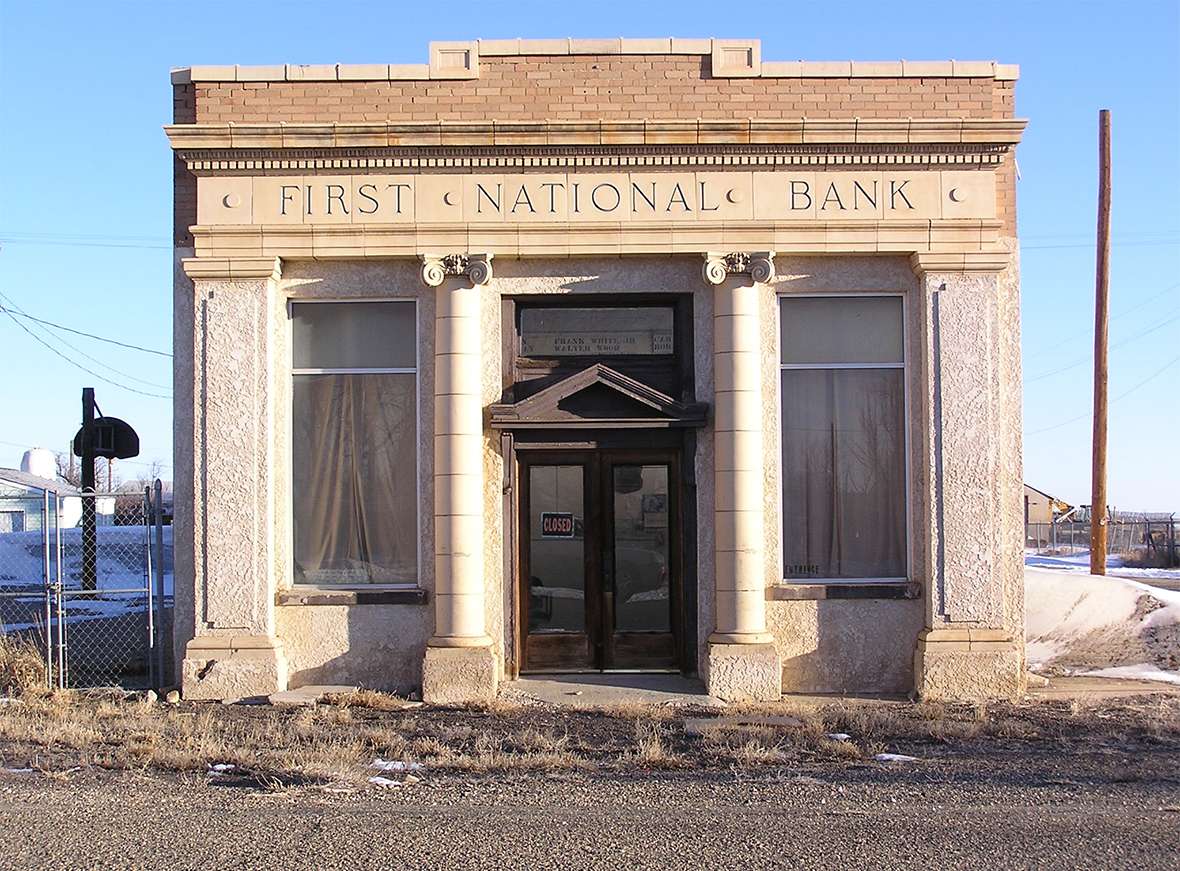

The little banks failed first. But so many were doing business with bigger banks that the bigger banks, too, began to fail. The worst of the whirlwind came in 1924--when 23 state banks failed in Wyoming and 12 national banks. In July, the oldest national bank in the state, First National Bank of Cheyenne, went bankrupt.

A murmuring crowd in Powell

As we have seen, Powell National Bank failed to open on Friday, March 21. Across the street at the First National Bank of Powell, S.A. Nelson and his employees came to work, opened their doors, and waited to see what would happen.

A small crowd gathered on the street outside the bank. Some of the people began coming in to the lobby. The big stacks of cash were plainly visible through the teller windows. People were talking in low tones, unsure what to do. Then Bill Mudgett, part owner of the Home Lumber Company in town, strode through the crowd and made his daily deposit. Another merchant, D.M. Baker, came in, did some business, and walked out again.

On the steps, someone asked him if he’d made a withdrawal. “No, he answered. “I put some in.” This small remark was just enough to strengthen people’s confidence. Depositors who’d been hanging around, reluctant to make a withdrawal themselves but still wanting to be on hand if a run did start, began to drift away.

The first crisis of the day had passed, but still it was touch and go. People wanting to be assured the bank was sound met that afternoon in the basement of the Presbyterian Church. S.A. had opened the bank’s books to a committee that had formed to examine them. An L.R. Ness of the committee reported the bank was sound.

Furthermore, S.A. Nelson had signed all his personal property—his own house, his bank accounts, and various commercial properties he owned in and around Powell—over to the bank, as a way to guarantee his faith to the depositors. This news must have convinced anyone who was still uncertain. The meeting passed a resolution that the bank was safe and sound.

Bad times hang on

Though the bank may have passed through its deepest emergency that day, the bad times hung on—not just in Wyoming but in all the dry Plains states around it. Eastern Montana, the Dakotas and Nebraska were even worse off. Powell National reopened two months later and struggled on for four and a half years before it was sold and became the Park County Bank—which finally was absorbed by Nelson’s First National Bank of Powell in 1932.

First National only barely survived, itself. Family members years later remembered how, for years after 1924, S.A. had to become a farmer, too. Each morning, from sunup until the bank opened, he was out irrigating on one or another of the farms the bank now owned, as its family had abandoned it.

In the evenings, too, month after month, then year after year, S.A. was out on the land, planting, irrigating, harvesting, protecting his depositors by bringing in the crops on the land the bank had never wanted back—crops that, when sold, could pay off the loans the bank had made against them, and keep the bank alive. People in town knew this, and stayed confident the bank would survive.

In Wyoming, there were 153 banks in 1920. Thirty-two new banks would open between 1920 and 1930, but 101 would close. By the end of the decade, only 83 of the soundest, toughest banks were left.

The Great Depression

When, about this time, the hard times that had plagued the high plains throughout the 1920s came to the rest of the nation, the new hard times were called the Great Depression. Twenty-seven more banks would fail in Wyoming in the 1930s.

With all these failures went a great deal of the optimism, the high hopes for a bright future that had drawn men like S.A. Nelson into banking in the first place. Unlike the ways they have since often been shown in books and movies, Wyoming bankers in the early 1900s were businessmen who had staked their hopes, their fortunes and their lives in their own towns.

New land was being settled then. Everything was about the growth that seemed sure to come. This was especially true of towns like Powell, where the newly settled land was irrigated land, made possible by new, government-backed irrigation projects. Irrigation was new to farmers and their bankers, and few had much of an idea how expensive or how reliable a system it was over the long haul.

The hard time stripped the farmers and their bankers of optimism and confidence for many, many years.

As the 1920s moved into the 1930s, bank closures slowed in Wyoming but didn’t stop, and spread to the rest of the country as well. The hard times led voters to throw the Republicans out of Washington. Franklin Roosevelt was elected president, and took office in March 1933.

Roosevelt’s bank holiday

It had seemed as if banks were closing everywhere, and people were panicked about their deposits. Roosevelt declared a bank holiday. All the banks closed for 10 days or so that month, while fears cooled down and a Congress led by Democrats passed a bundle of laws propping up Federal Reserve member banks with new loans and other kinds of security. The nation breathed easier. Withdrawals slowed.

Three months later, Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Banks from then on paid the government what amounted to an insurance premium of half of one percent of all their deposits. These funds, combined with others, provided enough to insure depositors that any accounts up to $2,500 would be protected if a bank failed. That ceiling was raised to $5,000 in 1935, and to higher levels in later years as the century rolled along.

Depositors, at least, were safe, and confidence slowly began to return.

Resources

- Huntoon, Peter W. “National Bank Failures in Wyoming, 1924.” Annals of Wyoming Vol. 54 No. 2, spring 1982, pp. 34-44. Accessed Sept. 6, 2017 at https://archive.org/stream/annalsofwyom54121982wyom#page/34/mode/2up.

- Koelling, Robert. First National Bank of Powell: The History of a Bank, a Community, and a Family. Powell, Wyoming: First National Bank of Powell, 1997. Rich in anecdotes, starting with the March day in 1924 when the First National barely escaped a run on the bank, the book includes a good bibliography on Wyoming banking, and includes a clear, vivid narrative of the 1939 jailbreak, flight, and final death of Earl Durand, in a hail of bullets in front of the First National Bank of Powell.

- Larson, T.A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965, 412-417.

- Roberts, Phil. New History of Wyoming, Chapter 14: Wyoming in the 1920s. Accessed Sept. 6, 2017 at http://www.uwyo.edu/robertshistory/new_history_of_wyoming_chapter_14.htm.

- Woods, L. Milton. Sometimes the Books Froze: Wyoming’s Economy and its Banks. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985. A detailed history of Wyoming banking.

Illustrations

- The photo of Powell and its First National Bank is from the Park County Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The Wyoming National Bank postcard, the image of the Bank of Lusk note and the 1907 photo of the bank in Greybull are from the Wyoming State Archives. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the Bank of Deaver is from the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Used with permission and thanks.

- The photo of the First National Bank in Rock River was taken in 2011 by the author. For details on the bank’s failure at a time when its officers were looting local town and school board funds to keep the bank afloat, see Wyoming Tales and Trails, http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/lincrockriv.html.